| Date interviewed | 3 April 2019 |

| Date newsletter posted | 23 May 2019 |

| Farmer | Marlen Pillay |

| Farm name | Wellvale Farm |

| Mill | Darnall |

| Distance to the mill | 31 kms |

| Area under cane | 40 hectares |

| Annual quota | 1100 tonnes per year |

| Cutting cycle | 16 to 18 months |

| Av Yield | 50 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 13% RV |

| Varieties | N55, N59, N27, N41, N31, N39 |

| Soil type | Predominantly very sandy |

| Rainfall | 750mm annually |

| Diversification | A range of Indian vegetables & herbs, pineapples, custard apples. |

Every year I ask every mill group area to provide a list of their top farmers. Some oblige, and some don’t. This year, Darnall decided to step up and introduce us to their award-winning small-scale grower; Marlen Pillay. Marlen recently won the Environmental Award, presented to him after the local Environmental Committee assessed his farming practices in terms of waterways, contours, soil conservation, crop rotation and other activities that can have an impact on the greater ecosystem.

Marlen, holding his Environmental Trophy alongside the highly-prized and coveted SugarBytes ‘thank you token’.

Marlen, holding his Environmental Trophy alongside the highly-prized and coveted SugarBytes ‘thank you token’.

Marlen’s farm lies in the Kearsney valley so he’s actually closer to the Gledhow mill but, with transport incentives, he supplies the Darnall mill, which is 31kms away.

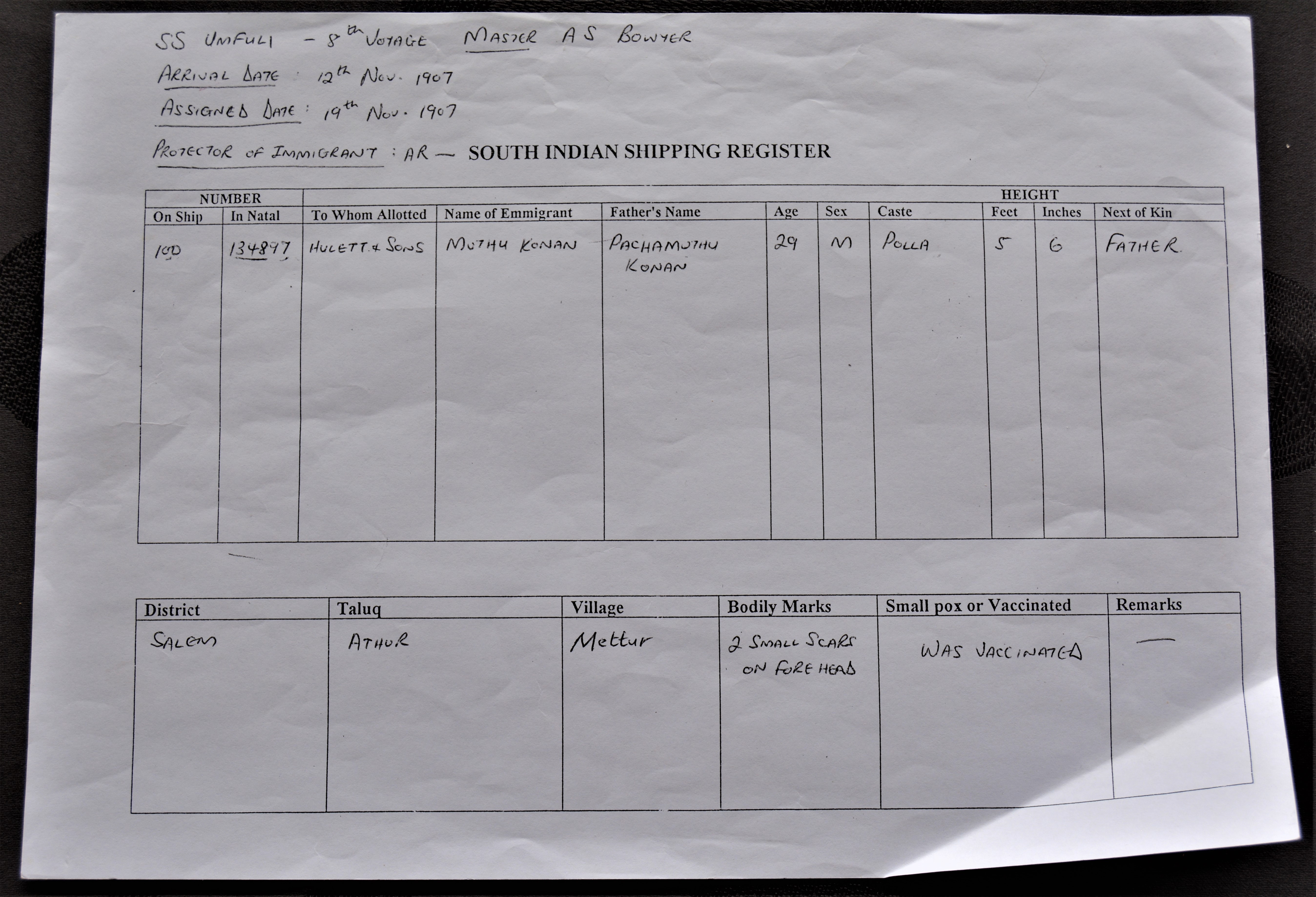

Marlen has a very rich heritage which he can trace back many generations. We’ll begin with his grandfather who was an indentured labourer. Muthu Konar arrived in Durban, on the SS Umfuli, on 12th November 1907. A week later he was assigned to Hulett & Sons and went to work at Mount Edgecombe as ‘coolie’ labour. I learnt that this is not as bad a word as I’d always been led to believe and simply refers to someone who works, physically, for a wage. I was also relieved to learn that indentured labour was not a form of slavery but, instead, it was a voluntary system wherein people could get employment in one of Britain’s colonies around the world. Although Muthu did come to South Africa with the impression that he would be working on the gold mines, he still had gainful employment when he arrived here. After a while at Mt Edgecombe, he relocated to Tinley Manor and then on to Hulett-owned tea plantations in Kearsney where he saw out his term of indenture.

Muthu Konar’s original ‘travel manifesto’.

Muthu Konar’s original ‘travel manifesto’.

I have always found the indentured labour system fascinating, in a sceptical kind of way so, if any of you share my intrigue, here is a touch more background: a total of 384 ship-loads arrived from India between 1860 to 1911. They came from Madras and Calcutta, each carrying 300 to 700 migrants per ship. Women and children were among the travellers; overall, 152 184 people made the journey to South Africa. There was a concerted effort to ensure a decent quota of women and they set that requirement at 25 – 40 women per 100 men. South Africa wasn’t the only country to recruit indentured Indian labour, the practice was common throughout the British empire. Initially it was designed to fulfil the demands of agricultural work, but later expanded into railway line building, coal mining and then the sugar estates began earnest recruitment. India has always been a successful cane growing nation and is probably why so many of their nationals made such a profound impact on the industry, here in South Africa.

Mr Konar bought the 8-hectare plot, that I had the privilege of visiting today, in 1940. After 5 or 10 years, he would have had the option of free passage back to India but, like many of his peers, he chose instead to make South Africa his home and continue to make a weighty contribution to our rich and colourful heritage. Marlen explains that Indian people have an expert ability to live off very small pieces of land with virtually nothing and that explains how his grandfather managed to grow his little family to 12 off the tiny plot.

Left: Marlen’s grandparents; Muthu Konar and Kanniamma Konar (nee Pillay)

Left: Marlen’s grandparents; Muthu Konar and Kanniamma Konar (nee Pillay)

Right: Site of the original wood and iron home is marked by this mango tree. Marlen plans to rebuild a replica.

Marlen’s dad, Parthasarathy Pillay, was the 9th blessing born to his brave parents. He ended up being a Pillay due to the inefficient birth registration procedures of the day. His mother’s employer registered all the Konar children but, as she only knew her employee as Kanniamma Pillay, all the children were registered with the same surname. Some of the family has since corrected the error but Marlen’s line continued on as Pillays.

Mr Pillay’s dad died when he was only 6 years old but the senior siblings kept the family together and the farm running. They cut, loaded and transported cane to the mill themselves, supplementing their income with veggies. In 1954 they began a concerted effort to increase the size of the business by buying up available neighbouring farms and successfully grew to 200 hectares. When it came time for the 10 siblings to start their own careers and families, most of the farm was sold off to compensate them for their investments. Mr Pillay chose to stay and continue farming.

Although Marlen has 2 older sisters, they are both married and pursuing careers of their own. He has always had a deep connection to the land and chose to make this his future. His mom explains that, from a little boy, he would spend all his time in the fields or next to her at the morning markets. In high school, he wouldn’t even pause to remove his school tie before running off to check on his animals when he got home.

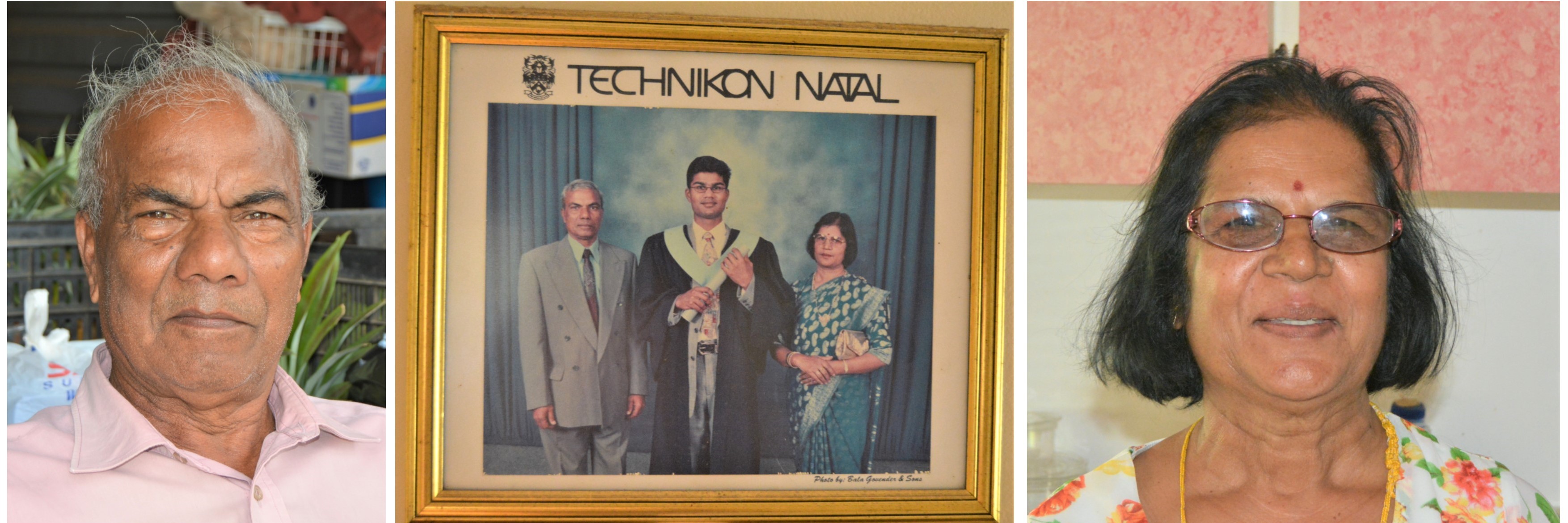

Marlen studied horticulture at Tech Natal and has a landscaping business in Ballito as a result of the practical year he spent completing this diploma.

Left: Mr Pillay, who lavished me with produce when I left – pineapple, custard apple, granadillas … Centre: Marlen graduating, Right: Mrs Pillay, who treated me to the most wonderful hospitality, complete with coffee, sandwiches, and a special lunch. An especially warm and welcoming family indeed.

Left: Mr Pillay, who lavished me with produce when I left – pineapple, custard apple, granadillas … Centre: Marlen graduating, Right: Mrs Pillay, who treated me to the most wonderful hospitality, complete with coffee, sandwiches, and a special lunch. An especially warm and welcoming family indeed.

The landscaping business consumed most of Marlen’s time until his dad had a massive heart attack in 2004 and needed a triple heart bypass. That incident drew him back to the farm where he could be close to assist his dad. But, in 2009, there was another set-back when they learnt that the whole farm was under claim. This revelation plunged Dad into a serious depression and forced Marlen to take the farmer’s seat completely. Nine years and much money later, the issue was resolved when the claim was declared unfounded. Not only has Mr Pillay managed to shake the depression but Marlen is now full of renewed vigour to grow their operation. His passion for this area and its people is clear and helped me understand why his dad reacted so when faced with the prospect of being displaced. The area is even named after Mr Konar, whose Zulu nickname was Kwamehlo Mnyama. This means ‘black eyes’ and is now the locals’ name for this valley.

Marlen believes the area is one of the safest in the country. There is no crime to speak of and the Pillays have an excellent relationship with all their staff, some of whom have been with the family for 45 years. Marlen is affectionately known as Mali (money) in the area.

Marlen’s daughters love getting involved in the land, working alongside Dad and Grandpa.

Marlen’s daughters love getting involved in the land, working alongside Dad and Grandpa.

LARGE SCALE VEGGIE FARMER

Unlike most SugarBytes stories to this point, sugar is not the star of this story. Marlen is a large-scale veggie farmer who plans to expand his cane crop as he picks up neighbouring farms. Veg farming is a completely different ball game and I confess to being ill-equipped to understanding the finer details and strategically directing the interview. We therefore went on a winding meander through the intricacies of farming veg and cane alongside each other.

‘Veggies’ have a far shorter growing cycle, are replanted every season and there are MANY options to chose from. This makes it a more dynamic and fluid environment with regular trials and replacements as the market, weather and seasons fluctuate.

Right now, Marlen is farming mostly Indian veg and herbs; calabash, runner beans, curry leaves, brinjals. He’s also expanding into wonderfully delicious pineapples and custard apples.

The Umvoti river runs around the farm and provides the water required to irrigate the veg.

The last few years have brought extreme weather conditions to this valley. Heavy downpours have caused huge wash-aways as can be seen in this field above. The unusually hot conditions we had in January this year delayed planting of his main crop; runner beans, and, no sooner had Marlen bedded these seedlings down in February, when the rains washed them away in March.

The last few years have brought extreme weather conditions to this valley. Heavy downpours have caused huge wash-aways as can be seen in this field above. The unusually hot conditions we had in January this year delayed planting of his main crop; runner beans, and, no sooner had Marlen bedded these seedlings down in February, when the rains washed them away in March.

Usually Marlen provides 50 to 60 tonnes of runner beans per season into the national market but this year he may not fulfil that demand.

Top left: Rose Geranium, bottom left: curry leaves. Right: Custard apples.

Top left: Rose Geranium, bottom left: curry leaves. Right: Custard apples.

CANE FARMING

While the veg that Marlen grows is comfortable in the sandy soils that constitute the majority of this farm, the cane tends to turn its nose up at it. Even so, Marlen says that sugar is still much easier to farm.

Before we even get into the details, Marlen points out that farming cane here is very different to what SugarBytes has presented thus far; not only because it is being done on a small scale but in the harshest conditions as well. The yield, just 50 tonnes per hectare, is considerable given the challenges to get there. Currently producing about 1100 tonnes annually, with an average of 13% RV, Marlen plans to expand to 3 to 4000 tonnes, which will still be manageable in his hands-on structure.

He is supported by 15 permanent staff members and employs casuals when necessary. Students gratefully snap up the opportunity during their school holidays and he had 26 helping to plant sugar cane this past December.

All weeding, fertilising, spraying is done by hand and Marlen controls the cool, early morning burns himself. Harvesting and haulage is contracted out.

Planting: Crop rotation forms a large part of the programme on this farm. After an average of 10 ratoons, with a 16 to 18 month growing cycle, a field is given a break from cane for about 3 to 4 years. During this time the field is used to grow veg, focusing on nitrogen fixing beans in the run-up to a new sugar planting. Lime is always added to every field before planting. Marlen plants cane throughout the year – yes, right through winter! That’s a first for me. He insists on double-stick, with his own seedcane, and gets almost 100% germination, even when a light frost has dusted the fields.

Inter-row spaces of at least one metre.

Inter-row spaces of at least one metre.

The sandy soils mean that he can still get a decent furrow without having to till the fields excessively. Some of the heavier soils need to be ploughed and harrowed but they are the minority. Marlen allows a very spacious gap (1 to 1,2m) between rows so that he can intercrop with vegetables. This is done for the first 3 to 4 ratoons but after this the soil gets a bit hard and requires ripping before another veg crop can be cultivated.

N59, 2 months old, on some of the farm’s weakest soils.

N59, 2 months old, on some of the farm’s weakest soils.

Filter press (about a half a spade-full per set) is added to supplement the organic content of the soil. Marlen sprays the sets with a chemical that helps to prevent rotting, especially in the wetter fields. Bandit is also sprayed to prevent thrips and then the furrow is closed. After that, no tractors access these fields as all activities (except for land prep and haulage from the field) are done by hand.

Varieties: When Marlen went to India on a research mission recently he discovered that the variety he had grown up with – NCO376, also known as ‘poor mans’ cane’, originated in Coimbatore (a South Indian state). As we know, that variety is no longer permitted and Marlen is looking to N27, N55 and N41 to bring him success. N39’s drought intolerance has been disappointing and is being phased out. N31 is great in the sand, survived the drought well and seems to have some stamina too.

Marlen’s favourite variety; N27. It has given him 13% RV at 8 months.

Marlen’s favourite variety; N27. It has given him 13% RV at 8 months.

These fields, both planted in October – 5 months ago, N55 (right) & N41 (left), are also looking very promising.

These fields, both planted in October – 5 months ago, N55 (right) & N41 (left), are also looking very promising.

N31 on the left, N39 on the right.

N31 on the left, N39 on the right.

Pests and diseases: We all know that sandy soils are a playground for nematodes and it’s no different here. As the recommended chemicals are very expensive, Marlen applies them when he is able to which is normally every alternate year. He has heard that Khakibos is a natural remedy and plans to purposefully germinate the weed in a resting field and then plough it in before planting new cane to test the theory.

Living side by side with vegetables is beneficial for the cane: they get a lot of foliar feeding (every 3 weeks) when mist blowers fertilise the veggies. An insecticide is added to this mixture and most certainly discourages the cane pests as well. The veggies are also doused with Bandit once the first two leaves have appeared and this will be a further discouragement for any thrips eyeing the cane.

A larger ‘pest’ that we don’t usually have too much trouble with is a beautiful, four-legged species …

Unfortunately, there are no sprays and Marlen is having to have a few stern conversations with his neighbours. The devastation they have been causing lately is substantial.

Fertilising: Soil samples are regularly sent to SASRI and the fertiliser recommendations followed. Usually that means that granular 2:3:4 is placed in the furrow when plaanting but, on occasion, MAP is called for. The first top dress of LAN is applied when the cane spikes and is followed by 1:0:1 after a couple of months. Depending on the weather, a further 1:0:1 application may take place before canopy. From the 3rd ratoon onwards, 5:1:5 (in split doses) is used to supplement the cane.

Weed management: The practice of intercropping (especially when it is with calabash) helps to suppress the weeds in the cane fields. Any persistent weeds are dealt with by hand where possible.

He says that Gooseberries and Morning Glory are two of his biggest headaches. He was amazed when I told him that I have been known to pay a small fortune for gooseberries from Woolworths!

On the new farm that he bought recently, there’s a new weed that he is really struggling with. He’s not sure what it is and it hasn’t succumbed to Metribucin, Falcon Gold or Gramoxone yet. You can see how the cane is battling with the waging war, while the weed thrives.

On the new farm that he bought recently, there’s a new weed that he is really struggling with. He’s not sure what it is and it hasn’t succumbed to Metribucin, Falcon Gold or Gramoxone yet. You can see how the cane is battling with the waging war, while the weed thrives.

Ripeners: Marlen uses chemical ripeners across all the cane on his farm, unless the frost has visited and done the job naturally. He has conducted trials to assess the returns he gets from investing in this unsubsidised expense and has concluded that the RV% is increased by about 4 when he applies ripener. Certainly worth-while. The chemicals are sprayed on to 4 rows at a time, from knapsacks. The wider inter-rows are helpful when the knapsack operators have to access the fields.

LEARNINGS FROM INDIA

As mentioned, Marlen recently journeyed back to the land of his heritage in search of what makes his people great cane farmers. What he discovered is that this might be a developing country but, in terms of sugar cane farming, they are far more advanced and he found many opportunities from which to learn.

All growers in India are small-scale, family-run units, which made the learnings more relevant to his situation here at home. Something that isn’t similar is that there, the farmer is paid for everything he delivers to the mill: fibre (used to generate electricity), sugar, and alcohol.

They also practice intense, companion-planting intercropping with veg; eg: using onions to control aphids and nematodes.

Burning cane is illegal in India so all cane is trashed. Marlen would like to trash exclusively but the natural bush surrounding the farm means that there is a high concentration of wildlife throughout his farm; he fears that, without running a cool fire through the field before harvesting, his people will be at risk of the ‘teeth’ that lurk within.

The water table is also very shallow and he saw boreholes being HAND-dug. Overall, the trip helped him to appreciate what he has here at home and the fact that he is actually well on the way to becoming a medium-scale farmer. He also imported some Moringa seeds and is profitably farming the tree now, marketing the seed, also known as the ‘drumstick’.

Marlen shows me the Moringa seeds, sold as “drumsticks” in the Indian markets.

Marlen shows me the Moringa seeds, sold as “drumsticks” in the Indian markets.

FUTURE

Sadly, many youngsters from this valley have left the farms in pursuit of urban-based livelihoods. As a result, there are many abandoned properties. The conditions here are tough (the area is actually known as ‘the monkey lands’) and he holds no judgement of those who have chosen an easier path, in fact, he sees the opportunity presented by the situation; he’s prepared to tackle whatever this beloved land of his throws at him and wants to buy as much of the remaining land in this valley as he can. Currently, he owns about 120 hectares and is looking to pull the remainder of the +/- 350 hectares into the fold.

One of the abandoned homes is almost hidden in the cane field.

One of the abandoned homes is almost hidden in the cane field.

Marlen explains that this valley is a wonderful ‘mist bowl’ and provides generous amounts of precipitation, especially on winter mornings. Strong berg winds also visit but they bring rain as compensation for the unbearable heat units. Then there are the south-easterly winds that also bring rain. The way he talks, you can see that this is his Eden.

Marlen is proud to say that he has always managed to always pay wages and bonuses, regardless of how much personal sacrifice has been required. He doesn’t believe that self-enrichment is the most important goal. He’s grateful to have been able to live his passion and pay his bills and looks forward to finding a way to one day allowing his fellow soil-toilers to take over the reins to his piece of paradise.

Thank you Marlen for showing me true Indian hospitality and welcoming SugarBytes into your home and business, we all look forward to seeing you grow into the successful medium-scale farmer you plan to be.

Thank you Marlen for showing me true Indian hospitality and welcoming SugarBytes into your home and business, we all look forward to seeing you grow into the successful medium-scale farmer you plan to be.