My very first Jaff-Avo visit! As you know, I try to “investigate” one crop at a time so that I can conduct an ‘intelligent’ interview. Imagine studying hieroglyphics without knowing enough about Egyptian culture or trying to write a paper on the intricacies of schizophrenia without having an education in psychology. Well, I pay the same respect to our platform by wanting to know as much as I can about a crop before attempting a Jaff story. But we all have to start somewhere and here I am, on the start line … before you write this story off though, take this into consideration:

- Nervousness hones the senses. Yes, I was incredibly nervous going in to this interview. Not only was I new to Avos, I was in a strange province and in someone else’s space, humbly asking them to not only teach me but to help me teach YOU, a diverse profile of farmers who may know a LOT or a LITTLE. This anxiety made me EXTRA SHARP and sensitive to every pearl of wisdom dropped.

- The planning behind the planning. I’m one of those who plans the planning. The devil’s in the detail so I shake it all out passionately. What this means, in practical terms, is that I did the homework necessary to be able to present myself at the start line.

- The best Jaff(s) to start with. These two Jaffs embraced my ignorance and happily padded their interview with all the background and foundation necessary to empower my understanding which has translated into (what I believe is) an awesome story with many highlights ready to improve your operation.

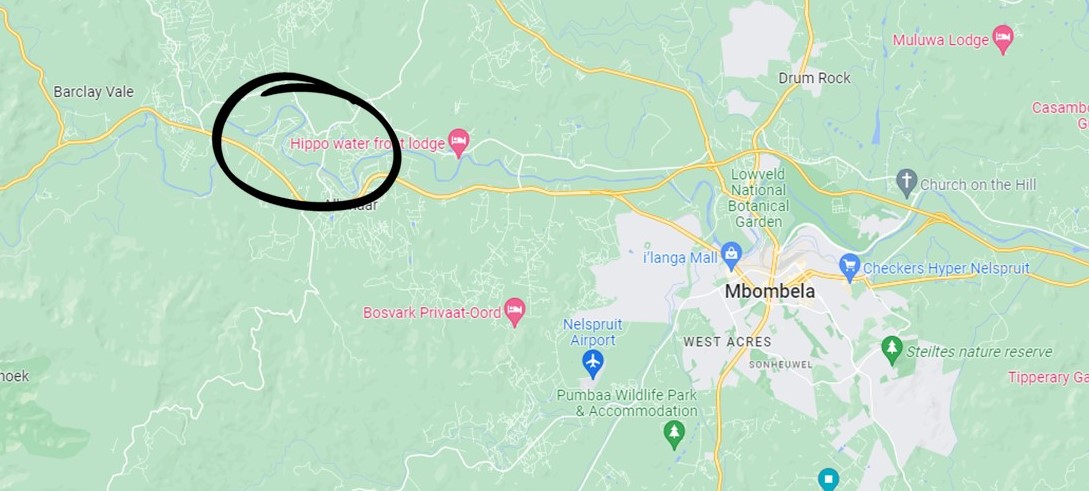

This Jaff duo is the perfect partnership; Owner Jaff started his working life as an electrician but harboured a yearning for farming while he built the capital to fulfil his dream. Then, in 2005 he was finally able to do that when this spectacular piece of land came on the market. It’s proudly placed in a fertile bulge of the Crocodile River, only a few kilometres from the city of Mbombela. It was growing avos, mangoes and citrus when he bought. Owner Jaff has made some changes over the ensuing years, but overall, this continues to be a solid success story, proving that you don’t have to inherent a farm to make a go of this incredible career.

About 4 years ago, Owner Jaff was approached by a young man who also longed to farm but, similarly, hadn’t been born into it. He was studying accounting when he decided to follow his heart. Having a connection to Owner Jaff, he asked whether he could spend some time on the farm to see whether it was indeed his passion. It didn’t take long to confirm that agriculture was most certainly his destiny. And the Accounting wasn’t wasted; he has been able to bring his financial skills to the table and deliver immense value in budgeting, cash flows, forecasts and planning. Not only has his farming knowledge grown under Owner Jaff’s tutorship, he has become a vital part of this operation, fulfilling roles that don’t come naturally to Owner Jaff. Jaff’s background in accounting gave him an invaluable perspective to farming; he said Accounting offers no latitude for creativity, innovation or experimentation whereas, in farming, there are 50 ways to do something and all could be argued to be right for the situation concerned. It’s far more stimulating for his curious mind. It’s also constantly changing so today’s solution might need to be rethought tomorrow.

And so it is that Apprentice Jaff is now our official Jaff for this story, freeing up Owner Jaff for far more important jobs … like fishing … he has to consistently hone his skills just in case he’s ever called on to fish for our country again … yes! Owner Jaff was a Protea Angler. 🐟 Neglecting that kind of talent would be sinful!

So let’s get into the farming details:

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 6 September 2022 |

| Area | Mbombela (Nelspruit) |

| Extent | 110 hectares, of which only 68 hectares are cultivated; 24 hectares to macadamias, 1 hectare citrus and 43 hectares of avos. |

| Soils | Very fertile due to the ox bow of the river – 70% deep, red Huttons. |

| Rainfall | 800 to 1100mm annually |

| Altitude | 730m above sea level |

| Distance from the coast | 200kms |

| Temperature range | Av 26° to 28° (annual average). It’s the extremes that do the damage; Heat up to 42°, with wind, in Nov. Cold down to -6°.

Avos prefer 7° to 26°. |

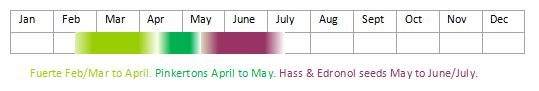

| Varieties | Fuerte, Hass, Pinkerton and a few seed varieties. |

This farm is located on the banks of the spectacular Crocodile River

WHICH CROP TO COVER

It was a dilemma, on this farm; do we cover macs or do we cover avos? Owner-Jaff said macs. Jaff said avos. The former’s reasoning was based on the current state of the avo market and the fact that he wasn’t feeling like a particularly successful farmer, having PAID IN on the avo crop this year. “And we were lucky because some of our fuertes, harvested early in the season (end Feb) and sold on the local market, fetched a better price,” adds Owner-Jaff. He explains that they didn’t have any Pinkertons this year, which ended up being a good thing because they probably would have had to pay in on them if they had been exported. They did have some Hass though – which was taken to market and they (this farm) were invoiced for it 😧.

Owner-Jaff also felt that, because they are phasing out of avos, he wasn’t a great advocate for the crop. But, we decided to do avos anyway because these Jaffs have learnt some invaluable lessons over the years and I was keen to bring you insights from a farmer who is moving out of the crop … sometimes knowing when to quit is priceless.

DIVERSIFICATION

This farm has walked a journey trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t. The major factor impacting viability is weather extremes particularly over the last 3 years – one November the extreme heat caused all the trees to prematurely drop their fruit. The following year was very cold, bringing lots of black frost, which damaged the fruit and killed many trees. Last year saw similarly cold weather that plummeted the gauges below zero; the worst affected were the macadamias and they lost the entire crop on 10 hectares. The affected trees were 6 years old. 30 hectares of avos were also destroyed by black frost – mostly the Pinkertons.

The morning after the black frost – the crop and many trees were lost in the freeze.

Four years after Owner Jaff bought the farm they removed all the citrus in favour of more avos. In 2015 they removed the mangoes and planted macadamias. The avos were doing well but recent price drops have changed all that. That, and the susceptibility to heat extremes and water-borne fungi. “You can’t insure for cold damage so we need to plant something that can handle the cold. Citrus did well here before and can handle cold so we’re going to try that again,” says Owner Jaff.

The plan is to max out with 40 hectares of citrus, 30 hectares macadamias and a 5-hectare block of seed avos. When producing this seed, insect damage, hail damage, sun burn, exterior fruit conditions and international market forces have little impact on the product price making it a viable option for this farm.

Jaff will grow the citrus in the coldest parts of the farm. They’ve chosen ‘Midnights’ which is a hard-skinned navel variety that realises consistent and stable prices. The macs will be nurtured in the more temperate areas. Jaff has just bought into the new mac-processing facility right on his doorstep, in fact, I think he could stand in his orchards and throw the nuts into their bins if he tried. 🤣

Last year these macs were hit by frost. The flowers were just coming out, way before the stage we see here. After the cold, all the flowers fell and there was no repeat flowering that year. Jaff says this is a Beaumont but it was quite atypical in that the flowers were not pink nor were the leaves terribly spiney.

Back to Avos …

SELECTING CULTIVARS

Jaff recommends you chose cultivars based on what the markets are buying even though the trees have a 40-year tenure and trends are likely to change. They have 44-year-old Hass trees, planted in 1978, that are still producing well but, lately, they are starting to give signs of age with smaller, less uniform fruit.

Whilst in France this year, Jaff visited some of the grocery stores that their packer supplies and saw the Halls boxes there – all Hass avocados. This European market has always preferred Hass because they can see when it’s ripe. The green-skinned varieties tend to cause confusion over when it’s ripe – this results in so much being wasted.

“There’s about a 4,5 to 5 year waiting list for avo plants from top nurseries,” explains Jaff, “they’re all clonal rootstock now which is necessary for consistency.” He says you should only deal with accredited nurseries and, even then, take an active interest in your trees. Jaff says you can do this by taking leaf samples from your order and have them tested to make sure all the right nutrients are present and the trees are in perfect condition before you take delivery. You can also ask for the testing proof that the roots are free of any harmful pathogens.

The biggest concern in avos is ASBV (Avocado Sun Blotch Virus) which is a farm-killer and not always visually evident – more info under DISEASES below.

Here are the things you should look out for when viewing your trees in the nursery:

- A 6-litre bag (minimum) to allow space for good root development.

- Uniform root development (from top to the bottom of the bag).

- Well-branched root system with white root tips.

- No mechanical, chemical or insect damage anywhere.

- Straight stems with smooth graft unions.

- Graft union should be between 5 and 40cm above the soil/growth medium surface level.

- Stem thickness, at soil level, should be at least 8mm.

- Branches no lower than 30cm from the soil.

- Evidence of at least 2 hardened off leaf flushes.

- A minimum of 10 fully grown leaves on the tree.

- Glossy, dark green leaves free of deformities, discolourations or signs of malnutrition.

- Proof that the seed source material was tested for ASBV within the last 2 years.

- Proof that the scion material has been tested for ASBV in the last 3 years.

LAND PREP

On this farm they rip and cross rip to a depth of at least 1,5m before pushing ridges. The beautiful, fertile, rich, red huttons are the envy of any agriculturist. Jaff says they don’t risk pulling up anything other than goodness by going so deep and this ‘new’ soil supplements the ‘used’ soil on top. The ridges are built up to 1m high and 1,5m wide at the top. Jaff says “The higher the better but this is limited by your land prep budget.”

If their soil is so great, AND so deep, why do they ridge? Jaff responds; “We have high water tables on this farm, so that’s one reason. We also like to avoid any possibility of compacting the root zone and ridges minimise the chance of this happening. Loose ridges are vital for root movement, aeration and water movement.”

When it comes to deciding which way to run the ridges, Jaff is not convinced that the direction of rows makes a huge difference and mentions a few other factors that impact outcomes to a greater degree; “For me, it’s more important that as many of the rows run in the same direction as possible as this makes a big difference to tractor efficiencies. Another element is the slope and how ridges affect water flow.” This farm is very flat with a gentle slope that is held together by vegetation and well-placed waterways. Jaff encourages farmers to start planting vegetation, that will prevent erosion, immediately after land prep is complete.

When it comes to spacing Jaff says that this is dependent on management capacities, cultivar concerned (both canopy and rootstock) as well as pruning preferences. When it comes to avos, the growth habits can be vastly different, as illustrated below:

Different growth patterns: Seed avocados on the left and Hass on the right. (But look at the flowering on that Hass!!)

So, while Hass orchards would have lower densities, seed avos can be planted closer together.

On this farm, the average spacing is 7m x 4m but they find they can manage 7m x 3m for upright growers. There is a block here, planted in 1978, that is 12m x 12m and yet another, established in 1982, planted at 8m x 8m so the trend toward denser orchards is clear.

Ordinarily Jaff would put irrigation in before the trees are planted but, because cash flow is a priority right now (as they focus on establishing the citrus), they will use a water cart for a year and then put irrigation in.

PLANTING

Jaff places markers in the centre of the ridges. When the labour comes through to dig the holes, they use a steel template which is placed over the marker. The hole is dug to a set size (about 30cm square) and 40cm deep. This template is used again to make sure that the tree is planted exactly in the centre of the hole.

When irrigation has been installed before trees are planted, they put a slow release into the holes, with the young trees. If there’s no irrigation (and they using a water cart) then they put the fertiliser on top. Either way this keeps the trees fed for a few months.

As the soil is being filled in around the roots, water is used to remove all the air pockets. They continuously add soil and settle it with water, add more soil and wash out all the air, add soil etc etc until the top. “You cannot fill above the bag soil line EVER!” emphasises Jaff, “If you do, you run a high risk of phytophthora taking hold. We show the labour to use the nursery tag as a marker.” He then adds that it is also important that the roots are not left too high above the soil as exposure brings its own set of challenges.

Because there are so many things that could go wrong in this vital phase, Jaff is in-field all the time during planting, constantly checking, “This is one area where you cannot afford to make a mistake,” he says, “and it’s worth investing yourself especially when you consider what we expect from these trees for the next 30+ years.”

Note the nursery tag which guides the workers on where the soil should level up to. The nursery releases the trees with painted stems and Jaff will add more paint (white PVA with copper) if the tree is scarce on leaves. You can also see the compost mulch around the base and the micro irrigation.

This farm had a gigantic 30m wide x 10m deep “donga” (hole) on the farm. In the first year of Covid, they used the time constructively to move 1000 ten-tonne truckloads of landfill from the new Macadamia processing plant to fill it in and now have an additional 6 hectares of arable land. It’s only right that macs are planted here and that’s about to be done – Nelmak 2s start their new life, in this soil, next week.

Ridging and markers

Out of interest, Jaff will be imitating something he saw in New Zealand when it comes to securing this new orchard; he’s planting casuarinas, 1m apart, to create a human, animal, visual and chemical barrier around this new mac orchard. As these grow (to about 50cm diameter) and have side branches, they will create an impenetrable barricade.

YOUNG TREES

Jaff stakes all young trees. The plastic stake, from the nursery, is removed when the tree is planted and replaced with a timber pole tied with sisal string in the shape of an infinity sign. “Make sure this is very loose,” warns Jaff, so that the tree is not strangled at all.” He goes on to emphasise that weekly maintenance is imperative to check that all the trees are secure. “Avo trees tend to flush heavily; often becoming too heavy for their little stems,” warns Jaff. To minimise the risk of breaking, Jaff cuts weight off the canopy of young trees, 3 or 4 times, until the stem and roots are strong enough to hold the vegetative growth. Each tree is individually assessed and the stake is kept as long as required. At this point Jaff points out a key differentiator between avo and mac farming; “Terwyl macs blok-boerdery is, is Avos boom-boerdery.” Translated (for our international readers) this means that, with macs, you can farm per block but, with avos, you have to farm each tree individually. “They’re hard-work,” Jaff sighs.

Trees are staked at an angle so that the stake (which is shaken around in the wind) does not damage roots or create a hole in the root zone. It is loosely attached with this degenerating sisal that will not damage the tree but needs to be replaced periodically.

Much like an ultra-marathon, most of the work has been done by the time you get to the start line.

TOP-WORKING VS REPLANTING

Often I encounter a situation where a farmer has had to make a choice between replanting an orchard, or top-working it. And I wish I could give you clear guidance on which option is best but there are just way too many factors impacting the decision. Here, Jaff has decided to top-work a Fuerte orchard that was badly hit by black frost. He made a fundamental decision to change cultivar from eating-avos to a specific seed-avo that will be used for root stock by a national nursery. Because many of the trees in this orchard died after the frost, he had to gap plant and had a nice comparison to show us:

Tree on the right was planted 2 years ago. Tree on the left was grafted 2 years ago – note the remarkable difference in size and flowering. Jaff has no regrets about top-working.

The next question is which top-working technique to use. The most common is to pencil graft; like they do in nurseries, on new trees. But the alternate; block-grafting, seems to produce a far better result. This was illustrated on macs in this story: https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2021-07_jaff_17/ and now again, this time in avos, it’s proving to be a winner.

The nursery did lots of testing here, with various types of grafting. Block grafts have shown great success. This tree is now on Bounty root stock with Fuerte in the middle and Seed Cultivar bearing wood.

The pencil grafts have also worked, as shown here on this two-year old work.

Jaff points out that hygiene and sanitation is incredibly important when grafting avos.

Good use was made of the wood when the mature trees were prepped for top-working.

WATER

This is a topic on which Jaff has learnt a lot – the fact that there’s no shortage of it on this farm is one of the biggest reasons. Yup – you guessed it – they were over-irrigating … since putting in probes they’ve had further insight and been able to regulate more successfully. These are Jaff’s irrigation pearls:

- The only phenological phase that really needs supplementary water is flowering. Jaff says there is actually a dry-land avo farm, about 5kms away, that is doing really well. Their success inspired him to examine his set up more closely. Whilst dry-land is possible Jaff would hesitate as he really believes in the value of sufficient water in the sensitive flowering stage.

- “Rather farm avos too dry than too wet,” says Jaff. He carries his manual drill (auger) with him at all times and is always testing the soil, checking for water logged soils that will bring far more grief than dry soil. Phytophthora thrives in anaerobic (water-logged) environments. (This sound advice applies as much to macs as it does to avos)

Jaff brought an interesting perspective when he commented how he believes that we can thank corporate farming accountants for many of our learnings in irrigation management. “I believe it was their questioning of every line on the expenditure statement that raised questions around optimal irrigation. By asking where and how costs could be cut and trying to establish the lowest investment for the most return, the industry has learnt how little we can irrigate without compromising the crop. In fact, the opposite has happened; farming these trees has become better since cutting back on irrigation,” says Jaff, “Traditionally, farmers have irrigated all year round believing that you can’t over-irrigate. Corporates have questioned that.”

This farm runs on micro-irrigation. The small trees get 3 litres per hour for 2 hours per week if there’s no rain. If the temperature goes into either hot or cold extremes he pushes up the pressure for 30 mins to an hour to either cool or warm the orchards, as required. Wait – what?

I’m sure there are some farmers for whom that makes sense but, for the rest of us, here’s some clarity:

- In excessively high temperatures (this is the easy one) the fine mist emitted by the high-pressure micros humidify and cool the orchard micro-climate. I have heard many farmers disagree that this is even possible but this Jaff believes it has helped reduce orchard stress.

- In excessively cold temperatures Jaff uses the mist to ‘coat’ the leaves in ice. Because fluids freeze at 0°C Jaff can use the ice to handbrake the temperature dive experienced by the leaves. Once the ice has frozen (white frost), it doesn’t get any colder; the temperature experienced by the leaves, doesn’t go below 0° In the absence of this moisture, the air around the leaves can continue to get colder and colder, way below 0°C, and the plant cells are destroyed when they literally burst from the cold. This is black frost. So, they irrigate the air, not the plants.

Ice jackets.

Jaff says knowing when to spray is the challenge and he bounces around like a nervous chihuahua (his words 🤣) when temperatures start to drop. Besides the irrigation, he employs a second tactic to combat the killer cold; FIRE. Yup, he literally lights bonfires in the orchards. Numerous pyres of old tyres, primed with dry grass, are burnt to generate enough smoke to create a ceiling. Well, that’s the plan … Jaff says he thinks this strategy works better in theory than it does in practice but it’s better than doing nothing.

Jaff’s ‘candle in the cold-room’. The passion this man has for farming needed no more evidence than this.

The theory is that because they’re in a valley, the smoke from the fires hits the inversion layer (where heavier, colder air, below meets the lighter, warmer air above) and forms a type of ceiling/blanket which will trap the warm air, generated by the fires and the irrigation, and, in this micro-climate, temperatures won’t go below 0°C. “I do suspect my efforts may be ineffective, like trying to warm a cold room with a candle, but if there’s the slightest chance that I avoid some loss, it’s worth it,” smiles Jaff.

By examining the post-freeze damage Jaff has learnt that the trees are very good at creating their own micro-climates thereby preserving a lot of their inner canopy leaves. The problem is that avos flower on the outside so an unfortunately timed black frost will destroy an entire crop.

Black frosted avos the morning after.

Before and after … answers the question as to why it’s called ‘black’ frost.

A farm in the same valley has tried some other climate control strategies; one being netting the orchards. In winter they placed enormous fans and gas heaters to blow warm air into the trees but, instead, the cold air got in and they lost the entire orchard, not just the flowers and outside leaves, like on Jaff’s farm – the whole tree died. This farm is now replanting the entire farm, for the third time; this time with citrus, all still under net but the fans are gone.

Apart from being a tool in temperature regulation tactics, micros are preferred by Jaff because he can confirm everything is working with a quick visual check. He runs a small farm with a lean team and needs to be able to check up, easily and quickly, on the fly. With drip, it wouldn’t be as simple. If they weren’t on the river and if they had to pay for power, he would probably choose drip for a whole different set of reasons.

Got your attention again hey? “What do you mean he doesn’t pay for power?” I hear you ask. Hell, some of you are more intrigued by where on earth he GOT power (thanks Eskom), regardless of whether he’s paying for it or not.

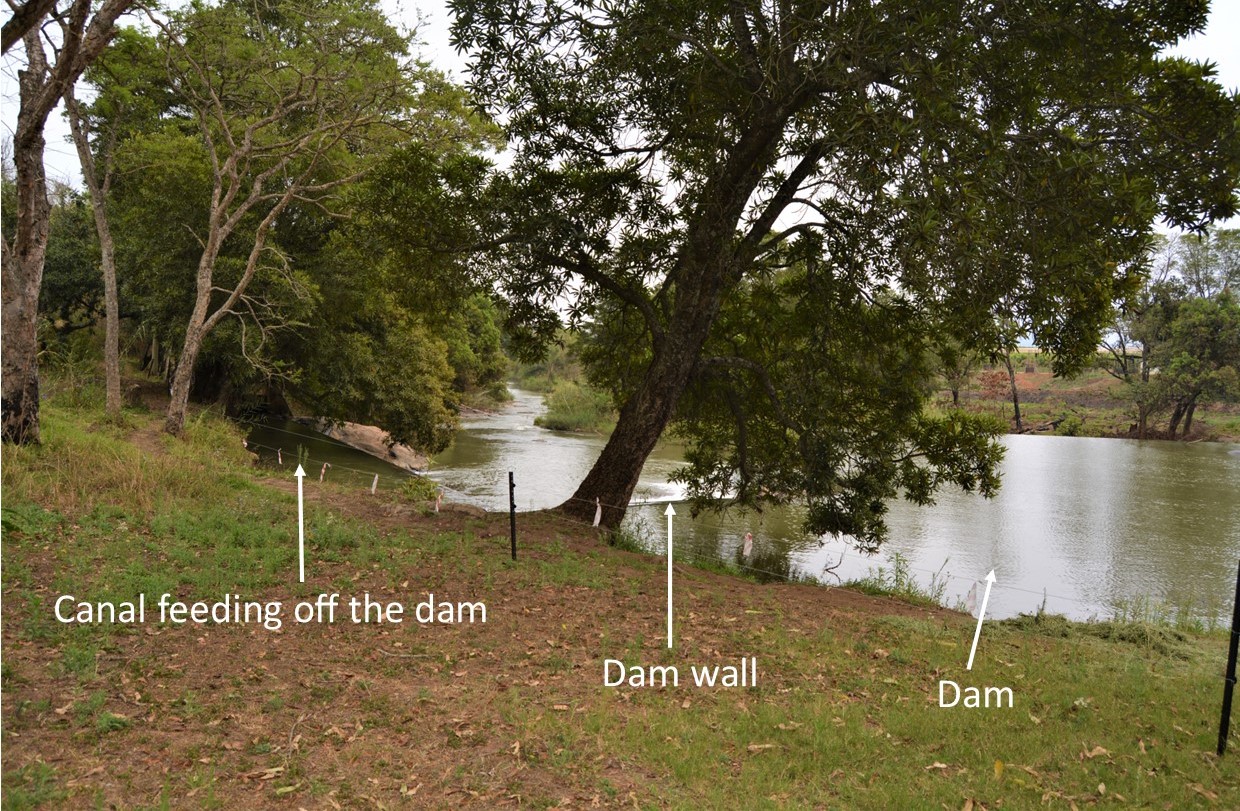

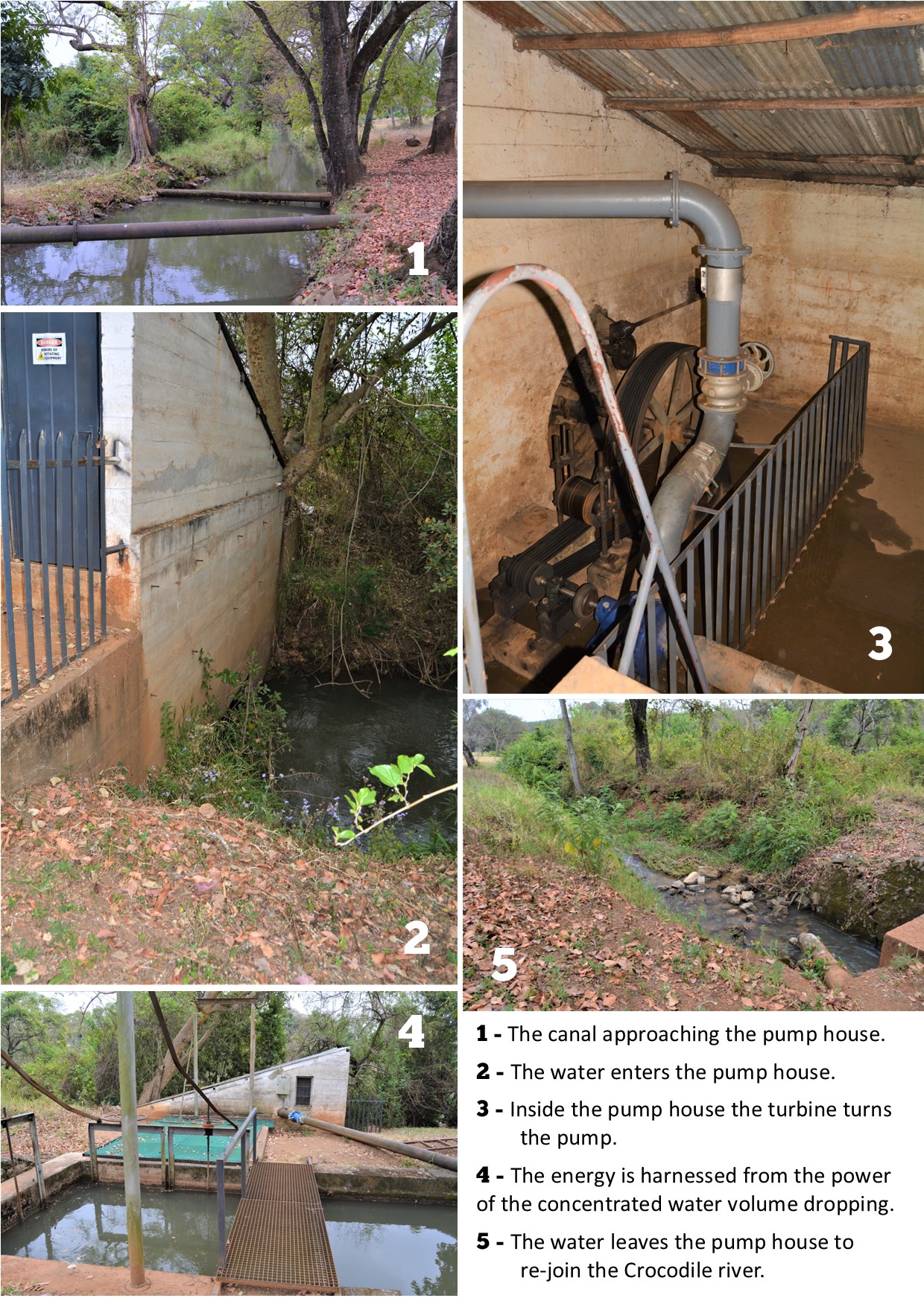

This farm is privileged to have a turbine unit in the river that powers the pumps delivering the irrigation. As the Crocodile River is always flowing, the power is always there.

And this is the real competitive advantage of this farm. I’m not sure our foreign readers will fully appreciate the value of this but it is indeed profound; as Eskom (our national power service) rots and seems close to imploding on itself.

60 years ago this was a government-owned experimental farm and they installed the power-generation system as one of their research and experimentation projects. There is a weir in the Crocodile River directing some flow into a canal and to the plant. In the plant, the falling water turns the turbine which turns the wheel that is linked to the pump with fan belts. The pumps require 55kW to run and are adjustable to regulate pressure. This system provides a savings of about R30k per month but, more importantly, it delivers consistent power and is therefore far more valuable than the R30k it saves. When budget allows Jaff will add batteries to the system so that the additional power created can be stored and used for other farming activities.

Start of the power generation operation

Here’s what it all looks like in a flood … unless they move the equipment in time, it’s an expensive experience.

As mentioned, Jaff focusses more on making sure the farm is not over-irrigated and uses probes to help him monitor the subsoil conditions. There is one probe per soil grouping i.e.: he watches the patch of sandy soil with one, the patch of red with another. Jaff warns that farmers don’t allow technology to make them lazy, “Never stop checking with the drill (auger) regardless of what the probes are telling you. Rather use them to improve your farming, not make your life easier.”

When this farm has needed cash flow they’ve sold a few probes, but were able to continue, unphased, because Jaff had learnt from the probes and was able to carry on without them. They farm the avos a little drier than the macs, especially during flowering when Jaff believes the macs need a lot of water but he is extremely cautious about overwatering the avos, especially with the prevalence of phytophthora in this water. He has seen a very positive result from farming like this, on both crops.

Crocodile River in flood and Jaff’s trees under water.

PEST MANAGEMENT

Shall we start from biggest to smallest? And I’ll bet that Jaff’s is bigger than yours! This farm has a hippo problem – not sure how many of you can say that? While they don’t intentionally damage the trees they tend to be a little cranky with the staff.

There are 28 hippos that consider this farm their turf. Obviously, these Jaffs are nature-lovers but there’s a compromise somewhere between no hippos and 28 hippos … so, Parks Board is helping them relocate a few. 11 have gone already and they hope to move another 10 or so, to make space for babies before they need to come back and move more. Unfortunately, some have had to be shot because they were not being reasonable eg: a young bull was put down the Friday before I was here because he was dangerously close and a little “unstable” – he had obviously been on the losing end of a few testosterone-fuelled challenges, as can be seen by his wounds.

The torturously injured young bull who had lost his regard for humans.

Parks Board issued a permit and Jaff-mentor put him out of his pain. Another one that was shot had been tormenting and chasing the staff for 2 months before Jaff-mentor finally got a permit to have him removed. It was hard for Jaff but he didn’t want to have regrets about losing a team member or one of the farm children. The animal becomes dangerous when he is no longer afraid and he doesn’t move off when approached.

A hefty footprint in the orchard.

A capture pen has been erected on the river bank. It is primed with food and then the Parks Board officials wait until there are a fair number (at least 5) in the pen at the same time and then they close it. This can take weeks, as the animals are suspicious, especially after a capture. The 11 they have already caught were mostly bulls – almost all of a good size and young. There are some rowdy bulls further down the river and Jaff says that, once enough have been caught up here, those ones will move up and the herd will be stabalised. They enjoy the dam/weir that serves the power generation plant.

Electrified wire to ‘guide’ the hippos towards the capture pen.

How to catch a hippo

Hippos in the Crocodile River. Jaff says healthy hippos are not very dangerous – they will keep their distance and stay in the river during the day. When they find a hippo in the orchards that does not retreat when the people approach, it’s a bad sign, they know there is something wrong and he’s probably sick or hurt.

No swimming at this picnic/braai area – but it’s still one of Jaff’s favourite spots on the farm.

On to smaller challenges …

To set context on Jaff’s approach to pest management, his priority is to achieve maximum effect with minimum cost (financially and environmentally). Complicating the task is crop diversification which means that Jaff often has to spray the whole farm to avoid chasing pockets of insects that move between crops. Thrips is one pest in point. Thrips damage on mac husks is tolerable but, on avos, it’s expensive, “The flush on the macs is the factory for the next crop,” explains Jaff, “and the young fruit on an avo tree can be significantly damaged by thrips.” The problem is that, even after the thrips have stopped nibbling on the fruit, the scar continues to grow right through to maturity and results in a lower grade product. Because of this, Jaff focuses on control during flower stage so that, by the time the young fruit is present, the impact is minimised. Jaff uses products with the active ingredient of spinetoram or abamectin, both of which require contact.

Supporting his environmentally-sensitive approach, Jaff limits the use of preventative chemicals opting instead for contact chemicals. Even though the consultants provide an annual spray programme, Jaff supersedes this with intense scouting. He believes this serves both his financial and environmental goals.

The scouts set out every Monday and Thursday, at sunrise – it’s a visual scout (with no chemicals) as opposed to a knock down scout (with chemicals, sheets and ‘counting the dead’). The scouts scour 10 individual trees per block and report sightings. Every second Wednesday Jaff creates 3 stations per block, each with 3 trees (total 9 trees per block) and does a knock down spray.

Based on these results and the phenological phase of the tree (flowering, setting, mature fruit etc) Jaff will decide whether or not to do the programmed spray. eg: thrips are a concern when fruit is very small but not when there is no or mature fruit. When fruit is mature, stink bug control is important.

Jaff also has a measured approach to control and tolerates a level of each insect, eg: If he finds stinkbugs on 3 out of 10 trees and at least 4 bugs per tree, that’s 12 in total for the block … then he considers taking action but he wouldn’t for only 4 bugs, opting instead to monitor closely to see if numbers reach the (in)tolerance level. He uses his gut to decide when there are too many and the likelihood of there being males and females and therefore eggs is just too much of a risk – he runs this against the cost of a spray.

There is a plethora of diversity in Jaff’s orchards and his extensive library of photos proves his appreciation.

Jaff adds, “When you spray make sure the sprayers are calibrated. Spray the right amounts for the infestation. I spray 2500l/hectare early in the season and 4000l/hectare in mid-season so that the control is proportionate to the problem.” Jaff explains that there are many opportunities for calibration to fall out. He has 4 tractors and 3 spray carts but cannot ‘mix and match’ tractors and trailers because that affects calibration. i.e.: he makes sure the same tractor always pulls the same spray cart as the speed it travels, in every gear, is calibrated to the trailer.

The tractor drivers are also well-schooled in why their speed is important. Jaff is always present when they spray and it is always done at night (he’s BEEing considerate 😊). Of course, that’s prime hippo time too so Jaff drives around in the bakkie (rather than on the motorbike) and monitors the tractor speed; makes sure no rows are being skipped and then, at the end of the night, he checks that no one has over or under sprayed (chemical surplus or shortage). Through this meticulous management he has found the sweet spot which is now easier to manage and only requires his ‘presence’.

Between the macs and the avos it seems Jaff is kept on his toes by almost every pest alive … Fruit flies leaves a cross scar on the skin. Coconut bug and stink bug stings leave an indent. Avo bug bites present as a series of spots. Almost always a sting will create a wound from which sugars will leak (white crystals).

Because this farm has chosen to carry some stringent registrations (Global Gap 2.0, SIZA, Rainforest Alliance) pest control is a very important facet of the business in terms of chemical choice and withholding periods. Weighing this against budgets and producing big quantities of good quality fruit for export is a challenge.

Jaff feels both the rock and the hard place – wanting to embrace IPM (Integrated Pest Management) and having a decent export crop – so he tries to do what he can for both. He has planted a lot of bamboo around the farm as it is a great refuge and host plant for lady bugs who enjoy a good thrips feast whenever they can get it.

Beehives and ladybird sanctuary (bamboo) in the same neighbourhood.

Jaff gets his pruning guys to spend time with the scouting guys so that they are equipped to identify issues while they’re pruning. If small, “contained” outbreaks are identified, he immediately goes and sprays the infested area in an effort to contain the outbreak and prevent a farm-wide spray. Despite this they do end up spraying around every 4 weeks because of the insect cycle, but it’s not exact.

It’s all about finding the sweet spot between where nature wants to be and where profitable faming lies.

Fruit setting on the seed avos – this is the stage at which the fruit is most susceptible to thrips damage. Although the thrips only has less than 1cm to damage now, the scarring grows with the fruit and will end up extending the full length of the fruit. Luckily it’s not an issue with seed avos.

Cleaning and get ready for the spray tonight

DISEASES

Avocados are highly susceptible to fungi and require focussed attention to each individual tree to monitor the status and prevent spread.

- Phytophthora: Jaff says that the Crocodile is the most highly phytophthora-infested river in South Africa. He deals with this disease through water management (keep soil aerated; avoid saturation). Jaff says there are fungicides you can apply but it’s pretty pointless if the water he uses to irrigate is the problem. He chooses instead to make sure his soils are on the dry-side which keeps the phytophthora in check.

- ASBV (Avocado Sun Blotch virus) – this is a virus I haven’t encountered in any of the crops we’ve covered thus far; it’s silent, swift and deadly, necessitating extreme action to control it; if even one branch on a tree has it, the whole tree and its orchard neighbours must be cut out, cut up and burnt. The ground they were in must be turned and left fallow for 18 months.

- Cercospora: Fuertes have a greater susceptibility to this fungal infection which leaves small black spots all over the skin. Jaff says that his hawker market (informal traders) prefer the avos with spots on which, although strange, suits him well as he doesn’t have to be too concerned about controlling it. The export market is not as tolerant though so they do use copper sprays as required. It is prevalent in the damp, rainy season – Oct, Nov, Dec – and Jaff will typically do 3 sprays over this time period; 3,5 l/hectare applied with a fan sprayer. “The fruit must be completely sodden,” advises Jaff, “and this often requires a second spray with hand guns, especially in the denser orchards.” They also spray the dark-skinned Hass avos if the season is particularly wet so they do not develop ‘pepper spots’.

Jaff sprays the fungicides at temperatures below 25 degrees because the ambient temperature affects the adjuvants he adds make sure the water is at the right pH. If it’s too hot, the leaves get burnt.

SOIL HEALTH

Jaff understands that soil health is the foundation of all farming, “You can’t farm if you don’t look after your soils.” He explains what he does in this department:

- Adding compost which is made from mac husks and avo pulp. When the seed avos are supplied to the nursery, they remove all the skin and flesh (all they need is the seed). The flesh is unripe so it has no commercial value. Jaff takes this back, sun dries it a bit, and then adds it to the compost pile. Orchard prunings are also chipped up and added. Cattle manure, or similar animal waste is added as well. Every 3 years they supplement the orchards with this compost. This is done with a tractor, trailer and TLB. The team will go through the orchard, scraping some surface layer away, checking the root presence and health, spreading the compost and resettling the area. Alternate sides of the tree are done each time.

- Jaff has stopped all herbiciding on the farm except for the ridges in young orchards. As mentioned, the hippos graze the orchards and, if there is tasty greenery on the ridges, they will inadvertently damage the young trees. Everywhere else, vegetation is controlled mechanically with mowers and brush cutters. “Cutting herbicides from the programme has helped reduce expenditure,” smiles Jaff.

- Abundant vegetation in the orchard is advantageous to both soils and general orchard health as it helps to regulate temperatures in the ridges and provides a haven for diverse insect life. Because he wants richly diverse insect life, he purposely encourages a range of vegetation. Unlike macs where the harvest method demands a measure of orchard clean up, avo orchards can remain ‘over-grown’ throughout the season.

- To gain an understanding of the soil profile and overall health; Jaff will periodically dig a 1,5m hole in an orchard. He notes the soil composition through the layers, root system (health & depth), moisture content and flow, and whether there are any ‘floors/blockages’. He then takes corrective action to address any issues if required.

- Mulching; Avos make their own mulch by dropping leaves constantly and Jaff adds to this by using an off-centre mower every now and again, when growth gets out of control. This mower discharges the cuttings under the trees, adding an extra layer of nutritious mulch.

Two-year-old Hass orchard with interspersed Seed Cultivars. Ridges are kept clear of growth to discourage hippos getting close to the trees and causing damage.

FERTILISING

Jaff supplements the various cultivars at different times of the year, based on their harvest times:

After harvest, Jaff leaves trees to ‘siesta’ for 2 to 3 months. This is a time of rest and recuperation where they don’t get any supplementary water or fertilisers. At the end of July/August they kick off the new season by putting a lot of water down, applying fertiliser one week later together with another hour of irrigation to soak that into the soil.

To decide what goes into the fertiliser, Jaff does leaf samples every year and soil samples every second year. “The soil environment is more stable than that within the tree – that’s why I do leaf samples more often,” says Jaff before I can ask the obvious. A specialist lab does the analysis and hands the results over to the fertiliser consultants who generate a programme – with almost every orchard block having a unique recipe. Based on this, Jaff orders the basics and decides what additional supplementation to add for specific objectives eg: fruit size is influenced by calcium (it builds cell strength) & potassium (influences water intake). Fruit size is a particular requirement on the seeds so Jaff will be sure to add these supplements to the avo seed blocks.

Jaff continues supplementing, according to the recommendation, and his own extras, up until the fruit is no longer affected by the supplements (oil accumulation stage – about 3 months before harvest).

Jaff doesn’t add microbes to the soil; but has used them to accelerate decomposition in the compost pile. Being in an ox bow of the Crocodile River, this farm’s soil is rich and healthy, proven by the fact that there is always an abundant supply of earthworms for Owner Jaff’s fishing expeditions.

When it comes to foliar sprays, Jaff applies boron during flowering, “this element helps the trees take up other nutrients,” says Jaff, “it is something that avos use a lot of and they can easily become deficient in this mineral.” Boron deficient trees develop knobs on the branches. “But don’t confuse this with a similar knob created by a certain insect,” he warns, “those are sharper whereas boron ones are blunt and round.” Jaff also applies boron to the soil.

In addition, calcium is also applied as a foliar feed; it helps with cell division and fruit set and is therefore applied when fruit is setting. Zinc and kelp are standard ingredients added to every foliar application on this farm; the latter being an excellent growth stimulator – Jaff likes to see it applied heavily enough that it drips off the leaves and supplements the root zone as well.

Gypsum & lime is required every 3 to 4 years to maintain a healthy pH.

“The biggest impact is made by the compost,” explains Jaff who typically puts down 35kgs compost per tree, “I saw this clearly when I wasn’t able to add compost to one Pinkerton block. The leaf colour and size in the orchard that got compost was way better that the block right next to it – also Pinkertons – where I had not been able to add compost. It’s the nitrogen in the compost that causes these visual differences.”

Like a macadamia, avo feeder roots are also shallow, making the top 30cm of the soil the ‘critical nutrient zone’. The root system extends under the entire canopy width and this is also why Jaff prefers micro irrigation as it services a broader area. Drip irrigated avo trees tend to have concentrated root zones that can become clogged and crowded around the drippers.

PRUNING

Up until a few years ago they were pruning avos similarly to macs on this farm; in the popular Christmas tree shape with a single central leader. Then they learnt about an alternate method, popular in Mexico. Jaff explains that avo trees bear on the outside of their canopy, unlike macs that are ‘inside bearers’. So, it stands to reason that, if you can maximise the surface area of the canopy, you will have more ‘factory’ in which to produce avos. The Mexican pruning method works with this theory and proposes that at least 3 leaders are created allowing sunlight into the middle of the tree.

Here you can see the beginnings of the multiple leader shape being developed where numerous stems are encouraged around an open “bowl” in the centre. As the tree grows, the leaders may change (through pruning) so that balance, maximum sunlight penetration as well as surface area is maintained.

Jaff’s been pruning this way for 3 years now and has had some great success as the trees are now bearing inside the ‘bowl’ as well. He explains the steps:

- Cut open in the middle by removing the central leader.

- Start encouraging at least 3 smaller trees off one tree (3 leaders with side branches)

- Remember to paint sunblock on the inside when you make cuts that will expose sensitive wood to the sun. Nutrients don’t flow through burnt phloem (layer of wood through which nutrients move). Fuerte & Hass are especially prone to sunburn as they have a tendency to ‘hang’ their leaves after winter. These leaves are dropped and replaced by new flush which often doesn’t provide the shade required to avoid damage.

Jaff has realised another benefit from this new method of pruning in that the fruit on the inside of the ‘bowl’ often escapes cold damage during those extreme temperature drops, “We have seen the benefits and will continue with this method of pruning the avos.” He adds that maintenance is a breeze because they come around once a year and clear the out the middle of the trees – preserving the multiple leader ‘bowl’ shape and any height that has gotten above tolerances. “Pruning has become far simpler since we adopted this method,” smiles Jaff, “and we have more time to spend on other jobs.”

Tree height is determined by harvesting. Guys go in with ladders so all fruit must all be within reach. The general rule is about 4m unless it is a nice easy tree to climb without causing any damage in which case it can get a bit taller. This ‘climbability’ is cultivar-dependant with the fuerte being the most suitable. Jaff calls them “boomhuis” (tree house) trees because they have lots of nice thick lateral branches perfect for supporting the structures built by little boys (and girls 😉). Hass, on the other hand, has more vertical, finger-like branches which are not nice to climb (or build tree houses in). All these branches, in a Hass tree, seem to want to grow taller than the one next to it before it pushes vegetation (and fruit). “It’s an ongoing job to keep bringing the branches down,” sighs Jaff.

HARVESTING

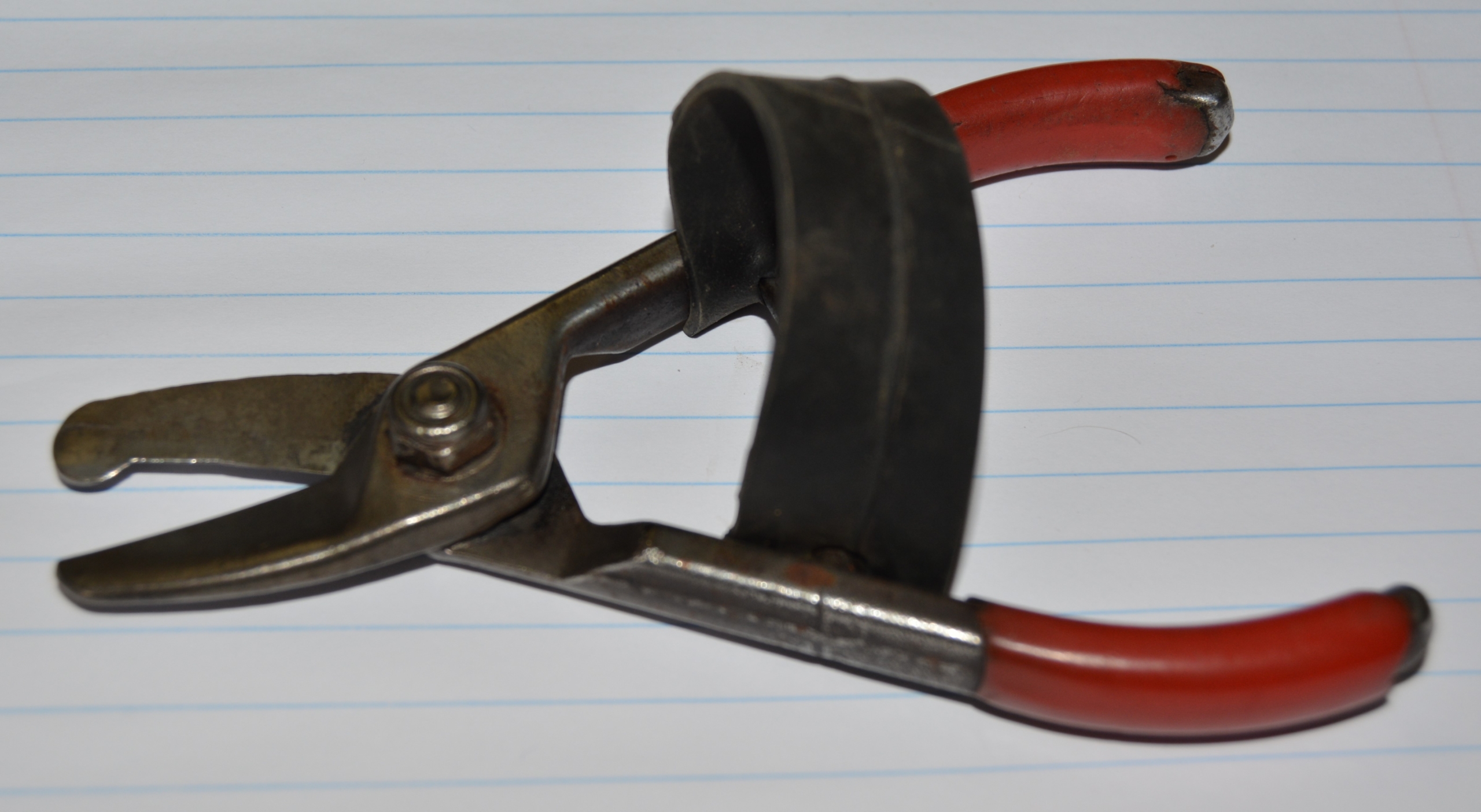

Every picker has a bag and a pair of scissors. Jaff says that you get scissors, fitted with GPS’s that send a report with every click which provides data on fruit concentration; an interesting insight, but here, they’re normal secateurs. Fruit is cut off rather than broken off at the stem because fungus will easily set in to the broken point causing stem end rot.

Harvesters take their bags (with a shoulders trap), secateurs and steppies (South African-ism for stepladder) and they pick and fill the bag up to a certain point. It is very important not to cause any damage to the avos when they are in the bag – which overfilling or excessive movement will do. The damage happens when the thin wax layer on the fruit is scrapped off. This allows leticil (fungus) to set in. The injuries are not immediately visible but will appear as black marks when the fruit is refrigerated. Marked fruit cannot be exported.

Minimising any fruit damage is so important that harvesters have nail inspection every morning before work starts (reminds me of boarding school 🤔).

Jaff and the tractor drivers, who move through the orchards with the pickers, carefully sort each bag poured into the trailer, while they’re in the field. Fuertes require an extra step in the harvest process; which is to dip their stem end in a fungicide to prevent stem end rot. Every single fruit is individually dipped.

Good fruit is covered with a shade cloth, in lugs, and sent to the pack house. Any damaged fruit is bagged and sold locally. This farm does have plans to turn a shed into a packing line that will be used for avos and/or citrus thereby saving on packing fees through a third party.

10 tonnes per hectare is the breakeven point at which this farm covers costs and has enough to farm for the next year. Jaff Owner has achieved 30t/ha off the Pinkertons in a previous year but the last 2 years here have been dismal; mostly due to weather extremes and export prices.

Profuse flowering on the Pinkertons. Good set as well.

Jaff explains more about the crop prediction; “The tree knows what it can hold and the excess is shed in November (dump). But, seeing a lot on the ground is not always a bad thing because, the more you see on the ground, the more is in the tree.”

You will notice the mature avos hanging with the flowers – these are last season’s late flowering and will be harvested in Oct/Nov as a little cash injection.

People from Halls, the packing house Jaff uses, come in once a week, during season, and do moisture tests on the fruit. Based on these results they advise when the fruit is mature and can be picked i.e.: when the moisture levels are right. Fuertes need to be under 97%, Pinkertons need to be under 75%, Hass is 81%. The fruit will only start ripening once picked and can be hung for a while enabling the farmer and packer to optimise profits through careful timing of release into the market.

MARKETING

In the final few seasons this farm will be developing their local market in an attempt to avoid meeting Peru head on on the international stage. Their Fuerte are perfect for this but the Pinkerton are a problem as they mature later and volumes are too much for local buyers – these will be going overseas.

The local market is made up of a few sectors:

- Jaff values his vibrant hawker trade. These people prefer green skins over the smaller, darker hass variety. Many come from Johannesburg and buy in 50kg bags; about 2 tonnes at a time. They hitch hike back to Jhb, with this load, on empty trucks.

- Roadside stalls are also good customers realising R20 per kg early in the season and R10 per kg later on.

- Locals: Fuerte & Pinkertons are packed into 3kg bags and sold directly off the farm.

“If you can get just one fruit, per bunch of flowers like this, through to maturity, you’re doing well” says Jaff. (These are Edronol seed)

FINANCES

Jaff shares my view that, at the end of the day, farming is a business (as is almost every activity we partake in, everyday). Businesses need to operate within budgets, use forecasts and maintain regular progress checks. Jaff’s Dad is a local accountant and handles the finances for the majority of farms in the area. He says that most farmers do not even do basic budgets much less work within them. Jaff, bolstered by his financial background, believes this is a major opportunity for all farmers to improve their operations.

The value that Jaff has brought to this farm is transformative; and quite possibly a major factor for its current success. He has instilled accounting principles to manage the operation as a business. During the interview I regularly heard him say “We’re just watching cash flow and will do this next year or the year after” – such wise management … or is it a matter of basic business sense? Simply managing what you have against what needs to be done to survive.

Many farmers have not been able to find the balance and simply buy when they have money; and don’t when there’s no money – there’s no plan or forecasting. And therein lies the demise of many high potential agricultural operations. Many farms in the area are being repossessed; land prices are usually around R600k per hectare but you can sometimes get it for R150k if the farm is in trouble and the owner needs to get out – a sad situation that might have been avoided with some judicial fiscal management.

Jaff knows that they’re on a very tight budget here but it’s all according to the plan, it doesn’t mean they’re unable to afford stuff, they’re just sticking to the plan. Diversification is a part of that plan; Jaff believes in at least 3 legs (avo, citrus and macs) so that, when one has a poor season, like avos did this year, there are 2 other crops to lean on. Jaff is managing the process of GRADUALLY replacing avos with citrus; hence the strict budget plan. He believes that sound financial management is THE SINGLE MOST IMPORTANT element determining the success of a farm. It affects everything, even relationships; eg; purchasing must be business, not relationship-based. Farmers can sometimes be loyal to the detriment of their businesses. They’re amazing people but business acumen is often lacking. Jaff says you need to find the sweet spot – be fair but don’t sacrifice the business for it.

CHEERIO

And on that sober note, it was time to take my leave – full of awe for the young, yet so wise and mature, Jaff I had just learnt so much from. And the incredible Owner Jaff whose passion, energy, enthusiasm and determination is the perfect yin to Jaff’s yan.

Thank you both for sharing your unique insights – I know there are many farmers who have grown through this encounter.

The blesbok blessed me as I drove out. Jaff explained that they fulfil 3 important roles on the farm; to graze (mow the orchards), add diversity and look pretty.

BIBLIOGRPHY

www.avocado.co.za (young tree assessment points)