Sometimes my ignorance (or lack of knowledge) terrifies me. Especially as the readership, and intrigue, in TropicalBytes grows. I am overjoyed at the opportunity to inspire through the experiences of others but simultaneously burdened by the responsibility to deliver useful, practical information that will make a positive difference. The terror is good – it fuels the determination to continuously learn, improve, and seek out the very best in the industry to build the content of these pages and deliver it in the most helpful way.

So, going forward, three ways in which I am going to put those words into action are:

- Create Context for the Content. In order to pay my bills (nope, TropicalBytes is still a way off from doing that) I contract some of my time to an incredibly progressive and unique corporate. Their Founder is an inspiring man who has taught me the profound relationship between Context and Content. You cannot meaningfully discuss Content until you have set Context. So, as a simplified example, diving into how fertiliser is applied on a particular farm (content) is pointless unless you have an idea of how large that farm is (context).

Context is set, not only by the physical attributes of a farm (like those I usually specify in the table leading into each article) it is also largely based on who the farmer is: does he have to accommodate the whims of a “retired” dad who still lives on the farm. Does he prefer fishing to farming and therefore day-dreams of Bass, not Beaumonts. Or perhaps he is living under a land-claim, making decisions he wouldn’t if he had the luxury of a longer-term strategy. Or perhaps he has a passionate drive to conserve the environment so that his grandchildren will live to enjoy the services of bees. But maybe he is a farm manager, reporting to a foreign investor, who judges him on bottom lines, not butterflies.

Going forward, I am going to do my best to set meaningful Context through which you can view the Content and thereby be more astute in how you can apply the learnings to your operation.

- Clarity on quantity: when I say 4 tonnes per hectare, your interest may be peaked but, when I clarify that it is pre-husked, 15 year old Beaumonts, off an orchard planted at 7m x 4m spacing, your reaction is different. I do not believe that, in the past, I have given enough clarity when discussing quantity which has reduced the relevance of mentioning those figures at all. I will change my ways. 😊

- Broaden the scope: I am making a concerted effort to engage with as much of the macadamia industry as possible and that includes all macadamia processors with the aim of further broadening this platform and thereby delivering a well-rounded and broad-based perspective on everything related to your macadamia farming excellence. Being an introvert deep down, that isn’t always easy, especially when people are usually (and often justifiably) suspicious of what it is you REALLY want from them. It’s just not conceivable that your main aim is to celebrate and inspire excellence in farming. (Okay, I would, one day, like the venture to fund itself, but I believe that will happen ONLY once objective 1 has been attained). So, I donned my proverbial big girl panties and began extending my reach. Thank you to all those processors who have been wonderful in opening up to TropicalBytes and seeing the value it offers the industry. Jaff 8 was found in this process.

Like so many top farmers, he was reluctant about my visit; wary of the spotlight and the insinuation that “he knows more”. But, good nature and wanting to help others, through any value his experience may impart, won over and I found myself beetling up the N2 one beautiful KZN Monday morning.

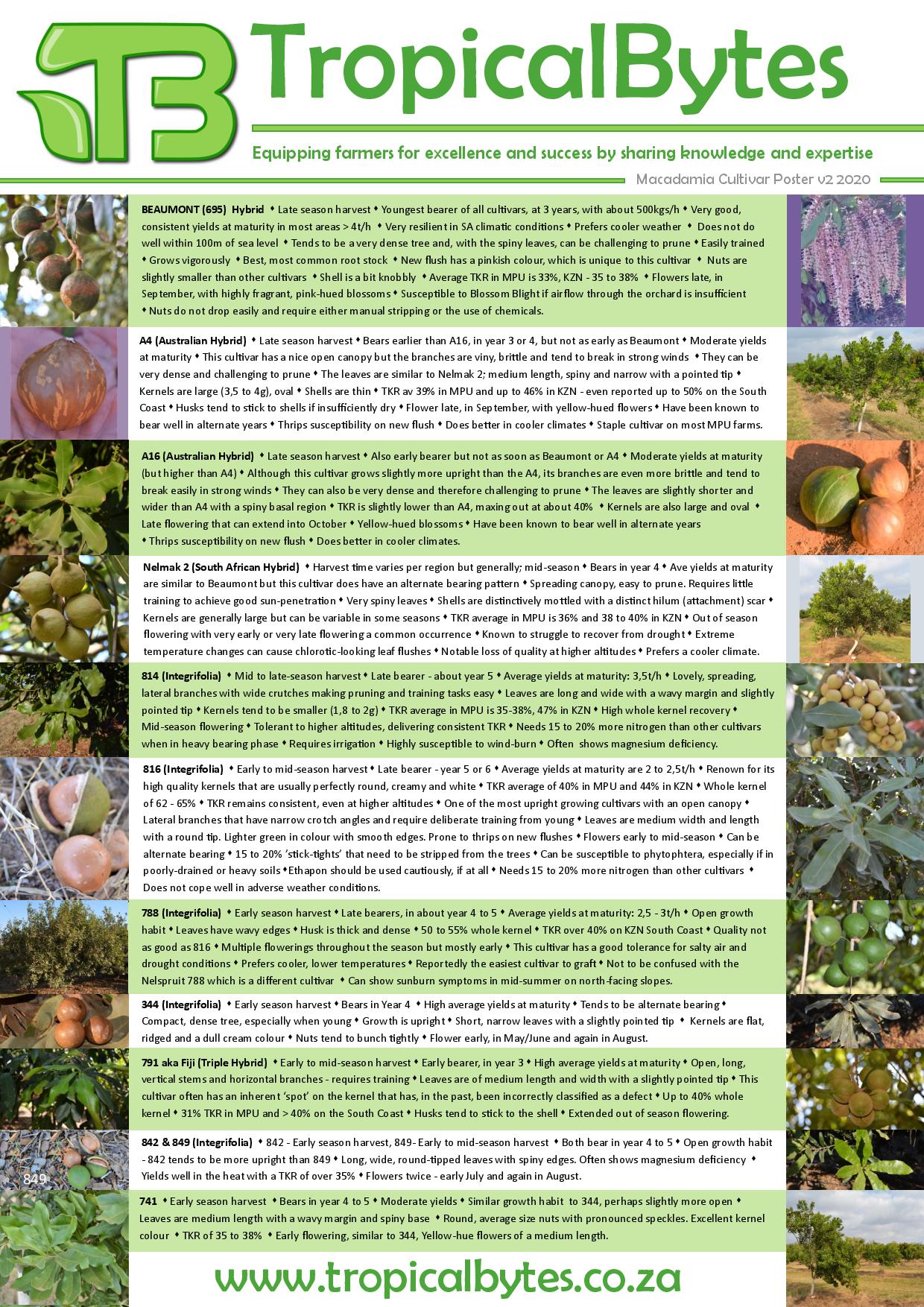

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date | 20 January 2020 |

| Area | Kearsney, (near Stanger, now KwaDukuza) KZN North Coast |

| Soils | Poorly drained sandy soils |

| Rainfall | Just less than 1000mm annually |

| Altitude | Ranges from 230m to 390m (290m) |

| Distance from the coast | 10 kms (as the crow flies) |

| Temperature range | 10 to 32°C |

| Varieties | Beaumont – 20ha, 788 – 20ha, 816 – 35ha and 814 – 15ha |

| Hectares under mac | 90ha (85ha bearing currently) |

| Other crops | None |

The mac farm we are covering today has trees of varying ages but most are now in production. The oldest are 14 years. Jaff joined this operation 10 years ago and therefore missed the planning and establishment stages. Living with this farm has taught him what he would do differently if he had been involved during those critical phases.

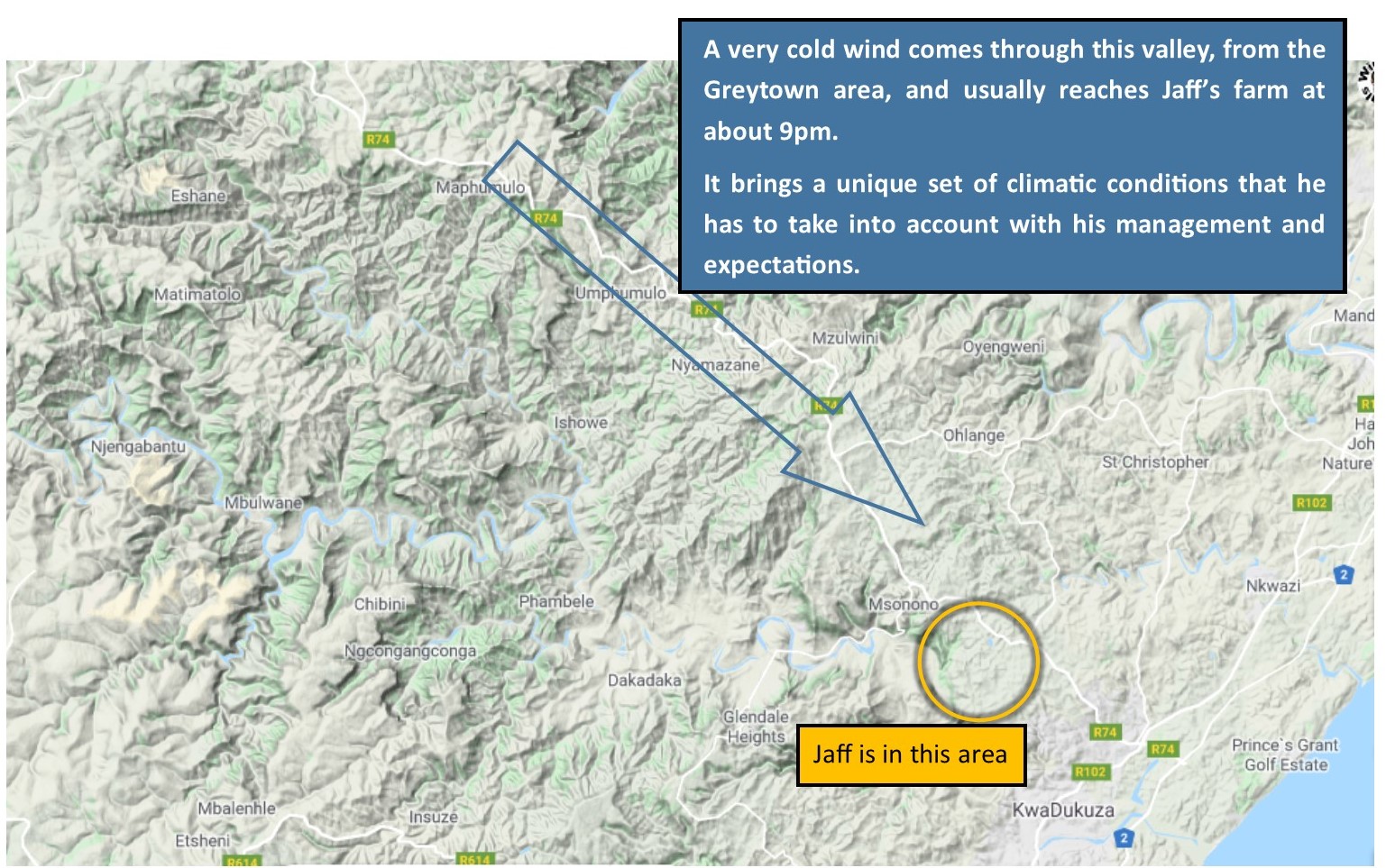

The Umvoti river creates the border on one side of the farm. In winter, conditions can turn very cold. When temperatures drop in Greytown the air sinks through the valley and replaces the warm air with very cold air, usually at about 9pm. It drops to about 10 to 12 degrees but the wind chill is freezing. On the farm next door, there’ll be not a breathe of wind, but, on this farm, it is a freezing-cold gale. Jaff is aware that everything from insects and fungi to tree growth and nut development must be affected by this chill.

FARMER CONTEXT: Jaff’s journey has been typical of many great farmers; he grew up on a cane farm (or in the boarding school he attended from young – depending on the way you look at it). His dad was a farm manager. His post-school expeditions took him into farming equipment sales and eventually, 14 years ago, back into farming. This time, in macs.

Despite the hard-outer veneer, Jaff is actually a very open and inquisitive man who encourages interaction with, and creativity from, his staff. Being in a management position (as opposed to owning the farm) has it’s challenges and it’s blessings but Jaff is grateful for where he finds himself and has realised great success – if he hadn’t, I wouldn’t be sitting next to him right now. 😊

He has a passion for conserving the environment but has to balance this with delivering healthy bottom lines for the farm’s owners. One of the reasons his processor recommended him for a TropicalBytes’ interview is because of his exceptional sound kernel recoveries which is impressive, given that he is very reluctant to use anything harsh on the farm and is currently trialling a number of bio-solutions (products that have been formulated with the greater ecosystem in mind).

He is a divorced father of two (almost grown) boys who are the centre of his world – unless you are the farm-owner reading this, then your farm is the centre of his world. 😊

For the past 2 years, Jaff has delivered an annual total of 253 tonnes, DIS at crack out. That’s almost 3 tonnes per hectare average, across all cultivars and tree ages. And, the majority of his farm is the notoriously low-bearing 816. But the impressive part is that he has been an award winner MANY times over for his low unsound kernel levels, so, with that Context, I think it is worth paying attention to the Content …

LAND PREP AND ORCHARD PLANNING

One interesting feature of this farm is that there are only 4 cultivars and no orchards are dedicated to a single cultivar – the 788s and 816s cohabitate and the Beaumonts are planted together with the 814s. Although he believes cross-pollination is vital, he wouldn’t recommend this strategy to achieve it. It makes catering for unique cultivar requirements expensive and challenging, eg: nutrition requirements and harvest strategies differ between cultivars; by having them in one orchard you end up going into that orchard multiple times to cater to these unique needs which obviously doubles the resource requirement (time, equipment, staff) that uniform orchards would have. It also opens up opportunities for mistakes as staff do their best to address the differing requirements and timings within each orchard.

It is Jaff’s advice that you plant smaller fields (just over a hectare) with one variety, and try to keep the block within one soil type. Cross-pollination can be accommodated by having suitable cultivars planted in neighbouring fields.

Jaff has learnt, the hard way, of the value of wind-breaks. In some areas, they’re an integral part of planning a new orchard. “Casuarinas are good and they grow quickly. Napier fodder is also okay but be cautious of its combustibility,” comments Jaff whilst also reminding us that whatever you choose carries a cost in terms of timing (must sometimes be put in years before the macs) and investment. He also warns against cutting corners in mac farming, “It may come back to bite you.”

Jaff feels that this particular farm would have benefitted tremendously from ridges. The soil is very sandy with an underlying layer that hinders effective drainage. The fields should have been ripped extensively to break through and incorporate the clay layer below and then ridged to maximise the drainage around the tree roots. At this stage, Jaff tries to remedy the situation by ripping the interrows. He did this about 4 years ago, to a depth of about 800mm, with a winged tool that turned open a nice furrow. Into this he placed as much organic matter as he could. This exercise marginally relieved the drainage issue but it also added valuable organic matter to the soil profile. This food source encouraged lateral root growth. His soil experts would like it to be done again this year but he is cautious because of the erodibility of the soil and the high chance of unpredictable heavy rains. The sand here is very fine, so much so that some have suggested Jaff make cement rather than grows trees. Jaff says that when the rippers past through the soil, it screamed as though being dragged through concrete. (I bet a fair number of you are sending up silent prayers of thanks for your “bad” soils right now?)

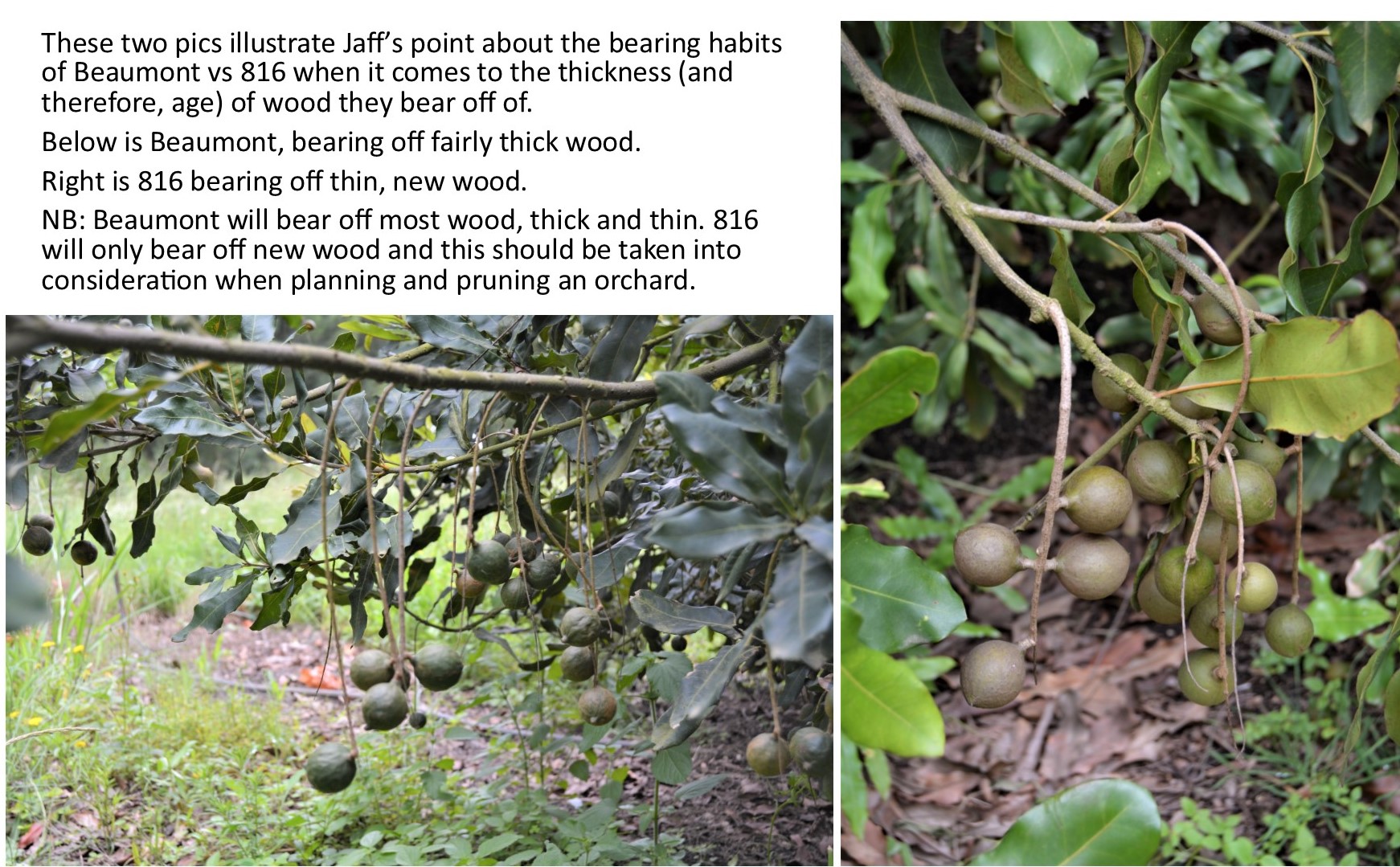

These orchards are planted at 10m x 5m. A consequence of this wider-than-normal spacing is that you take longer to “reach production” but Jaff explains that this short-term negative is outweighed by the long-term value of light and unobstructed access in a mature orchard. Jaff explains that the value of this space differs per cultivar; 816s bear on new wood, and bearing wood is maximised on a bigger tree. Beaumonts will bear on thicker wood and therefore a bigger tree is not as important. The absolute minimum Jaff would go on spacing any orchard is 8m x 5m. “Sunlight between trees in a row is as valuable as sunlight between rows.”

These trees get plenty of sunlight and the sprayers are not impeded by interrow growth. Notice also how low the skirts are, which helps to keep the roots sheltered from the hot sun and the soil moist. Jaff doesn’t “clean up” under these skirts so there is lots of natural mulching – further enhancing the environment for healthy root activity.

These trees get plenty of sunlight and the sprayers are not impeded by interrow growth. Notice also how low the skirts are, which helps to keep the roots sheltered from the hot sun and the soil moist. Jaff doesn’t “clean up” under these skirts so there is lots of natural mulching – further enhancing the environment for healthy root activity.

“Interrow spacing cannot go under 8m as you need at least 1m on either side of a tractor as it passes through to spray,” is Jaff’s advice.

As far as settling a young tree in, Jaff suggests the use of biologicals in the hole when planting. He is currently trialling some new options.

CULTIVARS

The 90 hectares on this farm are split between 816 (just over 40%), Beaumonts and 788 (each at just under 25%) and the remainder is made up of 814s.

Jaff submitted some impressive pics. I even got one of a really large fish – think he had accessed his “bragging folder” 😊

Jaff submitted some impressive pics. I even got one of a really large fish – think he had accessed his “bragging folder” 😊

788 and Beaumonts are the poorest producers with both quality and yield being below his expectations. Although Jaff has managed to lift the yield from 2 to 3,5t/ha (DIS at crack out), Beaumonts have the lowest net income per hectare and you can hear the disdain in his voice whenever he mentions this cultivar. When I asked him about this he says that he is starting to believe that THIS farm is just not suitable for Beaumonts; perhaps it is the proximity of the ocean (just 10kms away) although the farm’s altitude falls above the recommended no-go area for this cultivar. He is not sure what it is but he can’t seem to excel within 695.

Jaff has noticed changes in the results and behaviours of 814 particularly as the farm matures. These trees are moving to a later harvest and are quickly becoming the best in terms of sound kernel recovery. There are a number of factors that could be behind the changes; being interspersed with the Beaumonts might be pushing their harvest a little later. Installing a second irrigation pump enabling more regular irrigation might also be working well for this thirsty variety. It may also just be that they are only now recovering from a severe hail storm (three years ago).

816s have always been the best performers but, at 4.7t/ha DIS at crack out, the 814s are taking the lead.

NUTRITION

Effectively interpreting soil results and administering relevant nutrition is an area that Jaff feels he has most room for improvement in. He is acutely aware that there are profiteers out there, trying to promote their products, regardless of what you need. He hopes he has found a reliable partner in this arena and is committing to trust their advice.

Soil analyses are done twice a year (in October and again in March) and appropriate corrective nutrition is applied keeping yield expectations in mind. Jaff is uncomfortable that the orchards get this fertiliser as a standard, considering that there are always two cultivars in each block. He does his best to address this by sometimes only using one side of the sprayer in applying foliar feeds, thereby custom-feeding each variety. This sometimes necessitates two trips into the orchard which is double the resource requirement, as mentioned earlier.

Jaff explained that leaves give excellent clues as to what the tree is lacking; green veins with yellow in between is an indication of an atmospheric-based issue like herbiciding. Yellow veins and green in between is an indication of a problem coming from the soil, like a toxic build up. Yellow all over the leaf is often a deficiency, like iron.

Jaff explained that leaves give excellent clues as to what the tree is lacking; green veins with yellow in between is an indication of an atmospheric-based issue like herbiciding. Yellow veins and green in between is an indication of a problem coming from the soil, like a toxic build up. Yellow all over the leaf is often a deficiency, like iron.

816s are always quick to tell you if is lacking something. 814 is a bit tougher but will show deficiencies, eg: at this time of the year it seems to present signs of magnesium toxicity. Jaff verified that 816 and 814 do need more nitrogen than other cultivars.

Foliar feeds are an area in which we all have so much to learn but Jaff highlights a few instances in which it may be helpful:

- With these sandy, poorly drained soils, 100mm of rain will turn most of the farm into a swamp. This rain leeches the soil terribly and Jaff therefore uses a lot of foliar feeds to correct trace element deficits. Eg: zinc, boron, copper, magnesium, and calcium.

- Another instance in which foliar feeding would be recommended by Jaff is when a mineral is not, for whatever reason, being taken up from the soil. Adding more and more of that mineral to the soil will only create an imbalance, so avoid that by trying a foliar application.

- Foliar feeds are a quick fix – they are not going to help your soil profile or health, which is vitally important but they will help the tree cope while you attend to the soil issues.

When I enquired as to why many farmers were sceptical of foliar feeds, Jaff explained that finding the right adjuvants to combine with the feeds is challenging and can lead users to believe the foliar feed doesn’t work. Foliar feeding is a science that needs to be trialled, and adjusted rather than abandoned. Other products like kelps are also very interesting and can be used as a foliar feed carrier. This is available in varying qualities and, again, needs to be trialled and tested in your environment.

Nice rich compost, maturing for use.

Nice rich compost, maturing for use.

Jaff emphasises that there is so much “nonsense” (my nice word for what he said 😊) coming from chemical companies and farmers need to be very careful. “You need to do your OWN homework; sift through the options, compare the concentrations, prices and ingredients. Constant testing, IN YOUR OWN ENVIRONMENT is key. Don’t copy the neighbour.” Jaff also warns against writing something off forever, “Remember that products are improving constantly eg: a chemical or supplement may be improved in terms of its droplet size and therefore be better absorbed than the last time you tried it. Never stop testing.” He adds, “You also need to trust some people – choose a supplier you feel you can work with and lean on their expertise. Build a relationship with them so that you get the service you need. Sometimes a late delivery can spell disaster so good management and team work with suppliers is vital.”

Although it is still largely an aspiration, Jaff is trying to go more “green” in his fertiliser profile and is getting excited about harvesting the trial blocks, where he has been using new things like silica, this season. He first started applying silica in January 2019. The orchard had had one application by the time it was harvested in April, and the sound kernel had increased by 3%. He is not sure about the science behind it (or even that all this improvement was solely due to the silica) but suspects that it may have improved cell division.

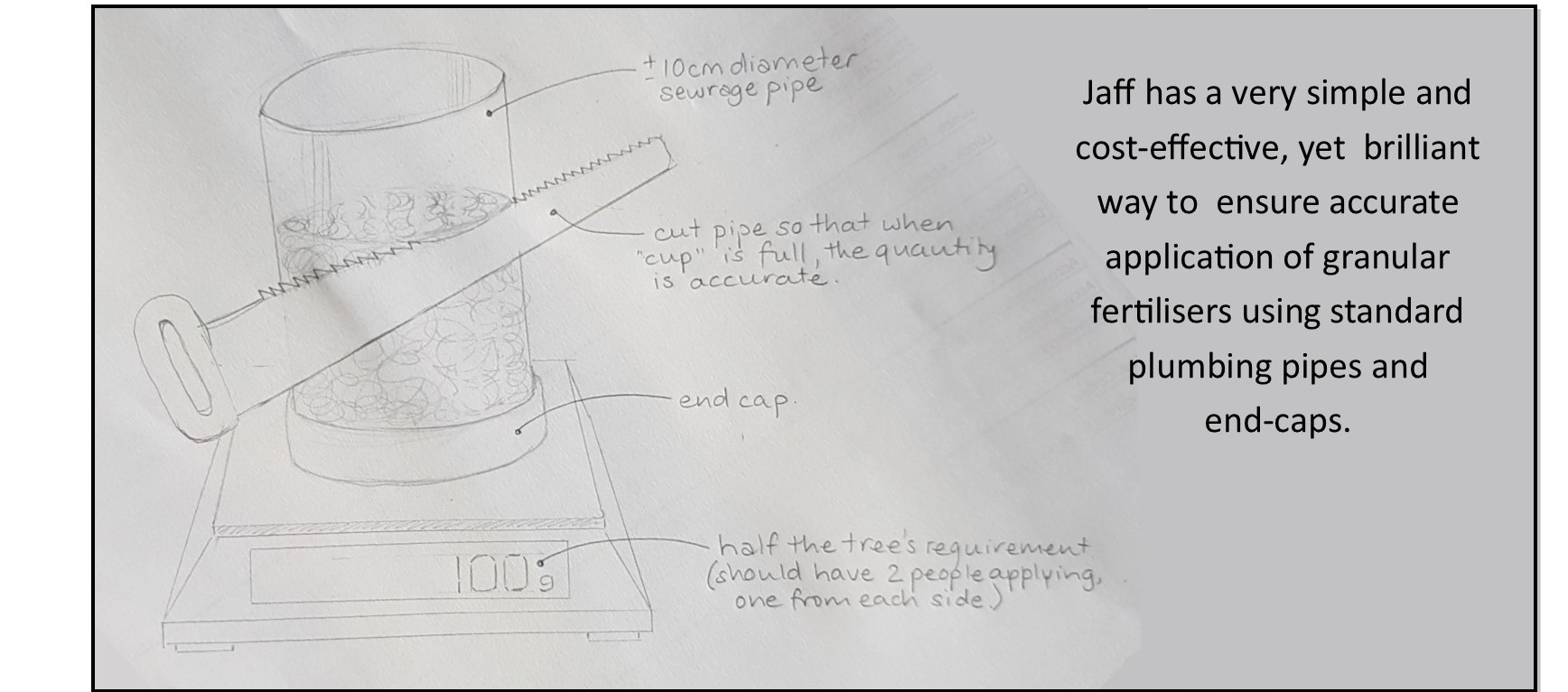

Jaff applies supplements in various ways, depending on the requirement and the environment, as covered above briefly in foliar feeding. Generally though, he uses granular fertilisers, applied by hand.

When using labour to manually apply fertilisers, Jaff says that using smaller groups, focussed on accuracy pays off. Check up on them to ensure that what you think is happening, is actually happening. Jaff emphasises that this simple exercise of checking is more often than not, the difference between success and failure.

When it comes to some of the more unstable biologicals, Jaff uses fertigation through the microjets by plugging in a 145l “kettle”.

When it comes to some of the more unstable biologicals, Jaff uses fertigation through the microjets by plugging in a 145l “kettle”.

MOISTURE MANAGEMENT AND DRAINAGE

As mentioned, this farm has predominantly poorly-drained, sandy soils, making moisture management a science. Of course, he needs rain to fill the dams but more than 70mm at once gives him a headache. He finds it easier to farm in dry conditions when moisture can be controlled through irrigation. Heavy rains are not manageable and affect the trees adversely. The drier the weather, the better these trees look. Now that they are older, they manage wet phases better. Jaff loses trees to wind, phytophtera, and even lightening, but never to drought.

Jaff believes that microjets are the best way to deliver the required water to the mac trees. The heads need to be changed as the tree matures and it is important to use the system in line with its design eg: place the jets 1,25m from the tree, one on each side is what he does.

Jaff does advocate mulching but it is not a major part of his strategy currently, primarily because of the scarcity and therefore expense of accessing this organic matter in volumes. What he has, he is saving in case he rips the interrows again this year. He also prefers not to put it down before harvest.

One of the first things Jaff stopped when he got to this farm was the use of glyphosates. He also does not “clean up” under the trees and there is therefore a fair bit of natural organic matter present (leaves etc). There are two dryland orchards on the farm that are at the highest elevation points on the farm and did not warrant the expense it would have taken to install irrigation to them. He always tries to ensure that these orchards are well-mulched.

One of the first things Jaff stopped when he got to this farm was the use of glyphosates. He also does not “clean up” under the trees and there is therefore a fair bit of natural organic matter present (leaves etc). There are two dryland orchards on the farm that are at the highest elevation points on the farm and did not warrant the expense it would have taken to install irrigation to them. He always tries to ensure that these orchards are well-mulched.

PRUNING & TRAINING

Jaff explains that, after ensuring that there is sufficient sunlight and sprayer access, pruning becomes very cultivar specific. Because Beaumonts bear on old as well as new wood, are naturally a more ‘closed’ tree, and they can suffer from air-flow related challenges (like the fungus Blossom Blight) they can be pruned more aggressively. 816s, on the other hand, bear on new wood and therefore need to be trained more, as opposed to pruned harshly.

He has found that if 816s are managed correctly, they will exceed previously stated yield and bearing age averages. He has had 2,5t/ha (DIS at crack-out) off 6-year-old 816s and he puts most of this result down to effective pruning and training. So, what’s the secret? “Train them to grow outward,” says Jaff, “naturally, they want to go up all the time.”

Jaff uses these reusable, easily removable plastic forks to train his trees. He finds they are perfect in the strong winds he faces here, as the forks will simply pop out before breaking the tree. This is not always the case when tying a tree down.

Jaff uses these reusable, easily removable plastic forks to train his trees. He finds they are perfect in the strong winds he faces here, as the forks will simply pop out before breaking the tree. This is not always the case when tying a tree down.

Another ingenious training strategy Jaff uses is to staple the young, pliable trees. Yes, you read right – he staples them! He says this works well to gently open a tree and lasts long enough to make a meaningful difference without any damage or excess labour incurred. In the picture above he shows where he would staple and how significant the effect is.

Another ingenious training strategy Jaff uses is to staple the young, pliable trees. Yes, you read right – he staples them! He says this works well to gently open a tree and lasts long enough to make a meaningful difference without any damage or excess labour incurred. In the picture above he shows where he would staple and how significant the effect is.

Because 814s are naturally more open than 816s, Jaff feels they do not need as much work. In fact, he advises that you need to be careful with the clippers in these orchards. This comes from an experience of seeing 814s knocked back and how long they took to recover: In about 2014/5 they had a severe hail storm and the 814s and Beaumonts were extensively damaged. The Beaumonts bounced back quickly but the 814s took about 3 years. Compounding their susceptibility to the hail damage is the fact that they are naturally very open trees.

In Jaff’s experience, 788s can take a fairly harsh pruning, they’re not as finnicky as an 816 or 814.

Jaff believes that it is best to prune as quickly as possible after harvesting. He prefers using his own men. He explains that mistakes in pruning are to be expected; the most common of which is to keep going, in an effort to “make it right” – before you know it, you’ve gone too far. To stay out of this trap, Jaff has set himself a rule: He only allows TWO cuts per tree per year and therefore has to decide WHICH two would be MOST beneficial to the tree that year. It usually comes down to removing any impediments to comprehensive spray access. Jaff consoles that, if you do happen to over-prune, it’s not the end of the world; in fact, you might well be rewarded with a boost in yield in the succeeding year. He just prefers consistent yields rather than variable successes.

He uses Japanese saws – technology that cuts on the push rather than the pull. Extender poles always come in handy as does the battery-operated chainsaw he sometimes uses for larger branches.

PEST MANAGEMENT

Jaff has been limited by the soils and climate of this farm (and he cannot change either of those) so he chose to focus on an area in which he felt he could “make more of a difference”. His sound kernel rates indicate that he’s worth listening to when it comes to pest management.

Jaff’s whole farming philosophy is based on farming with nature, not against it. He doesn’t believe you can completely break from chemicals but you can remain aware of the side-effects of your chemical use. To this end, Jaff ensures that:

- His chemical partner is on-board with his “green” approach.

- He only sprays at night. Not only does this reduce the volatilisation of chemicals, the cooler air also settles the spray into the tree and of course, bees should all be in their hives at this time.

Jaff uses a blue light at night so he can detect blocked nozzles quickly. The light clearly shows that the spray is staying in the orchard rather than being taken up as it would be in daytime temperatures.

Nut borer: Economically, nut borer is the biggest challenge Jaff faces. He hasn’t discovered how to deal with it but believes that it is mostly a timing game with this critter. You need to be ready to strike (equipment functioning) when the weather is right and the moth’s cycle is susceptible.

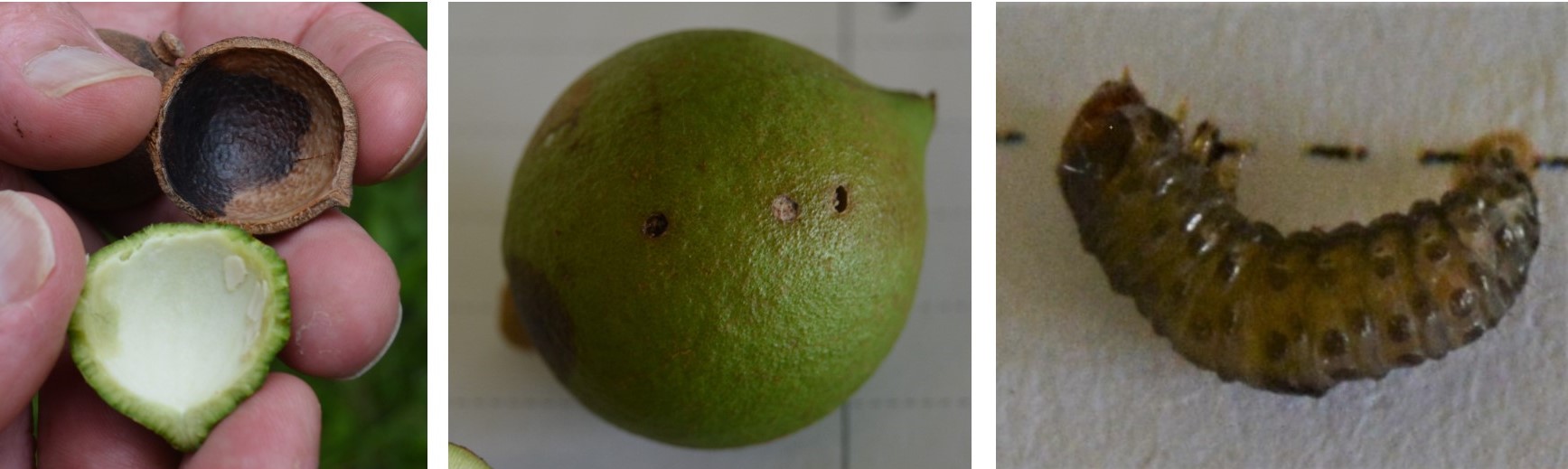

Jaff explains that the moth arrives and lays her eggs on the husk. The larvae emerges and then bores into the husk. If the shell is soft enough, he’ll keep going into the kernel. If it isn’t he’ll burrow around between the husk and shell, eventually creating such damage that the immature nut falls. Either way, your nut is gone if that larvae moves from his egg into the husk so the window is really small. Your chemical needs to be on the husk and active when the larvae emerges. Easy to see why Jaff feels that this is a tough adversary. Jaff has delta traps to try and monitor the count of these bugs but placement of these traps is important. Poor placement will give misleading results. Ie: windy areas.

If you struggle with nut borer, Jaff advises that you do not spray before the November dump. He believes the moths know that those nuts are going to fall and they won’t lay on them. But as soon as this event is over, spray because they will be there for the nuts that haven’t fallen.

Left to right: Comparing a healthy husk to one that has been depleted by a nut borer worm who didn’t get past the shell, evidence of the nut borer’s entry, the criminal (in worm form).

Left to right: Comparing a healthy husk to one that has been depleted by a nut borer worm who didn’t get past the shell, evidence of the nut borer’s entry, the criminal (in worm form).

Fungi: Two years ago SABI tested three sites in KZN. There were a total of 12 pathogens and this farm tested positive for all 12! Something about this farm makes it very susceptible to fungi. Besides Blossom Blight in the Beaumonts, lately he has also been struggling with Dry Flower blight in the same cultivar. This curse dries the whole raceme, whereas, in his experience, Blossom Blight only takes out the bottom third (-ish). Husk rot is another pathogen that he feels has been exacerbated by recent thrips infestations. When the thrips damage the husks, they create vulnerabilities for things like husk rot.

Stinkbugs: Jaff finds stink bugs easier to manage. Key in this war are two key practices:

- Making sure the chemicals are reaching the insects. This can be managed through proper pruning and well-calibrated equipment.

- Effective Scouting. Jaff has no idea how anyone manages pests, responsibly, without scouting. It is a vital task within his operation. Without it, he believes the only ones you are making happy are the chemical companies.

Jaff has split his farm into three parts and scouts each part three times every week. Here are some pointers on how he handles this task:

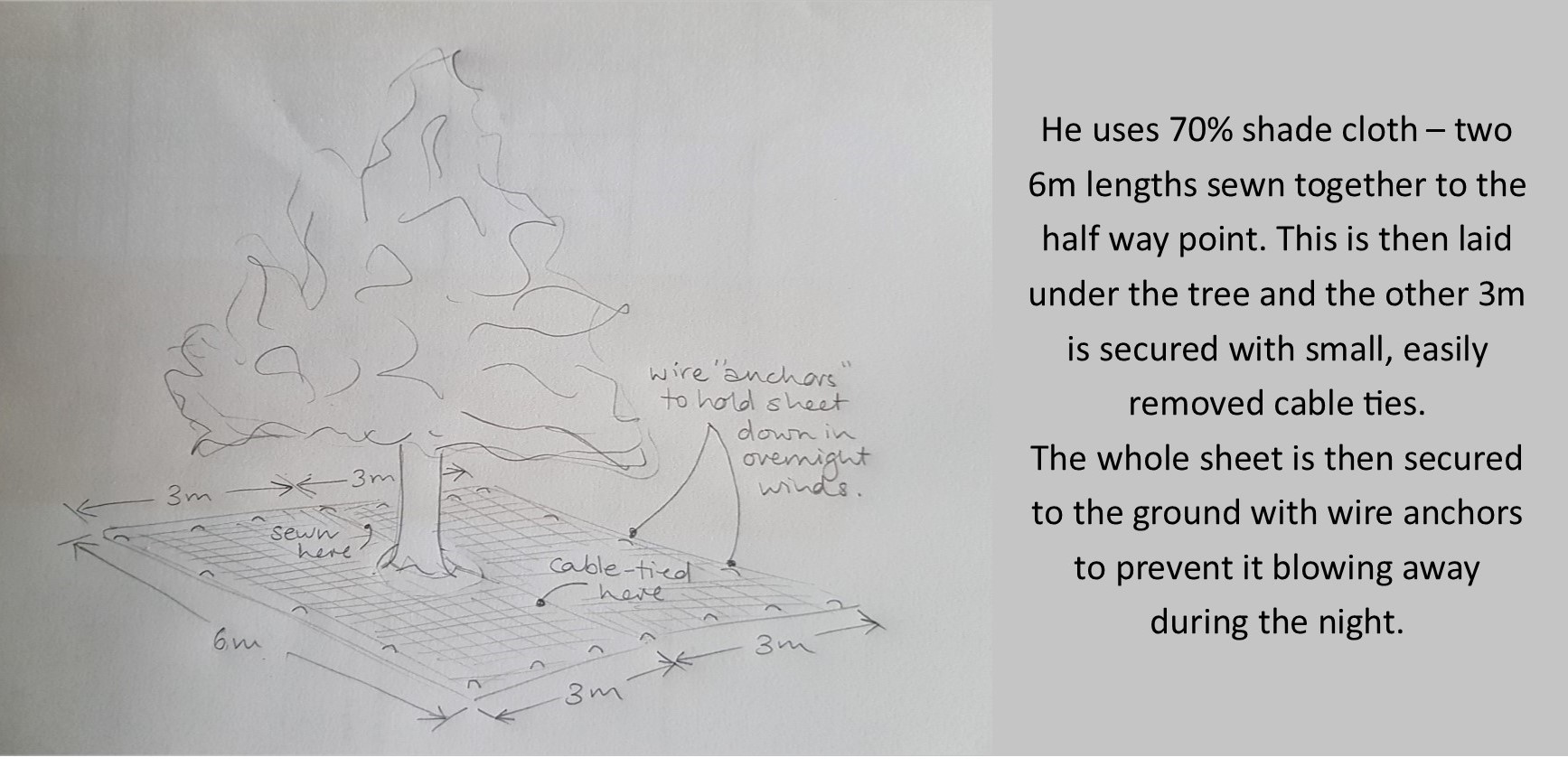

- The scouting team prepares the relevant sites the day before by laying sheeting under the designated trees. The trees and rows are marked so that locating them in the dark is easy.

- The next morning the team leaves long before dawn (in summer, that is at about 3H30 to 4H00) so that the insects are caught before they start moving.

- The tree is sprayed by hand off a 600l sprayer. Jaff explains that contained spraying in scouting is vital, ie: make sure that you are ONLY spraying the targeted tree with no overspray. The chemicals used in this practice are very harsh and stay in the environment for about a month. Broad spraying will therefore affect future scouts, especially if you are concentrating scouts in hot spots, as you should be. Jaff recommends that you get out there with the scouts and make sure that the spray is done properly, penetrating the tree effectively. People’s laziness can lead to inaccurate results and ultimately, the failure of your pest management.

- Scouts go back once the sun is up and collect the bugs and bring them back to Jaff who analyses and records the catch, making spray decisions off the numbers.

- If counts dictate a spray, Jaff gets it done the same day, after nightfall.

Hot spots are proven and Jaff emphasises the importance of scouting these regularly. Scouting will help you identify where your farm’s hot spots are. Knowing the location of these susceptible areas is key in effective pest control. Spend your scouting time wisely. eg: Generally higher, windier areas are fairly secure from insects so they require infrequent checks.

Traditionally there is two-spot (late season) and yellow-edged (early season) stink bug on this farm. Softer, biologic treatments are improving all the time, reducing the need for harsh chemicals. But Jaff warns to be vigilant in your scouting, treat the bugs you find, where you find them (ie: avoid blanket sprays). Use soft approaches for as long as possible.

Since Jaff has started using more eco-friendly products he has definitely noticed that there are more ladybirds, butterflies and birds in the orchards, indicating a healthier ecosystem inside the orchards. He even saw sunbirds in his flowering orchards this year. This kind of restoration would not be possible without the vigilant scouting he conducts, which mitigates a large part of the risk he is exposed to. Even when weekday weather is inclement, Jaff will extend the scouting into the weekend to ensure that no bases are left uncovered. If he wants to restore the natural ecosystems AND ensure the financial stability of the operation, he has no choice but to keep scouting as a top priority.

A nice close up of Brown Stink bug, captured by Jaff.

DISEASES

With these poorly drained soils I was not surprised to hear that Phytophtera is a problem here. Jaff uses a phosphoric acid-based product that he applies to the trees’ stems. The following day he paints a PVA + copper mix over the top. This is done annually regardless of the tree’s health or age, timed in conjunction with a root flush. These root flushes happen after a leaf flush, usually in Jan/Feb and again Sept/Oct.

GRAFTING

Now this is fascinating; Jaff has been trialling branch-grafting. The motivation is that he wants to maintain uninterrupted production whilst changing a cultivar. So, the 788s that Jaff would like to replace are having a low branch removed. He then grafts 814 budwood onto the severed branch. The rest of the tree is still producing 788 nuts but, eventually, the 814 will take over.

Although he is having success, he believes the long-term outlook would be brighter if the original root stock was of quality seedlings. Some on this farm were rooted cuttings and may not even be Beaumont.

HARVESTING

Jaff uses ethapon on the majority of his macs. The 816s, because of their highly sensitive nature, and some 814s that may not look up to the challenge, escape but all the Beaumonts and 788s are sprayed to encourage nut drop. Having interplanted varieties make this exercise challenging but Jaff sees value in being able to schedule the harvest and move in swiftly to get pruning done before flowering starts.

Jaff tries to ensure that all nuts are collected within a week of being stripped from the trees. The pickers’ collection is recorded by crates and emptied into half-tonne lug baskets that are infield on trailers. These are taken to the warehouse where they are moved off the trailers with a forklift and emptied into the dehusker. If he had any advice for other farmers, in the processing arena he would advise them to make as much use of gravity as possible. His reliance on a temperamental forklift is one he would like to see others avoid.

Once dehusked and sorted, the nuts are dried in bins, by diesel-powered burners for between 7 and 10 days.

TECHNOLOGY

Jaff is fairly old-school in that he sees the benefits and convenience of modern technology but insists that feet in the field, verifying the equipment, is vital, “Technology is all good and well but it needs to be checked up on. Starting your irrigation over the phone is wonderful but you need to be sure that you base that decision on more than just what technology is telling you eg: a probe in the sun may demand water even though the tree right next to it is perfectly moist.”

And with those wise words, we leave Jaff 8. Thank you, kind sir, for putting your reservations about “spotlights” and “radars” aside and being gracious enough to share what you know so that other farmers can learn and improve.

I am in Tzaneen and Levubu as I put the finishing touches to this story. Last week I was in Nelspruit, visiting the wonderful processors, nurseries and specialists that that area is home to … okay, I’ll name-drop just a bit … I spent time with Dr Theunis and Armand Smit, getting as much as I could on Moisture Management before they both leave our shores for Aussie. I also learnt more about the insect world from Dr Colleen Hepburn and Dr Schalk Schoeman and Dr Elsje Joubert. I even dropped in at the brand-spanking new world-class processing facility being set up by Global Macadamias. I am also interviewing the top farmers from the Levubu region and meeting further industry experts here. It’ll be two weeks in total that I spend on the road, collecting content that will form the backbone of many exciting articles in 2020. It’s going to be a very exciting year and I am privileged to invest it with you.

Until the next one, be safe.

D