Yes, it’s been 5 months since I last posted a story! Feels like years.

I’m really sorry to have made the break half way through a JAFF’s story but it wasn’t planned …

I’m quite sure a refresher is in order so please remind yourself of the JAFF context with a quick review of Part One.

And then it’ll be time to jump straight into the sequel …

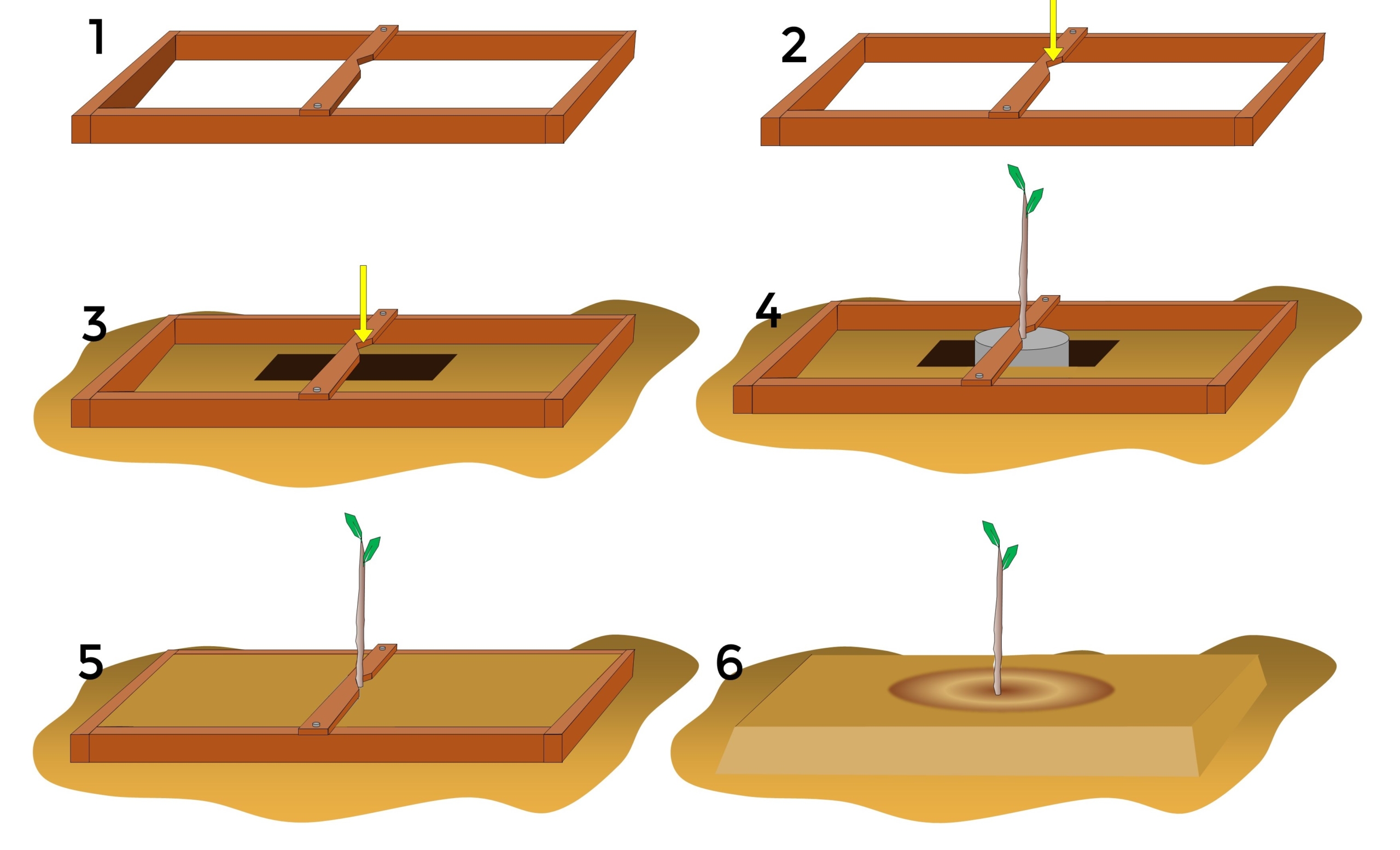

PLANTING PROCESS

JAFF uses a planting frame to make sure that trees are never planted too deep. This is one of the greatest risks to new trees.

1 – Make a 1m x 1m frame from 75mm x 50mm planks with a plank bolted onto the top. This plank has a notch in the centre.

2 – Place so that the planting marker is centred.

3 – Dig your normal square hole (spade size)

4 – Place the tree in the hole so that the top of the soil touches the underside of the cross-plank. i.e.: 75mm above ground level.

5 – Fill up around the roots and up to the top of the bag soil using 50% soil from the ridge & 50% compost and 150g 2:3:2 (16) organic fertiliser.

6 – Remove the frame and create a well around the base of the tree. Fill this with 20 litres of water (if necessary) Put 60 litres wood chips in the well.

NB: Nothing must touch the stem of the tree.

“Even 1cm too deep increases mortality tenfold,” warns JAFF, “by planting 75mm above soil level it gives room for the trees to subside as the soil settles but they won’t go too deep.”

I asked about using the planting tool when there’s a pre-established cover crop in the way. JAFF says, “It’s not easy.”

Watering depends on the rain; if it’s too wet, they won’t add additional water. Fertiliser is added to encourage roots to move out from the ‘bag zone’.

Stems have already been painted in the nursery. JAFF uses ‘Orchard paint’ which he says is a lot cheaper than PVA. “It costs R400 per 20l but you get 80 litres out of it,” says JAFF, “The cheapest PVA is R220 for 20l and it’s so thin you can barely stretch it without compromising efficacy!” The Orchard paint is applied with a paint brush. A leaf spray, to screen the young leaves, is also applied in the nursery.

In terms of timing, JAFF starts planting when he’s sure the risk of frost is past and makes sure it’s all done before Feb. As a guideline, JAFF advises that, if you are not going to get some growth after planting them out then rather keep them in the nursery. He has planted in Jan and also in Sept of the same year and now these trees are the same size so it’s not worth the ‘risks of winter’ for these young trees. This was evidenced when some orchards JAFF’s caring for were planted out in March and there were unacceptable mortalities coming out of winter. He says it’s preferable to deal with the heat of summer, when there is rain, rather than the cold of winter.

JAFF stakes the trees once they’re safely in the ground using a figure of 8 knot tied to a stake that is placed at an angle facing into the wind. He prefers a tighter knot so that there is less friction and rubbing.

“Oh, and this is important,” remembers JAFF, “never leave the trees in the sun while you’re planting. Pre-dig the holes while the trees are waiting in the cool nursery, then take trees out and place them in the holes and cover up as soon as possible. This can make a massive difference in mortality.”

IRRIGATION

Once the small trees are in, it’s time to add water … here, dryland orchards are watered by hand – a tractor cart and 2 people, each with a hose. The first person applies 10l per tree and the second comes behind, adding another 10l, which gives the first 10l time to soak in. Making a little moat/well around the base of the tree certainly helps with placement.

JAFF has chosen to farm mostly dryland on this farm and on the new plantings. This makes cover crops, mulching and soil health even more vital.

When I opened the discussion on irrigation and asked JAFF what input he had he scowled and said, “Irrigation rhymes with irritation.” So, clearly, it’s not his favourite part of farming. He confesses to not being a good irrigator – but that he would like to improve. To compensate, he focuses instead on soil health and organic matter. He must be doing something right as the yields off unirrigated orchards are impressive; 7t/ha in an ‘off year’ and 20t/ha in an ‘on year’.

Dryland farming avos is certainly feasible; there’s really just one critical period that could benefit from supplementation; “It’s just the end of winter that’s a challenge, if there’s no cold front to bring a little bit of rain before flowering, that could affect the load the trees will set up to carry.” He added that increased organic matter in the soil would serve as a buffer if this rainfall was low and it’s why he’s working so hard to improve soil health across the board.

PRUNING

JAFF starts on this, in about year 2, with some basic shaping. He says it’s worth starting early so that you keep the canopy open. “Some farmers like an open bowl shape,” says JAFF, “but, if your farm is prone to frost, the bowl will be open to frost damage.” So, although he prefers this shape, he opts instead for a more Christmas tree shape so that his canopies retain some heat inside during cold snaps. After winter JAFF prunes back a large limb so that internal growth is stimulated.

“If you’re going to choose only one thing to be good at in avo farming, pruning has to be it,” says JAFF, “You can reduce disease and the amount of spraying by pruning well.” He adds that harvesting costs and risks are also contained when you have well-shaped and controlled trees.

In terms of height, JAFF keeps his trees to 70% of the interrow which is about 4 to 5m at most.

“The primary purpose of pruning is to let sunlight in,” says JAFF, “and avos love to be pruned – they bounce back and it keeps their vigour up.”

All the pruned material is incorporated back into the orchard as mulch. JAFF has a team of 3 on chipping prunings. He runs a 35kW tractor with a chipper; one guy walks in front, placing the branches in front of chipper. The tractor driver and one other guy feed the chipper. “It takes them 2 days per hectare,” says JAFF.

A wood chip pile that wasn’t as spread as it should be. The roots are enjoying it though.

JAFF says his electric pole pruner is the best tool they have on the farm. This electric one allows them to talk whereas the petrol powered one would drown out any conversations and instructions. They discuss a few trees together, while the pruning man marks the branches then, when they’ve gone through a few trees as examples, he goes back and cuts the orchard.

JAFF does this at the beginning of each orchard block. They then do another follow up prune 3 months later. This follow up is vital if you’ve done a big prune; sorting out the witches brooms will be key in the long term outcome. “Good farmers will prune 3 x per year,” says JAFF, “with the major one being finished by December so that the tree can take this load reduction into account before it does the second load drop in Feb.” JAFF then adds, with a smile, “This is ideal but not always attainable.” Similar to macs, the first crop adjustment/load drop is in November.

When it comes to pruning off flowers, JAFF believes that you should prioritise pruning the RIGHT branch, regardless of how many flowers it has on it. It’s a very ‘farmer’ thing to do to avoid the branches with lots of flowers on, for fear of compromising yield. “I do this too often and, every time, I regret it – making good choices in pruning is often not as easy as you’d think.”

I do believe there’s a silver lining to every cloud, however ‘out of sight’ it may be, and was happy to hear that wind helps to prune the trees, in fact, “It can compromise their growth by up to 50%,” says JAFF. Okay – maybe that’s a bit much.

JAFF does not skirt any of the trees, apart from what the slasher does. If a low branch has a lot of fruit, they will place supports underneath the branch for the season and consider whether it requires pruning after harvest.

Oldest trees – well pruned to allow maximum sunlight and spray penetration. 10m x 10m spacing.

Support for a heavy branch. Once harvested, branches like this will usually be pruned off to make way for new, stronger branches BUT events like hail (and the consequences for yield and income) impact your pruning decisions.

JAFF explains that a general rule of thumb for pruning is that you should be able to see a person though the tree but not be able to see who it is.

JAFF says the tractor does fit down the row in this healthy-looking Hass orchard.

REDIRECTING RATHER THAN PRUNING

JAFF wanted to increase the canopy area quickly in a particular orchard so, he ‘opened windows’ by manipulating branches instead of cutting them. He used 50cm-long pieces of gum pole as weights. Was it successful? “The weights worked. The canopies were opened without pruning but I’m not sure whether there was a financial benefit,” admits JAFF, “did it increase yield or decrease costs? I’m not sure.”

I found a remnant of the ‘canopy opening without pruning’ project still hanging on a branch in this orchard.

POLLINATION

Although JAFF doesn’t prioritise cross pollination and most of his orchards are pure blocks they do border other varieties. While discussing this topic, JAFF mentioned that they have their own beehives, randomly placed all over the farm. He prefers to place these away from the orchards so that the bees have to fly TO the orchards. He believes that this placement broadens their work area. If bees are placed IN the orchard, they tend to stick to the row they’re in. Mmmm.

They have about 3 hives per hectare right now and, to roll this rate out through the new developments will require 600 hives alone. A daunting task. And JAFF warns that beekeeping is a very intricate and complicated business; it’s vital to make sure that they’re fed and cared for. It’s also important to know that avo pollen and nectar is not a bee’s first choice; they’ll choose a blackjack flower over an avo flower. JAFF encourages his bees to actively participate in pollinating the avos by bringing them a little closer to the avos when the flowering is about 10%. He also mows the weeds down at this time; effectively mowing down the competition. “Please remember that bees suffer when moved,” warns JAFF, “so do it responsibly and cautiously, if at all. The transport, handling and relocation process will always result in significant losses to the hive.”

Bee catch boxes – they’ve been brought here from other farms where the swarms were caught – they now need to be relocated into bigger hive boxes.

NUTRITION

JAFF has a different approach to nutrition and, to understand it, we need to consider his context; the area they’re farming in has predominantly been timber and sugar cane. It is only recently that avos have started growing (‘squse the pun ) in popularity. So, the support services are not yet well-equipped to advise on avos. JAFF realised his needs were not being met when he submitted soil and leaf samples. His expectation was a precision (per field) programme in return. Instead he received a generic plan across all green skin and dark skin orchards, regardless of the differences in soil and trees in those orchards.

His ingenuity was sparked. This, together with the fact that he doesn’t have a farming background, and therefore no preconceived ideas, traditions or previous generation views (which often tend to be rather pro-chemical), sent him into ‘discovery mode’ …

PATH WALKING

JAFF considered nutrition through a fresh lens. He considered the farm (soils, location, weather etc) and mined information online. He felt most aligned with the regenerative, organic approach which made sense, given his background in conservation.

“This route is not an easy road,” shares JAFF, “it’s already been a LONG journey and there’s still so much to learn.”

A big piece that JAFF builds into his programme is harvest take-off. Avos are big users of potassium and so it’s important to know how much to replace. He uses yield forecasts to calculate this. Eg: a 30t/ha crop will require a very different amount of potassium than 4t/ha crop would.

Another interesting question was, “If you are loading your soils with organic matter do you even need to supplement with additional nitrogen?” Trying to find an agronomist aligned to this way of thinking has been a struggle and most commercial ‘organic’ solutions are very expensive. JAFF has also struggled with matching or understanding the results of soil and leaf analyses together. eg: the soil can be full of zinc yet there is no zinc in the leaves; they’re literally dying for it. Trying to understanding what happens INSIDE the soil (eg: aluminium suppressing the uptake of zinc) and INSIDE the plant and how that can be evidenced in lab results is JAFF’s biggest challenge.

LIEBIG’S LAW OF MINIMUMS

When I discover gems like this I often feel like the last one to the party but I know there are at least a few of you who will also find this law, that has helped JAFF through many puzzles, enlightening … Basically, the overall growth/yield/quality will be limited by the least available element. So, applying more of anything else will be wasteful. Only once you have dealt with the lowest available resource; will you ‘level up’. And then, another element will become the lowest and require attention before the ‘next level’ is unlocked.

The law is well-illustrated with a barrel where water = potential (yield) and the slats = resources (nutrients).

The theory/law works on the principle that, until ‘slat 1’ is dealt with, supplementation/tweaking of ‘slat 2’ will be fruitless as the water is always going to leak out of the gap above slat 1, even when slat 2 is the perfect height.

The catch is trying to figure out what ‘slat 1’ is! But – the concept is sound and can be applied in cautioning farmers against blanket, generalised, non-specific fertiliser programmes and to rather ascertain exactly what each field (or tree) is lacking and attend to that. This will be key in maintaining a healthy tree that is able to utilise all the nutrients supplied to it.

JAFF says that another key to optimising nutrition is to align tree phenology and application, “the difference between a really good fertiliser programme and a really bad one is 2 weeks.” JAFF adds that he always seems to be late but is determined to improve! Complicating this timing is that 2 sides of one tree can be at different phenological stages. I’ve seen this myself!

WOULD HE EVER CONSIDER GOING COMPLETELY NATURAL i.e.: NO ‘BOUGHT’ FERTILISER?

“I’m not sure that’s possible with avos,” ponders JAFF. He draws on podcasts (his ‘university’) and enjoys John Kempf, an Amish farmer, as well as Graeme Sait, an Australian. The main thing he’s learnt from them is that turning to regenerative farming is a gradual process. JAFF has reduced their nitrogen supplementation by 40%; “we probably don’t need any anymore but, I’m nervous.”

He’s always on the lookout for ‘organic’ substitutes and, last year, he found a nice one; “Remember when the potassium sulphate price went up to R21k/t? I was desperate for options as we were anticipating high yields (it was an ‘ON’ year) and needed a LOT of potassium to supplement recovery. I found a distillery waste product which is 1,2% potassium and that’s worked well.”

Apparently sugarcane farmers use it a lot; spiked with KCl. JAFF says avos are ‘allergic’ to chlorine and it sanitises your biome-world so he’s not using the ‘spiked’ product. The product is liquid; the formula is 0.3%N, 0.03%P, 1.2%K which suited JAFF’s suggested programme perfectly and it’s 60% cheaper than the chemical fert equivalent. It’s applied with a tractor and a water cart with sprayers. A visiting industry expert said, of the orchards where JAFF used this product, “these are the healthiest trees I’ve seen carrying this much fruit”. It was remarkable … until they were hit by hail 2 weeks later.

ONGOING ADJUSTMENTS

Ahead of the season JAFF forecasts what he anticipates getting from each orchard and breaks that down into a lugs -per-tree number. The indunas keep him informed of what they see happening on the trees and they adjust nutrition accordingly eg: if the forecast is 5 lugs per tree and the induna says he’s seeing 6 then the programme is adjusted slightly.

Sick looking trees also get a dose of MAP. And JAFF adds 3 tonnes of homemade compost per hectare, across the board.

HOMEMADE COMPOST ON A NEW LEVEL

Settle in – this part is good!

JAFF makes his own compost and compost tea. Two separate products. The compost is fairly simple; kraal manure (which he gets, for free, from the local feedlot in Dec) and sawdust/wood chips. He then uses heat to mature the pile (thermal composting) by getting the temperature up to 60°C. Once there, he leaves it for 3 days and then turns the pile with a TLB. This heating and turning is done about 3 times. After that, the pile settles and is only tuned once a month for about the next 5 to 6 months, after which it is ready to be applied. JAFF does this in early Spring, every year.

Saw dust and kraal manure breaking down well. JAFF says you need to get the ratios right; sawdust has carbon to nitrogen ratio of 500:1. Kraal manure is 1:30. The N balance should be 70:30 (carbon:nitrogen). This is necessary to get the thermal heat going that will catalyse the breakdown.

Some healthy fungi growing in the compost heap.

JAFF worries about using kraal manure because of the chemicals and additives the feedlot cattle are given eg: deworming medication etc. But he needs 100 tonnes of manure and where can he get this without it being contaminated? JAFF hopes that the process of thermal composting will kill some of the baddies. JAFF does get the manure analysed so that he knows what it is contributing to the soil but hasn’t tested for glysophate (read this to see why that’s important: https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/1374-2/ ). Another mitigating factor is that his application rate is low – 3 tonnes per hectare.

Being in a timber area, JAFF wonders whether the forest waste couldn’t be used.

And then there’s the compost tea … not so simple … it’s quite literally brewed!

REQUIREMENTS:

- Vermicast (aka worm poo)

- 20kg of diverse organic matter (JAFF includes horse manure, geese droppings, wood chips, cabbage leaves – anything; the more diverse, the better – but pay attention to achieving a good balance of C:N)

- Fish hydrolysate – can be defined as proteins that are chemically or enzymatically broken down to peptides of varying sizes.

- fish (heads, bones, skins and guts).

- Sugar and water.

- Braciousis vinegar (sauerkraut juice) – 200ml per 20l bucket – a great bacteria and fungi feed.

This mix is ready when the pH is 4.6 and the smell becomes like a sweet, rotten citrus smell. It also bubbles – if you put a pipe in, and place the other end in a glass jar filled with water you will see the bubbles come through as the proteins break up.

- Molasses

- Sea kelp – JAFF uses the cheapest one he can find.

INSTRUCTIONS: All this goes into a big JoJo tank, fitted with an aerator, and bubbles for 24 to 48 hours.

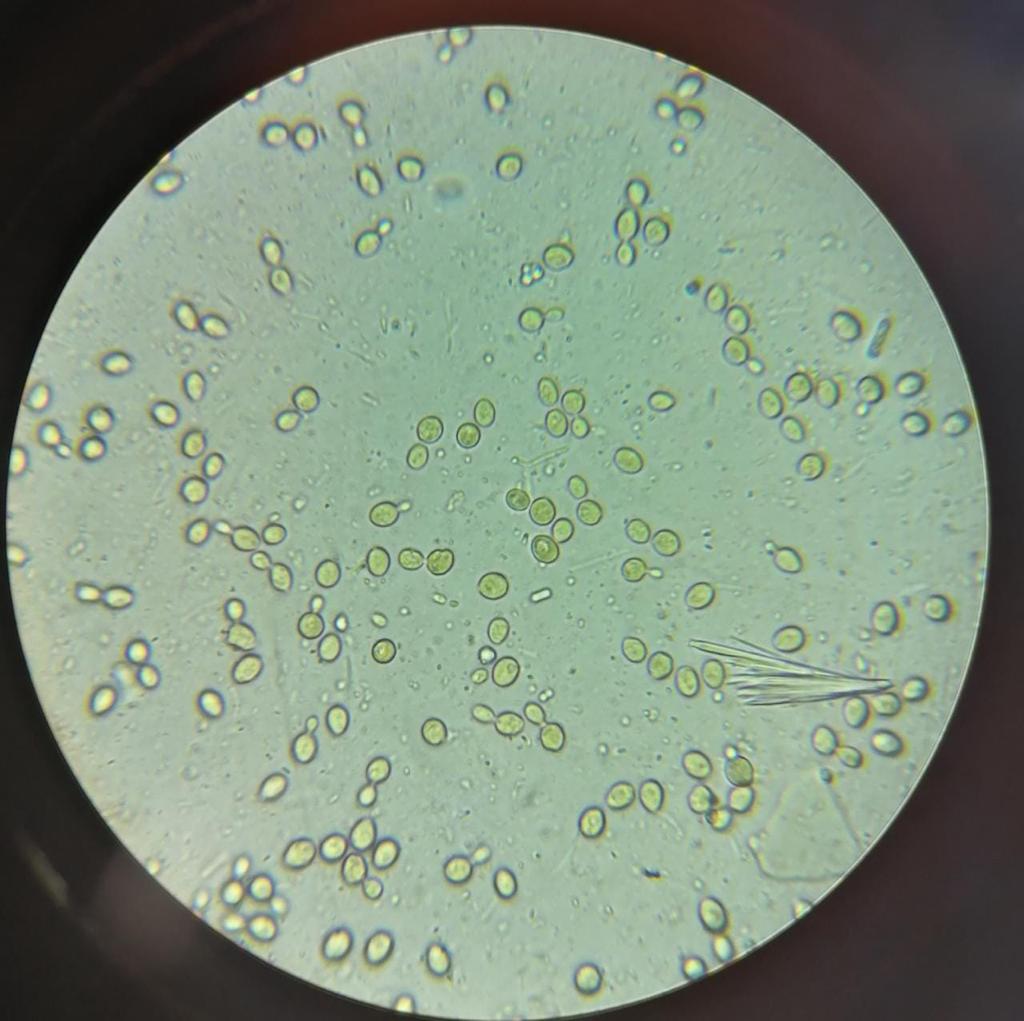

During this phase, JAFF uses his microscope to check for life – he wants LOTS; good compost requires effort and life. He mixes 1 drop of tea with 10ml water and uses 1 drop of that diluted mix on the slide. “YouTube has taught me what I’m seeing and it’s incredible; there are nematodes, bacteria, fungi, Protozoa eating bacteria – it’s a zoo!”

JAFF has a microscope and checks his compost tea for life before using it.

JAFF also measures the temperature to ascertain life – if it is there the temperature will rise slightly.

If JAFF has any Trichoderma then he adds this to the tea as well. On this topic, he shares an interesting thought; “I’m not sure why the industry has become fixated on this one specific fungal species when there are endless species out there.” He would like to get as many of these into the soil as possible.

So – does this compost tea work? “I believe it does but haven’t kept a control line so there’s no proof.”

The next step is to add a carbon source, like biochar. “I’m just concerned about whether this will warp the soil test results by over-inflating the organic content readings,” shares JAFF. JAFF uses these results to ascertain his carbon footprint; right now he’s so far ahead (negative carbon footprint) that he’s questioning the numbers).

The tea is applied at the same time as the distillery waste product. (2000l/ha liquid distillery waste + 200l/ha tea)

Water in the grey aeration tank (tea pot) is topped up from green Jojo tank. The tank is aerated because oxygen is essential to sustain the process. NOTE: the aeration pipe doesn’t go in at the very bottom of the tank; if it did, the air wouldn’t be able to circulate as efficiently.

The bathtub under the corrugated iron is the small worm farm that serves this 30-hectare farm.

Vermicast in the worm farm.

This is an old batch of fish hydrolysis.

FOLIAR SPRAYS

JAFF shares that trials were done and an article published by SAAGA saying that foliar feeds don’t work. But, JAFF says, Graeme Sait (one of his podcast providers) pointed out that there was a fundamental error in the trial relating to this in that a ‘sticker’ wasn’t used or, if it was, it was obviously the wrong sticker. This resulted in the feed washing off.

Graeme insists that avos can be fed foliarly but, because their leaves are so waxy you need to get a leaf flush and use a sticker to ensure maximum penetration. That being said, JAFF only applies a foliar feed during flowering to supply boron, at the rate required post leaf sampling. Generally, if the leaf sample shows there’s less than 30ppm he’ll do 3 sprays. Anything over 45ppm does not require supplementation. The first spray is at cauliflower stage, the second during full bloom (JAFF includes zinc and calcium – below 1% – in this application). And the last spray, when the fruit has set, is just zinc and calcium.

John Kempf has taught JAFF that, once the ‘flower’ is fertilised there’s a 14-day window during which the tree determines how many cells will make up that fruit. It makes this decision based on calcium and boron levels. Too much potassium at this stage is bad.

TESTING

JAFF’s preference is for the Albrecht method of soil sampling.

This is a soil management program wherein the soil analysis measures the nutrients available to the plant from the soil by performing specific nutrient tests in the same way every time. Such measurements, related back to the soil chemistry, effectively reflect the soil’s ability to provide the elements (in the form the plant requires) for both top production and top quality. The test results in most instances will show a correlation between yield and the balance between soil nutrient levels.

KEEPING pH IN FOCUS

“pH is key in the availability of nutrients,” says JAFF, “You lime to help your pH which affects the base saturations of the various elements.” He recommends a book called ‘Hands On Agronomy’ by Neal Kinsey. This book explains how the soil is more than just a substrate that anchors crops in place. It’s an ecologically balanced system that is essential for maintaining healthy crops. It unpacks the “whats and whys” of micronutrients, earthworms, soil drainage, tilth, soil structure and organic matter in detail.

Long internodes are signs of a happy healthy tree that will be able to carry a good crop in the following season. Big leaves are also indicators of high potential going into the season.

These holes are signs of a slight boron deficiency.

Another sign of boron deficiency is when the small avos grow off at an angle like this.

PATIENCE AND TIME

JAFF explains that patience is required … “If you have a zinc deficiency, you’ll supplement the soil but you have to wait for roots to take it up, then it is stored in the trunk for a while – only in the next flush might it come through to the leaves.” He goes on to say that nothing works quickly except maybe a nitrogen spray – everything else requires patience.

JAFF applies boron through the leaves and the soil. “If you are late with soil application, you can’t miss the foliar one but, if you’re on time you may not need the foliar one,” says JAFF.

He adds that spraying boron is not expensive because of the low volume – 150g/100l – which works out to less than 1kg per hectare.

JAFF says he can see the ‘fruits’ of his focus on soil health in this orchard. Previously, a heavy yield one year would mean not a single avo the following year but, even after 35 t/ha last season, there is still a bit of a crop this year (zoom in). All the little green sticks have baby avos on the end.

PESTS

FRUIT FLIES

“For now, that’s the only thing we struggle with,” says JAFF, “there are 3 different species; Natal, Marula & Cape Fruit Flies.

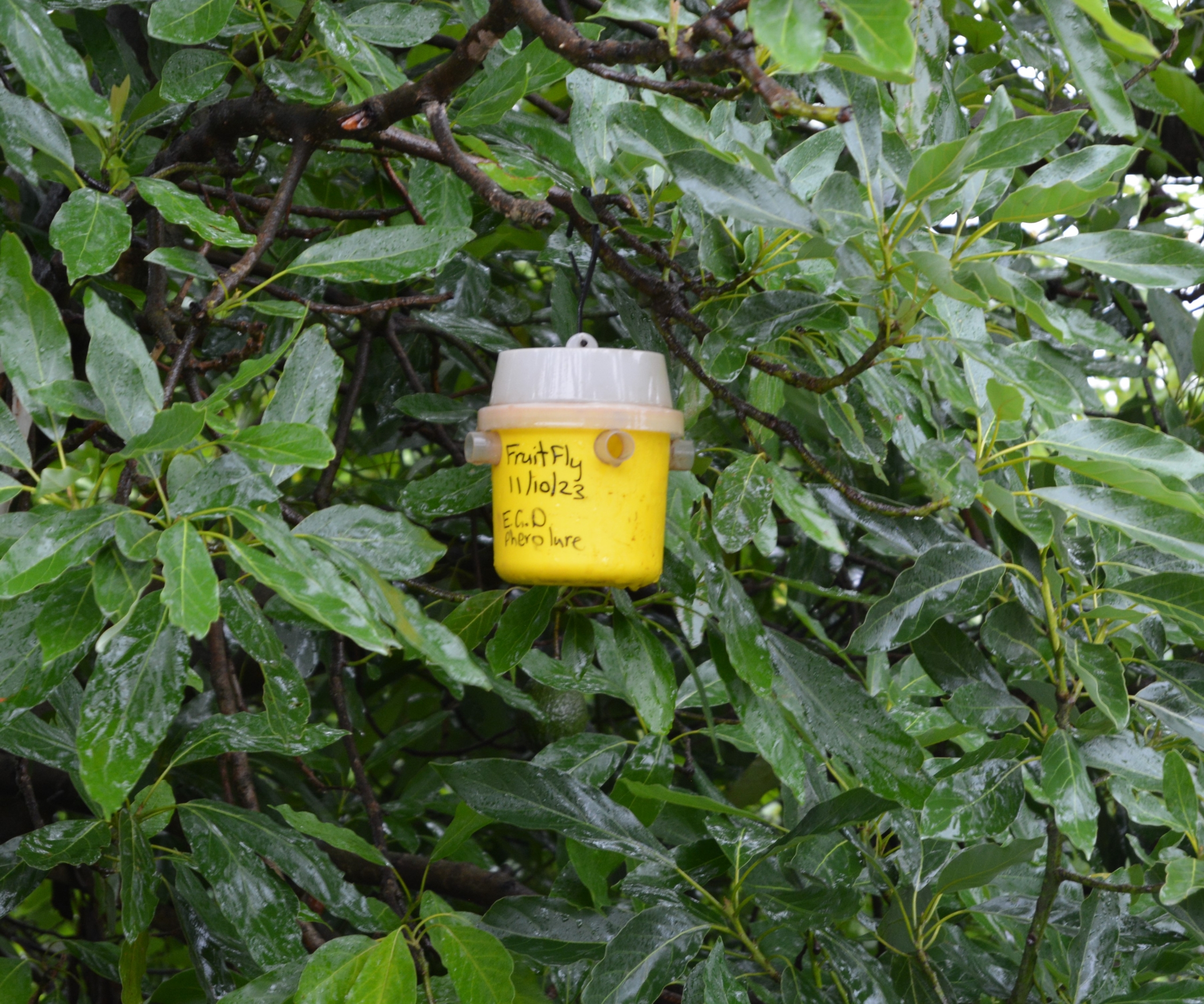

They monitor census traps which are placed one in 5 hectares. JAFF reports that once the counts were sky-high and yet there is only minimal damage to some Rinton orchards, nothing anywhere else. He wonders whether this has anything to do with the health of the trees. A stung fruit will have a little white exudate round the sting.

Census Fruit Fly traps

When counts start to climb; the threshold is 7 to 10 flies per week per trap, they prime the poison traps. JAFF has found this to be an effective, affordable and efficient way of dealing with the flies. They mix a pheromone and poison together and dip sponges into it. These sponges are protected by a little ‘lid’ and hung in the trees. 400 are used per hectare. This eliminates the need to spray which not only saves money but also the environment and means there’s no withholding period.

Simple, affordable, effective fly traps

A small sponge, soaked in pheromone and poison is protected by an upside-down plant pot base that JAFF has custom-made in yellow.

AVO BUG

JAFF reports that they had a bit of avo bug, on the Fuerte only. As they don’t export Fuerte, they decided not to spray as the chemicals indicated for this insect is deadly across everything and he valued the orchard life over the damage the avo bugs were inflicting. “For every farmer, it should be a well-considered decision,” JAFF says, “rather than a knee-jerk reaction.” Sometimes you do more harm than good when you look at things with a short-term financial reference only.

JAFF says they’ve been very lucky to never have had to spray any pesticides on this farm, except for the cabbage patch.

SNAILS

Snails seem to be an issue on the small Hass trees where they devour the leaves. A few of the podcasts JAFF has listened to say that insects won’t eat healthy trees. It has to do with the sugar levels. So JAFF put this theory to the test and checked the brix levels in trees that were and weren’t being attacked by the snails. “It’s true!” he shares, “all the trees that had snails had a brix below 9. The ones above 9 (around 14) were undamaged.” Upon further investigation JAFF learnt that insects’ stomachs aren’t intolerant of high sugar levels. This is Nature’s way of making sure unhealthy plants are eaten. As we know, the prime purpose of insects on Earth is to clean up; it’s this crew who eats all the dead and dying, recycling the weak and making way for new and healthy.

*Although a snail isn’t an insect (it’s a mollusc) it’s still part of Earth’s clean-up crew.

So, JAFF knew that he had to improve the health of these trees before the snails caught a whiff. This is not an easy task when the trees are under the stress of bags, relocation and planting so he had to investigate more …

In doing so, he learnt that, as well as calling in the clean up crew, that plants can also repel them – in a very complicated process, Rho proteins of plants (ROPs) regulate a multitude of cellular mechanisms which include cytoskeleton organisation leading to cell size and shape development, plant hormone signalling and responses to pathogens which plays out in a plant’s immunity to, or susceptibility to, disease and insects. JAFF also discovered that you can spray an elixir to help the trees produce the ROPS required to heal.

As expected, this is not as simple as it sounds and he’s still testing, researching and investigating. He has learnt that Brix is not a completely reliable measurement and, in order to read anything from the results, you need to measure at exactly the same time every day. You also need to take the environment (temp and wind leading up to the measurement and what foliar sprays you’ve done in the 5 days leading up to testing) into account.

So, while he learns, he also employs a few other strategies against the snails;

- Geese: JAFF has/had a small army of feathered knights patrolling the orchards but they are pretty hard to keep alive themselves JAFF shares, “We started with 80 geese and are now down to 25. Between the caracal, genets, hawks, eagles and whatever else eats the eggs, it’s not easy to grow the flock.”

- Spot sprays of Snail-Off: As a last resort, JAFF sprays individual trees that are swamped.

- Foliar sprays: Eco-friendly sprays (seaweed, brix and other feeds). JAFF has noticed that, 5 days after these sprays, the brix of the trees would drop (but not to the low levels of before the spray) so they do help.

A few of the snail exterminators enjoying the wet weather.

OTHERS

Just before they left for Europe, one False Coddling Moth was found in a trap so JAFF says he needs to investigate options in case that insect shows up more.

JAFF says we don’t have thrips in KZN, “There’s no thrips damage here at all. Scorching and wind damage is often mistaken for thrips damage.”

And what of mammalians? “As additional wind breaks, we had two rows of maize in the interrow when these orchards were young,” says JAFF, pointing across the valley, “This attracted bushpig.” They didn’t damage the trees but did upset some irrigation in their scoffeling. Monkeys are also a terror with the irrigation because they actively destroy it by biting the pipes or pulling the sprinklers off. He hasn’t noticed, or seen evidence of, them eating the avos though.

“Porcupines are a problem with the young trees,” he continues, “they nibble around the base, ringbarking the trees.” To tackle this, JAFF went to the dump and picked up all the 500ml plastic cooldrink bottles he could find. He cut the top and bottom off, a slit down the one side and wrapped them around the base of the trees.

On one farm a number of trees were lost, during winter, to what he can only assume were rats – tiny little teeth marks destroyed the base of the tree. Almost as if they were sharpening their teeth.

DISEASES

“Cercospera is a problem for which we have to spray,” frowns JAFF. The black skins require just 2 copper sprays while it takes 5 to protect the green skins. Copper, being a fungicide, is not something JAFF likes in his soil, “Earthworms are an indicator of soil life – their tolerance for copper is a count of 150. Sadly, the soils here have a count of over 500 because of historical overuse of this metal.” In an earthworm count they conducted last year they couldn’t find any under the trees, only in the interrow. JAFF was quite disheartened that they would rather deal with the weight of a tractor than his soft, organic-rich ridges.

Here they spray copper oxychloride rather than copper hydroxide. The key difference between the two is that copper hydroxide is an inorganic compound, while copper oxychloride is an organic compound.

JAFF has sap analysis tests done and sprays according to these results. We go back to the discussion on a tree’s ability to repel attack if it’s in perfect condition, “The theory is that the tree’s natural immunity should be enough to resist fungal damage but I’m not convinced that even a primly healthy tree resist cercospera.”

And what of phytophthora? “Yes, we do have some but only in fields where there are very poor soils,” says JAFF. These were not ridged and the plan is to retro-ridge (after the fact ridging) at some stage. The phytophthora-affected trees are injected with the standard phosphorous medication.

This tree is struggling with Phytophthora. The field is predominantly shale. Note the lavender in the foreground – intentionally planted all over the farm to diversify the foraging smorgasbord for insects.

HARVESTING

JAFF says he’s seen a positive result when he puts the harvesters in the ‘big picture’ … “I explain that the fruit they pick today is only going to get to the final customer in a minimum of 6 weeks from now and that anything they do in handling this fruit today will show up by the time it gets there and affect the results for all of us.” He then tells them, practically, how they need to take care eg: don’t leave lugs in the sun, handle fruit carefully, deflate tractor tyres for a gentler ride when transporting fruit etc. “Six weeks from now, every mishandling will show up so I encourage them to be honest and put an avo one side if they dropped or scraped it. Honesty and care are fundamental in the harvest,” says JAFF.

One area JAFF admits he needs to work on is productivity; the harvesters work on a scoff system (quota) where they’re paid per lug. They start at 6am, sometimes 5am, if it’s light, and, by 10am, some of the quickest are done. Despite his efforts (and incentives) he can’t get them to carry on. The only way to get them to pick more is to increase the scoff but he can’t keep doing that because some can’t keep up.

Once clipped off the tree, the cut point of each avo is dipped in kronos which is held in a sponge in the harvester’s hand. They then carefully place the avo in a bag and, once full transfer their load to a lug box.

GREEN HOUSE GAS EMISSIONS

This operation is Global Gap and CESA Social accredited and they have a 100% carbon neutral rating which is more than what’s required. JAFF has even included the pack house fruit (from other farms) into the equation and all the deductions involved in transporting that to the final destination and he’s still above where he needs to be. He puts this down to the increasing carbon in the soil and how this is increasing year on year. It’s also why he’s cautious about adding biochar to the soil and possibly skewing the results inauthentically.

JAFF was astounded by how carbon-focussed Europe is, “You hear about it everywhere so it is definitely a focus if we want to supply Europe. Portugal, as a country, is completely carbon neutral. There’s no coal-power at all; it’s all hyro, solar or wind powered. They plan to grow this further by putting more wind turbines out at sea. They’re also putting solar panels on the surface of their hydro-power generating dams. This helps cut down on evaporation as well.” JAFF convinced me that GHG (Green House Gas) emissions was worth a little research, especially for farmers who plan to stay relevant in an evermore environmentally focussed European market; the good news is that orchard farming is a good place to start. Here are some of the factors that reduce GHG emissions and improve farm performance:

- Cover crops: Non-commodity crops planted in between rows of commodity crops or during fallow periods.

- Conservation tillage: A range of cultivation techniques (including minimum till, strip till, no-till) designed to minimize soil disturbance for seed placement, by allowing crop residue to remain on soil after planting.

- Rotational or mob livestock grazing on pasture: Grazing practices that maximize plant health and diversity, while increasing the animal carrying capacity of the land.

- Anaerobic digester: Enclosed system in which organic material such as manure is broken down by microorganisms under anaerobic conditions.

- Windbreaks Plantations: usually made up of one or more rows of trees or shrubs.

And here’s a couple things that add to GHG emissions and therefore decrease a farm’s score:

- Purchased electricity

- Mobile machinery (tilling, harvesting, transport etc)

- Stationary machinery (milling, irrigation pumps etc)

- Refrigeration and air-conditioning

- Drainage and tillage of soils

- Synthetic fertilisers inc adding urea and lime

- Burning of open savannahs or crop residues

For more info, have a look at this: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/GHG%20Protocol%20Agricultural%20Guidance%20%28April%2026%29_0.pdf

Took me a while to see what JAFF was referring to when he said this colouring makes him happy – he explained that, when the fruit is small, the stalks have a particular colour that changes the overall hue of the tree (light green). Only when you zoom in do you see how heavily laden this tree is with small avos.

This tree is literally dripping in avos.

PACKHOUSE

While JAFF and his wife are a true team across the entire operation, the pack house is where she invests more of herself. She has a BCom as well as a degree in Dietetics and is proving to be a resounding success in the industry.

On their recent trip to Europe, they visited Halls International and a Kiwi operation (their packhouse also caters for this fruit). One of the greatest gifts on this trip was an appreciation for the scale of the world markets; they visited Rungis – the world’s largest fresh produce market. It’s not open to the public. The complex covers 232 hectares which is slightly larger than the Principality of Monaco (and many farms!!). 13,000 people work there every day and 1,698,000 tonnes of products are brought in annually. Almost as exciting was seeing their own packhouse boxes in Europe, “The fruit was gone but the boxes were there,” laughed JAFF.

The JAFFs’ packhouse capacity is 40 tonnes per day (July to Dec) or 2500 tonnes per season. (450 of these come from their own farm.) The expansion project currently underway will ramp this capacity up to 4500 tonnes avos and 3000 tonnes kiwis.

JAFF says one of the toughest aspects about running a packhouse is the farmers’ view that a packhouse is a hospital and that, somehow, their poor-quality fruit will improve once delivered here. “Last year we received 150 tonnes into the packhouse of which only 6 tonnes was exportable.” The leading issues were hail damage (at 6%) and wind damage followed closely by lenticel.

JAFF knows that the pack outs up north are far better; around 80%, whereas the reality in KZN is closer to 25 to 30%.

Please forgive the poor quality of this video but I really wanted to share the impressive contraption JAFF built to empty the crates. The extremely rounded reed cultivar (a customer’s crop – not JAFF’s) were rolling too swiftly so JAFF was making in the moment adjustments while I was videoing.

After the avos have been sprayed, they’re dried.

Then sorted.

And then there’s a traffic jam caused by the high-speed reeds.

After that, the avos are sized.

And then packed. JAFF has developed these packing cases that allow for better airflow, are water resistant and reusable.

Finally, the avos are stored in refrigeration units. JAFF has modified these to improve airflow and temperature control.

And, just like the avos in the cold room, it was time for me to leave. It had been a privilege and honour to spend the day with this remarkable farmer who is as open to learning as he is to teaching. Without incredible people like this, TropicalBytes wouldn’t be able to share the invaluable insights like those detailed in this story. From the depths of my happy heart, I thank you JAFF, on behalf of all those farmers who have read and learnt from your experience and expertise.

Thanks is also due to Derek, from SAAGA, who inspired JAFF to share his knowledge with TropicalBytes. I also wanted to kudos SAAGA on helping to secure the industry’s future through it’s work in world markets. When JAFF was travelling in Europe he was speaking to some Italians who said they didn’t know how to eat an avo. They’d bought them and eaten them hard and/or rotten; obviously they decided that they didn’t like them and wouldn’t buy them again. An important role of SAAGA is to educate new markets. This happened in England, and per capita consumption went from 0,3kg to 1kg annually. This market development was the fuel behind the spike in the avo industry (when supply couldn’t meet demand and prices went up). Vital work! Much appreciated.

Okay – I said I was going … I’m off.

Until next time, Adios.

X