On 9 June, I began a journey to Nelspruit, the heart of Mac-ville I’d been told. Not even half an hour from home and I was stationary … BIG MISTAKE to travel the N3 during an up-run of the Comrades Marathon! But, that was the last of my bad luck, thank goodness. And on Monday morning, bright and early, I was enjoying coffee with a local mac handling technical advisor who had introduced me to the farmers I was to meet this week.

We discussed the success that macs are enjoying here, the local climate and industry in general. I was intrigued to hear that there are even a few farmers exploring the crop between Oyster bay and Riversdale in the Cape. That made me wonder what climatic conditions macs are best suited to. Our technical expert enlightened me with the basics:

- No more than 4 to 5 days frost in a season.

- Soils should be a minimum of 800mm to 1m deep.

- Soils also need to be well-drained, ie: 800mm deep clay would not be great.

- Macs like humidity but blossom blight can become a problem if humidity is excessive.

- Low humidity causes the tree to shut down

- High temperatures with high humidity is tolerable but high temp with low humidity causes flower wilt, even if the ground is wet

- Water is essential for fertiliser absorption.

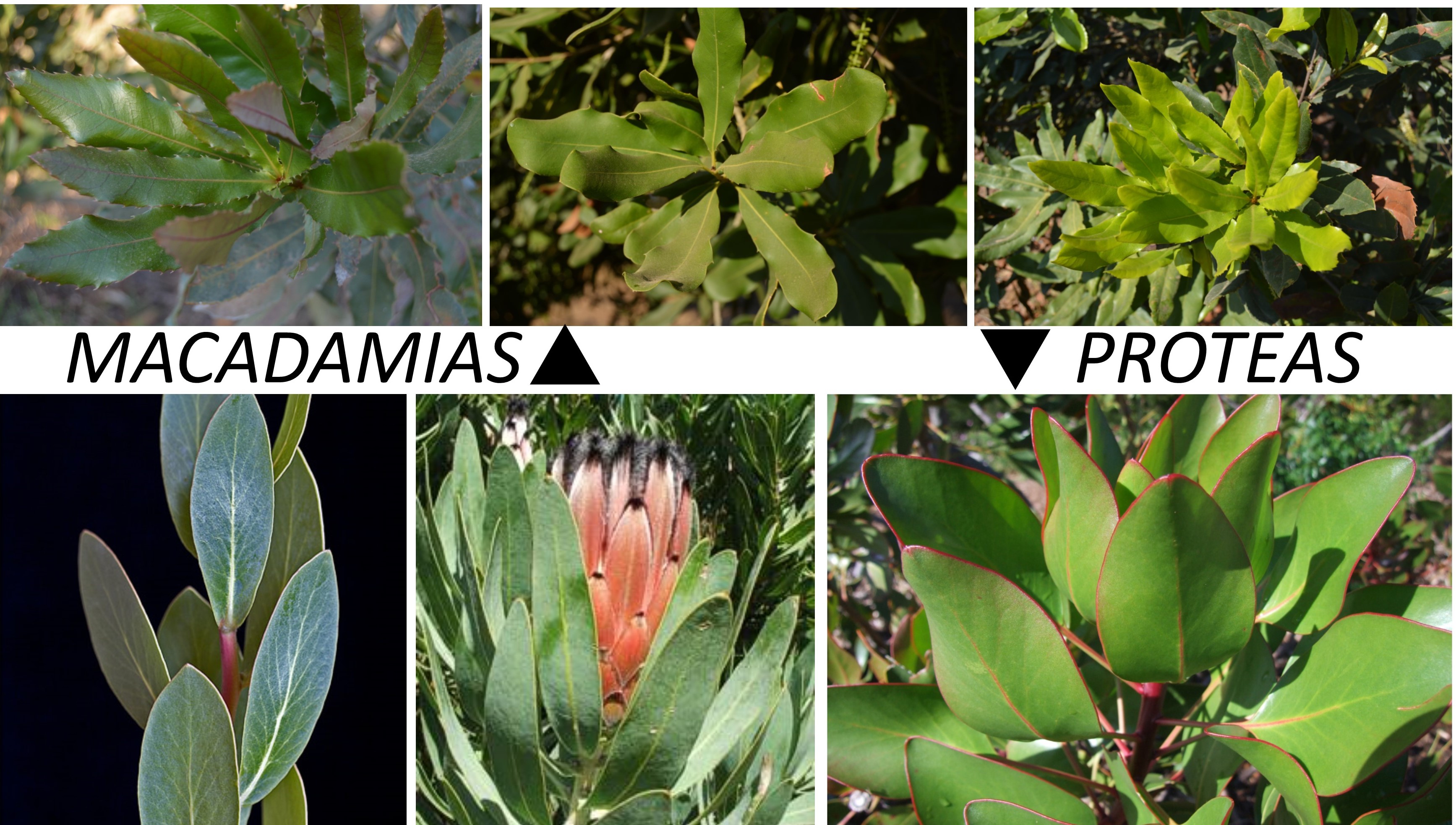

Once those basics have been met, macs face a good chance and I am excited to meet the Cape farmers next year and learn from their experiences. By the way (and I may be the last person on this face of this earth to learn this) macs are the same family as proteas, so them doing well in the Cape should not come as a surprise.

Now I see the family resemblance

Now I see the family resemblance

Besides the perfect climate in Nelspruit, another factor in the success of macs in this area is the farmers’ skills; many come from a background of farming export fruit which requires Global Gap accreditation. This requires extensive and superior farming practices to which the farmers have become accustomed over many years. Even though it has been a painful journey for them, they are now well-equipped for precision farming of the highest standards.

One thing that struck me as a stark contrast to the last time I was in this area, interviewing cane farmers in 2018, was how much increased security precautions had changed the landscape. Macadamias, being a high value crop, have not escaped the attention of our ever-perceptive criminals which has forced our farmers into another level of security:

The landscape in and around Nelspruit is changing in two ways: as macs enable a better living off less land, the farms are getting smaller and crop security is now a greater priority. The sign in the middle is not very clear – apologies, I literally took it ‘on the fly’ – but it warns of the CROP THEFT CHECKPOINT 100m! First time I had seen a road block specifically set up to combat crop theft.

The landscape in and around Nelspruit is changing in two ways: as macs enable a better living off less land, the farms are getting smaller and crop security is now a greater priority. The sign in the middle is not very clear – apologies, I literally took it ‘on the fly’ – but it warns of the CROP THEFT CHECKPOINT 100m! First time I had seen a road block specifically set up to combat crop theft.

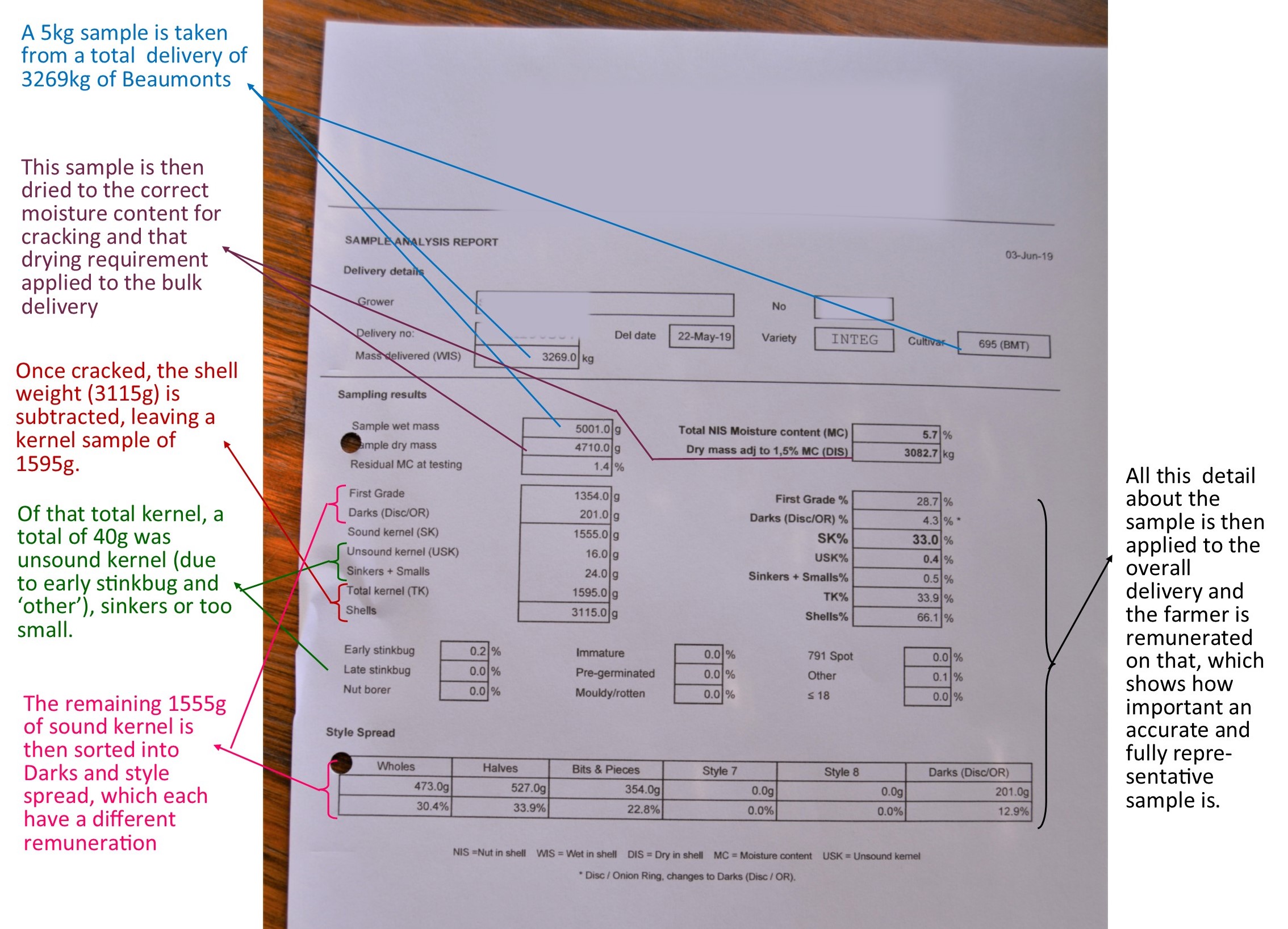

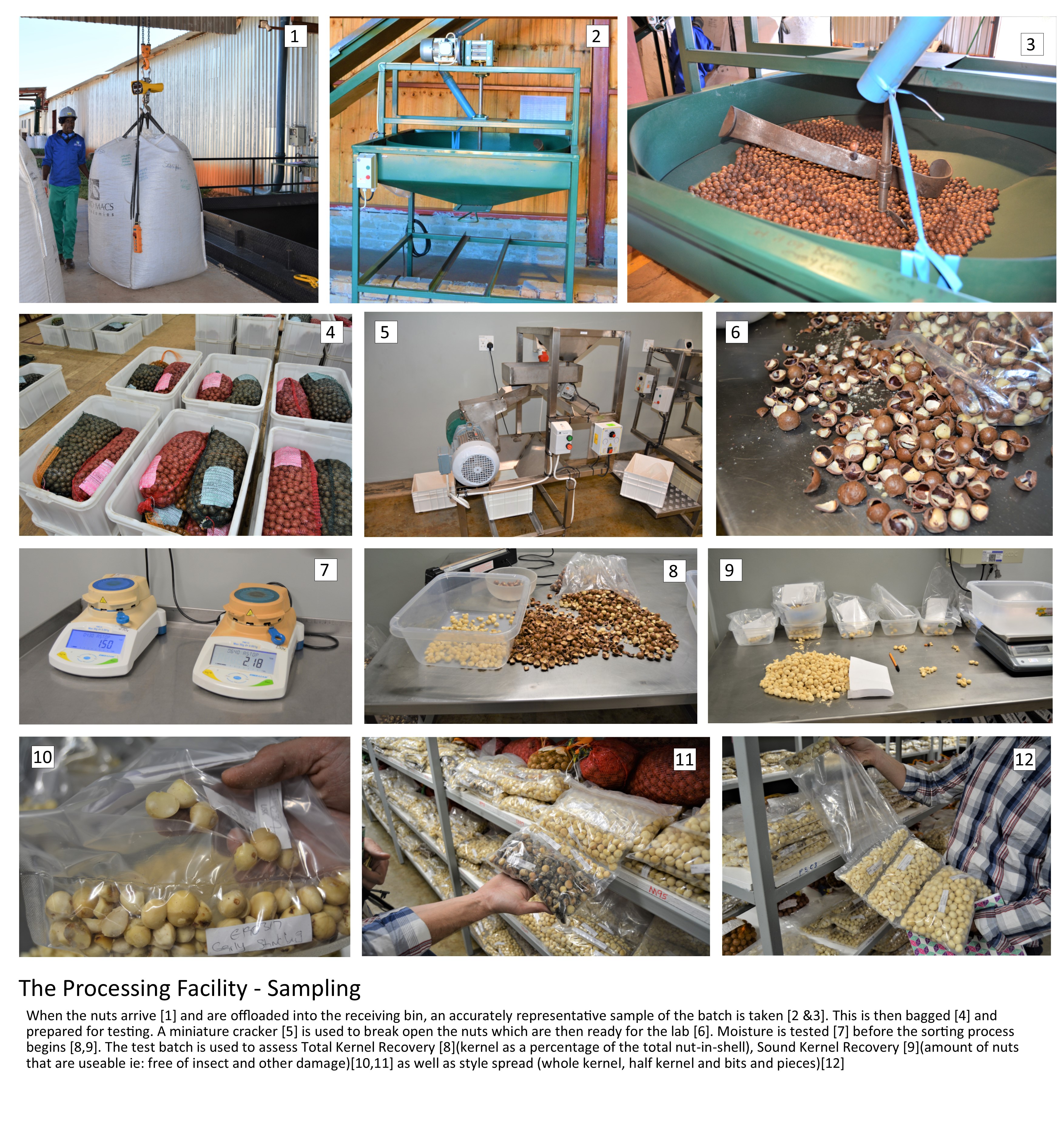

I was then very privileged to visit the processing facility. Seeing how the nuts are tested gave me insight into exactly what the farmers goals are ie: what makes good, quality produce?

- Moisture content of nuts received is important as it affects how much supplementary drying the processing plant must do.

- Quality is assessed in terms of three parameters:

- Crack out – % of the delivery that is kernel, as opposed to shell. This can be improved by reducing shell thickness. Thick shells can be the result of altitude and correlating environmental elements like temperature; colder weather = thicker shells = lower total kernel recovery. Some cultivars also just have thicker shells.

- Sound kernel – This relates mostly to insect damage which can obviously reduced by controlling the pests AND of course, sorting all the unsound kernels out before delivery.

- Style spread – This is whether your cracked out delivery yields wholes, halves or bits and pieces. Cultivar selection is the predominant factor in this eg: 816 tends to deliver majority wholes.

To illustrate these parameters, here are the outcomes of a farmer’s delivery:

Here are some visuals of my tour through the plant:

My kind tour guide also took me to a farmer who needed some pruning advice but I’ll save those details for a dedicated article on that topic specifically. I then went on to the first Nelspruit farm interview, with Jaff 2. Hope you’re all getting used to the acronym we now use for our successful farmers, in order to protect their privacy – Jaff stands for Just Another Fantastic Farmer.

My kind tour guide also took me to a farmer who needed some pruning advice but I’ll save those details for a dedicated article on that topic specifically. I then went on to the first Nelspruit farm interview, with Jaff 2. Hope you’re all getting used to the acronym we now use for our successful farmers, in order to protect their privacy – Jaff stands for Just Another Fantastic Farmer.

| Date | 10 June 2019 |

| Area | Nelspruit, Mpumalanga |

| Distance from coast | Approx 200kms kms, as crow flies |

| Soils | Sandy, very low (about 6%) clay |

| Rainfall | Average 700mm annually |

| Altitude | Av 600m |

| Temperature range | 7’C to 38’C |

| Varieties | Beaumont, Nelmak 2, A4, 816, |

| Hectares under mac | 40 hectares – ranging from 15 to 1 year old |

| Other crops | Citrus (lemons and oranges) |

Jaff 2 grows all the most popular Nelspruit cultivars; Beaumont, A4, 816 and Nelmak 2. He started way before the crop was popular and has even lived through a significant slump in the market. It is a privilege to discuss the industry with someone who has walked a very long road in it.

Jaff’s mac journey goes back 15 years, “when the price was a fraction of what it is today” laughs Jaff, “and then it fell a further 50%!” he grimaces. He cannot remember the reason behind the slump but he vividly remembers having a nursery full of young trees and no one to buy them. Obviously, Jaff has been in farming a long time and was well-established in citrus when he decided that diversification would be a wise strategy. Macs were the chosen alternative. The advice, back then, was to plant half your land to Beaumonts and the other half to a range of 3 to 4 other cultivars. Advice today is not so heavily weighted towards Beaumonts because of market demands for a bigger, creamier, whole nut which is more easily achieved with other varieties. The agricultural landscape is full of ups and downs – literally and figuratively – what is true for today isn’t going to be true in a few years’ time. Macs, being a long-term crop, make this volatility a challenge but farmers are accustomed to high risk with no guarantees. Sometimes it pays off, sometimes it takes perseverance through a tough spot and sometimes it’s best to move on. I am sure that’s why so many of the farmers I interact with are men and women of faith – without that, I don’t believe farming is possible.

Jaff advises that farmers carefully select their processor as that relationship is valuable – they can guide in terms of current and predicted trends. They also offer some security in terms of taking your produce. The organisation they have brought to the industry will help to stabilise it long-term. Jaff recalls when he entered the citrus industry many decades back. His first delivery resulted in him having to pay in! The Citrus Board had just been disbanded and suddenly everyone with a secretary and a fax machine became an export agent. The result was that neighbouring farmers were competing against each other and driving prices down. Once structure returned to the industry (a new citrus board) and minimum guarantees were put in place, the prices stabilised and improved. So, perhaps the organisation within the mac industry currently is partly responsible for the prosperity of the industry. That, and the fact that sustainable, protein-based, non-animal food sources are also très trendy right now.

Jaff does have plans to extend on the 40-odd hectares of macs he has currently by adding a few more each year. Right now, plans are being delayed by water challenges. Law stipulates that any virgin land turned to agriculture has to be passed through an approval process that involves an environmental impact assessment, taking water rights and capacity into consideration. Water through this area is sourced from the Kwena dam which is currently only 57% full and also feeds Nelspruit, White River, Malelane, Komatipoort – it even supplies parts of Mozambique! From last week the farmers have only been able to access 30% of their quota. Obviously, this situation places doubt on the success of any further applications for water access. Although many farmers prefer to bypass the red tape involved in applications, Jaff knows a few people, in the Barberton area, who have been fined up to R500 000 for flouting the law in this regard, so he will expand when given the official green light.

YIELD EXPECTATIONS

I may be wrong but I am sure that industry norm, across SA, for mac yield is in the region of 2,5 to 3 tonnes per hectare. Yet Jaff tells me that, in this area, average yield is closer to 5 tonnes per hectare. His best has been 6,9 tonnes which raised my eyebrows. Not as impressed by his own achievements, Jaff mentioned that his neighbour, whom I will also be interviewing this week, has reached 8 tonnes this last season!

Jaff is content with an overall average of 5 tonnes per hectare from his producing trees and to make his best TKR this season an average going forward – an impressive 45%, with an unsound score of just 1%.

Clearly Jaff has figured out how to farm macs well and I was eager to get into the nitty-gritty, kicking off with planning a new orchard …

SELECTING CULTIVARS & GETTING STARTED

As mentioned, current trends are favouring varieties like 814 and 816 which produce bigger nuts in line with current market demands. Although heed of market demands must be paid, it is still advisable to mix the basket with staples like Beaumonts which are far more reliable and hardy through adverse climatic conditions. A4 &, 816 are Jaff’s favourites – not for pruning or growing habits but for their quality nuts. The disadvantages are their tendency to be alternate bearing, the time they take to reach bearing age and the overall lower volumes produced.

When it comes to buying your young trees, Jaff warns that you should never try to ‘doctor’ a healthy tree right, even if it’s for free. In the long run, it’ll be more expensive than a pristine tree at a premium price. Some of the things to check are: bag size (needs to be big and deep), height of bud (needs to be about 30cm above soil level), height of tree (should be about a metre tall). Then there are invisible factors like the genetic history of the budwood; this needs to have come from a prolifically productive parent plant. You therefore need to deal with a nursery that has a reputation to protect and cannot afford to cut corners – your best reassurance that you are top quality across all spheres. Jaff used to graft his own trees but now he feels that there are experts who can do a better job than he can so he buys in the best plants he can when establishing a new orchard.

When Jaff first planted macs, he did it with only 4,5m between rows. He has since learnt that this was way too close and has had to remove every second row. The inter row space in this orchard is now 9m.

When Jaff first planted macs, he did it with only 4,5m between rows. He has since learnt that this was way too close and has had to remove every second row. The inter row space in this orchard is now 9m.

Most of Jaff’s orchards are 8m x 4m spacing. Lately, he has started ridging up when establishing a new orchard as the trees definitely grow quicker in highly loosened and aerated beds. In fact, one of his new orchards are struggling with the extensive vegetative growth of the young trees – they are catching the wind and breaking their spindly stems too easily. In preparation, Jaff cross-rips the land to ensure a good, even tilth. He then ridges, using a bulldozer rather than a grader, creating beds that are about 750mm high and 2m wide at the top.

Just like Jaff 1, Jaff 2 agrees that, when planning a new orchard, soil and water conservation attention trumps getting the best aspect so always prioritise the field gradient and water flow direction when deciding which way to pull your rows.

It is good practice to make sure soil samples have been taken so that you can disc in the right nutrients (eg: lime) before ridging. This becomes especially important if the area has been monocropped before as the soils are likely to be lacking in a few essential nutrients.

“The hole for the new plant must be a square,” advises Jaff, “some guys put in compost and bone meal at this stage but you have to be careful as the young trees burn very easily.” His policy is to give nothing for the first 3 months and then, when he does launch an elementary fertilising programme, he always ensures that nothing is ever placed close to the stem.

Continuing with this theme of caring for the vulnerable young plants, Jaff makes sure that the stems are covered. Temperatures can drop below freezing in parts of this province and when the sap flow up and down the stem is inhibited, the plant will die. To prevent this, Jaff supplies ‘jerseys’ in the form of thatching-type grass which is tied around the stems. This also protects against mechanical damage and sun-burn. (A bit like wrapping our kids in cotton wool 😊) An alternative to this is a white pipe which I saw used on other farms I drove past during my week in Nelspruit:

Jaff also sprays “Screen Dew” onto the young trees every 3 to 4 weeks until they are 3 years old. This was developed as a sunscreen (for trees) but has also proven useful in preventing frost damage during winter. This is hand-applied using knapsack sprayers.

While all this ‘babying’ may seem excessive, Jaff has learnt some expensive lessons that forced him into ‘mother hen’ mode; a few years back, he had just replanted a lemon orchard, alongside the N4 (in a dip), with macs. One night of unexpected black frost wiped the entire orchard out. Discouraged at the huge setback, he has since replanted that area with lemons but is tempted to try (more lucrative) macs again. If he does, this orchard will also get ‘blanketed’ through winter with a thin white membrane cloth. This involves wrapping each tree individually with the cloth for June, July and part of August. It allows for normal transpiration and enough sunlight penetration.

The overarching advice from this experienced farmer is that you TRY THINGS YOURSELF. “Base your trials on advice but then test the options in your own specific micro-climate.” He has learnt expensive lessons, in his citrus operation, by rolling out large scale investment based on advice. He now takes the advice and tests it on small plots (about 50 trees) before doing a large roll-out and, in so doing, saved himself a few costly experiences.

PRUNING

It’s great to have exposure to someone who has fully mature trees and therefore extensive pruning knowledge. Jaff warns that, at maturity, effective pruning becomes a vital part of maintaining high yields – all fruit trees like to be pruned. He prefers to limit tree height to 4,5 / 5m and ensure that sunlight and chemicals have access to the whole tree – you should always be able to ‘see through a tree’ to the next row and, at 12 noon, the shadow of the tree should be peppered with sunlight, like a leopard pattern, on the ground below.

This 816 has been pruned already but there is a need to come back and take care of the water shoots. They will take the small ones back to about 300mm because they will produce fruit set again for next year. The bigger ones will be taken out completely.

This 816 has been pruned already but there is a need to come back and take care of the water shoots. They will take the small ones back to about 300mm because they will produce fruit set again for next year. The bigger ones will be taken out completely.

Jaff has chosen to use a sub-contractor to prune. He admits this is not ideal but it is essential in his operation. As soon as the macs have finished being harvested and are ready for pruning, his oranges are ready for harvest. Rather than becoming weighed down with a large permanent work-force, he has opted to sub-contract a few of the activities and, for now, mac pruning is one of them. This also enables him to get the macs pruned as soon after harvest as possible ie: as soon as a tree is stripped of all its produce, it is ready to be pruned. It makes sense that this sets the tree up for maximum harvest potential the following year. The risk, with using subbies, is that the pruners may not be well trained or experienced but Jaff says it just takes some supervision and can be managed. Having said that, Jaff also advises that you may just want to leave the farm when your trees are being pruned because it is quite traumatic to see all the (nut bearing) branches being cut away. But, if leaving is not an option, then he suggests taking the process one branch at a time: cut a branch, step back and see how the tree has changed with the branch gone, then go back to cut the next one.

Jaff shakes his head and says, of these A4s, “It’s a silly tree, you never know how to prune it.”

Jaff shakes his head and says, of these A4s, “It’s a silly tree, you never know how to prune it.”

IRRIGATION

All Jaff’s macs are irrigated using microjets. He monitors moisture levels with probes but uses a large dose of common sense and experience in deciding what to do with the data provided by this technology. For example, at this time of the year, he knows the probes will be advising more water, but he purposely withholds it. Water, at this stage (straight after harvest), will permit the trees to initiate flowering. This would take away from the flowering in Spring – the one Jaff would like to turn into the crop. Stress, caused by lack of water now, helps to delay the flowering and produce a GOOD flowering at the RIGHT time. Natural manipulation to achieve the purposes of agriculture. The same practice is followed in the citrus orchards and Jaff therefore has it down to a fine art. Whereas orange trees show stress through wilting, macs don’t so it is a bit more tricky but Jaff has established that one good watering after harvest (and then no more water) is what works best in ‘training’ the trees to flower timeously. Despite his best efforts, some flowering will still happen but most will not set, except the Nelmak 2s which will result in earlier harvests of a poorer quality but Jaff knows to expect that his first few deliveries of the season are going to be underwhelming.

Early season Nelmak 2 flowers

Early season Nelmak 2 flowers

The scarcity of water is a concern but Jaff says the industry is prone to over-irrigating. Broadly speaking, macs will thrive on less. When water levels are low, he changes the heads on the microjets to shorten the distance sprayed; this conserves water.

Another practice that would reduce water requirements is mulching; although a nice clean floor is visually pleasing, it is detrimental to the end goal of water conservation and the stimulation of healthy microbial life around the surface roots.

Whilst on the topic of optimal water use, we discussed the option of drip irrigation and Jaff had some interesting input:

- Microjets, being above surface, are easier to manage in terms of detecting blockages and faults.

- Microjets act as air conditioners which is priceless to preserve flowers and increase fruit set, especially when those hot days happen at critical stages. Walking into the orchards on a blistering day, when the jets are on, is a pleasure and Jaff firmly believes it makes a substantial difference to his results.

- Water conservation during lean times can be achieved by changing the heads on the microjets.

- Drip irrigation is purported to save 20% in water usage and work better in clay soils, which is always a consideration not to be overlooked.

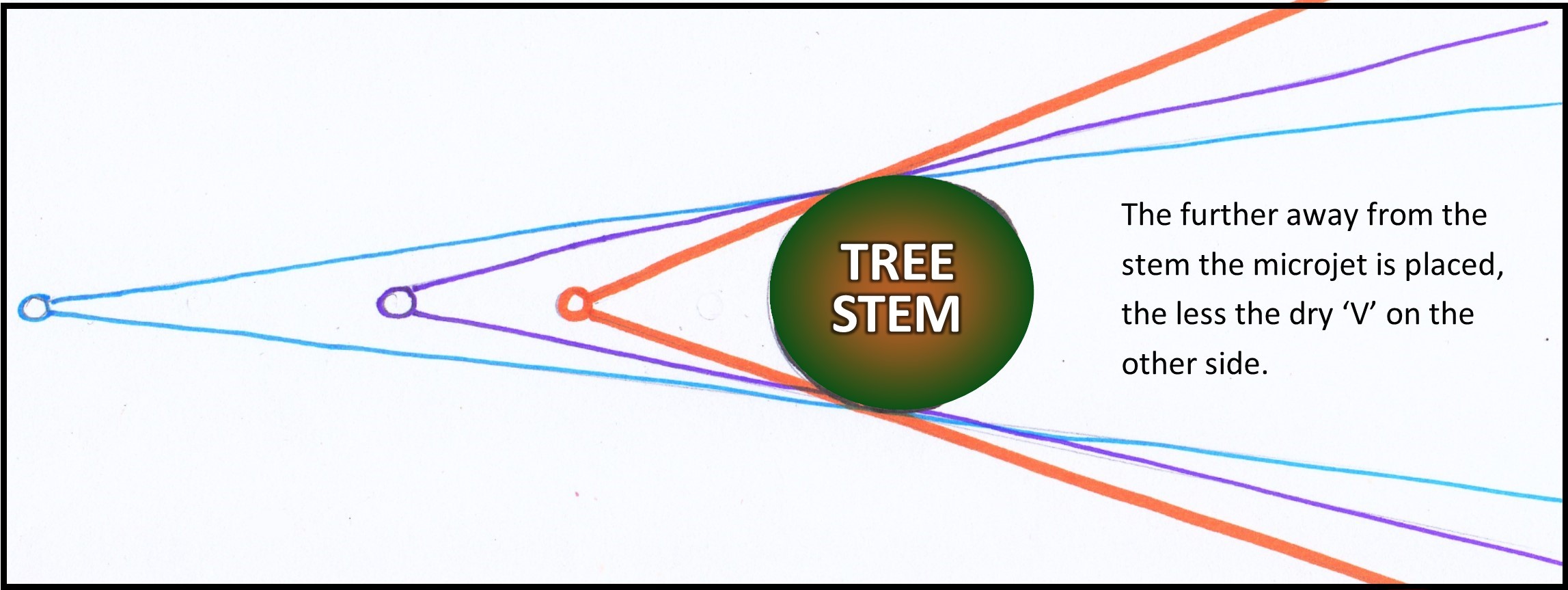

- When using microjets, always make sure that the head is at least 400mm away from the stem of the tree to avoid damage and the size of the dry V on the other side of the tree.

- Whatever system is used, is must be professionally designed from the outset. Water is too precious a commodity to waste through poor system design or layout.

FERTILISING & MULCHING

Mulching has become an essential part of Jaff’s success recipe – he composts the mac husks, adds kraal manure, wheat straw, grass cuttings and anything he can put through the chipper and mulcher. He also supplements with lime and nitrogen (which accelerates the breakdown of organic matter). Add a splash of water and turn it a few times through winter and you have a great mulch to place around the trees. It also helps with weed control. To make things easier for the pickers, Jaff moves the mulch away during harvest, and back again afterwards; this is only really feasible on a small farm – the age old rivalry between quality and quantity.

An area of marked difference between farming cane and macs is in the fertilising; I cannot think of an instance where cane was ever killed with kindness but it appears that this is a reality in the world of macs. Jaff warns of two instances wherein it is best to show restrain:

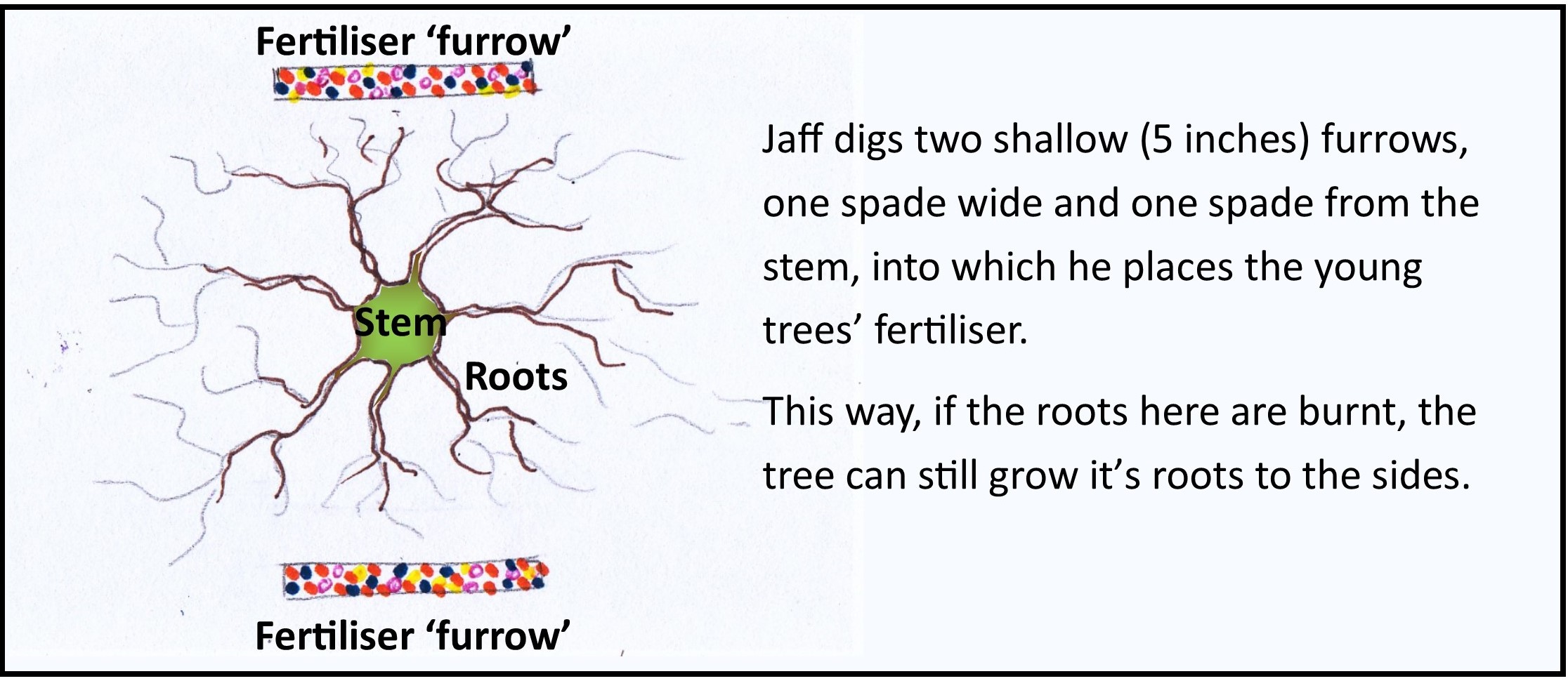

- Young mac trees are easily burnt with fertiliser so he holds off for the first 3 months and then uses a slow release, micro-combi product, making sure the fertiliser is not applied right the way around the tree:

This general fertiliser has a broad range of elements and lasts up to 6 months although Jaff only applies it annually, in August / September for the first 3 years of the tree’s life. In addition to this, a foliar feed is sprayed on ‘every now and then’.

- Another illustration of why restraint is required when fertilising young trees is demonstrated by one of Jaff’s 3-year-old orchards. The vegetative growth has been so prolific here that the wind is proving too strong for the young tree’s spindly stems and many trees have simply broken off. The orchard is also flowering very poorly. It’s now a matter of withholding fertiliser until the stems strengthen enough to sustain the leafy canopy in windy conditions.

After so many years of farming, even Jaff is still learning and testing. One of his latest trials involves soils and leaf sampling twice a year; Oct / Nov and again in March / April. The difference between these to sets of results will tell Jaff what the trees used in that season and therefore, what to supplement. Once-off sampling tells you what is lacking in the soil / plant but having two readings adds further information in terms of what and how much of each element was used.

There were three more ‘pearls’ Jaff dropped on this topic that you may find as interesting as I did:

- Foliar feeds are important but you are wasting time, money and resources if you apply them any other time than when the tree is in flush ie: new growth is fresh and clearly evident. Older leaves simply don’t take in anything.

- An industry that is doing well will attract profiteers. If there are no more ‘pieces of the pie’, shrewd business people will create ‘needs’ through clever marketing. Before you know it you’ll be buying complex concoctions to treat low risks. Jaff handles this in two ways:

- By staying astute and KEEPING IT SIMPLE. Do your homework and verify all information fed to you.

- Acknowledge that there is so much you don’t know – that’s why there are people with doctorates in these fields. Just be careful of whom you take advice from.

In an effort to simplify, Jaff is now only feeding his macs ‘straights’, through foliar feeds and granular fertilisers, and following the advice of independent advisers (ie: not corporate reps).

PEST & DISEASE CONTROL

Jaff’s biggest headaches have been stink bugs and thrips but, this year, nut borer also showed up for the first time. Jaff says spraying alone is not enough, it has to be EFFECTIVE spraying to keep your orchards pest-free. Some of his pointers in this regard are:

- Proximity of different crops: Having another crop, with a different spray programme, alongside the macs, as has happened with Jaff’s citrus, has been a challenge. Now, instead of dying, the thrips are simply moving over to the oranges when he sprays the macs and to the macs when he sprays the oranges. “You cannot just keep spraying,” sighs Jaff, “as that will impact resistance.” He advises other farmers to pay attention to the proximity between various crops when planning new orchards.

- Staying in touch with a broader community: rather than everyone scouting continuously, Jaff has a WhatsApp group with others in his valley. They keep each other informed of what is active and co-ordinate sprays. The processors’ technical advisors are also very good at keeping the farmers they serve informed about what they are seeing in the area. This also facilitates a synchronised and targeted plan.

- Change it up: make sure you don’t use an active ingredient exclusively as the insects will build resistance, rendering that weapon impotent.

- Seasonal vigilance: you know when conditions are right for certain challenges so make sure you’re ready ‘in season’ eg: warm and wet = fungicide susceptibility. Make sure that predisposed orchards (Beaumonts often struggle with Blossom Blight, especially when growth gets too dense) are well-pruned with adequate sunlight and airflow.

Although Phytophetra is common and carried in the water, careful orchard development can eliminate a lot of it; Jaff has a particular orchard that struggles constantly and it is because, during the establishment of this orchard, Jaff didn’t have the resources to address the large rock layer not far below the surface. Now the drainage there is poor and the trees are struggling.

Jaff paints white PVA on all the large tree stems. This is a common practice in this area and is meant to protect the trees against lawnmower (airborne rocks) and critter (like porcupine) damage.

HARVESTING & PROCESSING

Jaff uses ethapon on Beaumonts and Nelmak 2s but not on the 816s or A4s, although he admits that it is a challenge to get the nuts off the 816s as they are big trees. Because of this he has used ethapon, at half dose, on this cultivar before, very successfully. Given the finicky nature of these trees he is reluctant to advise this to others though.

15-year-old 816s

15-year-old 816s

Next up is the dehusker; here, A4s prove challenging as they have a gluey substance between the husk and shell. This can block up the dehusker and adhere the nuts to the elevator. This year, he left the nuts in the orchards, on the ground, for a few days after stripping. It helped, so next year he will add a few more days to this natural drying time.

Once off and through the dehusker, the nuts need to be sorted and Jaff places great emphasis on having a white sorting table mat with excellent overhead lighting, “these are inexpensive items that can make a massive difference to your unsound kernel count.”

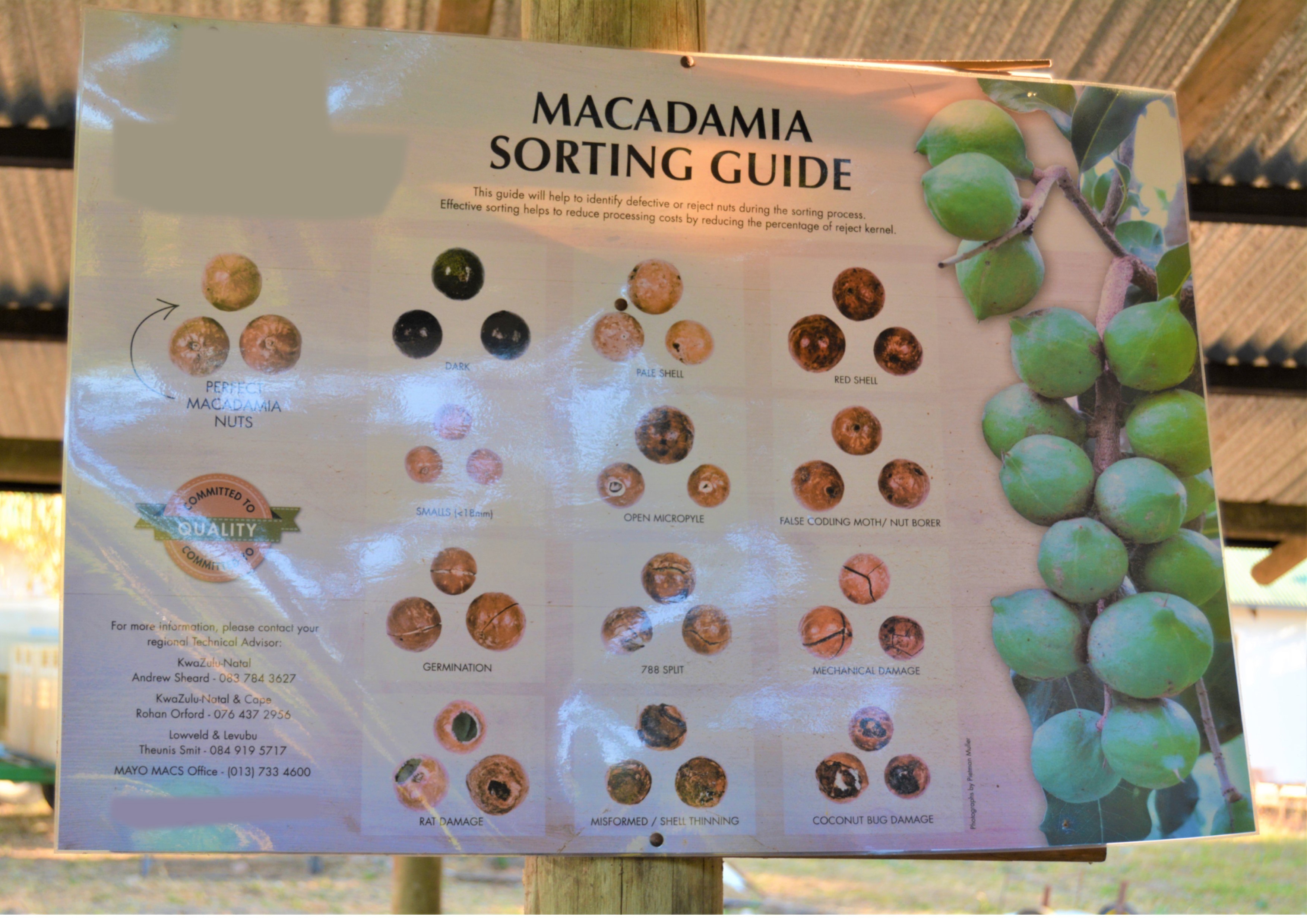

On the table, Jaff is after borer holes, darks (black), immature (burst open), mechanical damage (broken by dehusker), mould and undersized nuts, as per the poster below:

From here the sorted nuts go into drying bins. Jaff explains that he could have another step before then, in the form of a bath, to remove all ‘out of season’ nuts but he prefers not to do that unless it is early season Nelmak 2s. It’s a trade-off of risks: will there be sufficient ‘floaters’ to warrant the risk of nuts becoming too wet. If he does use the bath, he makes sure the nuts go through a pre-bin drier.

While on the point of drying, Jaff recommends that drying bins be designed by someone well-qualified. Fans, shape, capacity etc are all facets that may seem simple but small miscalculations can render the process ineffective.

Currently Jaff is using ambient air but is about to install ducting that will direct the warm air from the roof down into the system. He is cautious about using elements (like electrically-heated ones) as he has known a few facilities that have burnt their bins and would prefer not to involve this stress.

We can all be grateful that Jaff is willing to share his mistakes so that we can all benefit from the lessons – he has learned (the hard way) that when it is raining, and you are using ambient air to dry your produce, you should turn your fans off. Not doing so means that you force the damp air into the bins where it creates mould.

In this facility, the nuts take an average of 12 days to dry and are then sorted again before being delivered to the processor.

And that rounds out the experience of mac farming with Jaff 2. Although he thought he didn’t have a lot of wisdom to impart I am sure he’ll see how wrong he was, when he reads this story. Thank you for your vulnerability in sharing all your successes and failures and for opening your doors to TropicalBytes and all the avid readers.