Just for a change , it was a cold, wet and rainy day in KZN when I visited JAFF 35 out near Greytown. His name had come up during a number of searches for top farmers and I was surprised when a relatively young man met me as I slipped and slid around my car to greet him. For the amount of accolade he received, I assumed he’d have needed time to amass that, and therefore be older. In fact, JAFF hasn’t even grown up in farming; he started out as a Game Ranger, making his achievements in Agriculture are even more impressive.

I had contacted Subtrop for their suggestions as to who they considered a Top farmer or would make an interesting read; Derek shared the opportunity with JAFF and, as he has chosen a regenerative route, he thought he’d have something interesting to share with the readers – thank you to both Derek and JAFF for making this story possible.

Gosh – as I start writing this story and go through the pictures, I’m reminded what grotty weather it was that day (and, it feels like, every day since then!)

The view out my windscreen as I wait for JAFF at our prearranged meeting point.

But, we’re not soluble and a good story will not be thwarted by precipitation!

Besides, I’m really excited about this one; it’s another first! Our first avo-JAFF in KwaZulu-Natal.

Meet JAFF 35 …

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 6 December 2023 |

| Area | Between New Hanover and Greytown in KwaZulu-Natal |

| Soils | Mostly Huttons; 50% clay. |

| Rainfall | 800 – 900ml annually |

| Altitude | 1100m |

| Distance from the coast | About 120kms as the crow flies |

| Temperature range | -4°C to 40°C. Below 0°C only about 4 nights per year, usually early in the morning. |

| Varieties | Mostly Hass – 60%, 40% green skin (Ryan, Pinkerton, Rinton, Fuerte) |

| Hectares of Avos | 40ha in ground now with plenty more expansion planned.

Ceiling for JAFF would be around 50ha per full time manager. |

| Diversification | Pack house for avos and kiwis |

SOME CONTEXT ON OUR JAFF & HIS JOURNEY TO THIS POINT

This is the story of a farmer who took the scenic route to his destiny. He wasn’t born into farming but his ties to the earth and the outdoors were always strong. JAFF studied Eco tourism Management and then practiced these disciplines as a guide in the Kruger and a few neighbouring countries.

He spent time on sustainable, one-home, micro-farming projects for an NGO in St Lucia, here in KZN. It was here that his passion for agriculture grew and he soon accepted that he needed to do this for himself.

HOW’D YOU GET INTO AVOS?

Once he knew that farming was the plan, he and Mrs JAFF started looking at the options. They considered pineapples and told me a crazy story about that industry; like most produce, there’s a peak price season. For pineapples, it’s 2-weeks in December. The year JAFF was considering his options, one pineapple farmer cut everyone out of the JHB market by buying 20 000 lids with the 2 000 boxes he ordered from the leading box supplier in JHB. This effectively left no lids for the rest of the farmers and, without these, they couldn’t send their fruit out. The lids took 2 weeks to make and, by then, the window had closed. The mean farmer had the entire JHB market to himself for 2 critical weeks! JAFF was understandably concerned at this crazy event and it played a part in him searching out other options. They considered sugar, macs and avos.

They found this farm in 2014. “The only one we could afford,” he laughs, “it had avos so we became avo farmers!” JAFF always knew he’d really like to farm orchards/trees.

He’s eternally grateful for the soft loan from family that made it possible BUT, JAFF says, if you have a dream of farming and think access to the vocation is barred, don’t be discouraged. He’s learnt that there are always opportunities for passionate farmers as there are many landowners who can’t or don’t want to farm themselves and are looking for eager farmers to make good use of their land.

In 2018, JAFF added another farm to the operation, about 10km from the first one.

The original orchards covered about 27ha with some trees having been planted in 1986. They have a total of 40 hectares in the ground now with an expansion plan for an additional 5 hectares per year.

He says his ceiling would be governed by the number of suitable managers he could employ, “Avos cannot be ranched – they’re a demanding crop and, I believe, no single person can manage more than 50 hectares well, but it depends on your management style and how in depth you want to go.”

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

JAFF has wanted to diversify and has tried a few horizontal options; one being proteas. He soon discovered that they flowered right in the middle of the avo harvest which put paid to that journey. Since then they have chosen to pursue vertical integration into avo packing – more on that later.

They’ve also expanded their avo orchards by leasing other existing orchards. In 2019 a lease went out to tender for a 12ha avo farm, and JAFF put in a successful bid. It’s been a few years now and JAFF has developed a relationship with his ‘landlords’. When they decided to diversify and commit some of their local forestry lands to avos, they approached JAFF to see if he would farm their avos, on their land. The initial plan was for 20 hectares but JAFF soon convinced them to ‘Go Big or Go Home’ and the project grew to 150 hectares. All the avos will go through JAFF’s pack house.

JAFF’s operation now has 3 stable pillars; his own avos on leased and owned land, the packhouse and a management contract of avos. He’s comfortable with this and the opportunities for growth, in every aspect, are exciting.

On my way to the farm, I was convinced I’d taken a wrong turn; there was plenty of forestry but not a single avo to be seen anywhere! Eventually, shortly before I was about to shout for help, an avo farm popped out from the mist. JAFF explains that his farm was part of a much larger farm that was sold to SAPPI. The original owner kept back 30 hectares and planted avos. And that’s why they’re surrounded by a sea of timber!

JUST A COUPLE CHALLENGES

Whilst putting this story together, I realised how many challenges JAFF has faced since he got here. I think JAFF might also be surprised when he first reads it as he was incredibly positive during the interview; maybe because they have overcome almost all of these challenges.

FROST: In JAFF’s first year on the farm they were “demolished by frost”. They’d only been here for 3 months. Half the crop fell off the trees. JAFF says, “Thankfully we were ignorant and couldn’t fully appreciate exactly how much trouble we were in.”

Frost pocket where most of the trees have died from exposure.

Similarly to JAFF 28, this JAFF also sets hay bales alight if frost is expected which is usually the first night after a cold front. He explains that he is using the smoke to create a ceiling rather than using the flame to increase temperatures like I understood JAFF 28 was. They open a little hole in the bale and light that – the smoke streams out and forms a blanket under the inversion layer. A 25kg bale lasts 35 to 40 minutes.

I spent a little time investigating the theory behind this and here it is: temperature inversion is the phenomenon in play; it happens when a layer of warm air traps cooler air close to the earth’s surface. When smoke is generated under this layer, it will collect up against it and create a barrier. Cooler air moving down the hillsides, into the valleys, will displace warmer air on the surface – this would ordinarily move up but, the smoke layer traps it and the warmer air is ‘trapped’.

Bales are accumulated in May and left in the orchards. JAFF isn’t sure whether the theory plays out in reality and whether all this effort makes any difference but, “it’s better than lying in bed doing nothing,” he says.

A temperature inversion layer made visible by the smoke.

Bales in the orchard from last winter – although they were ready, there was no frost this year.

They’ve also used mist blowers to spray very sensitive orchards with water. Here, the theory is that the water on the leaf freezes and then insulates and protects the leaf itself from going below 0°C.

Frost fan.

Frost can cause such devastation that JAFF felt investment in a frost fan was warranted. It is an incredible piece of engineering that’s been hand moulded by an aeronautical specialist. It stands 14m high, in the inversion layer. Each blade needs to perfect and within half a gram of each other so that balance is perfect. This set up retails for about R800k and covers about 7 to 8 hectares. It’s built to replace the volume of air, in that area, every 30 minutes. JAFF shares that there were issues with the generator that delayed commissioning the fan. The day before it was ready to turn on they had a bad frost but they haven’t had any since then. Isn’t that Murphy’s Law.

JAFF explains that this fan can only help in the case of radiation frost (white frost) which occurs when there are no clouds and no wind. (Black frost is the real destroyer and comes with wind.) What happens with radiation frost is that all the hot air moves up, leaving only cold air which forms an inversion layer (usually between 12 and 20m). The fan is tilted at a slight angle, down onto the avos. The theory is that it takes the warm air from the inversion layer and blows it down on to the trees.

JAFF chose to position this fan to serve a hass orchard on one of the flattest areas of the farm where the cold air drainage is particularly poor.

JAFF has also learnt that different cultivars cope differently with frost; Hass is the biggest wimp and is easily annihilated whereas Ryan doesn’t flinch! JAFF says that root stocks may play a role in the canopy’s reaction but they’ve got a mixed orchard and comparisons are clear; a Ryan and a Hass standing right next to each other are completely different with the Hass being brown and burnt and the Ryan still holding its flowers! Apparently Fuerte also manage fairly well through a frost.

Of course older trees fare far better than youngsters because they have more leaves and can afford to lose some. This volume of leaves also creates a little microclimate inside the tree where JAFF has recorded temperature differences of up to 4°C compared to outside the tree canopy.

MARKETING: JAFF and his wife started off marketing the fruit themselves; they had a little Toyota Yaris that Mrs JAFF would load up and drive to Pinetown & Durban to sell whatever she could to the restaurants.

PACKING: Before they could afford equipment, the JAFFs were washing avos by hand while watching Carte Blanche on a Sunday night, ready for Monday’s delivery. As soon as funds allowed, they bought a washing machine and, with that, the packhouse was born. It grew when they added a 2nd hand single lane sizer from family friends in Tzaneen.

TRANSPORT: When JAFF started supplying JHB they used a non-refrigerated trucker. With a full load of JAFF’s avos the transporter’s truck was unable to leave Villiers because of unpaid diesel bills. It was one of the hottest days of any December, ever, and the petrol station owner was holding the truck as collateral.

Long story short; the avos eventually arrived in JHB with a core temp of 26° and, thankfully, the agent had managed to sell the whole load as ‘triggered’ fruit.

Needless to say, refrigerated trucks have been used since then AND this incident also raised the need for refrigeration in the pack house as well. They bought a second-hand cold room from a potato farmer in the Kamberg. Slowly the pack house was taking shape. When neighbouring farmers asked if they could capitalise on Mrs JAFF’s excellent marketing skills, a new business was born and the packhouse grew.

HAIL: On 1 June last year the main farm was hit by a hailstorm that wiped out almost the entire crop – they ended up exporting about 1 tonne. They’re picking there now and JAFF says, “The trees seem to be fine. The storm knocked about 20% of the fruit off the trees; everything left on the trees is damaged and can only go for guacamole or oil.”

This inspired a discussion on insurance … JAFF says they’re considering it but it’s very expensive and the insurers often impose their own criteria on what’s exportable (and therefore not part of the claim).

What else can be done to limit the impact of the ever-increasing threat of hail? JAFF says that shade netting should be a consideration … “Yes, it costs around R300k per hectare,” he says, “but a crop can yield R200k per hectare so, if you do netting and it works to prevent hail damage, then you’ve paid for it in one storm.” When my (somewhat dodgy) maths skills glitched at this point, JAFF clarified, “This is because the damage not only takes out that year’s crop but it also can affect the next 2 years depending on the severity.” Ah – okay – my maths is sound.

Hailstorms are becoming more and more common so why hasn’t everyone installed netting? Unfortunately there are many release system failures (preventing collapse) which has made investors sceptical.

JAFF raises a few other questions with regard to crop enclosures … would they improve export pack out rates (by reducing wind and sunburn)? If so, by how much? Do they affect the plant’s phenology? Early reports are that yields under the nets are dropping, possibly because the trees are in a more vegetative state in the protected environment. They feel that they are under another tree and that they need to outgrow it before they produce fruit. Could that be solved by finding a variety that likes shade? Or do we just limit avos to areas where there is no hail? And, with today’s changing climate, where is that? More questions than answers but we’ll keep you posted as we learn more.

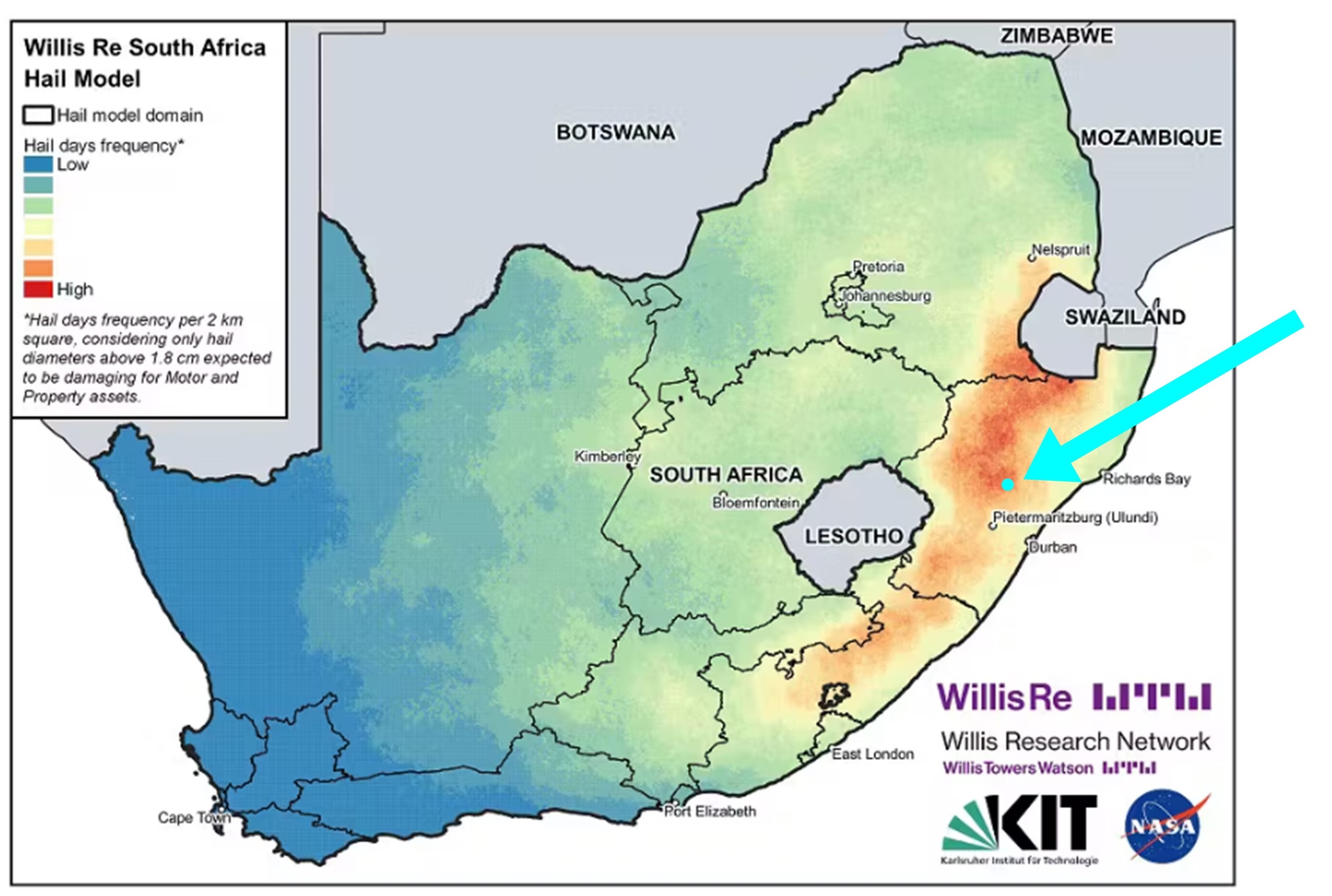

According to this map, JAFF is receiving his due amount of hail.

Hail damage. JAFF says they had hail 6 times last year although some storms were only about a minute long and may not have caused much damage.

SUNBURN: This is plagues all avos but is exacerbated when the trees are stripped by hail and frost.

Severe sunburn. JAFF says this was most likely the result of the protective canopy being destroyed by hail and then leaving this fruit exposed.

JAFF sprays the west-facing side of the trees with a protective sun screen when they’re young to protect from sun burn.

JAFF holds this poor specimen up and says there’s more than one thing going on here … a little sunburn, some wind and possibly insect and/or hail damage.

LOADSHEDDING: It’s currently costing R6 000 every second day to run the cold rooms during load shedding.

PORT ISSUES: JAFF says, “It feels like the port situation just sabotages the bottom line; we have to use the Cape Town port because Durban’s just doesn’t work. It costs R40k for a truck to Cape Town as opposed to R5k for one to Durban. That’s R35k per load that must be absorbed by the farmer. AND this money is lost to the local community.” The frustration is palpable!

WIND

One of the biggest challenges on this farm is wind and, as with frost, JAFF is doing everything he can to minimise the impact.

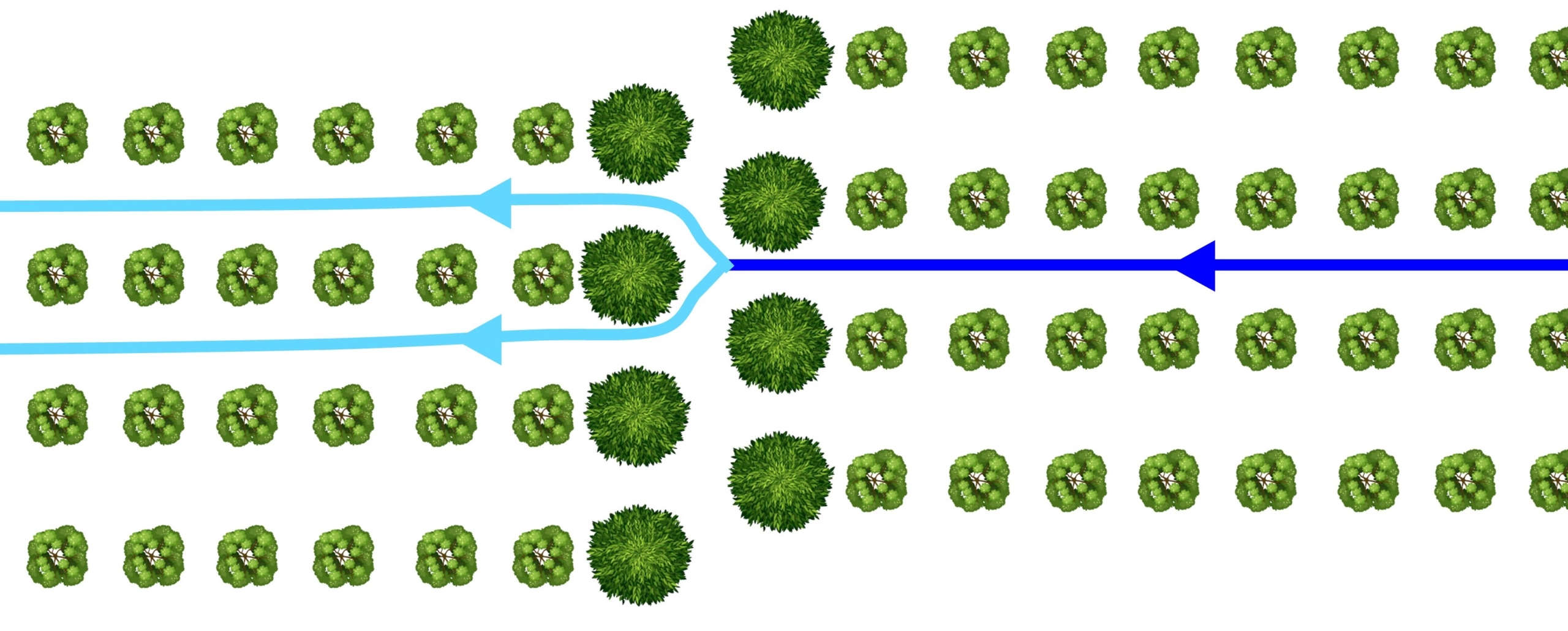

SHORTER, STAGGERED ROWS

JAFF theorises, rightly, that wind loves long passages – we only need to think back to those breezy school corridors to confirm that. So, by planting long, straight rows of trees, are we not creating a wind tunnel? JAFF has avoided this by planting shorter, staggered rows on the new plantings.

JAFF is keeping ridges to a max of 150m long and then staggering/offsetting them. Each row has a wind-break tree at the start and end. Tractors can still drive through but the ‘wind tunnel’ effect is broken.

JAFF is using Casuarinas outside the orchards and turpentines inside. He reports that turpentines have less aggressive root systems – pictured above.

When he first arrived on this farm, JAFF saw that the first 5-6 rows, next to the windbreaks, were struggling so he cut many of them down. He regrets this as he believes that the wind damage is greater than the damage caused by these trees on the adjoining avos.

This tree is under the neighbour’s pine trees. JAFF says that pine needles acidify the soil. Notice how different the general, surrounding undergrowth here looks.

Wind damage.

SCREENS

JAFF has tried to limit the impact of wind using netting. Trees that have had this protection do have bigger, darker leaves than the ones that didn’t have. As the cost of new netting is somewhat prohibitive, JAFF has been using second-hand cloth.

LIVING SCREENS

As a more affordable solution, he’s now trying napier fodder as well; every 2nd row in high wind fields and every 4th row in less windy fields. In the alternate rows they plant a cover crop – and have used maize which was a small cash income as well. “It’s not really worth the effort though,” frowns JAFF, “we’ve also tried a sunflower, sorghum and sunhemp mix before but they don’t get up to the required height in time for the really hot berg winds that come through in Aug and Sept.” JAFF warns that napier fodder needs to be planted about 3m away from the trees as it encroaches and is a fire hazard. This planting distance can be a challenge if you’re in a high-density orchard.

THANKFUL FOR THE WINS

Okay – after going through all those challenges, we need to balance the scales! JAFF says that they are incredibly lucky to have grown their business successfully on the wave of avos. The price was so healthy (for sellers) during one December that they were getting R600 for a an 18kg bag of rejects! It even spiked up to R700 at one point. And, after hearing about all the hazards of avo farming, we can hardly begrudge farmers a good price every now ‘n again. JAFF goes on to say, “The local market is now very different although there was a good run late in 2022. There are currently a lot of people planting avos so the local market will be affected by this growth in supply.”

JAFF explains that a shift in markets (from a flooded local market to opportunities abroad) changes the whole dynamic of your farm because now, you need to gear up for export and cater for the timing demands of that market. As this farm is generally cooler, compared to most avo-producing regions, it has traditionally filled the local late season gap and that meant that fruit was hung late, often at the same time as the next crop is setting. The strain on the trees plays out in an alternate bearing pattern. This is something JAFF has been concentrating on and is starting to make headway (more under nutrition) but what he says about a shift in markets affecting farm dynamics is incredibly interesting and an important element to factor into yield forecasts and expectations.

CAUTIOUS ABOUT ADVICE

Whilst the whole purpose of TropicalBytes is to learn from successful farmers and share that wisdom with those eager to improve, JAFF throws a huge caution in here that I feel is important, especially with this crop; he says “Avos are very farm specific. That makes it hard to know what will and won’t work for others. In fact, I often find myself farming each tree as an individual! Despite all the research and guidelines, there don’t seem to be definitive norms so my advice is to test, watch and follow your farming gut – only you will know when you’ve found your sweet spot.”

JAFF is a self-directed researcher. He endeavours to validate everything he’s told rather than believing it off-hand and he cautions that there’s a lot of opinion and misinformation out there. In researching he has also learnt so much more and ascertained who the reliable resources are.

Although JAFF has never farmed macs, he believes they’re easier than avos. By way of comparison, he says “In macs you can be concerned if you have a 1% mortality rate. In avos, if you have 5% mortality rate, you’re doing well.” He does concede that this stat is area-dependant and might be different per region but here, where it is very wet and cold, avos die for almost no reason at all.

FARM ETHOS

MAINTAINING INSECT-FRIENDLY ENVIRONMENTS

And so, with all these factors acknowledged, JAFF came to a simple conclusion; the only way he was going to get this right was with a regenerative approach. Which, with his background in conservation, was a natural solution.

He laughs as he shares that it wasn’t as comfortable for his neighbours – most of the community here are German and we all know that, as a generalisation, Germans are more at ease with neat and tidy than they are with the “wild ways” of regenerative farming.

Whilst it may look neglected, it’s anything but! The life in these orchards is complex. Although most of it was hiding from the rain during my visit.

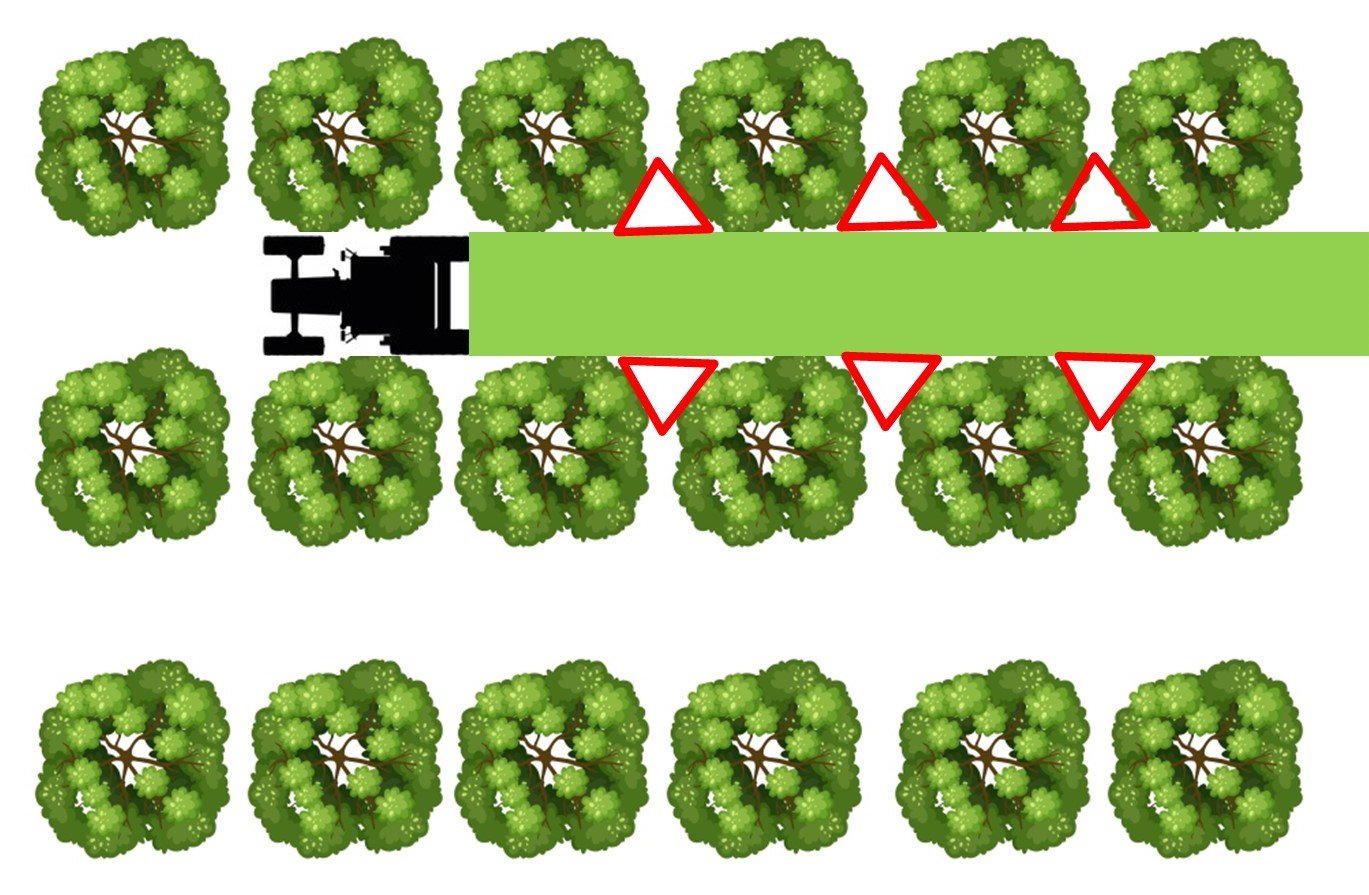

JAFF slashes every second row on a rotation basis. This allows for a balance between accessibility, order and diverse insect habitats.

After the row has been slashed, the disc mower comes through and cuts down the growth on one side of the ridge. One month later, the other side is maintained. All organic matter is left in the orchards. It makes sense that, by slashing everything, insect habitats would be removed and they’d either leave (we need diversity) or move into the trees which would result in pest damage issues.

ABSOLUTELY NO HERBICIDES NEAR THE TREES

JAFF doesn’t use any herbicide in the orchards, not even around the sprinklers which are under the trees. Instead, they control growth mechanically. “Yes, cut pipes are a headache and we have to move the sprinklers but I can’t see the logic in using poison,” says JAFF, “That poison will impact the soil life and therefore the trees. There are better ways to farm.” The turning point to stop spraying herbicides came when they were planting cover crops. They planted in the triangle between trees (in herbicide zone) and in a new field that hadn’t been herbicided. The ones in the orchard struggled whilst the ones in the new field grew taller than his bakkie. JAFF realised that he couldn’t expect higher order tree roots to grow where annuals couldn’t and, since witnessing the comparison, he’s stopped herbiciding in any orchards. They do control bramble (‘jikijola’), bonga bonga, and fence lines with herbicide but no herbicide is ever used in the avo orchards.

This is what we mean by the ‘triangular herbicide zones’.

He uses Kukuyu grass to help control the weeds under the trees. He explains that they didn’t specifically plant this Kukuyu; it grew back after they established the orchard in what had previously been a Kukuyu field before.

Stinging nettle – JAFF hopes that the orchard will ‘smother’ this plant as it hurts the harvesters. Some plants are short-lived, pioneer-type plants and he hopes this is one of them.

JAFF got a big lesson by observing what grew in the zones where herbicides were used. In that small ‘triangle’ between trees, herbicides were used to control growth missed by the mowers. JAFF tried to plant cover crops in these barren areas and they struggled (small deformed sunflower heads etc.) As the avo tree roots obviously extend into these zones, how deprived were they in this toxic environment? Since the herbiciding has stopped, this soil has regenerated and is now able to support some substantial organic growth, as seen above.

Although insects were conspicuously absent on the wet and rainy day I was there, there was no shortage of evidence that they thrived there and that the ‘wild growth’ was working … this plant had been eaten and pooped on by something that may otherwise have taken his appetite out on a juicy avo leaf.

Whilst out in the orchards JAFF picked up an earlier conversation, “As humans we’ve identified things as weeds but WHAT IS A WEED?” he challenges, “Everything has a role. I don’t believe plants ‘steal’ from any other plants. Yes, they must consume nutrition from the soil that is therefore unavailable to another plant but, if a blackjack can survive in the middle of a concrete driveway, how much is it actually taking?”

He goes on the share what he’s learnt from Dr Elaine Ingram, famous for the light she’s brought to the Soil Food Web; and why he’s so pro soil biology – “you have to support and supplement life in the soil.”

As many educated humans do, JAFF brings another perspective into the discussion; “John Kempf (one of the podcasters) disagrees with Dr Ingram; he says that healthy trees bring life to the soil through their root exudates.” JAFF believes both are right and that it’s a cycle in which both the healthy tree and healthy soil are integral.

JAFF says that, when he first came to the area, his messy, ‘wild ways’ were frowned upon but, he thinks they are now understanding the reasoning and he even sees a few of the avo farms in the area following suit.

STAFF

Another aspect I found interesting about this farm is that they ran with a fairly high staff compliment per hectare; 13 full timers. But it made sense once JAFF explained, “We keep a lot of functions in-house eg: beekeeping, bailing, making up insect traps etc.” This forms a part of the farm ethos in maintaining high standards through personal investment.

HOW IS FARMING AVOS IN KZN DIFFERENT TO ‘UP NORTH’?

As this was our first KZN avo farmer, I was keen to uncover the differences between the two regions. JAFF explains:

- Timing: It’s all about getting timing right in the international calendar. June-July-Aug is when the Peruvian tidal wave hits (Peru avos land on the international market) and prices crash down to as low as 3 euros per carton. At this price farmers will be invoiced for farming and sending their fruit to Europe. This ‘bloodbath’ is avoided by KZN farmers who only start packing in July so the fruit arrives, in Europe, in August. JAFF says that avo farmers in the north of SA (a far warmer climate) cannot hang their fruit for too long and end up competing in this Peruvian market. Having other countries open up to SA imports is a solution but JAFF says not all nations are avo-eaters … this makes marketing, education and promoting of avos vital.

- Growth regulators: A growth regulator is used successfully by many farmers ‘up north’. It is sprayed on to leaves smaller than 4cm for the purpose of slowing vegetative growth. The energy is, instead, diverted into fruit development which improves set and size. JAFF says this is not in KZN’s toolbox because of the 85-day withholding period – there’s still fruit on the trees when they want to spray. Up north, they’ve already harvested their fruit, during winter, by the time they need to spray, in spring.

- Spacing: Growth regulation means spacing can be denser. JAFF explains that, here in KZN, the norm is 8m x 4 or 5m whereas it can go as close as 6m x 3m when the growth regulator is in use.

YIELD

JAFF averages about 12 tonnes/hectare. “But,” he adds, “It’s still very alternate; last year was 35 t/ha on Pinkertons, this year it’ll be about 25 t/ha and next year, about 5 t/ha. The Hass was about 25 t/ha last season but won’t be that this year.” He’s definitely seeing this alternative pattern flattening out as he develops the soil life but it takes time.

JAFF is not happy with the forecasted harvest from this orchard. Planted in 2020, it is only 3,5 years old but JAFF had higher expectations.

JAFF explained how weather impacts yield in a way I hadn’t thought about before; high rainfall in the past 2 years has resulted in much smaller fruit. This was an area-wide phenomena and therefore attributed to weather. JAFF guesses that reduced heat units are to blame.

Which brought up the discussion around whether it’s better to have more, small fruit or fewer, large fruit? (Keeping total t/ha the same). JAFF says that the price drops on either end of the scale. Count 16 always used to realise the highest prices in Europe but, lately, that peak has moved to the slightly smaller count 18s.

*Avos are sized according to how many fit into a 4kg box. So size 18 avos are smaller than size 16 avos.

The usual pack out on this farm is 30 to 50%, because of high wind damage, but there are pockets where they get 80% – this orchard is one of those.

JAFF says that Cuces do well on the JHB market if you pack them in 500g bags but he hasn’t done that recently as it’s not really worth the trouble. Cuces are small, unfertilised avos without pips (seeds) pictured on the right, above.

Zoom in and oogle at the full crop on this Fuerte.

ESTBALISHMENT

Okay – time to get into the detail of establishing an avo farm. JAFF prefers to ridge with excavators, especially on sloping land. Although it can be more expensive it does result in a better shape ridge. Bulldozers, a more affordable option, can be used on flatter fields and longer runs.

JAFF likes a tabletop shape to the ridge as it’s better for the mulch layer which can build up on top of the ridge rather than rolling off like it does on a round-shaped ridge. He makes the ridge as wide as possible with the soil available – usually about 3m, leaving only space enough for tractor access for the interrow. “When ridging, it’s important to understand WHY you are doing it; and keep that in mind when you shape and mould – are you keeping roots out of water or increasing soil depth, or both?”

Most of this farm has been planted straight in the ground; no ridging. Only the new orchards are on ridges. JAFF says that the old orchards are fine but he thinks they could be better if they were on ridges.

“The land preparation phase is your opportunity to get liming right which,” JAFF explains, “is vital if there was forestry in the soil before, like so much of the development we are currently doing.” In one field where they had pulled out gum, they’ve had to put down 30t/ha of lime! Timber is never fertilised and, to make it worse, foresters usually burn off the remaining organic matter after a harvest to minimise the fuel load and fire risk. The result is often a depleted and highly acidic soil.

He reiterates that the biggest adversary for KZN avo farmers is wind, “When planning and establishing new orchards, you HAVE to make sure wind breaks are a big part of the plan.”

In this area, sunlight maximisation is important and therefore north-south planting (“actually just North-East of North-South” JAFF corrects) should be kept in mind but, for him, cold air drainage and water drainage takes precedence over sunlight maximisation when it comes to row-direction. He says that cold air banks up against ridges and can cause undue stress on the soil and trees alike. To minimise this, they slash the interows just before winter so that the cold air can move away, down the row, unimpeded.

JAFF says that in this, his youngest orchard (and therefore highly susceptible to cold damage), the cold air banks up against the wind break at the base of the orchard and causes damage to the lower trees.

JAFF was very happy with the soil under these trees and how the roots are actively using the mulch layer on top. This particular orchard’s ridges were built using a TLB and ended up with a rounder top than he would have liked – this means that the fallen leaves tend to roll off the ridge instead of staying under the trees. A good point when you consider the width and shape of your ridges.

This is a view of the orchard we were digging in above – still can’t really see the ridges.

Another sound piece of advice from JAFF is to visit your trees before they’re delivered. “It’s much easier to be strict about what you’ll accept before they’ve travelled all the way to your farm.”

JAFF also cautioned about watching the time of year you plant, especially in a cooler area like this where the risk of frost after Feb is just too high. “Planting after Feb is risky, as the trees are too small when the frost arrives in, possibly, May.”

“But – don’t think they won’t require care in the nursery – they can’t just be left there either!” he warns.

In summary JAFF says that poor prep is just not worth any short-term savings you may have. He’s learnt this first hand in a few of the other orchards where there “wasn’t time” to burn the excavated stumps so they buried them, deep. But, in doing this, they brought a lot of subsoil and shale to the. The result; an irregular, patchy, shaley field. This has been very challenging to farm and JAFF would never repeat the exercise; he’d chose instead to delay planting by 6 months.

JAFF recommends resting the soil for 6 months after applying lime and again after building ridges IF you have the luxury of time. Another ideal is to plant a cover crop on the ridges before planting the trees. He had a nice comparison when they were able to do this in an orchard and, right across the road, they’d established another orchard and weren’t able to get the cover crop going. The difference in soil temperature was incredible, “Cover crops definitely cool the soil which, in turn, affects the life therein,” concludes JAFF.

ROOT STOCKS

Most of the older trees here are on Duke 7. Now, he prefers Bounty which, he says, is more of a dwarfing variety. “But lots of people now are also using Dusa and Velvick.” JAFF explains why he’s chosen Bounty; “We visited a farm in Kranskop where they had planted using 3m spacing; one row on Dusa roots and one row on Bounty. The intention was to see which performed better and remove the “second place”. Bounty was the clear winner. “But, it’s a personal preference and by no means applicable to every farm. I’ll use Dusa if I can’t get Bounty.”

BEARING CULTIVARS

The majority of this farm is Hass, followed by Fuerte and then Ryan. There’s some Pinkerton and then a variety I’d never met before … Rinton! JAFF says the legend goes that some South Africans in Israel tried to steal the Pinkerton variety (can’t take us anywhere!) but they stole the wrong slip (or expect too much ) – it turned out to be Rinton. In fairness, Rinton is similar to Pinkerton; it’s also a green skin only much larger. Rinton can be hung into November making it a nice late cultivar.

A beautiful Fuerte orchard.

Wind damage on Ryan cultivar. JAFF points out how Ryan hangs its fruit ‘inside’ the tree.

Another Ryan tree – JAFF explains that, when they flower, they lose all their leaves. He’s learnt that a calcium nitrate spray, at 1,5%, at night time, has helped minimise this leaf loss. It’s done at night because it is quite strong and requires the coolness of night to make sure there’s no burning.

I’ve always wondered why Maluma isn’t grown extensively in KZN and have assumed that it was a climate-based issue; Levubu having a very different climate to KZN ‘n all. But JAFF explained that it’s more a timing thing; “Maluma ripens early so, if we grew it in KZN, it would compete with the supply coming out of Nelspruit. During Jan, Feb & Mar – price of avos in Europe is high so the earlier you can pick, the better. KZN is filling the later market which is achieved with Ryan, Reed and Lamb Hass.” So, it might grow here but marketability might be an issue.

This Pinkerton orchard produced at least 35 tonnes last season. JAFF says they’re easy to prune because they don’t seem to grow too tall. Pruning really just means opening up windows. This orchard is tight with a 6m x 6m spacing so it’s important to keep it tidy.

When I heard about this performance and easy pruning I asked why Pinkerton isn’t his favourite and he said that they don’t realise great returns because they are green skins and not great for the European market.

Interestingly, Pinkertons in KZN are not as long necked as they are in the north.

CULTIVAR DISTINCTION

I’m always trying to remember the differences between cultivars and really want to be able to identify them at a glance. It’s not easy though … if anyone else is interested, JAFF shared some characteristics; “Hass is more upright growing. Fuerte smells like liquorice if you crush the leaves.” Wait – what?! Liquorice? Yes, I checked – there’s a distinct aniseed/liquorice scent coming from those leaves – crazy! Fuerte trees are also more spreading and their colour is generally darker than Hass.

Rinton leaves have wavy edges.

Rinton – wavy edged leaves. Elongated fruit shape. The trees also tend to create flat tops, like a flat crown tree. This requires specific pruning skills to manipulate.

Typical Fuerte; they love to grow along the ground.

Spreading Fuerte tree.

And that’s where we’ll leave it today. If you want to hear JAFF’s advice and views on planting, irrigation, pruning, nutrition (you’ve NEVER seen a compost tea brewing set up like THIS), how to handle fruit flies, snails and porcupines, learn about Global Gap scoring or how JAFF runs the pack house, look out for Part 2 at the end of March.

Until then, God Bless and be safe.