| Date interviewed | 15 March 2019 |

| Date newsletter posted | 6 May 2019 |

| Enterprise | Donovale Farming Company |

| Mill | Noodsberg |

| Distance to the mill | Av 50 kms |

| Area under cane | 860 hectares (90h under drip irrigation) |

| Annual tonnes | 42 000 tonnes (last year), would like to be closer to 48 000 tonnes next year |

| Cutting cycle | Ave 22 months |

| Av Yield | Approx 93 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 12.4% |

| Av rainfall | 750 – 780mm |

| Varieties | N12 (68% of the total), N36 (11% of the total), N47, N51, N54, N61, N62 |

| Soil type | Mostly heavy clays |

| Altitude | 640m |

| Diversification | 30h navel oranges, 40h Hass avos (plan to expand to 70h), 6 or 7 hectares tea tree (maybe go to 25h) in servitudes. |

While everyone else seems to be fighting to protect their turf, defending themselves against the elements, struggling with pests and generally squirming with discomfort, the atmosphere on this farm is calm, quiet and genuinely content. We still find all the normal farming challenges but here, they don’t sweat any of the ‘small stuff’. The objective is one of broad-based upliftment and, with that ambitious goal, no one can afford to waste energy on “noise”.

This comment summed it up perfectly, “We farm to grow people, sustainably, for generations.” For these farmers, it isn’t about the crop, it’s about upliftment – socially, environmentally, holistically. This philosophy could be played out in any industry, it just happens that these characters find themselves in a farming environment and so, it is here that they make a difference.

SO, HOW DID FARMING GET TO BE “THE MOVIE”?

Rewind back to the early part of last century when Chase Edmonds Snr. purchased the original family farm here in Table Mountain. He was not a farmer by trade or heritage, but with the support of his wife they settled into agriculture. Their sons, Jack and Don, continued the operation into the second generation. Jack’s side of the family tree grew impressively – 9 children! But it is Don’s side that gave rise to our current focus on Donovale where Ant and Chris Edmonds, Don’s sons, continue to farm alongside each other. There aren’t too many farming businesses, run by siblings, that have lasted for over 30 years. This is testament to a shared vision and recognition of each other’s contributions and a fairly large dose of humour.

Don Edmonds seems to have been the catalyst for a lot of what we see happening at Donovale today. The first clue is that he sent both his boys off to study Commerce at University, despite the fact that they were both going to be farmers. Already a “bigger picture” mindset is becoming evident. Ant fills in more of the picture when he explains that his parents were very forward-thinking – they taught the boys that farming in Africa necessitated a union with the people; it was never going to work if the people who worked the soil were mistreated or abused. Good labourers are more than a valuable resource; they are as important as the land owner, who cannot farm alone. Together, as one team, people can then steward the land for those who come after them.

From left to right: Simon Dombele, Chris Edmonds, Margaret Mamle, Sinodumo Ndokweni, Frank Ngomezulu, Ant Endmonds, Trent Payton and Lungelo Madiya.

From left to right: Simon Dombele, Chris Edmonds, Margaret Mamle, Sinodumo Ndokweni, Frank Ngomezulu, Ant Endmonds, Trent Payton and Lungelo Madiya.

DO THEY WALK THE TALK?

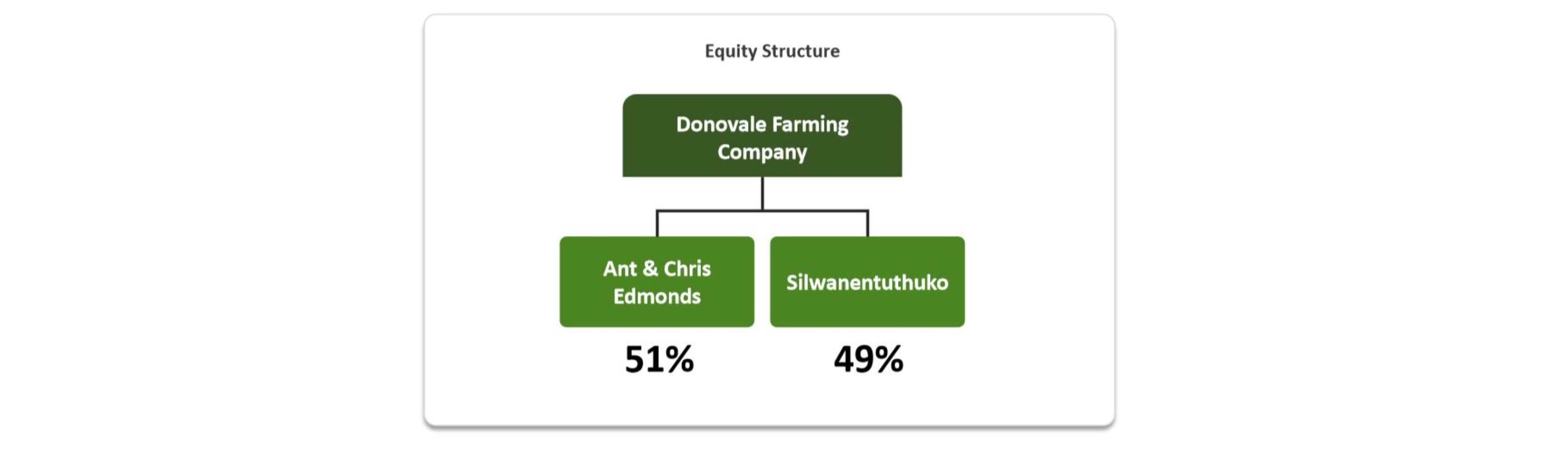

This leads us perfectly into how and why Donovale Farming Company (DFC) is structured currently. These men had a choice – to continue farming in the traditional model (white owner, black worker) or to switch to a more sustainable model, in this African setting. They assessed their personal aspirations which broadly encompassed these goals: Sustainable Land Reform, Community Upliftment, Acceptable ROI (returns on investment) and came up with this solution:

In a nutshell it involved selling the farm to the farm workers and then creating a management company (owned by Ant, Chris and the Workers) to run it. Not so revolutionary really if you consider one of the other highly probable alternatives was to effectively sell the entire farm and hand management over to people have limited farming knowledge. The Edmonds’ fostered a plan that’s going to work in the long-run. The unsustainable wealth gap, characteristic of most current farming models, is certainly under threat.

Without getting into the nuts and bolts a Trust was created, transforming 60 people from farm workers to shareholders and two other people, from Land Owners to shareholders. And now they all farm together. Sounds extreme and fraught with problems but Ant and Chris believed in their objectives enough to give it a whirl. In hindsight, there are things they would structure differently but overall the concept of everyone, working the land, having a stake in the business is core. Ant and Chris are happy to engage with anyone wanting insight into this model.

SHARING THE VISION

When sustainability is your driver, holism your context, and your world is not pinned in by convention, something like SUSFARMS is bound to pop out. It’ll therefore come as no surprise that farming sustainably is integral to this operation. I know that many farmers share my intimidation and limited knowledge of the concept so I have committed to dedicating an article to this topic in a month’s time. I plan to meet with stakeholders, break it down and chew it over in the interim so that I can deliver something that is relevant and useful … watch this space.

ENOUGH OF THE BIG PICTURE, LET’S LOOK FOR DETAILS …

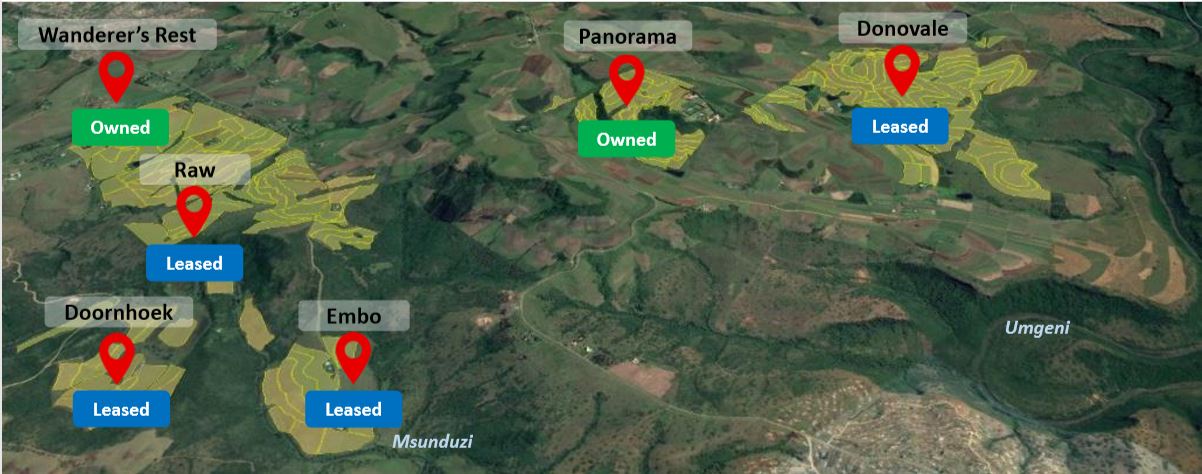

The operational model, established in 2007, is now focused on diversifying and developing the enterprise. The preference is for long term leases (75% of the business), with the security to extend, but some farms have been bought when that is the only option. Because the model fulfils the governments transformational requirements they have the prospect of accessing previously unavailable funding and opportunities, thereby enabling them to expand where they couldn’t before.

FALLOWING, PLANTING & FERTILISING

Fallow periods provide some relief from the draining effects of monocropping, but there is an obvious opportunity cost to the practice. DFC therefore does the best they can, even if it is just a short fallow.

First, the old crop is cleared with Roundup, which also kills all problematic creeping grasses. If we are getting a bit late in the season and there is no active plant growth then the Roundup will be skipped, in preference of the plough which kills off any determined cane. If the fields concerned have not yet undergone land-use improvements in terms of the SUSFARMS strategy, this is when they will be redone. Better land-use practices revolve around water management at the end of the day. The point of that is soil conservation. Once your top soil washes away, you have a 1000 year wait to get that top soil restored so keeping it in place is paramount. Water flow can be managed through adequate and effective waterways, crest and contour roads, and water catchment facilities like gabion baskets.

Once everything is laid out correctly. The field prep begins: on the flatter lands, a plough helps to dislodge the old stools. Matured kraal manure (at a rate of about 15 to 18 tonnes per hectare) is applied, followed by a disc which loosens the soil. Thereafter the fields enjoy a 600mm deep rip. Black Oats is the break crop of choice as it has great organic content, can feed the cattle and germinates easily, even late into the cooler months. It is also suppresses certain weeds; the allelopathic effect (a biological phenomenon by which an organism produces one or more biochemicals that influence the germination, growth, survival, and reproduction of other organisms), taking some pressure off the herbicide programme. A minimum tillage practice is followed on the steep fields as any mechanical disturbance increases the risk of wash away.

Once planting season rolls around, the oats are sprayed with glyphosate or disked in, the optimum soil tilth achieved by further disking if required, and furrows are drawn. 2:3:4, at a rate of about 250kgs per hectare, is placed in the furrows, along with double-stick placement of seedcane. The closing tool then adds a dose of Bandit before folding over the soil and rolling it down tightly.

Only once the cane has germinated will the herbicide spray programme commence. Top dress fertiliser, 50N at about 100kgs per hectare, will be applied in January.

When it comes to addressing acidity and other soil imbalances, SASRI recommendations are followed coming out of the soil samples submitted after every harvest.

TRUSTY OLD vs HIGH PROMISING NEW

Lately, there seem to be so many new options when it comes to varieties … and your appetite for risk is certainly tested. We know what the old stalwarts, like N12, are all about and sometimes that seems a bit ‘tame’ when the new varieties present their CVs. The problem is that a few have been known to underdeliver.

Ant has been disappointed by N47’s ratooning performance, especially as it arrived with the intention of taking over from N12. N54 was another option but it has been prone to smut, yellow aphid and Eldana attacks. It also lodges quite readily, often as early as 9 months. On the plus side; the shorter growing cycle of around 15 months is beneficial and it does seem to be improving its performance with every ratoon.

N54 cut in Dec (3 months old)

N54 cut in Dec (3 months old)

N61 and N62 are performing well thus far, from a P&D perspective at least. These trial fields haven’t been harvested yet so the champagne is nowhere near the ice. Agronomically, they have been performing as well as the N54, which is promising.

The new, shorter growing cycle varieties are proving to be a bit of a challenge in terms of syncing planting and harvesting with the seasons. This affects WHERE the new varieties are planted as some fields are inaccessible at certain times of the year. Another plus-point for the trusty old 24-month N12, which syncs perfectly with the 12-month calendar. It’s always a safe bet and it’s easy to understand why 68% of the farm is planted to it.

Although DFC’s currently running with an average of 4 ratoons before ploughing out, that figure has been swayed by the fairly recent new farm acquisitions on which aggressive replanting has had to be implemented. Normally, DFC would replant after about 6 or 7 ratoons, performance dependent.

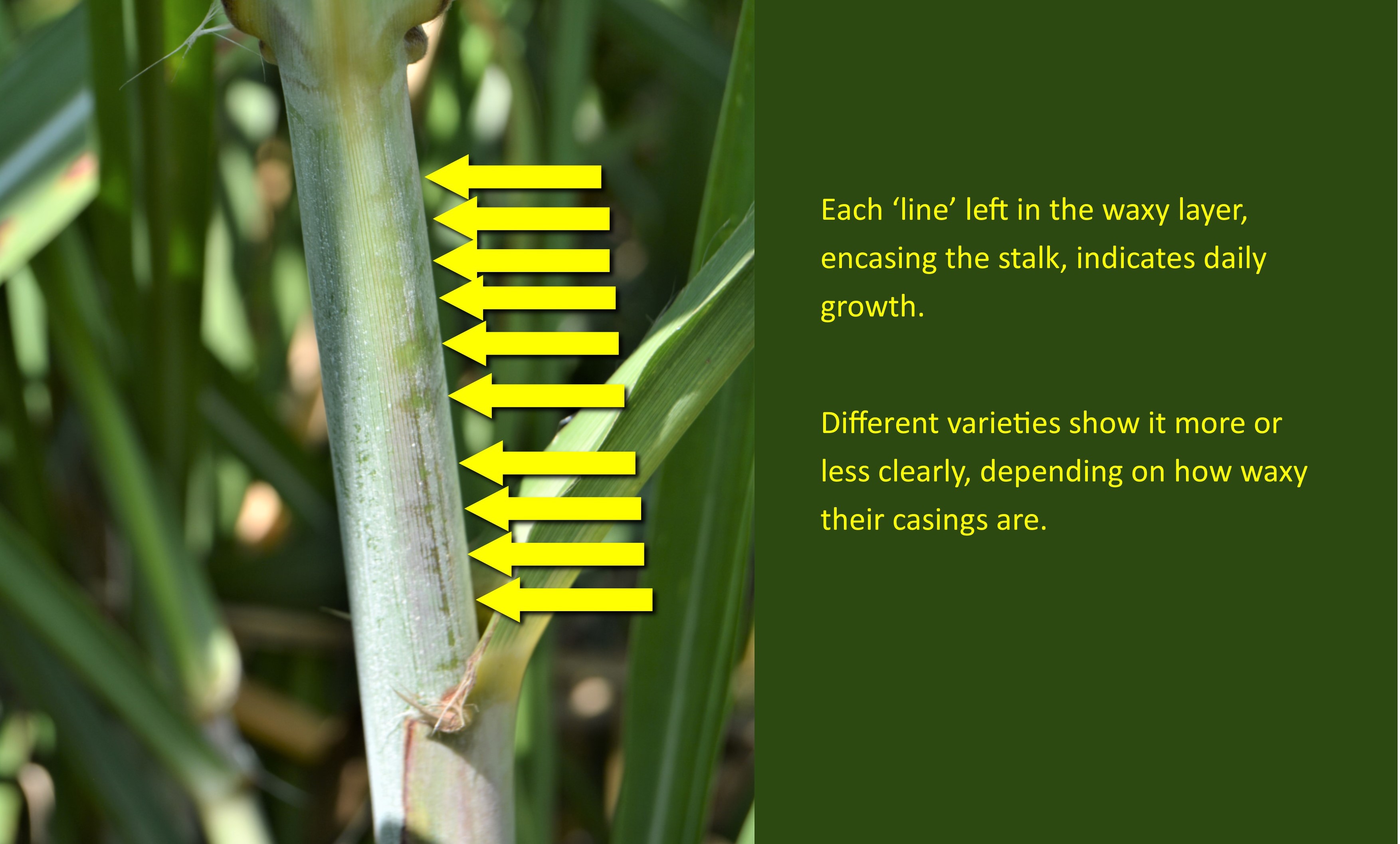

A wonderful observation I learnt whilst at DFC was the daily growth tracker most cane displays. Forgive me if all of you know about this but it has never been pointed out to me before:

Ant learnt this from the Noodsberg extension officer of the time: Quinton Mann, someone he says was an “agronomist of note” and a magnificent teacher.

IRRIGATION (Yes, we’re still in KZN)

Yup, it was very exciting to see irrigated cane and not have to travel 7 hours to get there.

DFC’s farms are very well positioned, straddling the watersheds of both the Umgeni and Msunduzi rivers. They’ve capitalised on this by irrigating about 100 hectares of sugarcane from the Msunduzi river. The varieties grown on these farms are N36 and N41.

A surface drip irrigation system feeds this cane from a pump house on the river. 300mm deep probes monitor moisture levels to regulate irrigation scheduling. The water in the river has come from areas surrounding Pietermaritzburg and therefore the quality is the biggest headache, both in terms of sediment and ecoli.

From top left, moving clockwise: The pump house, the filtration system, the drip irrigation piping, the Msunduzi river.

From top left, moving clockwise: The pump house, the filtration system, the drip irrigation piping, the Msunduzi river.

The filtration system works hard to keep the pipes free-flowing and flushes every hour for about 10 minutes. This irrigation system delivers 4600 m3 per hectare per year on top of the natural rainfall. All the cane under irrigation is on a 12-month growing cycle.

“Although drip irrigation is a low energy consumer, it is definitely not low maintenance,” scowls Ant.

Looking back up the hill, the break between the irrigated N36 and the dryland N12 is easy to see.

Looking back up the hill, the break between the irrigated N36 and the dryland N12 is easy to see.

This farm, leased from Umgeni water, is fully irrigated.

This farm, leased from Umgeni water, is fully irrigated.

Yields from these irrigated fields average at 97 tonnes per hectare, on a 12-month cycle. Ripening is essential and a piggy-back programme of Ethryl and Fusilade is used, applying as early as possible in a race to beat the frost which is common through the valley.

WORRISOME WEEDS

Most commonly, herbicides are applied in Spring but DFC advises that farmers should consider spraying in late Autumn thereby compromising the germination of most weeds, specifically Barbie grass, in Spring. Grass epidemics are almost always a consequence of poor timing rather than incorrect chemicals or application.

DFC sprays most plant cane by hand, thereby delaying mechanical compaction and allowing root systems to develop strong, robust walls before they have to endure the weight of a tractor.

PESTS & DISEASES

Here the war against P&D is waged using a multi-pronged approach including accurate timing, correct varieties (N66, currently being bulked up on this farm, is supposed to be eldana resistant!), balanced and broad biodiversity, chemical assistance and efforts to bolster natural ecosystems. Too many farmers rely on only one method of attack which may win one or two battles but the war will rage on. The whole issue of resistance building is also a negative consequence of single-pronged attacks.

Eldana

- Bat Hotel. DFC has installed a couple of these in the wetlands that have been planted up with natural eldana food. Bats are a natural predator and a vital link in the natural food chain.

The top pic is of DFC’s Bat Hotel in the wetland currently being cleaned up and stocked with lots of eldana delicacies. The bottom four pics are others that I pulled off the www. The box is not an onerous build and there’s no right or wrong, just a few guidelines which are easy to find on numerous helpful sites.

The top pic is of DFC’s Bat Hotel in the wetland currently being cleaned up and stocked with lots of eldana delicacies. The bottom four pics are others that I pulled off the www. The box is not an onerous build and there’s no right or wrong, just a few guidelines which are easy to find on numerous helpful sites.

- Melunus Minutiflora. This grass is a ‘push plant’ that emits a volatile scent which attracts natural enemies of eldana. The eldana borer moths pick up this scent and ‘get the message’ that it’s not a good place to lay eggs as the risk of predators is high.

Volatiles that eminate from the Melanus minutiflora serve to disrupt the flight paths of the eldana moths. This grass does require some management though, in that it should be doused with water to prevent burning during cane fires. It should also be mowed regularly as too thick a bed, resulting from late mowing, will almost certainly catch fire and kill the grass.

Volatiles that eminate from the Melanus minutiflora serve to disrupt the flight paths of the eldana moths. This grass does require some management though, in that it should be doused with water to prevent burning during cane fires. It should also be mowed regularly as too thick a bed, resulting from late mowing, will almost certainly catch fire and kill the grass.

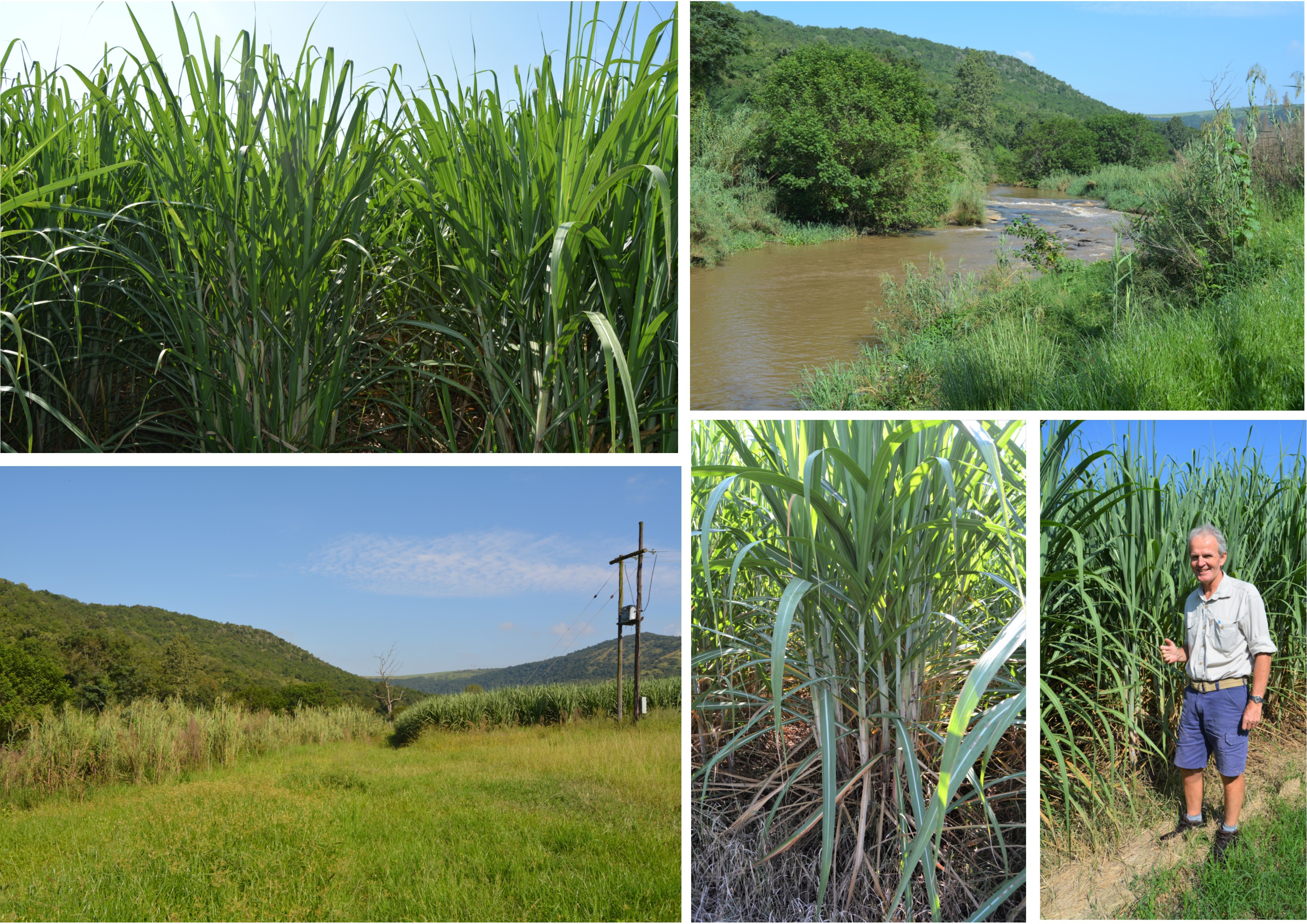

- Cyprus Papyrus and Cyprus Dives are two “pull plants” ie: they attract eldana. They are therefore good plants to include in any wetland ecosystem which are perfectly placed as passages alongside rivers and damp valley bottoms where cane does not grow well anyway. The natural area passageways become routes along which wildlife can traverse the farm safely while enriching the biodiversity. The EPWP (Extended Public Works Programme) has been very helpful to DFC, in providing labour to get the initial clearing for their rehabilitation projects done. The cyprus plants grow easily from slip so propogation is almost free. This all forms part of DFC’s integrated pest management approach to control eldana.

Left to right: Ant, pointing out the razor-sharp, serrated edges of the cyprus dives. Both cyprus dives and cyprus papyrus alongside each other in the newly established wetland, which is only a year old and already the bird-life was prolific the day I visited. Cyprus papyrus alone.

Left to right: Ant, pointing out the razor-sharp, serrated edges of the cyprus dives. Both cyprus dives and cyprus papyrus alongside each other in the newly established wetland, which is only a year old and already the bird-life was prolific the day I visited. Cyprus papyrus alone.

- Wild Bananas (Strelitzia Nicoli) are also being planted up in the natural passages. The bats sleep in the furled-up leaves of the wild bananas.

- Wasps. Another batch of these natural eldana predators were released on the farm the day before my visit.

The open veld, alongside the orchard, is becoming the headquarters for bug deployment. Yesterday, a batch of eldana-eating wasps were released. Bee hives also thrive on this hillside.

The open veld, alongside the orchard, is becoming the headquarters for bug deployment. Yesterday, a batch of eldana-eating wasps were released. Bee hives also thrive on this hillside.

- Sterile moths. The use of sterile eldana moths is an exciting possibility. The citrus industry makes extensive use of this sterilisation technology already. Apparently the challenge in this project is to get the right pheromone that will enable moths to be caught in order to assess the efficacy of the programme. Scientists won’t go ahead until the pheromone is available and “proof of concept” becomes a possibility.

Yellow aphids

It’s a regular Yellow Aphid party under this N62 leaf!

It’s a regular Yellow Aphid party under this N62 leaf!

The current epidemic of aphids in this area is perplexing. The trouble is, by the time they are found, much of the damage has already been done and the benefits of spraying vs the collateral damage of the insecticide is not positive. Again, a holistic approach needs to be formulated and followed.

SOILS

Much of the soil across these farms has a heavy clay content (>35%).

Much of the soil across these farms has a heavy clay content (>35%).

Heavy clay soils won’t share their moisture. If only 5mm rain falls into sandy soils, the cane there will be able to access it, not so if the soils are clay-heavy because this soil will hold onto a minimum water content, sharing only if there is excess available. That’s why, in really dry seasons, sandy soils may be better than heavy ones.

So, what can be done to increase organic matter and enhance soil health? DFC adds organic content, in the form of kraal manure, when planting. This is a logistically intense operation that requires fetching, carrying, storing, application and incorporation into the soil. But it does add a wide range of micro-elements like copper, iron and magnesium, and therein lies invaluable supplementation to support a healthy microbial subsoil environment. The high potassium content often means that only additional nitrogen and phosphorous supplementation is required.

And we later saw evidence that all that hard work is paying off when we found the king of organic life himself, and evidence that he is not alone (extensive worm ‘casings’)

And we later saw evidence that all that hard work is paying off when we found the king of organic life himself, and evidence that he is not alone (extensive worm ‘casings’)

Although adding kraal manure to every plant field is a logistically taxing process, the benefits far outweigh the costs.

Although adding kraal manure to every plant field is a logistically taxing process, the benefits far outweigh the costs.

HARVESTING & MECHANISATION

The climate here isn’t partial to the practice of trashing so all cane is burnt. The burns are kept as cool as possible so that the optimal balance between high organic content, good germination rates, acceptable costs and low cutter complaints is achieved.

Ergonomically, cane cutting is the most difficult job there is. DFC runs both cut-and-stack operations and cut-and-windrow, depending on whether equipment can access the field efficiently. All plant fields are stacked to minimise early compaction and allow cane roots to get a solid start.

It is very important to the DFC team that cutters are adequately equipped to perform this epic job; both in terms of nutrition and tools. Nutritionally, both in-field supplements as well as a hot meal at night is provided. The day I visited was the first day they were trying out a new product, called Yabhusta, as an energy-packed infield drink. Large Wonder cooking bags will now provide an energy-efficient way to prepare veggie-packed stews for the evening meal.

In this shot we can see both operations happening; C&W in the foreground and C&S in the background. By getting all cutters in, they made sure that everything got to the mill before the pay weekend.

In this shot we can see both operations happening; C&W in the foreground and C&S in the background. By getting all cutters in, they made sure that everything got to the mill before the pay weekend.

I’ve always known that burn to crush time needs to be as low as possible but I hadn’t known the science behind it: apparently, the cane continues to grow temporarily, even after harvest and, because there are no roots from which to draw sustenance, the cane will start metabolising its own sucrose to fuel the growth. Therefore, the longer you leave it, the poorer the quality. By the 100-hour mark, you’re down R25 per tonne. No one should be going over 50 hours unless there are irregular circumstances.

DFC has their own truck, made possible by the economies of scale that over 40 000 tonnes annually allows. This truck works 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with 3 drivers. It does 100 000kms per year and is replaced every 4 years. 30 000 tonnes annually should justify a rig and that’s why DFC doesn’t have 2 … instead, they contract in a second truck to take the additional cane at the height of the season.

The Donovale Farming Company rig – a hard-working member of this dynamic team.

The Donovale Farming Company rig – a hard-working member of this dynamic team.

TECHNOLOGY

Trent, Ant’s son-in-law, has a natural affinity for everything tech and his financial degree has brought immeasurable value to the operation. Having someone look at things in a fresh light has been a game-changer in many spheres, especially when it comes to leveraging available technologies and efficiencies. A small example is the new way of analysing fuel use; DFC now captures data at the pump which provides clean, comprehensive, relevant information that can be used to make decisions, pick up discrepancies and improve where necessary.

Another useful tool has been the APP/web-based tracking tool that DFC now uses on all knapsacks and tractors. It generates a full report of movement and activity allowing them to see where teams are, for how long, what the movements were, when a pto is engaged etc. They use the data to track progress, assess productivity and verify application rates. It’s not expensive at all and has been very helpful.

Google Earth Pro is another tool that does not cost anything but has been invaluable, as a base, in creating farm layouts which is the foundation for other applications used in running various farm activities. The whole team can now be sure they are “on the same page”, enhancing the accuracy and relevance of data.

Google Earth Pro has been used as a base to map all farms as well as name and size each field accurately.

Google Earth Pro has been used as a base to map all farms as well as name and size each field accurately.

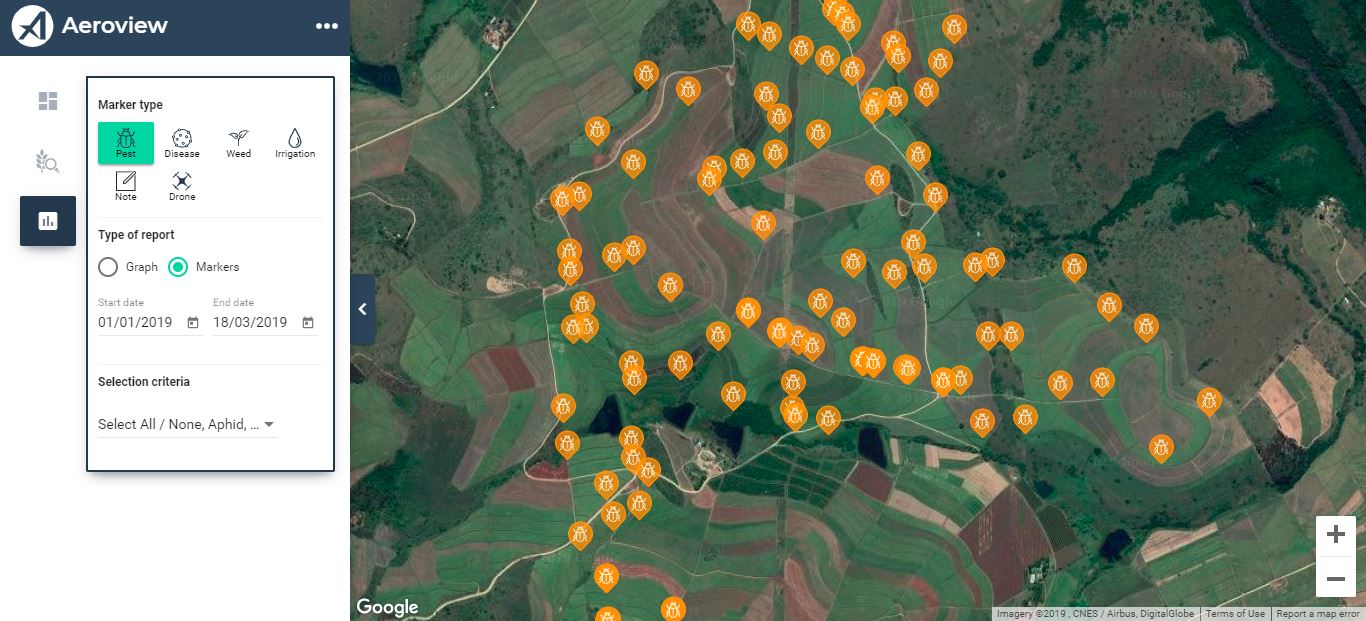

Another app that has proven incredibly useful for P&D programmes is supplied by Aeroview, called Aero Scout. A hand-held device is loaded with locations (set by DFC through GPS coordinates) from which a P&D count is required. The scouters are directed to the relevant place in each field, by the device, and once they’re there, they do the count, input the results and move on to the next point. It’s revolutionised the accuracy and independence of the scouting teams which, in turn, has enabled management to make better decisions from the improved data.

The orange markers are the management-selected points. Now the scouting team will go to each point, count, input data and move on. By going to the same point each time, trends and patterns can be established, facilitating better responses in the P&D programme.

The orange markers are the management-selected points. Now the scouting team will go to each point, count, input data and move on. By going to the same point each time, trends and patterns can be established, facilitating better responses in the P&D programme.

DIVERSIFICATION

DFC does a lot more than farm people and the odd tonne of cane. There are also just over 30 hectares of navel oranges, 40+ hectares of Hass avos (with plans to expand to expand to about 70 hectares) and around 7 hectares of tea tree (maybe go to 25 hectares). All indicators are that sugar is going to become a difficult crop to survive on and anyone operating a substandard operation will probably be shaken free of the industry.

DFC farms are perfectly positioned in a transitional zone between coastal and inland climates. This gives them a broad choice of crops that will thrive, as is indicated by the 140 different tree species across the properties. Previously they have dabbled in tomatoes, papinos and pincushion proteas.

DFC’s tea tree will be going into its 4th harvest this year. It grows well in the powerline servitudes, doesn’t require irrigation and is producing well.

DFC’s tea tree will be going into its 4th harvest this year. It grows well in the powerline servitudes, doesn’t require irrigation and is producing well.

Baby avos, recently planted, have been mulched with cane tops. In between the rows a special grass mix has been planted to host the necessary biodiversity that will help control harmful insects.

Baby avos, recently planted, have been mulched with cane tops. In between the rows a special grass mix has been planted to host the necessary biodiversity that will help control harmful insects.

Oranges will undergo the greatest expansion if DFC receives the necessary funding.

Oranges will undergo the greatest expansion if DFC receives the necessary funding.

A FEW POINTS ABOUT THE FUTURE

- Leadership at DFC: For an organisation that is so pivotal to not only the shareholders involved but also the earth that it caretakes, the future plans are of paramount importance. When it comes to people, the current management works hard to build a strong core of people that will come through the ranks to lead competently into the future. Current leadership make sure that they continuously download all their expertise and consequently make themselves more dispensable.

- Political stability: When asked about the agricultural future of South Africa, Ant told me about a trip he went on recently; he was invited, along with 10 other farmers, to ‘have a chat’ with David Mabuza, our Deputy President. The aim was to discuss solutions and a way forward in the agricultural sector. Mr Mabuza conceded that they’ve done much wrong and they’d really like to stabilise the future with a sustainable plan. Ant left feeling positive.

- Open doors: DFC has a very open view to their land and would like to emulate the British ‘free to roam’ philosophy where you can traverse any land, on specified paths which the land owner has to maintain. Our unique African charm means this may be easier to dream about than implement but respectful, well-behaved walkers, runners, cyclists, horse-riders and fishermen are welcome to enjoy DFC land.

- Showcase transformation. Margaret Mamle (on the current Board of Directors) has been mentored by Chris and she plays a big role in the horticultural side of the business. Simon Dombele (also on the current Board of Directors) has been involved on the cane farm all his working life and is in charge of cane extraction and logistics. Frank Ngomezulu (Chairman of the current Board) was always the operation’s best cane cutter. A few years back he expressed his ambition to go further and now manages the cutting force. All leadership have to have an ability to nurture and maintain relationships as DFC is a unique organisation with special needs for this skill.

TIME TO REFLECT

While we were driving around, Ant and I kept fighting the urge to do BWAs (bakkie window assessments) and when I thought about it later, that helped me understand so much of the bigger picture: we’re all lazy and want to do things the easiest possible way, despite all those inspirational quotes reminding us that “nothing worthwhile is easy”. If we farm that way (the ‘easy’ BWA way) we may stay clean and get back home in time for breakfast but it’s just not sustainable. We HAVE to get out, get dirty, get involved, and probably be late for breakfast, if we want this gig to last into future generations. What DFC are doing with all the practices and company structures they follow, is to get out, get dirty, get involved and thereby ensure that this land has the best possible chance of making a difference for many generations to come. Well done everyone, and thank you for showing me the alternative to BWAs.

I was grateful to have been shown this special ‘registered site of conservation significance’, overlooking the Umgeni river. Whilst surveying the view, Ant shared the weight he feels in being a custodian of this breath-taking part of the earth. But I am relieved that the burden has fallen to someone like Ant – in fact, I haven’t met many men that I’d be more willing to leave the planet with.