Part Two of JAFF 10.Avo … one of the most incredible farmers I’ve ever spent time with. Last month, in Part One of this story, we caught up on his macadamias (which was covered the last time we visited), then we dived straight into avos, JAFF’s favourites, covering orchard establishment, culitvars (this farm is where Maluma Hass avos were born), the values of benchmarking, compost making (this guy is the 3-star michelin chef of the compost world) and we stepped into orchard maintenance … today, we continue where we left off – get ready for a PROPER education about pruning avos!

PRUNING

If you thought pruning was complicated before this; hold on to your hair! The careful consideration that goes into pruning on this farm is astounding …

JAFF explains that pruning in avos is the exact opposite to macs; in macs you encourage a central leader with side branches. In avos you avoid any one branch dominating and instead encourage numerous branches from low down. Most of what JAFF implements he learnt from an experienced Peruvian farmer who spent time in SA advising on this skill. This gentleman has done years of trials on avo pruning and uses those findings to advise others.

Multiple leaders, in balance: He said avo trees need balance rather than domination. Three or four main branches are ideal and need to be kept equal and in their ‘space’.

Air flow: Air movement between and through the trees is important so keep about half a metre between the trees.

No skirting: The Peruvian expert suggested skirting as well but JAFF is hesitant there because he says that Levubu gets incredibly hot in summer – he doesn’t want the soil to get too hot; the skirts help keep it cool and that preserves the soil life. Any avos that end up lying on the floor because of the low skirts, he gives away to his employees.

Timing: Although pruning is an ongoing task, they’ll be deliberate about coming through the orchards in October to open up for copper sprays and air movement and make a few strategic cuts. Obviously this will include branches that are carrying a harvest but JAFF says that it won’t compromise the final yield.

A ‘balanced’ tree – the way JAFF likes it – 35-year-old fuertes

Crinkle cut: JAFF also explained how yield is related to surface area and that there is more surface area on individual trees with space between the branches and gaps in between them than there is in a hedge row or a ‘round’ tree. This increased surface area can only be achieved with hand-pruning.

We stopped to have a look at the neighbour’s tree so we could illustrate the crinkle-cut concept … on the left is what JAFF would call ‘smooth or round’ and on the right is one of JAFF’s trees with multiple leaders, balanced, but each in their own space with airflow and light access within the tree.

JAFF explains that this tree now has plenty of sunlight, air movement and surface area to produce a healthy crop with minimal copper sprays. These sprays will get into the tree well, when done. 35-year-old Fuertes.

Good example of a well-balanced, crinkle cut tree. “When you start pruning like this your fruit quality and quantity improves. It’s amazing how the same amount of tree, cut differently, can make such a change.” It’s all about the movement of air, the size and the balance of the tree.

Sunburn: JAFF says that the old Peruvian taught him that, if you prune correctly, you don’t need PVA. If the domination is neutralised, the branches will shade each other. JAFF doesn’t use PVA anymore and doesn’t have much burn at all. He always considers what will be exposed to the afternoon sun before he makes a cut. “If you allow any one branch to dominate; you will need PVA when you cut that back,” warns JAFF.

Gaps between trees in the rows of this 35-year-old fuerte orchard.

Compared to his bench-marking counterparts, JAFF says he spends the most on pruning although Mark’s tools have helped tremendously. JAFF is clearly passionate about pruning and how big a difference it makes to all other factors like yield, pest & disease management and general tree health.

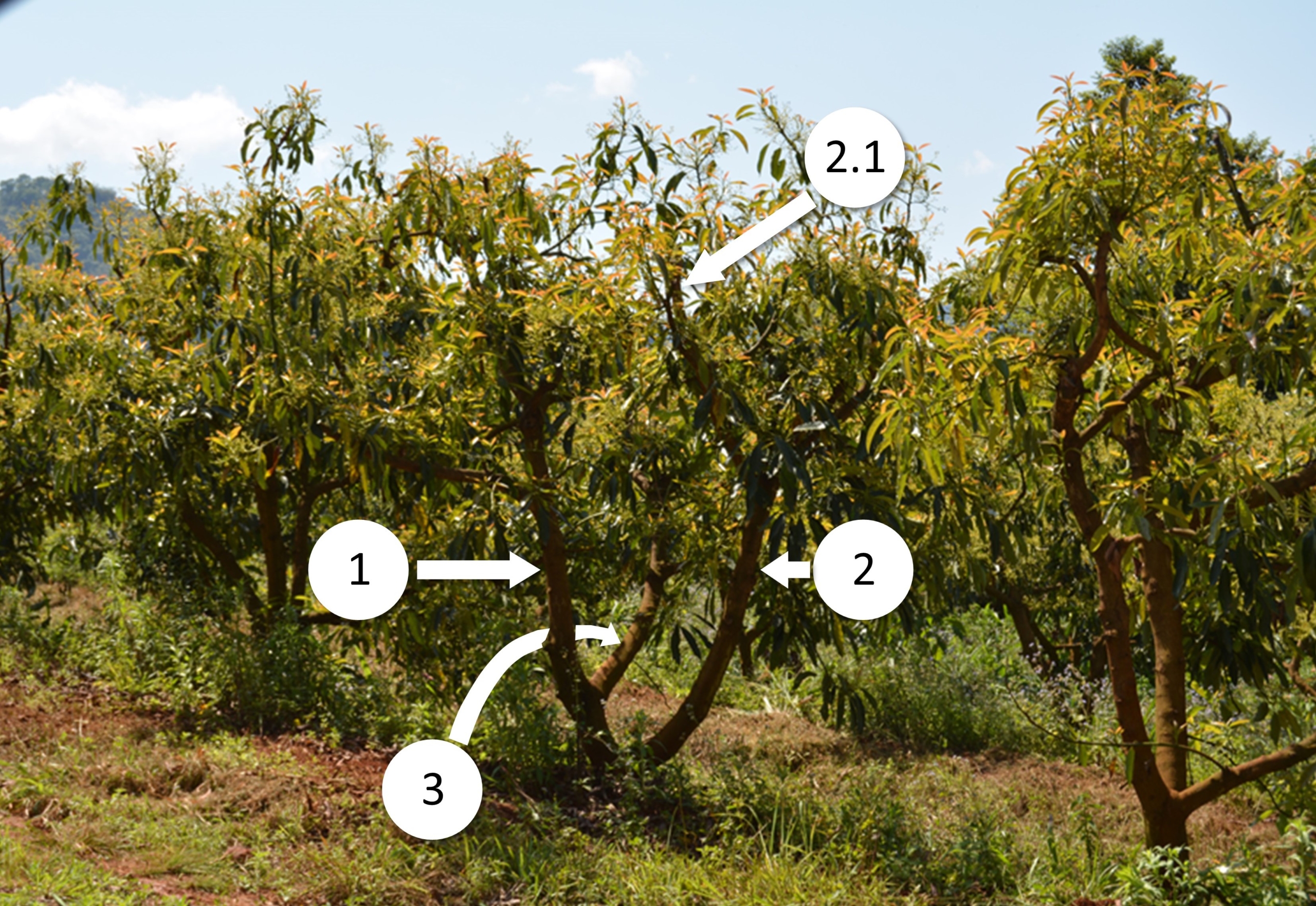

Here JAFF explains that this tree has a 3-way balance but that the top of branch 2 (at 2.1, is starting to encroach into number 1’s space and needs to be dealt with before there’s an issue.

Before on the left; After on the right. JAFF made one strategic cut that improved balance between the 3 leaders and increased the surface area, as well as increasing airflow and spray access.

Another example: JAFF took this tree from unbalanced (on the left) to balanced on the right) with one cut and, most importantly, he kept the ‘PVA’ (the inside wood is still protected from that hot, afternoon sun).

JAFF advises that you make cuts just above branches (see yellow line) so that all the energy is diverted into that branch (yellow arrow).

JAFF presents an example of what happens when you don’t cut as suggested in the previous illustration. He explains that the fruit on these branches will not be good quality and the tree has expended unnecessary energy in producing all this ‘witches broom’.

JAFF explains that pruning can be very complex, especially with some Malumas. This orchard is prone to pepper spot and so JAFF is constantly removing the downward growing branches (more under DISEASES about fungus running down on to fruit), this means that the trees end up with a lot of upright growth, as shown in the 7-year-old orchard below. So, at some stage, he has to regenerate the tree and that means allowing a young branch (like the green one shown above) to replace an older, upright branch.

7-year-old Malumas with a lot of upright growth.

JAFF uses this tree to show where the new branches will come from. If you look in the lower parts of the tree, you’ll see many new shoots; JAFF will select ones that have good joins, in the right place on the branch, and are well-placed to fill gaps – these will be groomed to take over from the old wood in years to come. With this method, he’s not only pruning, he’s also constantly renewing the wood in his trees. The short term purpose of pruning is to allow for airflow and sunlight access. Layered on top of that is the shape of the tree – balance and crinkle cut. The long-term purpose is to generate a constant supply of new, strong, productive wood.

JAFF says this shape is not ideal; the branches start off too high. He will be looking to promote some new growth lower down that can reduce the overall height and create more lateral growth.

This is what JAFF refers to as ‘chicken feet’ and he says it needs to be removed from the trees – there’s just too much going on (“like in a city like Jhb,” he says).

IRRIGATION

JAFF explains that the proof is in the pudding (not the starters ), so it’s only when the trees get older, about year 8, when they start becoming more challenging. “it’s easy to farm young avos, the troubles only start when they’re a little older.” (sounds like children!) That’s when you start paying for any short cuts or poor preparation. “Everything you’ve done up until year 8 will start showing results (good and bad) … like irrigation – you can actually irrigate yourself out of a farm, especially with avos. You need to know exactly what you’re doing when you irrigate an avo and, if you don’t, then always give less. It’s always safer than giving more.”

JAFF likes drip but has micros. He thinks both ways of irrigating are good but that drip is the future. This is based on the fact that farmers are moving towards feeding their crops this way. Drip is more expensive but micros are more labour intensive and must be checked every day. JAFF says it’s horses for courses; “You just need to know what works for you; like the trucks that get our produce to market – they’re all different but they all get to the market.”

He prefers using a small auger and checking soil moisture manually rather than expensive probes. He says he’d end up double checking the probes anyway so what’s the point?

This simple test shows JAFF that his soil is possibly a bit wet in this area.

You can judge the moisture in the soil by how much dirt it leaves on your hands when you squeeze it; lots of dirt = lots of water; minimal dirt = low water availability. Trees experience the soil the same way; if water is not freely available; the tree has to suck harder. JAFF uses a sponge as an analogy; “It shouldn’t have water pouring out of it and it shouldn’t be so dry that you can’t suck anything out of it.” Just comfortably damp.

JAFF supplies essential micro-organisms through the micro sprinklers but has to be cautious about the UV sensitivity of these microlife forms. He’ll add them in the last half hour of a long cycle so that they can move easily through the dampness to where they are comfortable living rather than waiting for rain or being washed about by too much irrigation. He generally uses a 20l drum on about 400 trees.

Small avos are irrigated once a week for one hour.

Here JAFF is showing that the roots extend in line with the leaves so the flush is almost always aligned. Makes sense that the water will drip off the leaves and onto the soil where the roots are placed.

DISEASE

JAFF says that ‘phytophthora’ and ‘avocado’ are two words that will always be in the same sentence. He’s made his peace with that. When a tree gets sick he treats it by pruning, adding extra compost and doing a phosphoric (10l/hectare) spray. He does not do phosphoric injections but does drench the soil around the tree with Grow-Agra (essential micro-organisms) at the rate of 500 litres per hectare. He repeats this in a few months.

JAFF says that, in his environment, the best thing for a sick tree is patience; it has usually taken time to get sick and will need time to get healthy. Whatever action he takes, it needs 9 months. For this reason he is constantly ‘reading’ the trees so that he can catch issues early, “the sooner you catch it, the sooner it will recover,” he believes.

It pains JAFF to spray copper for the Cycospera fungus but he has to. He knows it impacts the soil life and is always looking for ways to spray less without compromising fruit quality. Currently he sprays Fuerte 3 times a year and Hass twice but is hoping to get away with one less, on all cultivars, in the upcoming season. All the organic matter in his soil gives the microbes somewhere to hide when the copper falls.

Malumas have been challenging with pepper spot in recent years and he has changed the pruning strategy to remove older branches and increase sunlight penetration in an attempt to alleviate the pressure.

This black stuff on the branch is pepper spot. JAFF removes downward growing branches like these; he explained that the morning dew will run down the branch, taking the black spot with it, and on to the fruit where it will devalue the fruit completely.

SIGNS OF A HEALTHY/STRESS-FREE TREE

JAFF teaches us that healthy, unstressed avo trees (all cultivars) will have the vitality to push ‘umbrellas’ for their fruit. Like a mother hen protecting her chicks from the elements, a new leaf flush will grow over the flowers so that, when the fruit develops, it is shaded and ‘protected’. If your trees aren’t shooting these umbrellas, it’s a sign of stress.

That’s why balance between flowers and leaves is important. JAFF advises that, if your trees are not pushing the umbrellas, you might want to consider a flower prune but, he adds, Malumas can carry a big load successfully and their branches often grow down – this helps to shade the fruit (although that’s also what makes them get full of pepper spot).

Close up view of the developing flower umbrella.

JAFF also says that, when you’re looking at what to prune out, branches that don’t have umbrellas are good ones to remove because there’s obviously an energy issue there BUT, he cautions, when it comes to Malumas, they turn around very quickly and you’ll come back in a few days and you won’t see the flowers for all the new leaves.

PEAK

JAFF thinks an avo orchard peaks at about year 7 or 8 and will then plateau. Depends on cultivar; Fuerte a bit later than Maluma. Hass about year 5 or 6. Maluma starts bearing from year 2 but proper production is seen in year 5 or 6. JAFF once had 10,3t/ha off 3,5-year-old avo trees. The breeding of trees, roots as well as good soils built into this impressive yield.

BREAK-EVEN

JAFF needs to realise about R60k per hectare to break even, the way he farms. Depending on the price, that’s about 4t/ha (export prices). JAFF says this is where he is different; he’s happy if he can just keep farming, supporting his family and the workforce. He’s different from many farmers in that his goals don’t include extreme wealth or record yields. He just wants to enjoy the earth and all its fascinating secrets. That’s why a lot of farmers are currently getting out of farming (especially with this last season’s prices) – when it’s all about money, then that’s the logical choice. For him, it’s so much more.

HARVESTING

JAFF says this is straight forward:

1. Check for ripeness (take fruit to packhouse over 4 to 5 weeks – they’ll tell you when to pick).

2. Cut Fuertes and Maluma and dip in steriliser. Hass are snap picked (broken off at the stalk).

3. Place in a bag (no weighing – JAFF says this is unreliable and requires additional labour and is therefore unnecessary) and tip in the trailer.

4. Keep records.

He offers incentives to the permanent guys, on the tractor-trailer; they each get 3c/kg delivered to packhouse. JAFF finds this encourages them to work without watching their clocks.

The pickers get R5 per bag that they tip into the trailer – he watches the average weight of the bags within each team and has a chat if they slip below the average of 17kgs per bag. If they pick more than 40 bags they get R6 for every bag (from bag 1). Some people can do up to 100 bags per day. The harvest team is made up of 28 guys per season – all young, local, Venda men.

Harvesting costs come down when you reduce the tree size and you would think the yield would too but JAFF says it hasn’t, in his experience.

MARKETING

The Levubu window for green skins is the last week of Feb and for 2 weeks into March. In the last week of March they start with Malumas which continue until mid-May. JAFF exports whatever he can.

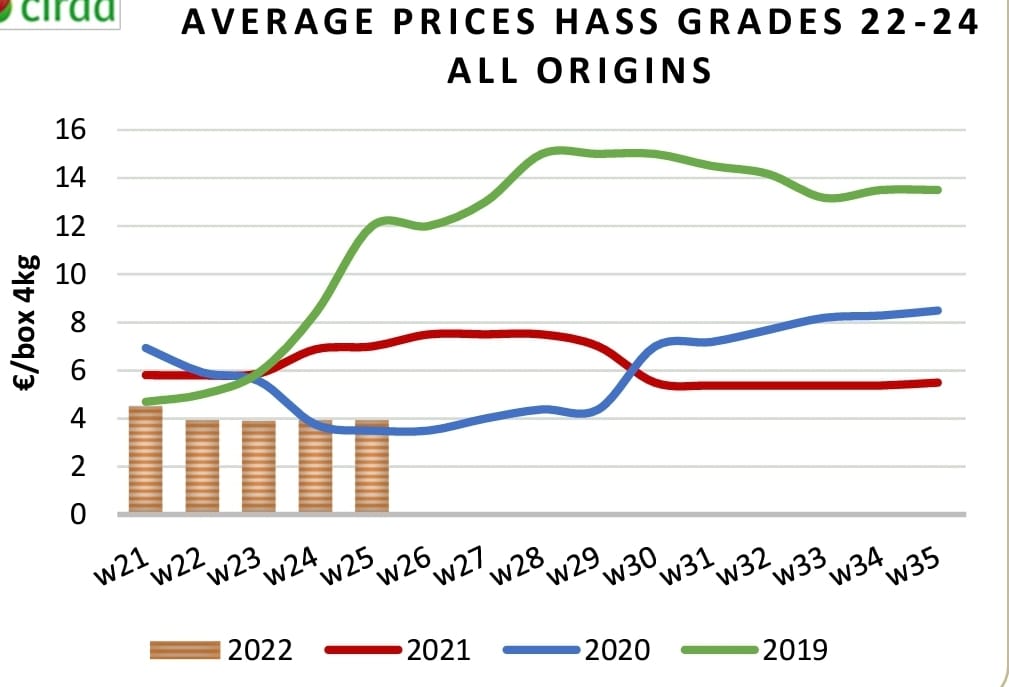

Even though the market for avos was poor this year, the farm produced well. The Russian war collapsed the green-skin price with a combination of over-supply into the European market and high diesel prices. (Europe can only handle 500-600 containers of green-skins per week. A lot of green-skins go to the Eastern Block but this was all diverted to Europe with the war.)

Historically this farm has always had fewer green skins (about 13%). JAFF’s uncle set this pattern.

This graphic shows that there’s a long way to go to get back to the bullish prices of 2019.

CROSS POLLINATION

JAFF attends study groups for both macs and avos and says that cross pollination is far more topical in macs than it is in avos. He was interested to learn more about the flower phases and how this information might be used to impact yield.

The Malumas were in female phase (on the right) while the Fuertes were in male phase (on the left) while we were in the orchards.

There are about 200 bee hives on the farm which JAFF cares for himself, with the help of his Dad. They maintain the hives and harvest the honey.

This comb breaks the seals that close off the individual compartments; then the honey can run out.

INSECTS

As no pesticides are used in the avo orchards at all, the life is prolific and very audible as you walk through the trees.

Something had made a cosy home between these two avos

Wax Scale

Pray mantis. In Afrikaans it’s a Bids-sprinkaan (direct translation; praying grass hopper)

Fresh from a pedosphere pedicure, JAFF points out heart-shaped scale that has infested a few trees. What I didn’t see at first though (and you might have to zoom in) is that many of these (like the one JAFF is pointing out) have been parasitised (eggs have been laid in it by the pray mantis). And this is what I love so much about this JAFF; that he is educated about Nature and this allows him to be confident in her work. If he sprayed, what we see above would not have happened. (Besides the expense of spraying and all the other subsequent fall-out).

The trees give off what JAFF refers to as “Honey Dough” which is ant food and, when the ants traverse the leaves after a meal, their honey dough-covered feet leave this thin black film on the leaves. It’s obviously not ideal for the trees but, to control it, the ants need to be controlled. But JAFF says this only seems to happen in ‘pockets’ – here there were 2 trees affected – so he’s not overly concerned.

We then wandered through the oldest Maluma orchard on the farm – 38 years. Some of the trees are stressed and JAFF says he will investigate the irrigation as a first call. But he was in his element as we got out the magnifying glass and got close with the “Kruger Park” in this orchard …

Sun-bathing spider.

Eye-ball to camera lens with a hungry Ladybird.

JAFF pointed out so much life on this one leaf it was mind-boggling – you really have to zoom in – especially if you want to see the cutest spider ever!

Another species/variety of pray mantis. With a photo-bombing ladybird in the background.

Another spider … and her nest?

An ant spider and what looks like its recently shedded exoskeleton.

JAFF says he shudders to think that some farmers get the pyrethroids out because they see a few thrips; imagine the balance of life he wipes out with that short-sighted move!

He also reminds me that, if I think there’s a lot of life on the leaves still on the trees, I’d be flabbergasted at what we’d find if we grubbed around in the leaves on the ground! And then there’s the soil life. The fascination with, and responsibility for, all this life suddenly hits me! And the fact that so many farmers miss it all weighs heavily.

THRIPS

JAFF says that he doesn’t mind the black thrips as these ones support pollination. It’s the lighter coloured ones he’s weary of and tries to leave a lot of growth in the orchards as an alternative food source for them.

PRICKLY PESTS

Finding porcupine quills on a stroll through the bush is always a thrill for any child (and many adults). As ‘townies’ they intrigue and fascinate us but, for many farmers, they’re nothing more than oversized, prickly rats with sharp teeth and no respect for irrigation pipes. JAFF was particularly unimpressed with these rodents when they did this to one of his trees:

Thankfully JAFF found the crime scene fairly fresh and doctored the wound with tree seal. When I was there it appeared to be healing well.

THEFT

JAFF says that theft by humans is bad but the baboons are worse because they do so much damage when they come in to eat the macs.

I’ve heard these beasts are a real challenge so what does JAFF do to minimise their impact? “Electric fences work, if you use them properly,” he says, “and guards.” But, you have to keep the fences clear and maintained and JAFF doesn’t leave them on all season … “these animals are very clever – if you leave the fences on all season, and they are hungry, they will find a way in by jumping from a nearby tree or rock, or slipping through a gate – they’re very resourceful.” So JAFF only turns the fences on when the nuts are set. This way the baboons are shocked by the fence like it’s the first time (they seem to have short memories) and they’ll be wary for a while before the resourcefulness kicks in … by then, the damage has been limited.

This camp is now surrounded by electric fence after 100 trees were stolen out the ground. The theft is sickening. And the destruction also heart breaking as the thieves damaged the remaining trees they struggled to pull up.

“Load shedding is ‘n bogger-op” AND OTHER CHALLENGES

JAFF says it like it is but he’s grateful that his soils have a lot of moisture (that insurance he mentioned) and he does what he can with what he has in terms of electricity.

On the way back from the orchards JAFF shared his concerns about the future of all farming, but specifically macs and specifically in this area (but the concerns are valid for all agriculture); he says there are 2 big things that are going to make us loose the war against pests:

1. People are too scared to trial softer options because:

a. processors award and reward farmers who have low unsound rates. They are also highly prone to framing farmers with high unsound rates as inferior; sometimes even rejecting entire deliveries when the unsound is too high. JAFF warns that farmers think carefully about whether a certificate is worth the cost of environmental damage and the consequences of that and whose goals you’re chasing.

b. The farm viability is already marginal and high unsound rates, in even one season, could be fatal.

Both these things boil down to a lack of a long-term vision, without which, things just don’t last. E.g.: with a short term view you might try a chemical to treat whatever pressure your farm is experiencing then … it works … you killed the insects, got a nice price – short term goal achieved. The next season, there’s a new ‘plague’ and you lose; you then try the next strongest chemical the next season and (if it works) you’re back on top. JAFF asks; when does this cycle stop? When will we run out of poison? He advises that farmers start considering methods that aren’t poison and, if you find something, tell the whole world – quickly! The processors won’t reward you for these trials – in fact, nobody will, except your own long-term, stable results. Every farm is different; every ecosystem is different so every intervention that humans implement will have a different outcome in every environment – this makes trialling on YOUR farm imperative.

Despite the fact that JAFF is not big on ‘interviews’, especially ones in English, he got out the bakkie at the end and said, “Jusie, now I enjoyed that!” so may this be an appeal to all the top farmers out there – share what you know; TropicalBytes is the perfect platform!

As sad as I was to leave, the time had come; the sun was setting; the kids ready for “happy hour”. But this farm will always be a firm favourite and I can’t wait to get back … maybe when we cover bananas …

Thank you JAFF for, once again, allowing me to take up your annual allocation of English and sharing all your experience and expertise with TropicalBytes readers – may you be richly rewarded!