It was so exciting to get out and see the world again; with Lockdown regulations relaxed enough to make it legal I wasted no time in racing down to the South Coast of KZN to meet a farmer who had been recommended as someone we could all learn from.

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 30 June 2020 |

| Area | Scottburgh, KZN South Coast |

| Soils | Parent soil is mostly Granite. There is a lot of Coastal Sands and Table Mountain Sandstone (TMS) Not a lot of clay or loam. |

| Rainfall | Ave annual rainfall of 1200 mm |

| Altitude | Approx 20m above sea level |

| Distance from the coast | 2 to 3 kms as the crow flies |

| Temperature range | 12 to 27 °C |

| Varieties | 12 years old: 788 – 6 ha, 816 – 11 ha

New orchards: A4 – 8.3 ha, A16 – 5 ha, Beaumont – 9.7ha, 814 – 5ha |

| Hectares under mac | Total: 45 hectares currently |

| Yield | 4,2 t/h WIS |

| Quality | 40.12 % Total kernel recovery (sound kernel) |

| Other crops | 318 hectares sugar cane

80 hectares timber – Gum (Grandis) |

It seems that the KZN South Coast is considered, by most mac farmers, to have the perfect climate, in South Africa, for this crop. The high humidity and mild temperatures, with no great extremes, make up for the seasonally strong winds. This graphic below shows the weather averages for Scottburgh, KZN South Coast:

Wind speed is highest in October with the mean average, at this time, being 20kph although it does sometimes get up to 35kph. The calmest time of the year is in May, when the average wind speed is 15,5kph.

FARMER CONTEXT:

Jaff has been on this particular farm since 2007 when he was employed as a farm manager. He grew up on a farm in Melmoth, is a career farmer, who studied agriculture via correspondence and has experience with a number of crops, including citrus, but is loving the current mix of sugar cane, macs and a little timber on this expansive farm.

The proximity to the coast means that eldana in the cane keeps Jaff on his toes but he seems to have found a spray recipe (piggy-back strategy) that allows him to retain sanity and keep a positive outlook for the future of the sugar industry. Unlike macs, sugar cane has not thrived on the South Coast like it has in other parts of the country, but considering that it almost all dry-land, the results manage to keep farmers in the game. Macs have been a much-needed diversification though, especially since cane prices dropped.

When Jaff arrived here, there was plenty of work to do – but he quickly established that soil acidity was probably behind most of the issues. Correcting that is a process – one that he focuses on every year. Ripening has also made a difference to cane quality, which is a valuable compensation for the low tonnage.

Jaff has chosen to use sandier soils for mac expansion as they certainly prefer this to heavy clay. The upside is that the cane in this soil is maxing out at about 64-65t/ha so it is not a difficult decision to replace some of this marginal cane with mac orchards.

AN EARLY START

14 years ago there were not a lot of farmers diversifying into macs but, after an extensive investigation into diversification options, this farm dipped their toes in the water with 12 hectares. They then took a break to assess the outcomes of this brave investment and there is an 11 year age gap between the original orchards the next youngest. Jaff explains that this is a fertile area and therefore a broad range of crops that were viable and had to properly evaluated. Ultimately, the positive results this farm has enjoyed from macs meant they decided to continue, limiting the diversification to new cultivars, irrigation methods and fertiliser applications.

Initially they planted 788 and 816, alternating a row of each throughout the orchard. They were youngsters when Jaff arrived and he has enjoyed watching them come in to production in 2011/12. “The first harvests were delivered in fertiliser bags,” laughs Jaff as he thinks about how far the industry has come in such a short time.

I have heard farmers comment about challenges when varieties are interplanted in the same orchard but Jaff says he hasn’t experienced any trouble; but I do pick up that he has also learnt HOW to farm with this layout and although he is fairly unphased by the adaptations he has had to make, a farmer used to single cultivar orchards may be more aware of the differences.

The 788s were flowering profusely when I was there, with just a smattering of blossoms on the 816s. Even though 788 is considered an early flowerer, I was shocked to see such profuse early flowering, as this was only late June! Jaff explained that they had some coastal rains (50mm at the end of April and 44mm in June) and he suspected that has been behind this show.

Jaff’s 788s were flowering profusely, remarkable considering it was only June.

Jaff’s 788s were flowering profusely, remarkable considering it was only June.

HARVESTING

Early on Jaff made a decision not to use ethapon. He taught the staff how to decern an immature nut from a mature one by the colour of the husk. In his first season; 2012, they picked the nuts from the trees and ended up delivering an unacceptably high number of immatures. He realised his lessons on what to pick and what not to pick had not landed. Since then, his pickers only gather what has fallen. He still does not use any ethapon so the season is very long, starting mid-Feb and ending mid-July. The trees are always carrying nuts across all stages of development, which I witnessed when I was there. With only the mature nuts falling, the farm enjoys a less frenetic, extended season with a zero immature delivery rate.

Harvesting on this farm is the only ‘untasked’ activity. Jaff makes sure there are always managers in the orchards and he trusts the staff to do the best job. With no ethapon and no picking out of the trees, it is hardly fair to task the pickers as they are limited by what has fallen. Jaff keeps an eye on productivity and balances that with the costs – he’s happy that it is a win-win arrangement for the whole team.

Now this is a happy picture! Besides showing that there are mature nuts and various stages of flowers on the tree at the same time, we also see a healthy bee and evidence of a spider.

Now this is a happy picture! Besides showing that there are mature nuts and various stages of flowers on the tree at the same time, we also see a healthy bee and evidence of a spider.

Jaff is still expecting another flush of flowers in September, by which time these flowers will be pea-sized nuts.

Only at the very end of the season, which is now, will they go through the orchards and pick any really late nuts off the trees – at this stage a mature nut is very distinctive. They are also busy pruning the 816s currently and this delivers a decent harvest from the cut branches. After this, their harvest season will finally be closed.

So, once the nuts are in the farm’s processing hoppers, they are dehusked. At the beginning of the season, he will put a water bath in ahead of the front of the sorting tables to catch any old nuts that may find their way in. When they are sure the old nuts are done, they’ll remove the bath.

The nuts are then sized to remove any smalls and then it is on to the sorting table and in to the drying bins. Jaff is only using ambient air. Working for directors means that all investment decisions need to be financially justified – which should happen on all farms! Jaff investigated the options thoroughly – a drier would cost about R200K. The drying costs, deducted by the processor only amount to about R12000/year. Conclusion: at current volumes, the drier cannot be justified. And driers bring a whole new set of challenges and additional costs so Jaff is relieved to not have to face any of those just yet.

Before the nuts are put into the one tonne delivery bags, they are sorted again and then the processor collects the full bags.

While on the topic of productivity, I always find it interesting how cooked meals impact it. I know that I would be WAY more productive if I didn’t have to worry about planning, shopping and cooking. Jaff has found this to be the case with his staff and has a full-time, dedicated cook who prepares two cooked meals every day for the staff living on the farm. He’s done the maths and is quite sure the investment is wise.

A little late-season load

A little late-season load

CULTIVARS

In the new orchards, he has planted A4 and A16 as they are considered mid-season cultivars. He has also added the mandatory Beaumonts and 5 hectares of 814, bringing the current mac operation to 45 hectares. I pressed for a favourite but Jaff says it’s too early to compare the youngsters to the productive trees. He says the 788s are perfect for this farm – he knows that some farmers struggle with them but he is more than happy with their performance. He enjoys their growth habits, which are more open and let the sunlight in with less manipulation required.

These are 816s that were transplanted out at 6 years; they did very well with almost a 100% take.

These are 816s that were transplanted out at 6 years; they did very well with almost a 100% take.

Jaff is concerned about the characteristically small kernels and thick shells of the Beaumonts but he did a calculation of what the Beaumonts would need to bring to the table to keep up with what the rest of his team is doing: this farm produces very high whole kernel percentages (about 70%). As Beaumonts are known to produce more halves and pieces, he wanted to see how much volume he would need to realise the same return per hectare. The result was 5,3t/ha (based on industry averages) compared to the 4,2t/ha he is getting now, with 70% wholes. After talking to advisors and neighbours, he is confident that they will easily achieve that target with the Beaumonts. Jaff emphasised that doing this kind of calculation is important when making decisions on what to plant and what to expect from that field / cultivar – how else do you know if you’re on track or not?

The next expansion includes 1170 x 842, 780 x 814 & a further 1170 x A16. The land was being prepped while I was there …

Land prepped and ready for the new 842s to go in this spring.

Land prepped and ready for the new 842s to go in this spring.

ESTABLISHMENT

While I was visiting, the farm was hard at work getting ready for new plantings. Jaff explained that they use the ridging technique in prepping the land. As they are so close to the coast, the water table tends to be very high, and to avoid any root trouble – phytophthera etc – he uses ridges to elevate the trees as much as possible.

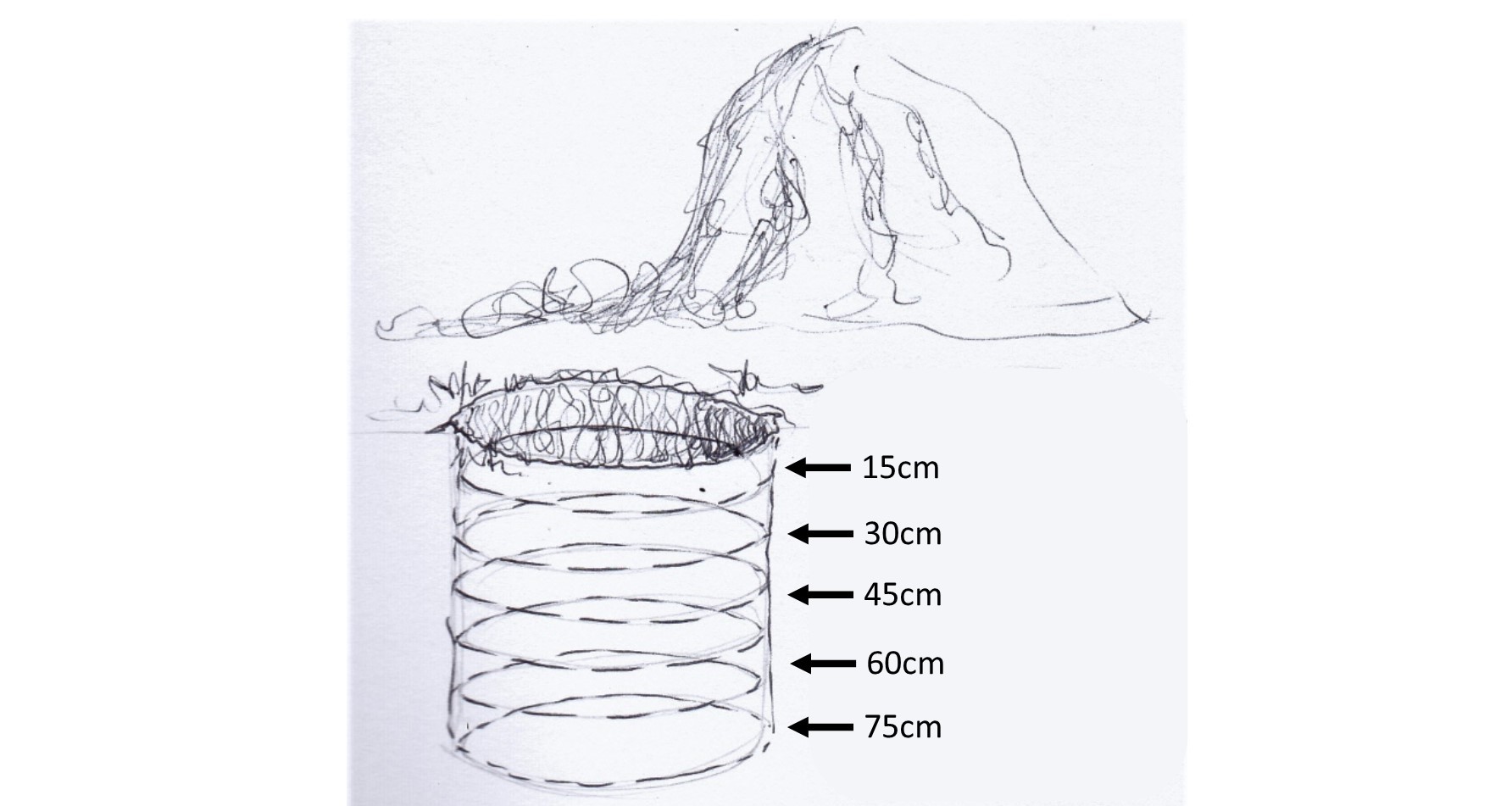

Way before that starts, there is a long road of preparation which starts with soil testing. Jaff digs about six 1 metre deep pits per hectare. He then takes a soil sample every 15cm and gets an analysis done on each level throughout the orchard i.e.: a result for 15cm, across the orchard, a result for 30cm, across the orchard, etc …

Through these analyses, he has learnt that phosphorous and potassium do not move through the soil profile, even after considerable rainfall. He usually sees that 80% of the phosphorous and 48% of the potassium will remain in the top 10cm. So Jaff concentrates on getting these two elements lower down in the soil profile during land prep. This is his one chance to get those minerals into the lower profiles for the next 60+ years! Once the requirements for the full orchard depth have been calculated, he broadcasts the fertiliser and works it in with a disc or harrow. They will then deep-rip in preparation for the bulldozer which will come through and turn the ridges. The ridges are built up to between 600 and 800cm, effectively leaving a soft bed of about 1,2 to 1,6m in depth that has all supplements spread through it evenly.

Jaff has found that, when it comes to pushing ridges, bulldozers work so much better than anything else, inc graders.

Jaff has found that, when it comes to pushing ridges, bulldozers work so much better than anything else, inc graders.

Newly cut ridges, almost ready for the trees.

Newly cut ridges, almost ready for the trees.

Jaff uses a standard spacing of 8m x 4m. Keeping all orchards uniform, he minimises spray issues. But then he confesses that he does have one small (2,5ha) orchard of A4s that he has planted at 7m x 4m. For this fertile valley-bottom experiment, he has set a personal goal of 5 t/ha with a 50% Total kernel recovery (sound kernel). This orchard is currently 18 months old.

I was flabbergasted to see nuts on this 18-month-old A4! Jaff just smiled proudly. All that they have had, in terms of supplementation is 150 gms of Multicote juvenile about 1 – 2 months after planting. From year one they got 60 gms of standard Kynoch fertiliser. From year 2 – 3 they will get 90 gms every 6 weeks.

I was flabbergasted to see nuts on this 18-month-old A4! Jaff just smiled proudly. All that they have had, in terms of supplementation is 150 gms of Multicote juvenile about 1 – 2 months after planting. From year one they got 60 gms of standard Kynoch fertiliser. From year 2 – 3 they will get 90 gms every 6 weeks.

Jaff has a 3-hectare test block that is under microjets. It is a personal trial wherein he is comparing micros with Kynoch blends to fertigation.

When planting into these soft, well-aerated ridges, no special preparation of the hole is necessary. Jaff just digs a hole slightly bigger than the bag. He then uses fertiliser-spiked hydrogel. This comes in a powder form and he mixes 1kg in to 20 litres of water to create a porridge-like gel. Each hole gets a 2 litre jugful and the small tree is placed on top of that before being tucked snuggly into its new home. Although these trees are drip irrigated, he prefers to cover his bases with this hydrogel as sometimes the dripper does not line up accurately with the young tree. Jaff does not apply any additional fertiliser or compost at this stage.

A marked difference between the original mac orchards and these new plantings is that the new ones are drip-fertigated and are planted in single-cultivar blocks – this allows Jaff to tailor their irrigation and nutrition requirements precisely. The new blocks are small enough and in close enough proximity to facilitate efficient cross-pollination.

As an alternative to the hydrogel, Jaff investigated using plugs that would take the water from the nearest irrigation pipe hole (plug) to the tree (if it didn’t line up) but that costs in the region of R3500 per hectare. When he considered the fact that the hydrogel also had fertiliser (NPK, no micronutrients), he decided on that route. Jaff hates loosing trees – even one hurts – the cost is one thing but the hassle of securing another tree, getting it to the field, digging, planting and caring for it out of sync with the others is more hassle than he has time for, so he works hard to make sure that every one of his young trees flourish.

Young trees HAVE to be of the very best quality. Jaff advises that you do not compromise here. When you’re looking around at nurseries / suppliers, price must not be a consideration.

Jaff emphasised that another factor in his planting success is to make sure that the trees are not left exposed for more than is necessary. He has a team that un-bags and another that plants. He says the distance between these two operations must be minimised to ensure that the tree has every opportunity to thrive.

Jaff stakes all the trees because of the high winds on the coast. In this environment, it is not only the young A4s that struggle. He uses bamboo and places the stake at a 60° angle that will withstand the wind in the direction it is strongest. It is important that this stake is not put into the root mass as the damage could be fatal. Strap the upper end of the stake to the tree with elastic.

Staking the new trees is standard throughout the farm and is done with some important principles

Staking the new trees is standard throughout the farm and is done with some important principles

About 12 weeks after planting, Jaff will start fertigating the new trees.

Wind breaks of casuarina trees are used extensively on this farm to help buffer the high winds. Jaff has noticed that the macs closest to the casuarinas have not done well and has purposely allowed a wider gap between the orchards to minimise any impact.

Left: New casuarina wind break planted far enough from the macs to minimise competition. Right: The wildlife here actually prefer the casuarinas to the mac trees and Jaff has been struggling to get them going.

Left: New casuarina wind break planted far enough from the macs to minimise competition. Right: The wildlife here actually prefer the casuarinas to the mac trees and Jaff has been struggling to get them going.

I asked about using artificial windbreaks like poles and shade-cloth but Jaff explained that these highly versatile building materials would very quickly “grow legs” …

Preparation of the waterways (left) which are planted with buffalo grass (right)

Preparation of the waterways (left) which are planted with buffalo grass (right)

Jaff knows the frustration of trying to getting the more out of macs that were not planted in land that was adequately prepared (the original orchards), and therefore emphasises the value of investing in this key phase of establishment. In an attempt to relieve the compaction and correct pH levels in some of the original orchards, he is currently deep ripping and adding dolomitic lime through the interrows.

PRUNING

About 2.5 ha of the Beaumont trees are rooted-cuttings. Jaff has found that they tend to ‘lollipop’. As a result, he has had to go through the orchards and prune them earlier than usual. Ordinarily, he does not prune young trees, preferring to only get the shears out around year 5 but he does do some manipulation that will start the trees off with a good shape.

Beaumont rooted cuttings

Beaumont rooted cuttings

Jaff does manual manipulation when required and uses whatever tools are close at hand – today, it was rocks. He says it is important that these measures are temporary and that all ties and ropes are removed long before they damage the branches. If you can’t get around the farm in time to remove the ropes, rather don’t employ this strategy to open trees.

Jaff does manual manipulation when required and uses whatever tools are close at hand – today, it was rocks. He says it is important that these measures are temporary and that all ties and ropes are removed long before they damage the branches. If you can’t get around the farm in time to remove the ropes, rather don’t employ this strategy to open trees.

Jaff likes to keep his trees relatively short at to 5 to 5,5m. He does not do any skirting and, when he sees all the nuts his trees produce on these lower branches, he cannot understand the practice at all. He estimates the volume off these lower branches to be around 1 to 2 kgs per tree. Doing the maths, that can make a difference of R35000/ha. Surely pickers could be encouraged to manage around these lower branches when that sort of money is on the line? Besides the money, the shade thrown by the leaves on these branches help to keep the soil cool and therefore better hydrated – another factor that certainly plays a part in supporting high producing trees.

Jaff finds that the Beaumonts need the most manipulation and training to open them up. Looking at the young A4s, he suspects that they may be the easiest as they are opening up nicely on their own but they are too young to be sure.

Jaff has the highest regard for his pruning team whom he believes do a brilliant job. They have lived with the 788s and 816s long enough to know them well. The 816s require much more attention as they tend to close up. 788s are a lot easier and generally only need a few windows opened at the end of each season.

Jaff recommends that all farmers teach their staff that whatever they do this year, affects the farm’s income in the following year.

Jaff says that this battery-operated chainsaw has literally changed their lives! Pruning is now a much quicker and safer activity. The pruning team is made up of three people – a chainsaw operator, a ‘hooker’ who pulls the cut branches out of the tree with a long pole that has a hook on the end of it and a tidier who places the branches in the middle of the row, ready for the mulcher to do its thing. These are 816s pictured.

Jaff says that this battery-operated chainsaw has literally changed their lives! Pruning is now a much quicker and safer activity. The pruning team is made up of three people – a chainsaw operator, a ‘hooker’ who pulls the cut branches out of the tree with a long pole that has a hook on the end of it and a tidier who places the branches in the middle of the row, ready for the mulcher to do its thing. These are 816s pictured.

Jaff explains that they will never cut more than 30% of a tree in a season. They aim to take out a substantial branch on either side, and one in the middle.

FERTILISER

Four to five months after planting, Jaff will come through and compost the trees with a homemade blend of cane tops, mac husks and chicken litter. He applies it quite thick so that it also helps to suppress weeds. If the orchard had cane planted in between the rows, all that trash goes under the macs (for those of you who are not cane farmers – sugar cane that is not burnt before harvest yields a lot of green waste in the harvesting process – this is called ‘trash’). Jaff has chosen to grow all their seed cane in the young mac orchards. This is a very successful use of the open (often wasted) space in between the mac rows and can be done for the first 3 to 4 years.

Seed cane growing in the new orchard interrows.

Seed cane growing in the new orchard interrows.

Jaff does regular soil sampling in the cane fields as well and will have 4 to 5 blends come on the farm, catering for the all the unique soil requirements. “The days of blanket fertilising are over,” smiles Jaff. “Every bag that comes onto this farm is KynoPlus – the one with the coating. Just look at how green my cane is!” He believes that this is down to the reduced nitrogen volatilisation (the coating reduces the expensive loss of this vital nutrient) and the micros in the KynoPlus product.

No photo editing, I promise! The cane in the foreground shows the vibrant green that Jaff is so excited about. The distant fields have been ripened with ethaphon and are close to harvest.

No photo editing, I promise! The cane in the foreground shows the vibrant green that Jaff is so excited about. The distant fields have been ripened with ethaphon and are close to harvest.

Jaff explains how they top dress with Prelude from Kynoch once a month – on the left, he points out the growth the trees have had in the last 6 months and lays a lot of the credit to the fertiliser choice. On the right, he counts 14 pea-sized nuts that he knows will all make it through the November dump.

Jaff explains how they top dress with Prelude from Kynoch once a month – on the left, he points out the growth the trees have had in the last 6 months and lays a lot of the credit to the fertiliser choice. On the right, he counts 14 pea-sized nuts that he knows will all make it through the November dump.

ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS

I am always curious about how successful farmers assess the plethora of offerings the market is currently pushing in the faces of mac farmers. Jaff seems unruffled and open to reviewing the claims of the products but he always investigates the active ingredients and claims of the products and what the implication of the application would be.

Currently he is using flower initiation sprays and nut set or boost sprays. He has also used a product that claimed to prevent early nut drop and it seemed to have worked, but he never seems to change only one thing in isolation, making it difficult to assess exactly what lead to the outcome.

As much as possible, he prefers to keep the trees well-fed and hydrated and lets nature do the rest. After all, healthy trees will also drop fewer nuts.

Jaff has noticed a distinct pattern of alternate bearing in the mature orchards and has been on a mission to get to the bottom of the phenomenon.

… he has started with supplementary feeds earlier in the season. By now (late June) he has already applied two foliar sprays with micro-nutrients like copper, zinc, calcium etc. and he believes this is behind the ‘flattening of his roller-coaster ride’. He emphasises that he is not using any MORE supplements, he is just coming in a lot earlier. He believes the result is that his trees are fortified to carry a heavier crop and there drop fewer nuts.

Jaff believes that one of the major differences between top farmers and average farmers is whether you are blindly following a spray programme supplied to you by the people who make money out of the volume of product you buy, or whether you are focused instead on what is best for your long term outcomes. He is resolute in spraying only what the orchards need, rather than what the “recommended programme” is. As a result, he sprays more often, with more precision and the results are evident …

Jaff’s storeroom was full of interesting things. He is clearly passionate about microbes and micro-nutrients. He explains that he tailors sprays, keeping accurate records and results. “Eventually you start to figure out what works,” he explained that this includes things like whether foliar is better than soil applications. He believes copper is best addressed through the soil when the deficiency is acute.

Left: magnesium deficiency. Right: the copper deficiency in this tree is shown in the curved branches.

Left: magnesium deficiency. Right: the copper deficiency in this tree is shown in the curved branches.

IRRIGATION

All cane here is dryland and the mature macs have micro-sprinklers so Jaff has enough water-management experience to slow down his decisions on what to do with the new mac orchards. For two years (winters), he monitored the flow of water into the dam and with that information, he sat with the irrigation company to design a sustainable solution. After a thorough assessment of all options, they decided that drip fertigation was going to produce the best returns. Key to this decision was that, with the water they have available, they would have to cap the expansion into macs at 40 hectares if they went the micro-sprinkler route. With drip, 80 hectares was realistic, even without having to consider boreholes and other (emergency) measures. Ultimately, having the option to expand further was what made the considerable investment in drip worthwhile.

Jaff is a can-do, highly resourceful and capable man. When he set about putting in a state-of-the-art fertigation system, he knew it did not have to cost both arms and legs (one of each was enough)!! Coupled with this McGiver-ingenuity is a wise caution – he has done plenty of homework and plans to do a whole lot more. He explains that, unlike cane, macs are not always a forgiving crop – you need to farm with attention and care. After these current fields are planted, he will once again take a break, reassess, consolidate and learn from the results before continuing the expansion.

Since putting in the new system and monitoring what the tree’s actual requirements are, Jaff realised how much he was over-irrigating before. He is certainly not alone in this. The picture above shows how easily too much water kills mac trees. The trench above these trees will hopefully save the replacements from the same fate.

Since putting in the new system and monitoring what the tree’s actual requirements are, Jaff realised how much he was over-irrigating before. He is certainly not alone in this. The picture above shows how easily too much water kills mac trees. The trench above these trees will hopefully save the replacements from the same fate.

Perhaps I have never paid attention before, but I do not recall ever seeing these ‘governing’ tags over the head of the sprinkler. Jaff explained that they are there for the first few years of the mac’s life and, when a bigger area needs to be irrigated, it is easily removed.

Perhaps I have never paid attention before, but I do not recall ever seeing these ‘governing’ tags over the head of the sprinkler. Jaff explained that they are there for the first few years of the mac’s life and, when a bigger area needs to be irrigated, it is easily removed.

FERTIGATION

The original orchards run off a stand-alone micro-sprinkler system, fed by their own reservoir. These trees get granular fertiliser. Jaff is a devout fan of Prelude fertiliser from Kynoch. His faith lies in the KynoPlus coating which permits slow release and preserves the nitrogen which would normally volatilise before water takes it into the soil where the tree can access it. He applies this five times every year. Recently he has found that the soil analyses are indicating high levels of phosphorous so Kynoch is mixing him a specially formulated blend that excludes P.

The new orchards are where the fertigation system has been installed. When the trees are small, a single line of drippers is used. When they start producing, a second line is put in and a third when they are big enough to warrant it.

There is a dripper at every 1m along the pipe, emitting 0.9 litres per hour. When the trees are young, the pipe is placed close to the stems and moved to 600mm away when the second line goes in. The third line will be placed outside of the first two, encouraging the roots to extend.

Each block is controlled individually, with soil probes giving guidance as to when irrigation should be turned on or off.

Here, three important features are illustrated; the probe transmitter, the interplanting of sugarcane in the young orchards and the new wind-breaks (casuarinas) running between the two orchards.

Here, three important features are illustrated; the probe transmitter, the interplanting of sugarcane in the young orchards and the new wind-breaks (casuarinas) running between the two orchards.

The new drip irrigation system is tri-filtered; at the dam, at the pump house and again in the field.

Jaff used all his technical skills to deliver this state-of-the-art system at a reasonable price. As you all know, mention ‘macadamia’ and the price usually trebles. He also found that there were a few bits and pieces he had to get creative with, like a tool to mix the fertiliser in, as the systems are not sold complete.

The cost of fertiliser in this system is more expensive but you don’t have the ongoing application cost (labour) so Jaff says it balances out.

As this is a pressure driven system, over-irrigation is a risk if there is a small leak somewhere. They have a dedicated irrigation specialist who checks on any discrepancies, e.g.: a field was supposed to get 5l but it got 6,5l. Then he will walk every row in that orchard looking for the cause.

SOIL HEALTH

Back in 2007/8 at the beginning of Jaff’s tenure on this farm, the cane was so poor that the cutters struggled to make stacks (for non-cane farmers, these are the bundles that the cane cutters build when harvesting the cane). As part of figuring out what was compromising yield, Jaff was sending all the soil samples off for analysis and they were coming back with no lime or gypsum recommendations. He found this odd as cane is known to drain the soil of this resource and decided to try a different laboratory. Bingo! The acid sats were off the charts – 50 to 70%! He was surprised anything was growing. He then began a long journey of correcting the imbalances and addressing the dire shortage of calcium in the soil. The sheer volume and associated costs of the lime necessary to fix the damage meant that patience was essential. He applied up 7 tonnes/hectare in some fields, with a further top up 2 years later. Twelve years down the line, the acidity is down to about 20% in the cane fields and Jaff aims for 0% acidity in mac orchards. This area is notoriously steep making lime applications challenging and even more expensive than normal.

Correcting the soil acidity has seen a marked turn around in the cane yield and quality; together with the difference that new cultivars and improved fertilisers have made, Jaff has a positive outlook for the future of cane on this farm.

Soil acidity and pH are a topics that have confused/intrigued me since the Sugar/TropicalBytes journey began. I am probably alone but, just in case there’s anyone else who would appreciate a little discussion on the causes and implications, here it is …

Soil pH

Soil acidity is measured in pH units. Soil pH is a measure of the concentration of hydrogen ions in the soil solution. The lower the pH of soil, the greater the acidity. pH is measured on a scale from 1 to 14, with 7 being neutral. A soil with a pH of 4 has 10 times more acid than a soil with a pH of 5 and 100 times more acid than a soil with a pH of 6.

Aluminium toxicity

When soil pH drops, aluminium becomes soluble. A small drop in pH can result in a large increase in soluble aluminium. In this form, aluminium retards root growth, restricting access to water and nutrients (see graph and picture below).

Roots of barley grown in acidic subsurface soil are shortened by aluminium toxicity.

Roots of barley grown in acidic subsurface soil are shortened by aluminium toxicity.

Nutrient availability

In very acid soils, all the major plant nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sulphur, calcium, manganese etc) may be unavailable, or only available in insufficient quantities. Plants can show deficiency symptoms despite adequate fertiliser application.

Microbial activity is also adversely affected by low pH in topsoils. Microbes are essential in turning organic matter to nutrients accessible to the trees.

Causes of soil acidity

Soil acidification is a natural process accelerated by agriculture. Soil acidifies because the concentration of hydrogen ions in the soil increases.

This happens when:

- Fertilisers are used ineffectively. Ammonium based fertilisers are major contributors to soil acidification. Ammonium nitrogen is readily converted to nitrate and hydrogen ions in the soil. If nitrate is not taken-up by plants, it can leach away from the root zone leaving behind hydrogen ions thereby increasing soil acidity.

- Plant matter is removed from the soil. Which is why we farm – to remove the produce and sell it. Plant material is slightly alkaline – constantly removing it increases residual hydrogen ions in the soil. Over time, the soil becomes more and more acidic.

Management of acidic soils

Management is based on knowledge. Knowledge is acquired by accurate testing.

- Because acidity is not uniform across large areas, you should take soil samples from a number of places and keep accurate records of where they came from.

- Testing QUALITY has to be the best:

- Ideally, soil samples should be taken when soils are dry and have minimal biological activity.

- Ensure that the solution used does not skew the results: It is standard to measure pH using one part soil to five parts 0.01 M CaCl2. Soils with low total salts show large seasonal variation in pH if it is measured in water. pH measured in water can read 0.6 – 1.2 pH units higher than in calcium chloride (Moore et al., 1998).

- Soil sampling should take soil type into consideration. For example, clays have greater capacity to resist pH change (buffering) than loams, which are better buffered than sands.

- Samples should be taken from varying depths to determine a soil pH profile. This will detect subsurface acidity, which may underlie topsoils with an optimal pH.

- Sampling should be repeated so that you can detect changes and allow adjustment of management practices.

Agricultural lime is the most economical way to maintain or recover the correct pH level. Limesand, from coastal dunes, crushed limestone and dolomitic limestone are the main sources of agricultural lime. Carbonate (from calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate) is the component in all of these sources that neutralises acid in soil.

The amount to be used will depend on:

- pH level of the soil

- Quality of the lime. This is based on the percentage of pure calcium carbonate and the particle size.

- The neutralising value of the lime is expressed as a percentage of pure calcium carbonate which is given a value of 100 %. With a higher neutralising value, less lime can be used, or more area treated, for the same pH change.

- Lime with a higher proportion of small particles will react quicker to neutralise acid in the soil, which is beneficial when liming to recover acidic soil.

- Soil type

- Farming system

- Rainfall

MULCHING

Jaff believes in adding as much organic matter as possible to the soil. As a result, the soils are rich and healthy – and that’s not my opinion, I consulted the experts:

For me, the presence of earth worms is an immediate tip-off to the health of the soil.

For me, the presence of earth worms is an immediate tip-off to the health of the soil.

All prunings are mulched in the interrows. Jaff is currently looking at a side-discharge mower/mulcher that will send the mulch under the trees. Home-made compost, comprising husks, cane trash and chicken litter, is also distributed under the trees annually. He also uses the interrow space to generate beneficial organic matter for the soil – sugar cane (the trash is left in the orchard) if the soil is of a higher clay content OR a mix of sunhemp, forage sorghum, sunflower (all good for bees and wind) and oats (for soil stabilisation) if the soil has less clay and needs more organic matter.

PEST MANAGEMENT

Straight out of the blocks, Jaff warns to stay away from calendar spraying. He showed me 2 posters, from 2 different chemical suppliers, who both suggest calendar-based ‘group’ sprays. These advocate combining a number of chemicals in each spray, applied at pre-determined intervals. Scouting is not a part of this plan and therein lies the danger. Please refer to the recent PEST MANAGEMENT article for more on this topic.

He has a well-trained scout who walks the orchards and records all his findings from the traps (these are hung for both Macadamia Nut borer (MNB) and False Coddling Moth (FCM). Every second week, they spray select trees and record the results. Jaff has decided to aim for an unsound rate of 2 to 3%, accepting that there will always be some damage when you run a soft-approach to pest management. His tolerance is tempered by the fact that the nuts on this farm are generally of a very high quality. He is concerned that, when the Beaumonts come in to production with a lower quality nut, that he may be tempted to lower his tolerance for pest damage to compensate, but that bridge is yet to be crossed.

When insect numbers climb, he sprays but is always cautious about what is sprayed, paying particular attention to resistance being built in the mac insects. Last season they had to spray 5 times, but ensured that each spray was a different active ingredient thereby lowering the chances of resistance.

Jaff suggests that farmers keep a close eye on their scouts to make sure the scouting standard is kept high.

When I asked Jaff which insects caused him the bigger headache, he found it difficult to compare – stink bug damage is largely “invisible” and you find out about it when your delivery is tested by the processor. Macadamia nut borer damage can be identified (and removed) during the sorting process on the farm.

Thrips damage is up and down. Last year was bad but this year there’s been nothing. 3 years ago Jaff learnt a hard lesson when he sprayed for Thrips when he shouldn’t have and (he believes) caused a mealy bug outbreak. This taught him a valuable lesson in caution and the consequences of poorly timed / unnecessary chemicals and how they can have expensive knock-on effects in nature.

Jaff believes his excellent quality is largely due to his carefully considered spray programmes – tree penetration and height are important parts of this and help him combat resistance issues. Well-maintained orchards that enhance spray penetration will lead to fewer sprays which leads to higher efficacy. Jaff has seen (and smelled) the number of stink bugs that come down when they are pruning tree height. This is enough proof that stink bugs chose to shelter in this part of the tree, where chemical saturation is lowest. Instead of lowering the trees and improving penetration in the higher branches, some farmers will simply increase spray volumes – Jaff cannot fathom the logic of this.

There was no shortage of life in Jaff’s orchards but I found the Lacewing eggs on stalks most fascinating (second from the left). I consulted Dr Colleen Hepburn who explained that Lacewing nymphs are predators and eat soft bodied insects such as mites, thrips, aphids etc. “If you see their eggs in the orchards, it means that the farmer does not use harsh chemicals too heavily, which is always a bonus,” clarified Colleen.

There was no shortage of life in Jaff’s orchards but I found the Lacewing eggs on stalks most fascinating (second from the left). I consulted Dr Colleen Hepburn who explained that Lacewing nymphs are predators and eat soft bodied insects such as mites, thrips, aphids etc. “If you see their eggs in the orchards, it means that the farmer does not use harsh chemicals too heavily, which is always a bonus,” clarified Colleen.

Jaff is always mindful of what sprays will affect his bees and which time of the day works with their schedule. He watches the temperature as bees tend to get active only after 16,5°C, leaving the cooler early mornings or nights as spray options. Jaff has noted that swarms are becoming increasingly scarce and invests what he can in protecting what he has.

The bees are given the reverence they deserve on this farm.

The bees are given the reverence they deserve on this farm.

Phytophthera: 1 to 2 months after planting, Jaff applies the first treatment against phytophthera, regardless of whether or not symptoms are showing. He uses Phosphite fungicide 400, 40% product 60 % water, painted onto the stems below the graft union. Thereafter, Jaff sprays the stems of all the trees, across the farm, every year. He has a special ox-horn sprayer that I had never seen before. It has 3 nozzles that circum-surrounds (not sure if this is a new word I just made up but it works 😊) the tree. Whilst doing the annual spray, staff make a note of any unhealthy trees. Jaff then inspects those himself and they will be put on a schedule to receive additional applications and monitoring.

The phytophthera sprayer has 3 sprays that apply chemical to all sides of the tree stem in one go. It is fed by a knapsack tank.

The phytophthera sprayer has 3 sprays that apply chemical to all sides of the tree stem in one go. It is fed by a knapsack tank.

I had never heard of ants being a particular issue but Jaff had an illustration of how they can cause serious damage and have stunted this tree’s growth considerably.

I had never heard of ants being a particular issue but Jaff had an illustration of how they can cause serious damage and have stunted this tree’s growth considerably.

Although this is a beautiful photo, it does show fungal damage at the tip of the raceme. Jaff does use fungicides as fungi are a challenge in this highly humid environment. He is happy to see that the fungus was clearly stopped before it caused any significant damage.

Although this is a beautiful photo, it does show fungal damage at the tip of the raceme. Jaff does use fungicides as fungi are a challenge in this highly humid environment. He is happy to see that the fungus was clearly stopped before it caused any significant damage.

HERBICIDING

Jaff is not interested in maintaining a manicured farm at the expense of soil health (and consequently, yield). Every decision is made with the health of the crop in mind. He makes sure he knows what every chemical he applies is, how it works and what the environmental impact is. He’s always believed that glyphosate does not travel through the soil. I have also heard many farmers tell me that this chemical becomes inactive as soon as the plant dies. While this has never made sense, the farmers are usually fairly insistent.

Jaff has learnt, the hard way (why does it always have to be hard?), that this chemical does in fact move through the soil. The hard lesson came when he had a team of ladies spraying the grasses around the young macs. They are well-trained, experienced woman who Jaff trusts with his precious youngsters.

When Jaff noticed the macs on a hilltop were struggling, he began investigating. Much head-scratching later, he tied it back to a glyphosate application and almost lost it! His number one sprayer was demoted, despite her promises that she did not go anywhere near the trees.

Glyphosate damaged trees, worse at the top of the hill, where soils are sandier, than at the bottom, where there is a much higher clay content.

Glyphosate damaged trees, worse at the top of the hill, where soils are sandier, than at the bottom, where there is a much higher clay content.

But, the damage continued, despite having a new sprayer. He also noticed how the damage was worse where the soils are sandy. More investigations. Ultimately, Jaff has concluded that the glyphosate did indeed travel through the soil. As with everything else, it moves better through sandy soils and less so through heavy clay. Apologies and reinstatement for the sprayer. More careful use of herbicides. While no trees were lost in the learning of this lesson, it did cost at least two years of growth!

As always, I could have stayed here forever. In fact, Jaff offered me accommodation …

So kind!

So kind!

I’m fairly thick-skinned but even I know when it’s time to leave. I am extremely grateful for all the time he spent with me and for all the insight I have been able to share. Sincere thanks is also due to the valued sponsors of this article – Kynoch.

And credit to the site from which I gleaned much understanding about soil acidity …

Keep safe on the Corona-coaster.

See you again in September.