Those of you who are regular readers have heard about Covid-Jaff, the very special farmer whom I (unintentionally and to my absolute horror) infected with Covid in December 2020, while doing his interview for TropicalBytes. He subsequently spent a considerable amount of time in hospital – including Christmas Day! – and even went in to ICU as a heart condition reared up. I was completely asymptomatic at the time of the visit and, to my knowledge, had not had any contact with an infected person. In the few days following my visit, my house of cards tumbled as my daughter’s friends started testing positive, followed shortly afterwards by her. But these teenagers are made of tough stuff and none of them were particularly sick. I had been so busy wrapping up the usual year-end demands from my other job and only started to realise I didn’t feel well a day or two after visiting Jaff. As soon as I got the positive result, I advised everyone I’d been in contact with, including Jaff. He was gracious from the beginning, saying that it wasn’t the end of the world if he got it – he was looking forward to getting it over and done with. He obviously expected an easier ride. Unfortunately, we had Version 2 of this dreaded virus and both got very sick. We stayed in touch and he continued to be so forgiving. The great news for all future Jaffs is that I am probably immune from carrying the virus, for the next few months at least!

I have just sent Jaff a text, checking that he is still getting stronger every day and, as always, he checked that I am too. Sometimes people take up special places in our hearts through the most unlikely circumstances.

And now it’s time to move on and learn farming from this amazing man from Ging …

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 8 December 2020 |

| Area | Gingindlovu, KwaZulu-Natal North Coast |

| Soils | TMS on hills and TMS boulder beds on the flats, near the river. Patches red dolorite and patches of middle ecca shale. |

| Rainfall | 950mm annual (lowest, 5 years ago, was 650mm – not enough to cope with the high temperatures and shallow soils) |

| Humidity | High |

| Winds | Typically coastal = rather high (especially the day I was there!) |

| Altitude | 43m to 128m |

| Distance from the coast | 8kms |

| Temperature range | Low 40s (up to 45°C at least once per year, usually in Jan / Feb) down to teens in winter. |

| Varieties | Beaumont, Nelmak 2, A4, A16, 814, 816, 842, 849, 863 |

| Hectares under mac | 138 hectares |

| Other crops | None (but they do have the nursery which does macs, avos and florist fillers) |

Farming is what this family has done forever; Jaff’s great grandfather started his career by settling on a farm in Gingindlovu in 1903. The subsequent generations continued, with the main crop being sugar cane.

Jaff is the youngest of 5 siblings. and he continues in the family custom of farming, with one substantial change – he has pulled out all the cane in favour of macs. The cane had been struggling for years under an antiquated irrigation system. Two years of drought and no available land to grow the scale of the operation meant that Jaff faced a big decision; does he continue to accept substandard returns from a crop he knows well or does he change direction completely. Typical of the farmers TropicalBytes interviews, Jaff was keen to go for gold and try something new but, to do it properly, he needed a lot of capital. Investors were the solution and have enabled Jaff to create the “race horse” he needed. Yes, it has meant he has had to share his farm but he remains motivated by his long-term vision.

From this Jaff, we will learn plenty about establishing a mac farm. His oldest trees are 4 years old and, even though the youngsters delivered 250% of what was estimated last season, it’s still early days. If you’re past the phase of establishment, this story is refreshing in terms of the interesting questions posed by this new mac farmer. If you’re still in the planting phase, it’s all relevant!

To cane farmers who prefer a more gradual diversification into macs, he advises that you resist the urge to give your worst cane lands to macs, thinking that, if it fails, you would have lost little. In reality, this strategy will risk much. He adds that some average cane lands can be decent mac lands and that you should rather choose what will be best for the macs, as the capital used to develop them is of greater value than the best farm land. Putting macs into better soils may mean the difference in yield of a tonne per hectare. At a conservative price of R100 per kg, that might be R100 000 per hectare …

Location of Jaff’s operation – KZN North Coast; Gingindlovu.

WATER, SOILS AND CLIMATE

This farm sits on the Amatikulu river so there is no shortage of water. The soils are a mix of Table Mountain Sandstone on the hills and Table Mountain boulder beds in the flats, near the river. There are also patches of red dolerite and middle ecca shale. As much of the soil is fairly shallow, he took an across the board decision to ridge all orchards thereby ensuring that all trees have a sufficient bed, regardless of the inherent soil depth. The ridges also ensure well-drained root zones, even in the valleys.

The Amatikulu river runs around this beautiful farm. The nursery sheds can be seen in the centre.

The farm is typically hot and humid and therefore perfect for macs. The only weather-related issue, confounding Jaff, usually happens in October/November. A few ‘hotter than normal’ and windy days followed by a significant drop in temperatures, together with rain, cause substantial nut drop. It’s different to the November Dump we’ve all come to anticipate as a phenological phenomenon because it happens straight after this particular weather pattern. The obvious deduction is that this weather change stresses the trees enough for them to readjust their loads. In trying to understand this and, more importantly, whether anything can be done to mitigate it, I went down the rabbit-hole labelled ETHYLENE.

Ethylene is a natural plant hormone that influences diverse processes in plant growth, development and stress responses throughout the plant’s life. Some of those stress triggers are drought, flooding, pathogen attack and high salinity. During flooding, for instance, ethylene induces the formation of aerenchyma tissue (consisting of air-filled cavities) for oxygenation. Ethylene is best known, however, for its essential role in the ripening of some fruits, such as tomatoes, bananas, pears and apples. Placing a ripe banana in a paper bag containing unripe avocados, for instance, will hasten ripening of the avocados due to the accumulation of ethylene produced by the banana.

As plant production of ethylene has been associated with fruit abscission after stress events, when faced with a mac tree that is dropping its nuts prematurely because it is stressed unnecessarily, we must surely consider whether we could adjust ethylene levels but, with such an important and multi-functional hormone, ‘fiddling’ with it can be dangerous. Can we possibly limit the stress catalysts? eg: climate control. That may only be feasible if we enclose the orchards. Jaff has thought about installing misters elevated in the tree canopies as this would both humidify and cool the air around the leaves, ‘cloaking’ the harsh weather conditions beyond the orchard.

Whatever the solution, Jaff is eager to find it as this unnecessary nut loss is a major concern in this operation. Interestingly, this year the issue was greater in the Beaumonts (usually our hardy, more resistant cultivar) than the Nelmak 2 and A4 orchards.

A gorgeous bunch of Beaumonts.

Overall the farm has a favourable aspect. Most of it is either low lying or north facing. Winds from the south are responsible for the most of the leaf burn; even a cool wind from this direction can burn the leaves if it is pumping.

IRRIGATION

Jaff reports that the good quality water, which has a low EC, is key to their healthy orchards. EC is something that not a lot of farmers measure and, in Jaff’s opinion, they should as the impact on plant health is substantial. EC stands for Electrical Conductivity. It is a measurement of the dissolved material in an aqueous solution, which relates to the ability of the material to conduct electrical current. EC is measured in units called siemens per unit area (e.g. mS/cm, or milliseimens per centimeter), and the higher the dissolved material in a water or soil sample, the higher the EC will be in that material. In simple language; high EC means there’s a lot of ‘stuff’ in your water and more ‘stuff’ = more problems, like the kind high salinity or disease would bring. Low EC water is better because it is cleaner.

All Jaff’s macs are under microjet irrigation. Why did he choose micros instead of drip?

- They have sufficient water rights so volumes are not an issue.

- These are shallow soils and to get the moisture spread laterally, across this soil profile, would have required a lot of pipes in the drip irrigation system (which comes at massive expense). Micros can disperse water, across a broader area, far better thereby wetting the entire root zone.

- The sandier the soil, the more water will gravitate through it rather than spread across it. As these soils are very sandy, Jaff needed to distribute the water across the surface laterally so that it did not miss the roots.

- Soil health is a priority so Jaff wanted to wet the whole ridge so that soil health across the ridge was enhanced.

- Jaff knows that some of these soils drain poorly and need to be dried out cyclically. The micros grant hm the flexibility to wet thoroughly and then dry thoroughly and thereby be able to manage the soil health more acutely.

- Jaff’s focus on soil health means that he uses substantial amounts of mulch. Checking whether a dripper is working means that you have to dig through all the mulch to assess moisture of the soil below. Micros, because of their visual nature, mean that checking up on the system (making sure all trees are getting water) is much easier.

- Jaff likes being able to get water down quickly if the need arises and this is possible with micros. Under normal circumstances, he is averaging on 2 to 4-hour cycles at 63 litres per hour, every 3 to 4 days, on the younger trees, depending on the weather. As the trees grow, the supply increases. The aim is that the supplementary irrigation wets the top 200mm and rainfall attends to the deeper roots.

When it comes to investing in a new irrigation system, Jaff suggests that you employ a decent designer who can quantify costs of getting each litre of water to the fields in his proposed design. Warning: some guys will short-cut the laborious task of regulating pressure through using the right pipe sizes by specifying pressure-compensated nozzles. While these will regulate pressure, they are expensive and your system might not be structurally balanced with the sub-mains or lateral pipes, leaving you compromised because the nozzles are the only point of pressure regulation. Some labourers then find the nozzle works better without the compensator ‘flange’, so they remove it and this upsets the balance. Added to these challenges, pressure-compensated nozzles are much more expensive than regular micro jets when it comes time to replace.

Initially, when the trees were small, Jaff placed the micros 0,5m from the tree, with the stake between the nozzle and the tree, thereby making sure that the stems do not get a direct jet. Later, the micros are moved back to equidistant between trees. If you follow this, remember to allow for this movement when you put the irrigation system in by adding a loop in the pipe at the top of each row.

NURSERY

This is a commercial, SAMAC and SGASA registered nursery that has been producing macs for 6 years. About 3 years ago, they started working with Westfalia on avocados that have both clonal root stock and clonal budwood. This venture will go commercial this year and hopefully help to reduce the 7-year waiting period that is currently the case for farmers wanting these trees. I am going to walk you through the process as it is both interesting and Jaff plans to research clonal rootstock production for macadamias.

- Shortly after having come out of the dark – chlorophyll is slowly regenerating. 2. The root trainer within which the Dusa clonal root stock has developed its own roots. 3. Prepping for the budwood graft (Hass) on to the clonal root stock. 4. The triple decker – seed:clonal root stock:clonal budwood. 5. The clonal roots, now independent of the seedling.

Specially-selected, disease-free avo seeds are germinated. A clonal root stock (budwood from a Dusa tree in this case) is grafted on to this original seed stem. Once the graft material shows growth, the whole plant is place in the dark for 6 weeks. This is because chlorophyll is an inhibitor of root production in avos and we want the clonal root stock, grafted onto the seedling, to grow its own roots. When this plant comes out of the dark, it is completely white (void of all chlorophyll). A little container of growing medium (called a root trainer) is placed around the graft on the white etiolated shoots. Soon the plant grows roots in the trainer and builds up chlorophyll again. Root development can be checked by opening the root trainer (see picture 5 above). When growth is confirmed, the budwood (in this case, from a Hass tree) is grafted on to the clonal root stock. We now have a triple-decker avo tree. 🤣

Once everything is healthy and growing well, the original seed is cut off and the young tree with its own clonal rootstock is ready to bag.

One of the motivations for super root stock in avos is strong because of how prone they are to root fungi. Whilst macs are not as sensitive, the allure lies in better performing trees: think about an orchard that you’ve established with trees from the same batch ie: they most probably all have the same (ie: clonal) budwood and yet their health and yields differ vastly. The genetic difference is in the seedling root stock. When we identify a tree that is outperforming its peers, we can be fairly sure that the root stock is predominantly responsible. We can then use the very best budwood on the very best root stock to produce super macs!

Once Jaff has perfected the avo clones, he will turn his expertise to develop clonal root stock for macs but, for now, he uses Beaumont seedlings and the very best budwood he can find. He is ruthless in weeding out any tree that looks less than perfect and therefore has a high rejection rate.

Otherwise, the process is similar to most other nurseries: a sterile compost seed bed is used to germinate the best nuts. When ready, the tap root is removed and the seedling is placed in a 6-litre bag with well-drained medium (composted pine bark and coarse river sand). Multicote 8 and other micronutrients supplement this growing medium. Grafting is the key skill in this process and Jaff equips his specialists with the best tools. They also use two types of tape – one is very strong and binds the two pieces of material tightly (this is removed when the trees go out to hardening off) whilst the other is used to waterproof the top of the budwood. The tree is then tagged with full details on who did the graft, and when, so that they can identify any training requirements through failure rates. Once they’re sure the graft was successful, a second dose of Multicote 8 fertiliser is applied. Lately, I have learnt the significant difference between slow-release and controlled-release fertilisers; for anyone else interested to learn how this key factor affects your crop, watch this: https://youtu.be/Tg7iCy95Qb4

This nursery has already sold the 260 000 trees that will be ready by the end of 2021.

ESTABLISHMENT

As mentioned, this is Jaff’s real area of expertise as he has already had 138 hectares of experience over 4 years and is still going … with plans afoot for another 150+ hectares further south.

He chose to plant Beaumont and A4 first as they are the most precocious varieties and would bolster cashflow sooner. He planted equal numbers of both these trees, in alternating rows of 4.

Here you can clearly see the alternating cultivars; 4 rows of Beaumont (taller and darker) and 4 rows of A4.

He subsequently added Nelmak 2 and then 816, 842, 849, 863 and A16. 863 is unusual but some guys on the South Coast were raving about it so he decided to try it. I also heard from one of the fathers of the mac industry, Stephan Hoffman in Levubu, that this was his favourite variety because of the superior taste.

Earthworks

After clearing all the cane, the soil was treated with calcitic or dolomitic lime – about 4,5t/h, depending on soil analysis recommendations. It was then ripped and disced with the ridger to incorporate this well.

On much of the farm, soil depth was insufficient and tended to drain erratically so Jaff decided to ridge all orchards. They’re not high, averaging about 50 to 60cm and are an inverted V shape.

As you can see, the ridges are just high enough to facilitate good drainage and create a decent bed if the soil was a bit shallow. These are 2,5-year-old 816s.

When building ridges, you can either go for the upside-down V, as Jaff has, or a more platform shape with a flat top. As Jaff was sure he did not want any traffic on the root zone, he created V shaped ridges using 8 or 9 passes of a 22-disc contour maker. Jaff adds, “Offset mowers work better on V-shaped ridges as they don’t some in contact with the soil as they would on the corners of table top ridges”.

Planting

Jaff says the secret to this is to do it so that the tree doesn’t even know it’s been moved. Here’s a video detailing the process:

After planting, the soil around the base of the tree is covered with mulch and it is irrigated immediately with the system that was installed before the trees were planted. Initially Jaff was including pine bark in the hole when planting, especially with the heavier soils, but he’s no longer doing that as he didn’t see a significant return on the effort and expense.

Getting the roots to grow as soon as possible is key. They do this in the upper layer of soil so it is very important that this zone is kept cool otherwise they won’t grow there. Mulch will help to lower the soil temperature so be generous when putting this around the new trees. Amongst other stuff, Jaff uses interrow vegetation which is dispersed by the side-mower.

Another tip is to always have one person responsible for the planting the tree rather than two. A marker is placed at the end of each row indicating who planted that row and on what date. This facilitates informed decisions when assessing an orchard’s progress and staff training requirements. Also make sure that holes are dug before the trees go into the field and that they are placed in the shady side of the hole. The person doing the planting needs to do so within half an hour of that tree being brought into the field. A young tree left lying on its side in the field in full sun will get its roots burnt while in the bag.

All trees are staked using a 2.4m sharpened CCA H5 post. Place the stake just outside the ‘bag’ area, hammer the stake 60cm into the soil and brace at multiple points up height of the tree – this seems to have been key. Jaff says that 3m stakes would probably be even better as he only removes them about 2 ½ years later and that extra length would mean you could use it again – just cut off the lower part that may have rotted whilst in contact with the soil.

Finally, he advises that, due to genetic flaws, farmers should accept a loss of about 1% of the trees in planting. This loss may not be immediate and could be as much as 2 years later.

Trees are staked at multiple points against a very tall, sturdy stake which stays with the tree for 2,5 years.

Wind breaks

In the beginning, Jaff planted napier fodder in every second line, 2m from the trees. By the 2nd year it was competing with the young macs for water and nutrients. The considerable negative effects on the trees were clearly evident when compared to the rows without napier fodder. His recommendation is that, if you plant this grass, keep it at least 3m from the trees. Going forward, Jaff will plant seedcane rather than napier fodder as there is a return on it, it won’t compete as much with the trees and it is easier to remove.

As far as planting casuarinas to slow down the wind, Jaff has heard too many negatives to consider this option. ‘Tumbling’ is one that was new to me so I thought I would share it:

Wind breaks need to be configured very specifically to escape the ‘tumble’ effect that has the potential to cause severe damage. The success or failure of a wind break is a function of its width, density, height and distance from the orchard.

Because windbreaks require specific design, ongoing management and take up precious space and resources, Jaff believes that planting an additional row of macs as a sacrificial wind barrier is wiser. We also need to remember that the purpose of wind barriers in this crop is to maximise growth in young trees so anything planted needs to be quick growing to be of any use.

Spacing

Most of Jaff’s orchards have 416 trees per hectare, with an 8m x 3m spacing. He believes that it is important to get to tree canopy as quickly as possible and that macs love mulch and cool roots more than anything else. On new plantings he is spacing at 7m x 3,5m, with the understanding that he will have a lot of pruning material to mulch with later on. If you can start pruning at a young age and maintain the trees on an ongoing basis, it doesn’t matter if they’re close.

Justification for this tight planting was easy; the first trees were planted in 2017. The 2020 harvest of these trees, when they were exactly 3 years old, was an average of 5,9kgs per tree (nut in husk). Once dehusked and dried that came down to just over 2kgs per tree (DIS at 1,5%) which is 836kgs per hectare. The total harvest was 20 tonnes. If they had kept to conventional spacing, the 2020 harvest would have been closer to 15 tonnes. So, the additional trees have more than paid for themselves already.

Management capabilities are inextricably linked to orchard density. Jaff knows he is well-capable of maintaining and will purposely be keeping his trees small for a number of reasons (see Pruning).

Two-year-old Beaumonts (except for the closest tree which is 3 years old – it was kept in the nursery for one additional year in a 70L bag – although it is the same size as the 2-year olds, it has a lot more nuts)

Nutrition

Jaff keeps this simple by focusing on the objective. In this stage of his farm, that is growth. Before planting he made sure the calcium content and alkalinity level of the soil were correct. He ordered a granular blend that would address the soil deficits identified in the analyses as well as add a whole bunch of micro elements – this ended up as a 19:2:11 “which was close enough to the 9:1:5 I ordered”, smiled Jaff. He has applied this every 2 months, across the board, for the first 3 years since planting. The nitrogen is LAN-based, the potassium is sulphate-based.

Initially, each tree got only 50g, spread over a square metre around the base. For anyone wanting to start fertilising early Jaff adds; “Do NOT pour all that 50g into the area where the plant bag was, it will shock and potentially kill the tree, spread it out.”

In retrospect, he would have omitted the phosphorous completely as the soil really didn’t need it and he could have saved some money. This year, they started using CMS as the potassium supplement but he’s heard that CMS is no longer available.

Recent tests show that there is now too much nitrogen in the trees so he will cut back on this until balance is restored.

“More important than any fertiliser is mulch and shade so that the roots are kept cool and moist”, advises Jaff, “tweaking nutrients to stimulate yield is a guessing game – the highest performing A4s on the farm are in the same field as the lowest performing Beaumonts.” It is a big field – 6 hectares, with high carbon content.

A pile of smuts from the local sugar mill.

In the early days, when Jaff was eager to do everything by the book, he used foliar sprays but, as the returns are difficult to see, he has not applied them recently apart from a kelp product that has had good results on a farm in Eston where it was used to support stressed trees.

In his pursuit of early, vigorous growth on his trees, Jaff says that the best results are seen where the wind is least, thanks to the aspect being north facing and in a depression.

Check out the size of these Nelmak 2s!! And the one on the left (still very immature) is a twin. Apparently this is common in N2.

Pruning

Nothing ‘same-old-same-old’ here … I was delighted to encounter a few new concepts from Jaff:

- Create complexity from young. Simply put, this involves training the tree to be ‘full’ from the beginning. They do this by removing the apical meristem of any branch over 50cm long. This forces side shoots and from those, new branches will be selected. They now start this training in the nursery when the tree is at about 60cm high. The result is nice, strong, low branches.

From these shoots, Jaff selects the strongest.

- Once the tree is tall and full, it is time to thin out. Jaff selects the strongest, most fruitful branches and remove others so that sunlight penetration is optimised.

- Jaff keeps the trees under 4,5m high. He was inspired by a Nelspruit farmer who planted 6m x 4m, and kept his trees under 4,5m high. These Beaumont orchards are consistently delivering over 6 tonnes per hectare (DIS).

4. Jaff encourages a central leader with as many side branches as possible. A tree with a single leader is far stronger than one with multiple leaders. is strengthens the tree against wind damage.

5. It is important that crotch angles of side branches are big; he has learnt that narrow crotch angles are weak points.

This Beaumont tree is at risk of splitting because of the multiple leaders. It has also gotten too dense and needs to be thinned out.

PESTS

Straight up Jaff announces; “I can’t teach anybody anything about pests.” Not only is it a little early for him to have any significant pest issues, he has also handed the portfolio of pest management to his brother. Jaff says their thrips issue is inherent from the cane and he is using the same range of chemicals as they did on the cane.

Ants and aphids together are sometimes an issue and they spray locally for those infestations.

They found their first stink bug this year, near a bush line. Although the pressure is low, they do have a spray programme lined up for this season and have started to spray.

There are moth traps scattered across the farm so that tabs can be kept on this class of critter. So far, so good.

Whenever they are forced to spray, the farm policy is to prioritise efficacy and the use of ecologically-friendly options over cheap alternatives. They will also be focused on preserving pollinators by spraying at night, especially in flower season.

Just a reminder to any other farmers new to macs, there is a whole article on the common pests: https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2020-7-pest-management/

DISEASES

Again, it’s a little early in the game to have too much disease pressure. The ridged fields discourage Phytophthora but Jaff believes it is something you’ll always have to deal with because some trees are just genetically susceptible to it. They were putting fertiliser bags around the stems of affected trees to prevent irrigation water hitting them but have since learnt that this compounds the problem because the trees don’t get enough air circulation and they stay damp for too long after rainy conditions. He groans, “and the learning process continues!”

Jaff medicates the sick ones for a while and then makes a call as to whether it would be better to replace.

They had to spray for blossom blight this year and there was a small amount of rats tail in A4s. Overall, Jaff is prepared, but unconcerned, about the pest and disease challenges ahead.

This stem protection on a recovering phytophthora patient has proven ineffective; as much as it keeps the irrigation water off the stem, it also inhibits airflow after rainy weather.

PEOPLE

There were 3 gems I extracted as far as personnel resources are concerned:

- Get decent quality team leaders. There are lots of agriculture varsity students struggling to find fulltime work – employ them; they are interested, inclined to the agricultural sector and incredibly knowledgeable.

- Communicate with staff. If they understand WHAT they are doing, WHY they are doing it and HOW it works ie: desired outcomes, they will do a far better job. Take spraying as an example; it’s an ongoing task so investing the time to explain to the team what, how and why only needs to be done once for each chemical. By taking it a step further and keeping them informed of successes or failures, you will achieve more.

- Keep it clean. Rather than allow an opportunity for an infected knapsack, keep two separate sets – one for weedicides and one for foliar sprays.

RESULTS

Only the Beaumonts, A4s and Nelmak 2s are in production. The ‘8s’ have a handful of nuts but not enough to be considered productive. The Nelmak 2s are an impressive size and taste great. 814s are small, compared even to Beaumonts.

Results need to be assessed in terms of both QUALITY and QUANTITY.

As Jaff’s trees start producing and he is contemplating which varieties are best. He does this by assessing both the QUANTITY each cultivar delivers (yield per hectare) and the QUALITY (style spread, TKR and market value/trends). By pulling all these factors on quality into one spread sheet, we can establish value, per kg of nut in shell, across the different cultivars. This amount, with the yield per hectare, gives a far more accurate account of what the best cultivars are.

A fictitious (but proportionally accurate) price was used in this illustration. The style spread and TKR are accurate as supplied by a prominent processor for a major region. The objective of this illustration is to highlight the importance of knowing the QUALITY you get from each cultivar as much as you know the yield. This info helps in knowing which cultivars work best for you. To complete the assessment, you need to apply your PRICE OF NUT IN SHELL to what each cultivar produced on your farm – this will show you the overall result per cultivar.

Using this type of assessment, Jaff’s Nelmak 2 and A4 have out-performed Beaumont at this point. Jaff has been advised that Beaumonts will catch up later which is so contrary to what has been the message thus far, in that Beaumont cultivar is the precocious, early cashflow injection, essential to every business.

Obviously, the accuracy of this information is affected by the detail of your records, how refined your deliveries to the processor are and whether the processor can give detailed results per batch. But, if you are not able to work to this level of detail, your processor will have performance figures for each cultivar as an average in your region. These can be used in a table like the one above to give you an indication of cultivar QUALITY in your region.

And this discussion raised the topic of how to really improve your outcomes …

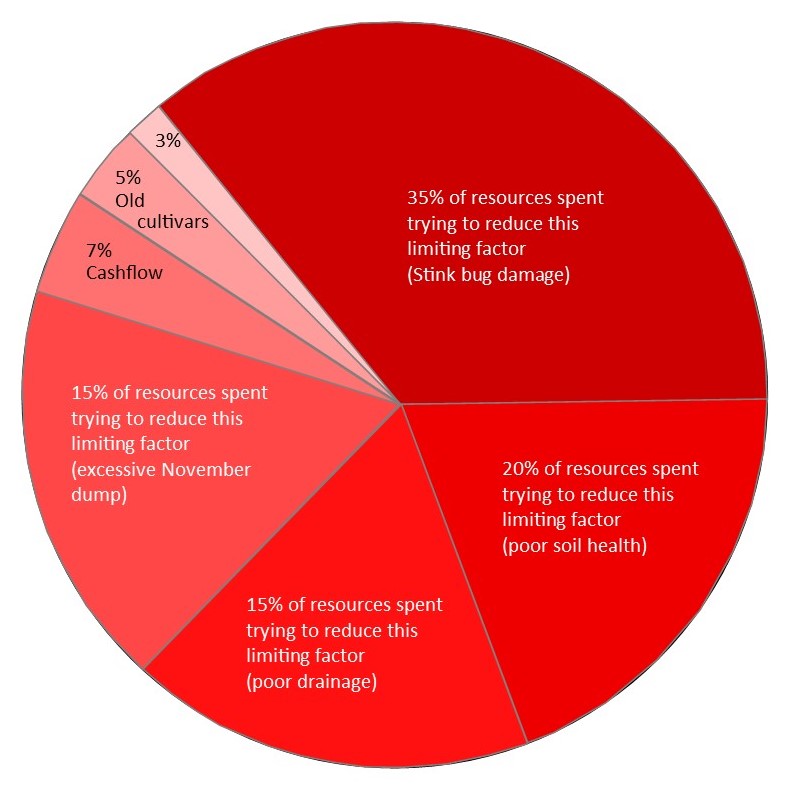

LIMITING FACTORS

Jaff sparked such an interesting discussion when he questioned whether we keep in mind the extent of the limiting factor when we decide how to deal with it. A limiting factor is anything that limits (or takes away from) your result. So, if you start off with 1 million flowers but you end up with 200 000 nuts, you’ve lost 800 000 ‘possible nuts’ – the factors that lead to that loss are your limiting factors.

There is obviously a maximum carrying capacity for each tree (which is a lot less than the flowers it produces) It is important to establish what factors might be limiting you from getting that full load to market.

Examples of limiting factors are weather (drought, floods, heat waves etc), soil (quality, content, drainage), water (supply, quality, movement, irrigation issues), cultivars (poor performers), pests, sunlight (poor pruning), management, staff etc etc. In order to make sound management decisions and know where to spend time and money, we need to first assess the impact of each limiting factor. To illustrate this in context, Jaff and I began this discussion when I asked him about cross-pollination. He countered with this question: “if we are losing so many pollinated nuts due to external stress factors causing trees to adjust their crop load, why try pollinate more nuts? Maybe I should be focusing on reducing the plants response to these stress factors, or enabling it to carry a greater load?”

There are two elements that come up there; 1. How big a limiting factor is cross-pollination, or even pollination? The next TropicalBytes article will address this topic 2. How do you decide what gets your priority focus?

Every enterprise has its own set of challenges (limiting factors) at varying degrees (weightings). The big question is: are we assigning the relevant time, money and attention to the factors we are dealing with? The suggestion is simple:

- List your possible limiting factors – example below.

- Rate them from highest (the ones that take the most away from your 100%) to lowest (those that do not take much away from your results).

- Weight them – allocate a percentage to each. This percentage represents how much of your 100% this factor is responsible for stealing.

- Allocate your efforts accordingly.

Here is an example of what this might look like for your farm:

| Limiting Factors | Rating – highest (1) to lowest (7) cost to the business | Weighting – how much are they costing? (If the total of all your limiting factors was 100%) |

| Poor soil health | 2 | 20 |

| Poor drainage | 3 | 15 |

| Stink bug damage | 1 | 35 |

| Excessive November dump | 4 | 15 |

| Cash flow | 5 | 7 |

| Old cultivars | 6 | 5 |

| Pollination | 7 | 3 |

Learnings from the rating and weighting example above:

35% of our time should be spent on reducing stink bug damage. Whether that is investigating better spray programmes, better pruning, scouting might be an issue etc etc.

20% of our time should be spent investigating how to improve soil health – that might include better composting or implementing a mulching plan or investigating what microbial supplements would do …

… and so on. The aim is to make sure that management is focusing on the things that will make the greatest difference to the bottom line and ensure a profitable and sustainable business (or whatever our unique goal is).

An example of how quantifying limiting factors can be used as a resource management tool.

This exercise will need to be repeated regularly as we solve some issues and a refocus of resources is required.

MULCHING

What does Jaff believe is his greatest limiting factor? Soil health was the answer, and Jaff is addressing that through mulch. He gets this “from everywhere and anywhere”. Being close to the sugar mill, he uses a lot of the smuts which have a nice high carbon content and promote the diversified soil life he is looking for.

He has used compost conservatively, avoiding anything animal-related for fear of introducing something harmful in the undefined contents. He does believe that manure that is well understood (in terms of its contents) can be hugely beneficial to microbial life in the soil.

Whatever he places around the base of the trees as mulch will eventually turn into compost so he is satisfied that, by continuously mulching, he is effectively composting as well.

An offset disc mower works really well in cutting the interrow vegetation back and it can be pulled by a 40kw tractor. It keeps traffic off the ridges.

THE FUTURE

Sometimes the great mac prices seem too good to be true, and it’s hard not to anticipate a decline so I asked Jaff how he felt about this, considering his substantial investment over the last 4 years. Jaff is unconcerned and believes that macs will erode into other nut industry’s market shares before they decline themselves. But I really enjoyed his perspective on the unlikely event that mac prices do decline to the point of driving some farmers out: he said, “Don’t be that farmer. If the market becomes flooded and some are lost, make sure it’s not you. The best farmers will survive so be the best!”

And with that, I was happy that we had indeed been blessed with time with one of the country’s very best mac farmers. It’s too soon to have the results to prove that but … watch this space!

The new processing facility still under construction.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

https://www.worldweatheronline.com/gingindlovu-weather-averages/kwazulu-natal/za.aspx

https://bmcbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12915-016-0230-0

http://apps.worldagroforestry.org/Units/Library/Books/Book%2006/html/8.9_trees_as_wind.htm?n=90