This story captures the wisdom, advice and expertise of a highly valued consultant that I met in White River. The fact that he’s way past retirement age just makes him more prized and I am grateful to be able to share what I learnt ‘at his feet’ with you.

Roy, being a consultant, is happy that we share his identity and contact details – not that he’s looking for additional business – but he’s happy to engage with anyone looking to learn from his vast experience. He is a General Consultant, officially qualified as a ‘Professional Scientist in Agriculture’ to cover most crops, but has a particular affinity for macadamias, avocados and citrus. “But remember, I am like a GP doctor,” clarifies Roy, “when you have serious issues in a particular area, it’s best to consult a specialist.” Roy furnishes his regular clients with a monthly report that details what was observed last month, recommended actions and the results and what should be done next month – nice, simple and, clearly, it works a charm (but does mean the farmer has to play his part).

Having so much experience, and past the age of waffling, I thought that Roy would impart some strict do’s and don’ts but instead, his style is more laissez faire; he says that there are just too many unique considerations that go into every situation and this means that giving definitive advice on a general scale is simply unwise. So, instead of being prescriptive, we had a broad discussion … trust you’ll enjoy …

Roy has followed the emigration path of many others; being born in the UK and going to Zimbabwe as a youngster where he completed his schooling, varsity and early career. Career highlights were landing a job in farming sugar cane early on and then getting a bursary to study Irrigation in America. Lowlights included coming home from the study abroad to find he no longer had a job in sugar cane. He was offered a position in a citrus operation, which Roy says is the very best place to learn about pest control. But life was ‘unusual’ for the next few years while the Rhodesian Bush War played out. Roy spent a lot of time conscripted to the forces with short gaps of being home. In the stuff of novels, they found out that their neighbour was a spy (I want to say Russian spy but I might be making that up) and the citrus operation was eventually shut down for contravening sanction regulations and so he became a cotton farmer (when he wasn’t a bush fighter).

Frustrated with the ongoing war, Roy began looking across the border and managed to get a job in South Africa, on a well-established citrus farm in Hoedspruit. He and his wife were the only English-speakers in a VERY Afrikaans community but, as political aliens, they were already accustomed to seclusion. The only schools were Afrikaans. They even had to report to the police station, with their small children, once a month. Not long after that they moved to a banana farm which was closer to better schools, although still Afrikaans, but, by now, the language was no longer a barrier.

The Porritt family stayed on this farm for 12 years until it was sold. The next chapter was less than 150kms away, in Kiepersol. Here he added avocados to his repertoire but 8 months after he started here this farm was also sold! Different outcome though as these new owners were businesspeople and needed Roy’s expertise to run the agricultural side. Another 12 years were dedicated to this operation and brought Roy to his ‘retirement’ which he’d always planned to start at 60. Discovering that 60 was a little young to sit down, he started an agricultural consultancy business which, almost 20 years later, is still going strong! It was only in his early 60s that he added the “Professional Scientist” qualification to his CV as this was required in order to legally advise farmers.

Bananas, avocados and macadamias account for the largest part of his current portfolio, across about 30 farmers, but he also has extensive knowledge of various smaller plant crops.

It was in this consulting role that Roy became involved with Recruit Agri; a centre that provides practical farming experience to black university graduates. Roy delivers the lectures on the basics of farming macadamias and avos. My eagerness immediately lit up (as I smelt a shortcut to a valuable article in reproducing his course content for you all) but he quickly snuffed that idea. 🤣 This was never going to be that easy …

And so I began digging around in Roy’s avo experience to try and up earth the pearls within. Below I have strung them together, somewhat haphazardly, which is a reflection of the few hours I spent in Roy’s lounge … he and his wife were about to start a short holiday in the Kruger and I was holding up the departure 🤭.

This is what you’re in store for:

- Changes in Industry focus

- Root Stock

- Markets

- Soil quality

- The importance of Calcium

- Soil Life

- A Good Start

- Ridging

- Planting

- Farming is a business

- The biggest Pests

- Pruning

- Onion Ring

- FARMING with MATHS

Changes in Industry focus:

ROOT STOCK – the high prevalence of soil-borne diseases affecting avos has driven attention to finding more resistant root stocks. As a result, Dusa and Bounty have been developed and are proving effective – they are therefore the base of most new commercial orchards in South Africa at the moment. Consequently, yields are increasing, from 10, to as much as 30 tonnes per hectare. Roy emphasises that farmers should be investing in these improved root stocks to minimise the impact of devastating diseases.

MARKETS – In the 1990s farmers chased production volumes in order to turn a profit but, as the Rand has weakened, exporting became a very attractive alternative to maximising returns. This, in turn, forced the industry to refocus attention on different factors:

- Perishability: The limited shelf life of avos is an obvious issue here and so the focus turned to perishability. Temperature and transport are the biggest hurdles in getting product to the attractive currency holders … 36 hours from farm to port, harbour delays are standard and extensive, 2 weeks on the sea – the reality is a minimum 28-day journey from farm to fork.

- Cultivars: Foreign buyers seem to prefer dark skinned avos so, to play in this market, farmers needed to produce accordingly.

Avocados need GOOD SOILS:

In Roy’s opinion, bananas need even better soil but avos are also really demanding when it comes to subterranean quality. “As soil quality diminishes, farmers need to change crops,” says Roy, “there are other plants that will tolerate poorer quality soil.” He cites macadamias as one of those options. (although I can see many mac farmers already re-reading that statement and probably shaking their heads 🤭) Roy believes soil health is the crux of agriculture; that it needs to be tested and adjusted (fertilisers) annually.

Calcium is Key:

The uptake of this mineral is a major factor in determining whether or not avos hold their quality – and therefore essential for exporting avo farmers. It is taken up in the early stages (first 3 to 4 months) of fruit development when the cells divide and develop. Specifically, it is the cell wall structure that depends so heavily on the calcium. To meet this need, Roy suggests applications of calcium nitrate supplied as a foliar feed or soil drench.

Preserve Soil Life:

Given the rocketing cost of chemical fertilisers, and the negative impact that mono-cropping has on agricultural bottom-lines, protecting the life in soil is becoming more important than ever. Everyone has a different idea of what ‘preserving soil life’ entails but Roy explains that you can start off with simple things like using potassium sulphate instead of potassium chloride (chlorine sterilises the soil whereas sulphur supplements it).

Then, you can graduate to using mycorrhizae or other organisms to break down carbon which facilitates natural nutrition supply in the soil rather than supplement chemically all the time. “Everyone is getting into that now, especially with the price of fertiliser having tripled in the last year,” says Roy, “people are making more compost and mulches, avoiding additives that kill the soil life.” Roy adds that permanent crops, like avos and macs, lend themselves to this far more than annual crops which require soil disturbance; ploughing, digging etc. What’s also encouraging is that permanent crops are automatically enriching the soil, especially avos which drop leaves creating a natural mulch. “We expect to see earth worms and spring tails (micro-organisms) in these orchards,” smiles Roy.

Think carefully before ridging:

Roy believes these features should be considered functional rather than mandatory. Reserved for steep slopes or where there is minimal soil so the depth needs to be built up. He says ridges come with their own problems;

- erosion is far worse than on flat land.

- a ridge is like a glorified pot – it limits root growth and necessitates more frequent watering.

- there is increased water runoff from a ridge.

Planting is a critical activity:

Roy warns that planting out is a significant environmental shock for the small trees and needs to be done with care and caution. Right from removing the bag without damaging any roots, maintaining cool, moist conditions (the right amount of water together with mulch) and supplementing carefully, every step needs to be managed knowing that this tree needs to produce above average for the next 40+ years.

Farming like a businessman:

Roy highlighted the fact that farmers ARE businessmen but don’t always make the best business decisions. It’s not only about producing enough; timing also has a critical impact on the bottom line … like seasonal considerations; finding your gap where there is less competition in the market and prices are better. Consider cultivars like Carmen Hass which come in earlier in the season and therefore generally get higher prices.

Farmers can also manage the flow of product into the market to realise better prices. Avos don’t have to be picked when they are mature as they only start to ripen after being picked.

Generally farmers rely on their packers to make all these types of decisions for them but some farmers might benefit from exploring options for themselves.

The biggest pests:

My familiarity with macs is evident when I ask about pests before diseases – Roy explains that pests (insects) are most certainly a secondary concern when it comes to avos.

Nevertheless, there are a few and, in Roy’s opinion, Coconut bugs are number 1 when it comes to avos. He says there are wasps that can control these insects biologically. (supplied by Real IPM). Another biological control is Beauveria Bassiana (BB), the active ingredient in some fungal sprays, registered to control stink bug. Two challenges with this are: 1. You can’t use copper, or any other fungicide, in conjunction because that would kill the BB and 2. BB is a broad band fungus and does affect many other insects apart from the stink bugs. There is a very useful resource, published by fieldBUGS, that shows what else impacts beneficial insects and to what extent. (Fieldbugs has given permission to publish this).

I also learnt that scouting in avos is vastly different to what traditionally happens in macadamias where highly toxic knock-down spray is used to establish what’s present (by doing a body count). Export markets, “especially the Germans,” adds Roy, have stringent MRL (minimum residue level) stipulations which preclude the use of these knock-down chemicals. Because stink bugs have eyes, can see you coming, and have the wits to hide it makes scouting them rather ineffective. So, the scouting is done by looking for the damage they’ve made on the fruit. At the same time scouters check for evidence of avo bug and thrips especially early in the season. Fruit flies and moths are trapped and poisoned using a bait.

Pruning … simplicity:

I couldn’t get Roy to elaborate on pruning but, what he did say was appealing in its simplicity, “It’s all about getting light into the trees because that’s what generates flowers.” Roy says that you can’t have it both ways and there’s always a trade-off between orchard density and pruning intensity so, if you want more trees per hectare, factor in a full time, skilled pruning crew.

Onion ring answers:

Having just visited Jaff 26 https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2022-11-jaff26/ I was avidly searching for an answer to her burning question and thought this seasoned agricultural scientist would be “my man” … Jaff 26 was struggling with onion ring, especially on Beaumonts (yes, I am taking a detour back into macs but I did warn you that this was a haphazard affair and we’re learning here! Stay with me) … what did Roy think was the cause of onion ring?

Firstly, Roy educated me by clarifying that macadamias are not nuts; they’re seeds! I just had to google because I couldn’t quite believe I’d been so misled to this point 🤯 and he’s right! (not that I doubted you Roy 🤭 – okay, maybe I did) FAST FACTS: Macs are seeds because: 1. They’re dicotyledonous (two parts to the seed). True nuts are monocotyledonous. 2. The kernel is not fused to the shell, which it always is in a true nut.

Anyway, back to the onion ring … when a SEED wants to germinate, it fills with water and breaks open the shell. It then germinates (springs a shoot) and comes out. With this absorption of water, the barrier between the white seed and the brown shell (made brown by the tannin content) is broken – the tannin then stains the SEED. The closer a mac gets to germinating, the more likely it is to develop onion ring. “But why was it more prevalent in some cultivars than others, not appearing in Jaff’s A4s even after they’d been lying on the ground for weeks?” I ask Roy. “Simple genetics,” is the answer. Everything is so simple for Roy 🤔. “Some trees will just be predisposed to this condition; it may, or may not, be linked to the cultivar but is probably just a defect of that particular orchard,” elaborates Roy, which makes sense as all the trees in an orchard are usually from the same budwood. So, Jaff 26, I’m afraid that that orchard is probably just faulty 😉 …

Inside a macadamia shell … tannins are what make the brown parts dark and stain the ‘seed’ leaving an ‘onion ring’.

FARMING with MATHS:

Roy is amazed that he’s still in demand, 20 years after first starting to consult, but feels it is because of simple, common mistakes farmers make and how Roy is somehow able to see these when they can’t. As an illustration, he explained how a banana farmer was struggling with production and called Roy in for a diagnosis. What Roy found was that, over the years, the number of trees in this plantation had dwindled, to the point where there just aren’t enough trees left in the orchard to produce what the farmer needed to remain viable. Once again, I looked at Roy with one eyebrow raised … surely the farmer couldn’t have missed that simple math calculation?

But, with a couple more examples, Roy convinced me that there are indeed many farmers who are possibly ‘too close’ … I never thought I’d find myself thinking this way as I’ve always held fast to the idea that the most important thing a farmer can do is spend as much time as possible in the fields BUT the most valuable lesson I took from the time I spent with Roy is that there is, indeed, a place in farming for a desk, pen, paper and a calculator.

Roy explained that common sense is not so common after all. I was thinking that it’s easy to have ‘common sense’ when you’ve had so many years of learning … but he explained that sometimes it just takes a new perspective or some simple logic. He’s astounded at the simple errors farmers have made and the profound impact they’ve had on their results (unless he’s caught the error in time).

I’ve pondered this in the months since visiting Roy and trust that my interpretation holds value; sometimes, when we’re IN the orchard, we can’t see the wood for the trees – we need to retreat, go back into the office and make sure our basic maths is right. The more I thought about it, the more it made sense. There are many factors (ingredients) in this outcome (cake) and, if you get even just one slightly wrong (one misplaced comma is enough), the whole thing can flop.

“How much?” and “When?” are part of almost every decision on the farm – both clearly maths-based questions.

Roy says the most common ‘areas for improvement’ he encounters are around these two questions and their application in irrigation and fertilising.

Fertilising:

As a quick sidenote, Roy advises that you always consult an independent, specialist agronomist when it comes to fertiliser recommendations. A consultant’s long-term success is linked to your success whereas a supplier’s success is linked to product sales.

HOW MUCH FERTILISER:

Roy has found that either farmers are cutting back on fertiliser (for financial reasons) to the point where it really isn’t worth applying, and then they wonder why there are no results OR they do the maths wrong and wonder why the fertiliser isn’t working. So, where’s the sweet spot?

Application rates depend on how you farm:

- Per plant or per field. Are you farming each plant, like most avo farmers do, or are you farming a whole orchard or field, like many environmentalists do? However you chose to do it, make sure you follow the label or the consultants recommended rates and get your maths right.

- Application method. If you’re applying by hand, scattering granulars around the base of a tree, the rate will be different to if you are broadcasting, using a mechanical spreader. And different yet again if you are fertigating. Or are you spraying through a spray cart or micro-jet irrigation system? All methods require careful maths and even more careful calibrations of equipment; right from the size of the jam tin used in hand applications through to the drip rate on fancy fertigation systems.

- Productivity targets: What are the goals and how much do you want to invest to achieve them?

- Many other factors. There are other factors to consider here like are you exporting? (And therefore might want to apply more calcium for stronger cell walls) Or, are there specific imbalances that need to be corrected/managed?

WHEN TO FERTILISE:

Farmers also need to take a step back and carefully consider what other farm-specific factors might affect their fertiliser application;

- Soil analysis will reveal insight into soil composition and what antagonisers might be inhibiting nutrient uptake.

- Soil type and organic composition will have an impact in how well it holds nutrients which will, in turn, influence how much is applied, how often.

- Stage of development: what phase is the tree in and what does it need to support that activity? Eg: fruit set or flower initiation.

Irrigation:

If you thought fertilising could be complicated, sit down for irrigation. 😊

There is a lot of juicy information in this article https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2020-4-water/ written after I spent time with Theunis and Armand Smit – I referenced it so I could repeat the MATHS required to figure out how much to irrigate but I now remember that the Smit brothers purposely avoided that question saying that there are too many factors impacting the answer.

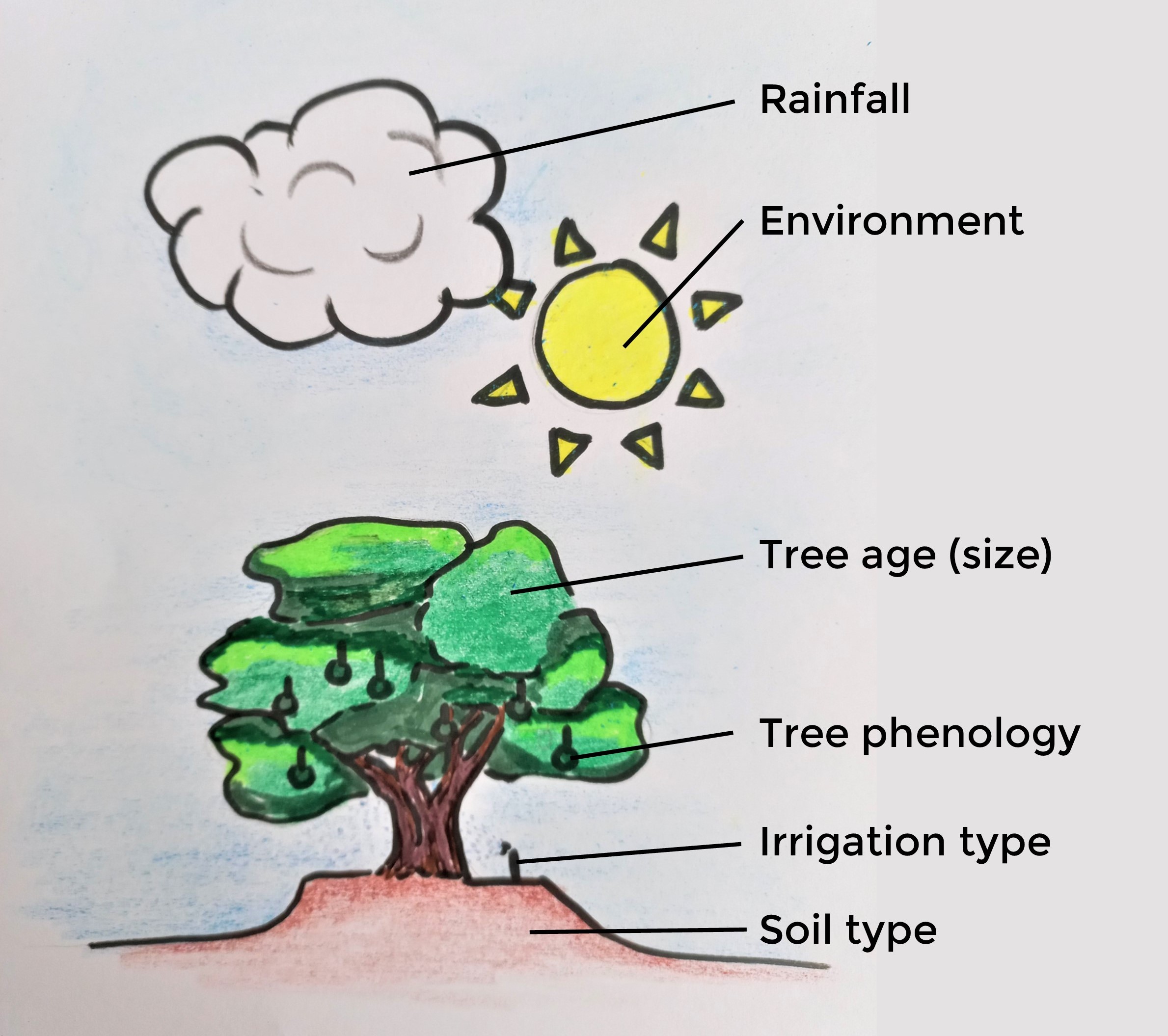

Factors to consider here are:

- Rainfall

- Type of irrigation (micros vs drip vs hand watering)

- Age of the tree

- Soil type and related water retention

- Atmospheric conditions (environment)

But, I still think it’s worth investigating the maths …

The article done on the advice given by Philip Lee https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2022-06-philip-lee-part-2/, another valuable consultant, helped me here …

A mature avo tree needs approx. 1000 to 1300mm per year but all these factors affect HOW MUCH you actually put down, and WHEN.

A mature avo tree needs approx. 1000 to 1300mm per year. Let’s use 1200mm for this example.

1200mm

You get 750mm rainfall so need to subtract that.

1200mm – 750mm = 450mm

You don’t need to irrigate the WHOLE orchard floor, just the root zone. If you’ve chosen micro-irrigation, you’re watering approx. 60% of the orchard floor. If you’ve chosen drip irrigation, you’re watering about 20% of the orchard floor.

450mm x 60% = 270mm (micros)

450mm x 20% = 90mm (drip)

Let’s continue this maths with the micro-option …

And, for micros only, you need to factor in an environmental loss factor of about 15% (evaporation on delivery)

270mm + 15% = 310.5mm

Your trees are not yet fully grown, only 80%.

310.5mm x 80% = 248.4mm

Result: YOUR ANNUAL TARGET for Irrigation IS ABOUT 250mm

What is that per hectare?

To put down 1mm on 1 hectare needs 10m3 water (10000 litres)

So, 250mm on 1 hectare = 2 500 000 litres or 2500m3 per year.

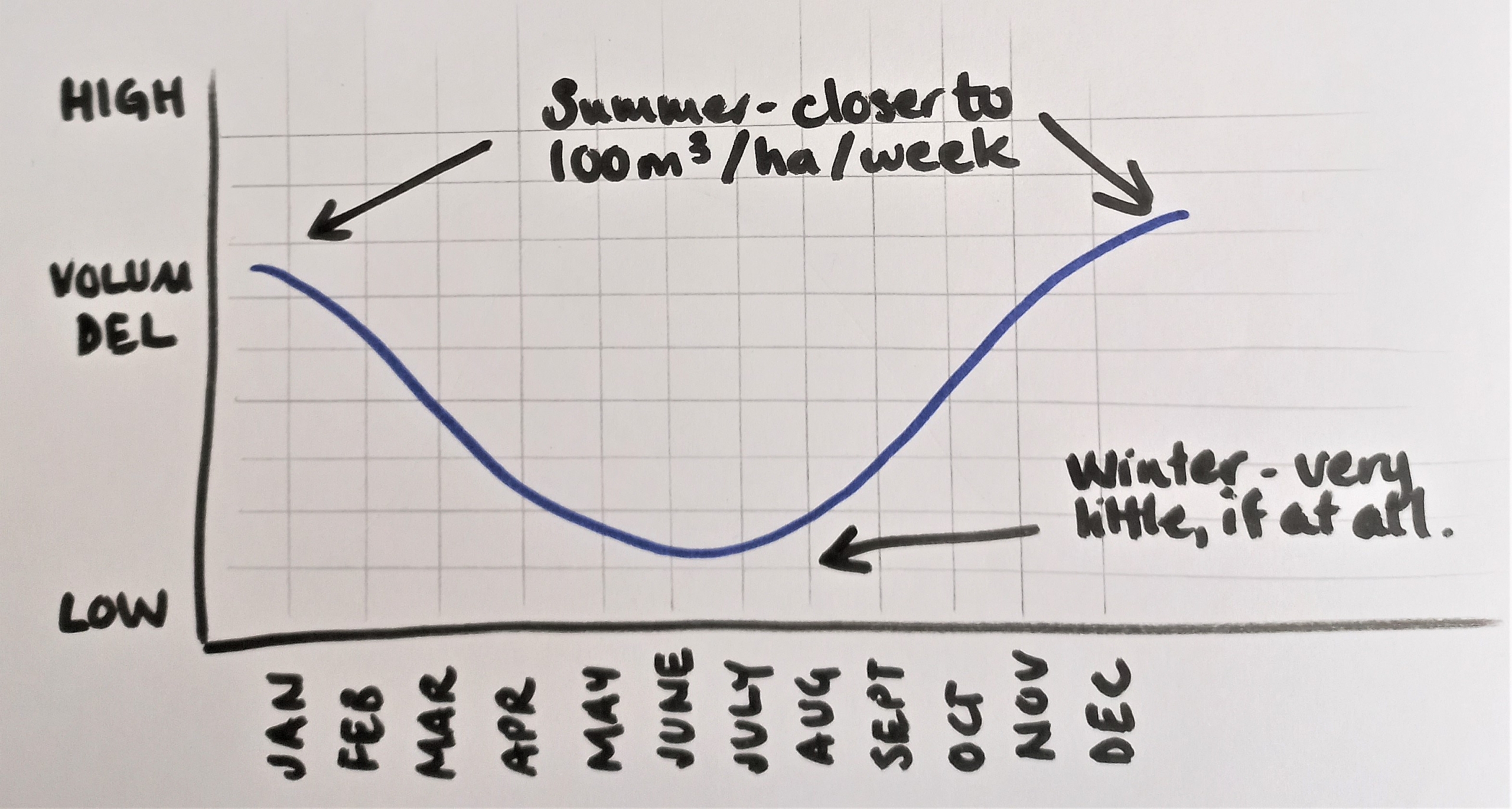

The next question is how to break that up. The success of low-flow drip irrigation has taught us that plants thrive with small, consistent doses of water rather than larger but less frequent applications. So keep that in mind.

2 500 000 / 52 weeks = 48 076 l per week or 6868 l per day per hectare.

If you’ve planted 312 trees in a hectare (standard 8m x 4m planting) and have 2 micros per tree, that’s a total of 624 micros per hectare. Each one would need to deliver 77 litres per week or 11 litres per day. If your micros are set to 30 litres per hour then you know you need to put down just over 2,7 hours per week or 37 mins per day.

You also need to consider how well your soil holds on to water; if it’s sandy and the water runs through quickly, consider applying in small, more frequent doses.

Also consider that, ideally, the tree needs more water during flower initiation, fruit set and development – probably why God makes it rain in summer, where these trees are indigenous! – and holds it back when the trees are more dormant. So, if we apply that same methodology, it’ll probably work out well …

Bottom line is … do your MATHS! And make sure you’ve done it right .. there are many steps to trip you up.

And so it was that I was neatly bundled out the door so the retired couple could actually retire … albeit for only a few days … and I left wishing I’d had more time and appreciating, even more acutely, the immense value of people who have walked the earth (productively) for so long. May God bless you with many more years Roy, and may He allow us to learn all you know before you go.

Thank you for the privilege of learning and sharing.

AGRIULTURAL CONSULTANT: Roy Porritt

0825646270

In the next edition of TropicalBytes we have the incredible privilege of sitting with a grower/processor based in Kiepersol – a corporate affair – lead by a dynamic duo who have more energy and passion than most I’ve encountered thus far … can’t wait to bring it to you.