| Date interviewed | 1 March 2018 |

| Date newsletter posted | 9 March 2018 |

| Farmer | Sivion Mbili |

| Farm | Juluku |

| Area | Harding |

| Mill | Umzimkulu |

| Area under cane | 420 hectares |

| Other crops | 70 hectares of timber (gum and wattle) |

| Cutting cycle | 18 – 20 months |

| Av Yield | 89 – 90 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 12 – 14,5% |

| Best Yield | 98 tonnes per hectare |

| Best RV | 16% |

| Varieties | N12, N38 |

I had just been creating the Top Farmer Trophy, or should I say the “Great” Farmer trophy (the last newsletter would have given you background on this change) and, on the reverse of it, I have given a snippet of wisdom from each of the 2016 Top Farmers interviewed, alongside a photo of them. Seeing them all on one page, I realised how “pale” it was No farmers of colour were interviewed last year, unless you are counting the really tanned ones … so, you can imagine my excitement when Sivion Mbili confirmed that he would allow me to interview him this year. Sivion is based in Harding and the Umzimkulu board put his name forward, with this recommendation: “You are going to love the interview with Sivion. He is humble, yet a dynamic entrepreneur. He has come so far and has made such a wonderful success as a black farmer without government assistance. He is a perfect example of what is possible through hard work and perseverance. We look forward to reading Sivion’s story.” As I found out, that statement could not have been more accurate.

Sivion is a true ‘emerging farmer’ – he struggles every day to keep his head above water and swim on towards the goal. For him, that personal goal is 15 000 tonnes per annum. At that point, he feels he can hire the staff and purchase the equipment he needs to run this enterprise successfully. Right now, he feels very far away from that but is encouraged when he looks back to last season where he delivered 9 000 tonnes and this recent season, he expects to have been 11 000 tonnes. So, if he stays on track, the end of the 2019 season should see him make landfall!

History

We settled into a beautiful lapa in Sivion’s garden, surrounded by the healthy sound of buzzing, swarming bees, and began exploring what lead to him being where he is now.

He used to be a city-based businessman, owning and running butcheries and bottle stores in Durban. As chain stores crept into the city centre, Sivion grew more concerned about his shrinking turnover and decided to explore rural options, starting with the 40 hectares of grazing land his father owned out here, in Harding. He contracted a local farmer to plant part of it up to sugar cane and then made the career move to farming completely in 1999. He soon planted the balance of the farm with sugar and timber. Enthusiastic and energised by the farming experience, Sivion purchased a large farm in another area, using a 100% bank loan plus another loan which he used to develop the crop. He soon learnt that financing a farming operation on this scale was not feasible. The repayments and low sugar price (only R120 per tonne at the time) sunk the operation. He moved back to Juluku and focused his efforts here.

The lesson he took from this early failure was to slow down rather than give up. He had fallen in love with farming and dedicated himself to making a success of the career. He slowly started buying up or leasing available land around him. The first opportunity presented itself through the local church, who offered him 180 hectares. Luckily for Sivion, the government launched the LRAD (Land Reform and Distribution) scheme at the same time. This loan enabled him to purchase the land but he still faced huge development costs. These were met through a loan from Land Bank and he planted all 180 hectares to sugar cane.

A little while later, another 200 hectares became available from the same church, but this time, it was in the form of a lease. He grabbed the offer but was not sure how he was going to finance the crop establishment; the Land Bank loan route was just too expensive.

Some of the leased land developed by Sivion.

Some of the leased land developed by Sivion.

It was at this point that the Illovo Scheme came along. Sivion is so grateful for this and says, “It gave me wings.” Illovo’s cane area expansion programme is opoen to all qualifying farmers (supplying an Illovo mill).

It was at this point that the Illovo Scheme came along. Sivion is so grateful for this and says, “It gave me wings.” Illovo’s cane area expansion programme is open to all qualifying farmers (supplying an Illovo mill). Illovo partners with farmers by assisting with working capital – in Sivion’s case it was for the development of 100 hectares over two years. Illovo recoups the development costs when the expansion-cane is delivered. The assistance scheme is structured in a way that makes it feasible for farmers to manage the financial burden of growing their cane enterprise and Illovo’s field officers support the execution of the development, also releasing progress payments on what is successfully achieved.

Some of the lands Illovo Scheme has helped Sivion develop.

Some of the lands Illovo Scheme has helped Sivion develop.

Then, last year, more community land became available to lease – 150 hectares this time. Sivion always encourages the community to make the best use of their land in this way. He signs a 10-year lease with them, giving him a fair chance to recover investment but also allowing them flexibility to use the land for other purposes if they’re not happy with the arrangement. Illovo Scheme has also helped with the establishment of this land.

Sivion emphasises that he would never be on track to achieving his goals without the help of so many people around him, “It’s just impossible to do it alone.” And so, he does his best to give back and is currently assisting an emerging farmer neighbour; Mbotho. He is cutting his teeth with 15 hectares but Sivion is encouraging him to take on more as he sees the enthusiasm and success Mbotho is showing with his current farm. Sivion is so grateful to his neighbours who have helped him out of many tough situations and give him guidance whenever he asks. Sivion’s dad was also a butcher so he did not get any farming “inheritance” from him. His children are not involved, so farming would be a very lonely experience without these gracious neighbours.

Sivion has two children; a son and a daughter. Sadly, his son has chosen to work in Durban rather than join him on the farm. His daughter studying Chemical Engineering and he encourages her in this ambitious course.

“Farming is the hardest work you can choose,” Sivion says, “Retail was easy. Farming is physically and mentally and financially draining. I run all day, trying to meet all the needs of my business. At night, I worry about how to cover all the costs and how to afford new equipment.” But, at 54, Sivion is determined and focused, and constantly hunting ways to keep growing his farming enterprise.

Hunting

Sivion uses all his business acumen to fuel the journey towards his goal. While driving around his farms, we saw evidence of all his schemes – he calls it ‘hunting’ … “I must go out and hunt ways to pay the bills of the farm, so that I can make it to my goal and then focus on the farm alone. This is a hard time but I enjoy it and keep focused on the goal.”

Among Sivion’s ‘support businesses’ are: timber plantations, an entertainment centre (with Zulu dancing), guest house and wedding venue, charcoal manufacturing and packaging facility and timber and cane harvesting services. But he has been known to do anything to put bread on the table, including selling bags of fire wood in town, and taking loans from the local stokvels (run by his own labour). Of all the farmers I have met thus far, I believe Sivion has done the most with the least in order to achieve what he has today. There’s a passion in his eyes that lights up the determination burning within – he has faced worse lows than most and I hope he is rewarded with greater highs as a result.

Gum tree plantation

Gum tree plantation

Entertainment Centre, Guest House

Entertainment Centre, Guest House

Timber harvesting

Timber harvesting

Wedding venue

Wedding venue

Farming advice

The obligation to bring you something innovative and pioneering in every farmer profile encourages me to dig around to find what Sivion does that you can emulate and thereby contribute to your own success. But, despite how much I dig, I am forced to accept that, sometimes, there are no “hidden secrets” – sometimes it is just a combination of doing everything well, with passion and enthusiasm while keeping your eye on the goal.

Drought: “This was an incredibly bad experience,” says Sivion, “yields dropped to 45 tonnes per hectare. We were losing badly.” He attributes his survival through this period to the variety he favours – N12.

Ripening: This is something he experimented with a little last season (2016), on 20 hectares. The result was around a 1% increase in RV. He hasn’t tried it again since then and believes that the 20-month growing cycle he aims for yields sufficient RV.

Pesticides: Eldana had never been a problem before this year, when he received his first recommendation from the inspectors to cut a field. He’s not sure of the reason behind this new problem but we discussed many possible causes and he agreed that poor cutting (leaving stalks too high) might be partly to blame. Last season, Sivion offered his cousin an employment opportunity on the farm and tasked him with managing the cutters. He explained how that had not worked out. One of the issues was cutters leaving high stumps. I mentioned how I had learnt from another farmer that this could promote an Eldana problem as the worms stay burrowed in this stump, ready for the next crop. “Aha, perhaps that is it,” says an interested Sivion, “I am glad I have decided to take back this part of the management.”

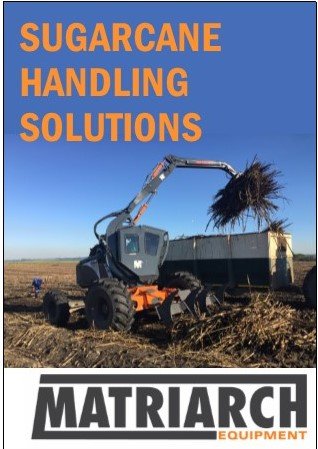

Harvesting: Sivion uses a cut and stack method. Side-loading trailers transport the bundles to the zone, where they are weighed and loaded into contractor’s trucks, using the crane. Cutters are paid per tonne. Juluku is about 75kms from the Umzimkulu mill.

Straight after a harvest, Sivion sprays the field with herbicide and then contracts LNT (Liquid Nutrient Technologies) to apply the fertiliser. He acknowledges that this appears expensive initially but, when he considers the inaccuracies of manual application of granular fertilisers as well as the cost of theft, he is more than happy to pay LNT. They test the soils and tailor the application accordingly.

Then, when the crop is about a metre tall, he sends hand-weeders in to clear the fields. From there on, the crop is left until it reaches 18 to 20 months.

Labour: Being so close to the location, Sivion feels constant pressure to provide employment, which he does whenever he can. It is one of his highest cost centres. He prefers women to men, saying that they are hard-working, loyal, consistent and less prone to drinking and striking. When there is an issue, they talk more freely and participate in healthy negotiations. He laughs and expresses his wish that they were strong enough to cut the cane as well. Sivion explains how valuable it is to make his employees feel as though they are part of the business so that they work hard even when he is not watching. He interacts freely and injects lots of laughter and comradery into the relationships with his workers, constantly emphasising that, without their dedication, the farm will fail.

Admin, staff and technology: I was stunned to learn that Sivion runs this business without any admin support. He doesn’t even own a computer (or a smart phone) or have an email facility. If he achieves so much without these ‘vital’ tools, imagine what he could do with them! He explains his challenge: to increase turnover (and achieve my goal) I must increase capacity. To increase capacity, I need to hire support staff but I need money (through increased turnover) to be able to afford the staff. Sivion finds himself in a classic Catch22. But, true to his spirit, he won’t languish in this hole for long, in fact he has already hired a lady to assist him with administration. Undoubtedly, this will mean he has to “hunt” more but hopefully she’ll add value and increase his capacity to grow the income and thereby be able to employ someone who can help with the running around to punctures, breakdowns and calls for diesel, further growing his capacity to increase turnover.

Another job on the To Do list …

Another job on the To Do list …

Secrets for success:

Sivion believes he will succeed because of his focus on growth. He emphasises how essential it is to push through the pain of the process. “There can be no rest until you get to the goal. But, I love farming, and I love to see growth in nature too, whether it is trees or sugarcane. I don’t like to fail. I will keep on pushing, rain or shine. To give up is unacceptable.” When doors close, Sivion just looks for the next door. This was illustrated in a scenario that has unfolded over the last few years: 80 hectares of the land he leased from the church, and had planted to sugar cane, was claimed by one of the communities. He had borrowed money from Land Bank to develop this land but willingly accepted the claim and subsequent pay out that the government made to compensate him for the expenses he had incurred in cropping the land. The land was handed over to the community with Sivion’s offer of help in keeping the sugar cane going. He harvested their crop for them and explained that they need to reserve some of the income for spraying and fertilising. Instead, they distributed the entire income and now, the land has gone wild. No farming has been practiced here and he is currently negotiating with them to lease the land from them and replant it. This, he hopes to achieve in the next two years.

The land claimed by the community has gone wild.

The land claimed by the community has gone wild.

And then we dared to talk soft politics and why, on the whole, the current land redistribution programme is failing on an agricultural level:

- We concurred that the ‘group’ factor is largely to blame. Whenever something is handed to a group, who is actually responsible? Who is going to stand up and do the hard work that everyone will benefit from, and how long will it take for that person to tire of being the only worker. No, group claims are not feasible.

- We also discussed the claiming of established farming operations by subsistence farmers. Sivion’s analogy of taking a Spaza Shop owner and expecting him to run Pick ‘n Pay successfully was helpful. So, unequipped claims are not feasible either.

- We also questioned the logic of taking a successful farming operation away from the farmer who made it successful – surely that was a good situation to leave as is – in great working order. We can therefore add Unwise to our list of unfeasible claims.

- Unsupported claims are also not feasible – you cannot just hand land (good or bad, equipped or unequipped, wise or unwise) over to someone and expect anything but failure. Everyone in this situation will need financial and advisory support initially. Sivion illustrates this by pointing to a large timber farm on the horizon, “That’s a great farm. It is well-equipped and successful. It’s perfect. But, if you gave that to someone today without advice and finances to get through the first harvest at least, they would ruin it. You need money to be able to harvest. You need knowledge to market the harvest. No one can do it without support.”

- Uncompensated claims are also unacceptable in Sivion’s opinion. He has no idea how his father came to own the piece of land he now calls home and if that (with all its improvements) were to be taken without compensation, he’d be very unhappy. “It’s just unfair and cannot be the solution.”

So, enough about what WON’T work, we moved on to what WOULD work … redistribute land that is NOT already being used optimally. Give it to individuals who WANT to farm and equip them financially. Give them guidance and instruction. Yes, yes … we know it’s not that simple but we will leave the details for another day.

Sivion’s advice for other emerging farmers:

- Before committing, understand that farming is a long-term investment. The expenses will always exceed the income until the operation reaches an economic scale. Sivion is living in this stage of his enterprise now and gives a very real example: his timber farm, which will only be ready to harvest in 5 years, consumes R20 000 in wages alone, every week. He looks at this as his “investment”. He cannot neglect the farm maintenance however difficult it is to find that R20 000 every week. Fire breaks have to be cut, weeds have to be pulled. Every day is a fight to keep the operation alive.

- Farming is different from all other careers in that it takes so much money before it gives anything back. Even if you are given an established harvest-ready farm, you still have to invest in the harvest (fuel, labour, equipment) and then wait for 30 or 60 days to be paid. It’s hard – do not expect to get any money in before giving a whole lot out.

- You HAVE to manage cash flow carefully. Always have an alternate plan of how you will pay the next bill because it won’t be from farming income.

And that wraps up my time with Sivion. I am honoured to have spent this time with a man who has few hours to spare. I leave filled with respect for this hard-working, passionate man who has his eyes so securely set on the goal he has set for himself.