| Date interviewed | 7 March 2019 |

| Date newsletter posted | 8 April 2019 |

| Farmer | Gary Behn |

| Farm name | Bennidale |

| Mill | Noodsberg |

| Distance to the mill | 50kms |

| Area under cane | 356 hectares |

| Other crops | Wattle, tea tree, cattle |

| Tonnes to mill | 16 000 tonnes annually |

| Cutting cycle | Average 22 months |

| Av Yield | 90 tonnes/hectare |

| Av RV | 13.04 % |

| Varieties | 39, 41, 48, 52, 54, 12, 37 |

| Av rainfall | Higher altitude: 875mm. Lower altitudes: 650mm (Jan 2019 was the lowest rainfall ever recorded) |

| Soils | Mispahs, Shortlands, Glenrosas, Huttons |

I can be a bit of a starer. My kids will often shake me from fixated fascination when I forget that I am an adult and it’s not polite to stare. But I am sure you’ve all found yourselves faced by a phenomenon from which it is difficult to tear your eyes? Whilst I didn’t stare at the Behn family (I was there too long) I was mentally captivated for the entire visit, as I hope you will be by their story.

Gary and Claire Behn, together with Gary’s parents, John and Stella, and children, Murray and Jess, are an amazingly close unit who appear to be bountifully blessed. But when you scrape beneath the surface you realise that no situation is perfect and it’s attitude that makes all the difference. The entire Behn clan seems to have an overwhelming attitude of gratitude that tricks you into believing that they live in Utopia.

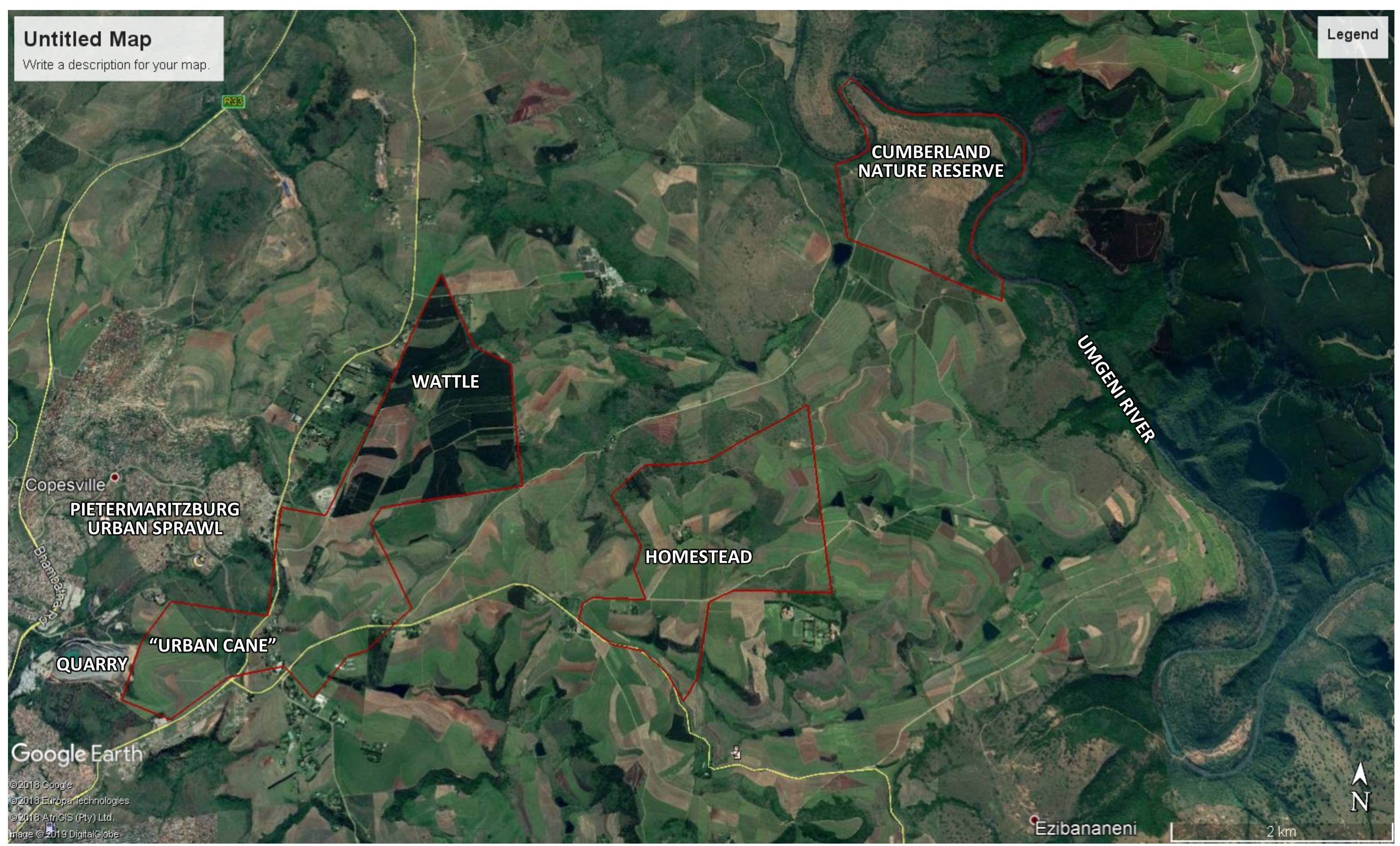

In reality, they live in the Table Mountain area, just outside Pietermaritzburg – well, parts of the land they farm is practically IN Pietermaritzburg – but we’ll get to that.

HISTORY

In 1848 the Bure family landed in South Africa as a part of the brave German contingent who settled New Germany, near Pinetown. Here they farmed cotton and established a thriving community. In September 1910 Gary’s great grandfather, Gustav Bure, married Johanna Thole, from the same German unit. In 1908 he had purchased “Ekukanyeni” from the Colenso Trust and thus they came to settle in this area, close to Table Mountain, Pietermaritzburg.

The first buildings were constructed in 1910 and include this tin shed, pictured below. Not shabby, considering that it is now almost 110 years old!

The early faming activities were typical of the time, dairy, maize, potaotoes, wattles, etc and an attempt at growing cotton, which was unsuccessful. Then, in the 60’s, the same intrepid bunch that we met in the Eggers’ chapter of SugarBytes proved the naysayers wrong. Perhaps great grandfather Eggers shared a toast with great grandfather Bure … ?

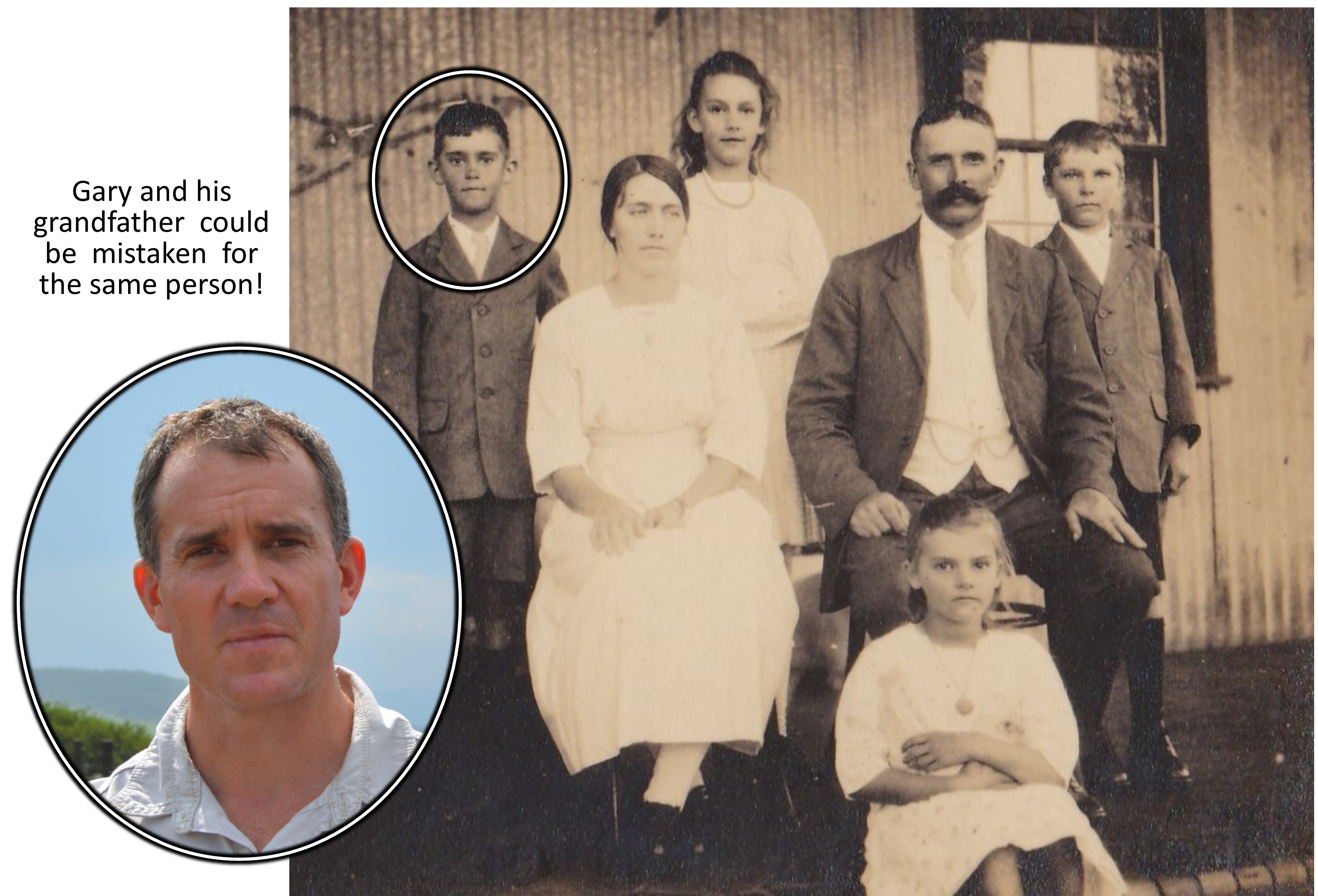

Friedhold Bure (Gary’s grandfather), his older sister Thea, his older brother Edgar. Middle: Gary’s great grandparents, Johanna Bure (born Thole) and Gustav Bure. Seated in the front is his youngest sister, Anita.

Friedhold Bure (Gary’s grandfather), his older sister Thea, his older brother Edgar. Middle: Gary’s great grandparents, Johanna Bure (born Thole) and Gustav Bure. Seated in the front is his youngest sister, Anita.

Friedhold Bure took over the farm from his Dad and then passed it on, in 3 equal portions, to his daughters, one of whom is Gary’s mom, Stella. One of the girls sold her portion to her sisters and thus the original farm was only divided in two. Stella married John Behn and so her farm came to be known as Bennidale.

In 2008 a blanket claim was gazetted in the area, including all agriculturally viable parts of Bennidale, but progress on it has been slow and Gary is committed to working with the claimants should it go through.

Table Mountain in the distance with Gary’s cane fields on the near hillside.

Table Mountain in the distance with Gary’s cane fields on the near hillside.

FAMILY

Gary has two sisters; one has married a livestock farmer and lives in Middelrus. His younger sister, Wendy, has her own business and is involved in the financial side of Gary’s operation.

After school, Gary travelled overseas. He’d been abroad for a year when family responsibilities necessitated his return. Although he’d attended Weston Agricultural College, he had a lot to learn about farming and is very grateful that his Dad afforded him the independence to learn through experience; some parents find it difficult to relinquish control, making transition to the next generation challenging. That wasn’t the case here and that probably accounts largely for the contented environment uniting a few generations.

Cumberland formed a large part of the property and cattle had always been ranched here. As Gary was passionate about conservation, he got stuck into turning this into a Nature Reserve; he built ablutions and picnic sites and erected game fences. Once it was set up, Gary and John swopped places with John and Stella moving onto Cumberland to run the Nature Reserve and Gary moved into the chief farmer role. Gary was wonderfully supported by neighbours as he began facing the practical challenges of farming cane profitably.

Gary, Claire, Murray and Jess

Gary, Claire, Murray and Jess

Claire is a qualified teacher but spent the early years of their marriage assisting in the administration of the business. She then taught Gr 1 at Merchiston Primary for 8 years and has only just been recalled to support the growing family business. She doesn’t have a job description yet but is focusing on making the large-scale and diversified operation more manageable for Gary by overseeing Cumberland now that John and Stella are enjoying a more relaxed (dare I say ‘retired’) life.

Murray is in Gr 10 and his academic nature is probably more inclined to follow a path in agricultural economics than get-your-hands-dirty farming. He just completed his first Duzi with Gary, who now has 24 of them under his belt. Jess is in Gr 7 and full of farming enthusiasm – anything to be out and about with Dad.

GEOGRAPHICAL CHALLENGES

When Gary first said, “We farm in very different conditions here” I have to admit that I didn’t fully appreciate just how different they are or how big an impact the urban proximity makes to the way they farm. The theft, fire risk and safety issues that come with bordering humanity are extreme.

80 of Gary’s 356 hectares under cane are subject to these issues. In fact, Gary loses up to 30 tonnes per hectare here to theft. If he polices it and imposes consequences, instead of controlling the issue he raises another one – arson. He’s tried to plant hairier varieties but they’ll either harvest that anyway or walk to the adjoining field. The theft is blatant and I witnessed it first hand when we drove around the farm. A couple of the thieves at least had the shame to disappear deeper into the cane but one young man stood his ground, knowing there was nothing Gary could, or would, do. I found it deeply disturbing and sad to observe and can scarcely understand the serene calmness Gary demonstrates. The stolen cane is sold for R5 per stick. Gary gets about 40c per stick from the mill so he has even considered entering this alternate market himself … of course, it’s never that simple. Instead he just accepts the loss and farms this 80 hectares differently: no night work, nobody works alone, no trash blanket – even the tops are burnt, opening the season with this mature cane to get it out before it is set alight prematurely, a constant fire-fighting vigil on hot and windy days, strip planting to minimise the effects of runaway fires. Ie: best agricultural practices are set aside to serve the practice of survival. As they face a ridiculous number of accidental/arson fires each season, Gary doesn’t even bother to submit smaller insurance claims anymore. The wholesale dumping of waste on this farm also means that Gary has to send a front-end loader to clear roads into the farm before he can access and harvest.

He does express his gratitude for his neighbours though – many of whom are closer to this frontier than his homestead is – they are always so quick to respond and help to extinguish the trouble. There’s certainly something special about this relatively small farming community west of the Umgeni river. There are only about 8 commercial growers here and in Micheon Ngubane’s SugarBytes story last month we were all warmed by the support he received in this community as a new-comer. I have learnt that he’s not the only one – it seems that help and support is free and bountiful in Table Mountain.

If urban proximity could be traded with mill proximity, it would help … Bennidale is an average of 50kms away from Noodsberg mill. This is the edge of feasibility when it comes to a viable distance to transport cane, and it’s uphill most of the way! But Gary smiles and says “It sure does make us more efficient.” No one is fat and lazy on this farm. Neither is anything superfluous on the schedule; if it doesn’t make a difference to the bottom line, it is probably not going to happen. And this does not sit easily with Gary; he would love to be able to enjoy manicured lawns and cleanly weeded plantations. While he’s telling me this I am wincing at the thought of how acutely the low cane price must be impacting Gary’s already stretched finances. But, true to form, he points out the positives: Illovo’s new Grower Incentive Scheme that has been offered to all their growers, from Noodsberg to Umzimkulu, means that he will not be taking any cane out. Illovo has offered to pay, upfront, for cane supply over the next 5 years. This is over and above the normal remuneration for cane delivered. This incentive could be the only reason some cane farmers survive the current price crisis.

DIVERSIFICATION

300 hectares of Bennidale has been committed to Cumberland Nature Reserve. Fences have been dropped to incorporate another 300 hectares of Donovale Farming land and this expansive sanctuary has been open to the public for 20 years now; offering picnic sites, accommodation, fantastic game and much more. I plan to escape there with my family and spend hours walking the extensive retreat as soon as I can. I have been assured that, whilst there is plenty of game, none of them have incisors. And the reserve is less than 30 minutes from central Pietermaritzburg – at last an upside of urban proximity.

The 20 minutes we spent whizzing around Cumberland was enough to convince me that this as somewhere I wanted to bring my family. See you again soon Cumberland …

The 20 minutes we spent whizzing around Cumberland was enough to convince me that this as somewhere I wanted to bring my family. See you again soon Cumberland …

Then there’s 202 hectares of wattle. This syncs nicely with the cane in terms of labour requirements. Ordinarily, it is a supplementary income but, with current sugar prices, it’s actually going a fair way to sustaining the whole operation.

Wattle is stripped on the farm and the timber exported to Japan in wood chip form via marketing agent, NCT. The bark is processed at UCL. This farm used to be a research facility so seeds are still harvested here, by an independent operation, and used to germinate seedlings to supply to foresters.

Wattle is stripped on the farm and the timber exported to Japan in wood chip form via marketing agent, NCT. The bark is processed at UCL. This farm used to be a research facility so seeds are still harvested here, by an independent operation, and used to germinate seedlings to supply to foresters.

The 100-strong Brangus-X herd doesn’t contribute very much to the bottom line but it does provide what Claire calls Gary’s ‘bovine therapy’. I instantly smile as I remember how therapeutic watching those calves could be. The Nguni herd, with the impressive Ankole bull is another wonderful feature of the farm.

Last, but most importantly, is the tea tree element of Gary’s diversified portfolio. It’s a new adventure that he’s tentatively enjoying; whilst it is exciting to be dabbling in something new and different, it is also stressful. There’s very little literature on how to farm it successfully and no one is terribly keen to share openly at this stage. Probably because the size of the essential oils market is not clear. This leads to uncertainty for farmers who have already committed resources to it as well as those considering taking the plunge. If supply exceeds demand, those in the game may realise diminished returns. Until market security (a buyer for your product at a good price) is established, everyone’s going to fly below the radar for fear of destabilising a currently lucrative crop. The exciting features, for Gary, is that this crop is fire resistant, doesn’t require irrigation, cows and goats don’t eat it, people don’t steal it and it doesn’t require specialised equipment. Given that this covers many of his specific challenges, he’s nervously excited about the future of essential oils in his operation.

Another advantage of the tea tree is that it can be grown in the power line servitudes.

Another advantage of the tea tree is that it can be grown in the power line servitudes.

CANE FARMING

In 2012, Gary took on some new leases. Prior to that his annual quota was 9000 tonnes and he produced an average yield of 106 tonnes/hectare with an average RV of 13.75%. Most of his soils were shortlands, glenrosas and huttons. The leased farms have come with poorer soils; mispahs and glenrosas. Although he is now delivering 16 000 tonnes per annum, the yield and RV has decreased slightly. With the arrival of new varieties, he has managed to decrease the average crop cycle from 24 months to 22 months. Gary has been using CanePro since 2000 and it has been an essential tool in tracking farm productivity and progress. This information facilitates informed decision-making. Poor weather, over the last few seasons in particular, has been largely responsible for the overall declines shown on the graphs, despite new varieties performing well.

Gary shows me some of the particularly poor mispah soils he contends with on the ‘new’ farms.

Gary shows me some of the particularly poor mispah soils he contends with on the ‘new’ farms.

Cover crops: There’s a couple of reasons that Gary has not been able to follow a consistent practice of cover cropping: 1. Simple economics – fallow periods don’t generate much needed income. 2. Some fields are too steep and no-till practices are followed; hand planting a cover crop is not economically viable. Here, dead cane stools and weeds are incorporated into the soil as organic matter. 3. Gary is following a revised schedule (see below) that would see cover crops get into the soil too far into winter to produce anything worthwhile.

If the field is overdue a short holiday, it will be most likely be a maize-vacation. This crop has a nice short growing cycle, is good for eliminating cane stools and it provides the cattle with some sustenance, it does not, however, contribute very much green matter to the soil.

These fields are too steep for mechanisation and enjoy minimum-tillage. Presently they are lying fallow until Spring.

These fields are too steep for mechanisation and enjoy minimum-tillage. Presently they are lying fallow until Spring.

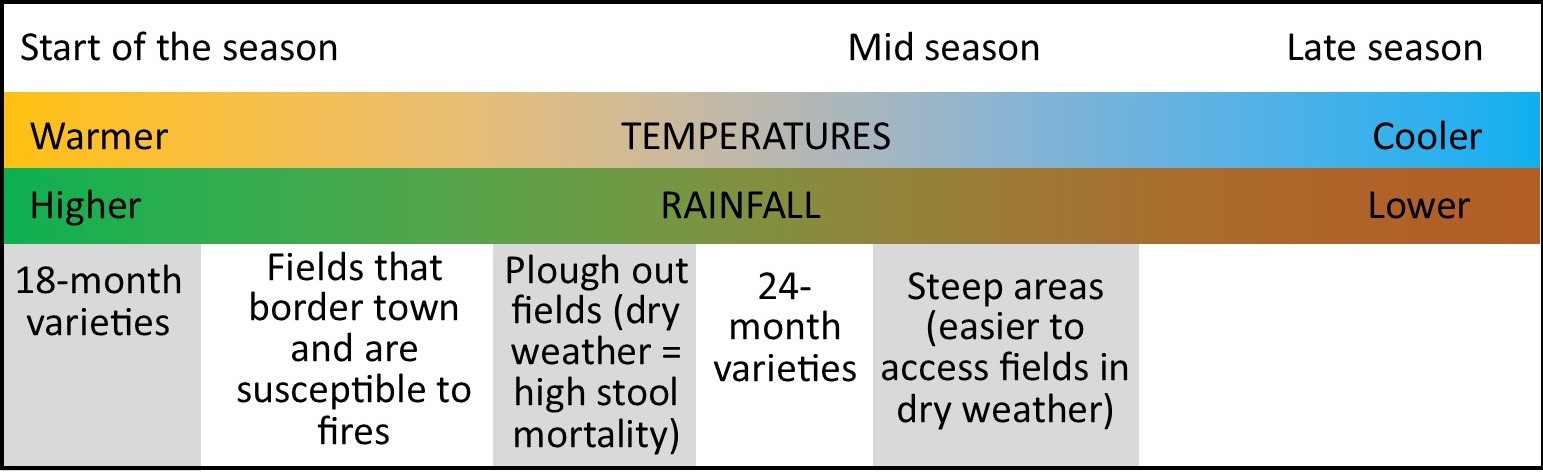

New harvesting schedule: Historically, this has been a 24-month farm but some of the new varieties are being cut at 18 months, dropping the overall cycle down to a 22-month average. N12 is a stable staple on Bennidale and will always require a full 24 months and keep the average higher. These quick growers have made Gary rethink his schedule; he used to open the season with fields to be ploughed out that year. They’d be ploughed out and lie fallow for winter to be replanted in spring – standard practice. But, for the last 5 or 6 years, he’s found that it works better to open with the new, short-cycle varieties (N48 & N54 mostly) in March and April. They then start to ratoon nicely, well before winter, giving him a head start. The plough-out fields are then attended to in May, when rainfall is less, and stool mortality is therefore better.

So, this is what the new schedule looks like:

Sampling & Fertilisers:

- Almost every field is sampled after every harvest. Gary has the greatest respect for SASRI’s advice and follows their recommendations closely.

- The soils in higher rainfall areas of the farm seem to require lime and gypsum occasionally whereas the lower rainfall areas don’t. Perhaps this has more to do with previous agricultural practices in different rainfall regions or perhaps it is the leaching of minerals from the soil.

- 8 tonnes / hectare of chicken litter is applied to every plant field. Gary collects this from a neighbour’s chicken sheds weekly and either stores it or uses it fresh. This is broadcast and disked in, supplementing soil nutrients and organic content.

- Granular fertiliser is used in the furrows when planting, according to SASRI’s recommendations. Usually 2:3:4 at 200kgs/hectare but sometimes MAP is suggested.

- On the heavy soils (50-60% clay) top dressing for plant cane is normally 100kgs of Urea. If a sandier / poorer soil is involved, LAN and split application strategies would be considered.

- Gary emphasises that fertiliser should only be applied if the cane is growing actively.

- CMS is “Rolls Royce” according to Gary but he’s not sure it justifies the extra expense, which he has calculated to be about 20% more than granular … he’s not convinced that 20% more income is netted by using CMS over granular. He does agree that it is better for soil health and has long term benefits in that regard. On the down-side, soil compaction of the large tractors and tanks concern him. On the upside, the convenience of ordering CMS and sitting back is attractive.

Varieties: Gary is applying himself to the exercise of finding site-suitable varieties for every field. The challenge here is a multi-horned beast; if a variety fails is it going to fail elsewhere? If a variety flourishes, is it going to continue to perform through enough ratoons to make it viable? Is the failure / success of a crop due to the variety or the weather or some other anomaly in the mix? The answers to these questions take time and detailed record-keeping. The latter is handled well but time is something we’re all short on, especially when there will be new varieties out by the time you assess the current ones adequately. Mulling this over, I fully understand why Gary resorts back to trusty old N12 when he’s unsure about what’s going to work well in an environment and why this trusty old stalwart makes up 65% of Bennidale’s cane. Although SASRI is concerned about the P&D risks of older varieties, Gary is comforted by its bullet-proof constitution.

His caution was justified by N29’s behaviour; in its first year it produced 129t/h. The following year, almost the same. The celebratory party was convened in the third year and everyone turned up, including N29, dressed in ORANGE …. RUST!! Needless to say, the party ended early and N29 was sent packing. N37 also disappointed when its lack of stamina resulted in a drastic drop in yield a few ratoons in.

Whilst there’s no sign of champagne, Gary is cautiously excited about N48 and N54 at the moment.

Even when you know someone’s parents, it doesn’t mean you can trust them; N47 is a descendant of N12 but it hasn’t performed well and Gary is busy packing its bags too.

N35 was also a great variety initially, with exceptional RV, but its soft structure made it an eldana delicacy.

Currently under trial is N41 – Gary is trying 3 hectares in shortlands soils on a low rainfall side of the farm. He’s hoping for 90t/h with a high RV. Given that the mill is so far away, light but rich cane is a winning recipe.

This pic gives a nice comparison of N52 plant crop on the left, 18 months old. Gary says that this does really well on marginal soils. On the right is N41, also 18 months old but 4th ratoon. The RV in this field will be higher than the N52 but the yield will be lower. As Gary says, he’s farming tonnes of RV not tonnes of sugarcane so it will be interesting which field brings home more bacon.

This pic gives a nice comparison of N52 plant crop on the left, 18 months old. Gary says that this does really well on marginal soils. On the right is N41, also 18 months old but 4th ratoon. The RV in this field will be higher than the N52 but the yield will be lower. As Gary says, he’s farming tonnes of RV not tonnes of sugarcane so it will be interesting which field brings home more bacon.

And then there’s the consideration that N52 doesn’t seem to be able to pace itself through dry spells, and it requires ripening. When Gary adds that crop cycle also needs to be factored into the equation, my mathematical capabilities maxed out. Who knew farming required a maths degree!?

N52 was used in these fields because the soils are so poor but Gary took it out after the first ratoon as it just seemed to burn itself out; pacing itself in poor environments seems to be an issue. He is now trying N12 but, if that fails, the fields will be abandoned for now, like the top fields. Some soils just can’t sustain anything …

N52 was used in these fields because the soils are so poor but Gary took it out after the first ratoon as it just seemed to burn itself out; pacing itself in poor environments seems to be an issue. He is now trying N12 but, if that fails, the fields will be abandoned for now, like the top fields. Some soils just can’t sustain anything …

From the line-up above, it’s easy to see why Gary is partial to the stocky N48. This stick was taken from a first ratoon, 18-month-old field. He’s been growing N48 for 5 seasons now and it is starting to show signs of decline from the initial 130 tonnes per hectare. Another challenge is that the high sucrose makes it a favourite for everyone; eldana, people, bush pigs …

From the line-up above, it’s easy to see why Gary is partial to the stocky N48. This stick was taken from a first ratoon, 18-month-old field. He’s been growing N48 for 5 seasons now and it is starting to show signs of decline from the initial 130 tonnes per hectare. Another challenge is that the high sucrose makes it a favourite for everyone; eldana, people, bush pigs …

Gary has only been farming N54 for about 2 years now so it hasn’t yet proven itself but, thus far, it is looking even better than N48 in terms of yield and sucrose. It also doesn’t seem to be as prone to eldana, pigs or people. Above Gary is standing alongside a 16-month old field.

Gary has only been farming N54 for about 2 years now so it hasn’t yet proven itself but, thus far, it is looking even better than N48 in terms of yield and sucrose. It also doesn’t seem to be as prone to eldana, pigs or people. Above Gary is standing alongside a 16-month old field.

N41 is also a very sweet variety. Gary pointed out the extensive porcupine damage that was apparent in this field, about to be harvested.

N41 is also a very sweet variety. Gary pointed out the extensive porcupine damage that was apparent in this field, about to be harvested.

Pests and Diseases: Gary is very cautious about using pesticides. Thrips are controlled by spraying sets in the furrow, everything except N12, which doesn’t seem to be as susceptible (yet another point in the N12 column …)

Eldana, although present on neighbouring farms, has not yet been found in Gary’s cane. He wonders whether it is because there are no natural habitats for it or just that they prefer the valley bottoms and his farm is mostly at a higher altitude. Regardless, he has his own guys scout at least twice a year and the P&D guys also scout every six months, just in case things change.

N37, N41 and N39 seem to be susceptible to rust and require spraying.

Herbicides: Two points are highlighted from this discussion:

- As long as is financially possible, Gary will avoid using generics. The high cost of labour means that the job HAS to be done properly, the first time.

- Timing is the single most important factor in the successful management of weeds. It is so easy to spray too late and there’s no harm in spraying a little early so spend time in the field rather than making decisions based on the calendar; see what is making an appearance and knock it back before it gets out of control. Using pre-emergent products is important, followed by a quality, long-term chemical.

Gary usually invests in 2 manual hoeings in a year – one before closing and one after Christmas, this usually sees him through the worst of the weeds. He targets plant fields and newer ratoon fields because they hold the most potential. It’s easy to spend time and money in weaker, older fields because they need it more but Gary advises that farmers should always consider the return on investment when spending time and money on a field. In his experience, the greatest returns are received from looking after the younger fields.

January was the driest month ever recorded by Gary. This Thithimbila (aka drought weed) has loved it and these shallow glenrosa soils are perfect for runaway epidemics of this problem. Gary laughs that Claire has been raising her eyebrows, and questioning him, whenever she drives past the unusually scruffy scene.

January was the driest month ever recorded by Gary. This Thithimbila (aka drought weed) has loved it and these shallow glenrosa soils are perfect for runaway epidemics of this problem. Gary laughs that Claire has been raising her eyebrows, and questioning him, whenever she drives past the unusually scruffy scene.

Labour: If I was a labourer, I’d chose to work here. I could tell, before I was even told, that this family goes above and beyond the duties of an employer when it comes to staff welfare. Gary blames his mom and says that she’s spoilt everyone by being a nurturing mother to the entire workforce and created a culture of intricate involvement that he feels he should maintain. He admits that people are the toughest part of being a farmer but is feeling more ‘in control’ now that he has a quality core team around him; Claire (minister without portfolio), Eurika – Bennidale’s book keeper, about whom Gary couldn’t stop raving, Gareth and Candice – who have taken over management of Cumberland, and his two wing-‘men’ supervisors; Simphiwe and Funeka.

Simphiwe (left) and Funeka (right). In the centre are the farm’s three best cutters. Gary says they are capable of 15 tonnes per day EACH, cut and windrow, when they get the urge to put in a 12-hour day. Gary’s respect for these ‘endurance athletes’ is immense.

Simphiwe (left) and Funeka (right). In the centre are the farm’s three best cutters. Gary says they are capable of 15 tonnes per day EACH, cut and windrow, when they get the urge to put in a 12-hour day. Gary’s respect for these ‘endurance athletes’ is immense.

There are 51 permanent employees. All staff, cutters included, are full-time, year-round. When the cane is cut, they move into ratoon management or the timber plantations.

Gary concedes that, when it comes to employees, Bennidale is far more of a socialist environment than a capitalist one. Many of the staff are third generation and he has grown up alongside them.

Draining challenges have arisen when new farms have been bought or leased and a new culture of employees added to the mix. People are generally very untrusting and, for example, it has taken Gary a few years to get the latest recruits to accept that the provident fund provided to the staff is free with no strings attached.

This is Mike the Mechanic, a gentleman who has been around so long he was here to teach Gary how to ride his tricycle! Although Gary now runs a young fleet of tractors, Mike has plenty implement and building maintenance to keep himself busy.

This is Mike the Mechanic, a gentleman who has been around so long he was here to teach Gary how to ride his tricycle! Although Gary now runs a young fleet of tractors, Mike has plenty implement and building maintenance to keep himself busy.

Gary prefers not to have big staff meetings and has come to rely heavily on his two chief farmers (Gary says he’s much more of a business person now and that the supervisors are the only ones who can really call themselves farmers) Gary is adamant that Simphiwe and Funeka could quite easily run the farms without him. Funeka was Bennidale’s top cane cutter. Yes, a WOMAN was this farm’s most productive cutter. That deserves a round of applause!

Here is another lady cutter I found harvesting. So, for all those farmers out there who thought woman weren’t strong enough …

Here is another lady cutter I found harvesting. So, for all those farmers out there who thought woman weren’t strong enough …

Harvesting: First off, Gary does not use any ripeners. He’s had a couple of bad experiences where ripeners actually resulted in decreased RV and is now understandably dubious of trying again. He may have to reconsider his stance with some of the new varieties but it’ll be with some trepidation.

Another thing he’s tried and proven unsuccessful is trashing. The excessive trash accumulated in the longer growing cycle coupled with the lower temperatures means that cane simply doesn’t germinate. Besides that, a trash blanket would just provide fuel for the prolific fires that plague 25% of the farm. He looks forward to the day that we have a self-trashing variety of cane.

Gary attends every fire personally and ensures that cold-burns are the norm. Harvested cane is placed in windrows and a Bell loader places it into a box trailer for transportation to the loading zone. The longest haul is about 1,5kms. From the zone, a contractor transports loads 50kms to the mill.

1 Every year, KwaShukela comes and gives cutters a 2-day refresher course on harvesting. I questioned the need for this every year but Gary insists that productivity and accuracy never fails to show improvement after the course, each and every year, thereby justifying the cost.

Every year, KwaShukela comes and gives cutters a 2-day refresher course on harvesting. I questioned the need for this every year but Gary insists that productivity and accuracy never fails to show improvement after the course, each and every year, thereby justifying the cost.

Administration: Although Gary’s Dad left him to run the farm from day one, his mom remained involved in the office, for which he is very grateful, as admin is a chore for him. But he’s had to get his head around it as up to 40% of his time is now office-based. He is very involved in industry structures so meeting preparation and report writing consume much of his day. There are benefits to this industry engagement though; he gains an insider understanding into mill operations and perspectives as well as industry complications, all of which is empowering and valuable. He also challenges his own personal tendency to avoid public speaking. “Everyone has to give back at some stage; I’m doing my bit while I can.”

Looking ahead: You know that satisfied feeling you get when the puzzle piece fits snuggly and you know you’re not just hoping it’s right? That’s how Gary fits into his world – it’s a perfect match. But, like I said at the beginning, it’s not perfect because there are no failings or trials, it’s perfect because Gary has decided it is. His attitude has taken it from average to flawless. No, he’s not delusional or in denial, he has simply chosen to be happy. If we learn anything from this story, it’s that that simple choice is available to all of us.

Gary wraps up my visit by emphasising the importance of being a passionate farmer. It is the single-most important characteristic of a successful farmer. A farmer with passion will make a plan, one without it is doomed, particularly in the prevailing financial conditions.

Gary even managed to make me feel better about the time SugarBytes consumed by saying that this review of his operation gave him a chance to assess where he’s at.

Gary even managed to make me feel better about the time SugarBytes consumed by saying that this review of his operation gave him a chance to assess where he’s at.

So, I thank you, Gary, for a mutually beneficial encounter; one I am sure SugarBytes readers will benefit more from, but thank you for making me feel welcome and sharing so graciously.