As convenient as it is, having most of the sugar cane industry based more or less on my doorstep, I do you all a grave injustice by limiting coverage to KwaZulu-Natal alone. Mpumalanga is also home to our most productive farms and therefore invaluable in terms of learning opportunities. The Komati farmers have only recently started receiving the SugarBytes articles (I grow the readership as the various mill group areas are willing to come onboard) and therefore a little unsure of this KZN-meisie wanting to interview them. Having managed to convince three of them that I was fairly harmless, I began preparations to trek north.

Google informed me that it was an 8h45m trip, via Ladysmith, Newcastle, Volksrust, Ermelo, Carolina and Barberton so I set off early in my 1.2 Hyundai (my Ford Ranger had been stolen two weeks before and was still in panel-beating, recovering from its ordeal on the wrong side of SA law).

It was only when I got to Mpumalanga that I learnt there was a shortcut through Swaziland … what can I say, navigation is not one of my strengths.

En route

En route

Once there, I could immediately see why so many choose to make this their home. It is spectacularly beautiful “Jock of the Bushveld” country. Being winter, it’s very dry but there was a rugged charm, even in that.

Unless you find a lucrative market for thorns, anything else that grows here requires irrigation but, once that’s operating, the heat creates a tropical climate favoured by many crops including citrus, paw paws, bananas, mangoes, litchis, avos, veggies, sugarcane and macadamia nuts.

Notice the level of security around the macs … something to consider when diversifying?

Notice the level of security around the macs … something to consider when diversifying?

The 2015/6 drought was acute up here. The severe lack of water meant that farmers had to choose which crops to sacrifice. As cane is relatively less expensive to plant and requires more water than trees to thrive, many cane fields were foregone, in favour of saving the fruit trees. This means, now that the drought has broken, many farmers are now catching up and replanting fallow fields.

The choice here is not whether to irrigate, it’s how to irrigate.

The choice here is not whether to irrigate, it’s how to irrigate.

Another interesting point I learnt about this area is how progressive their transformation has been; 80% of the land under cane is black-owned. That has happened through the now familiar land claims process as well as active redistribution by RCL, who owns both Mpumalanga mills and the Pongola mill. As they were the largest land owners, their transformation programme accounts for most of the redistribution.

Coming in to roost, I decided to make Hectorspruit my home for the week, putting me half way between Komati and Malelane. The first farmer I will present to you feeds the Malelane mill.

| Date interviewed | 26 July 2018 |

| Date newsletter posted | 10 August 2018 |

| Farmer | Mike Lurie |

| Farm | Rowan Tree cc |

| Mill | Malelane (8kms away) |

| Area under cane | 160 hectares |

| Production | 18 to 20 000 tonnes per year |

| Other crops | Sunflowers and seed maize for Pannar (rest crops) |

| Cutting cycle | 12 months |

| Av Yield | 125 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 13.8% |

| Best Yield | 190 tonnes per hectare (plant cane, after a veg crop) |

| Best RV | 17% (N40) |

| Varieties | N36, N40, N49 |

I need to start off with a heartfelt thank you to Mike for being such a pleasure to interview; from the first contact, he was open and welcoming. That’s not always the case in my world, so I am especially grateful.

Mike is fairly new to the area and quick to try and refer me to farmers he felt were far more successful. He has been in farming all his life, in many different parts of the country, and it was wonderful to hear his interesting views on agriculture. We discussed the ebbs and flows of various crops and how nothing goes up forever; it is with this view that we considered the popularity of macadamias in the area. He’s seen the cycle applied to many crops including citrus, which is currently coming back into vogue after a mass plough out a few years ago.

Mike combines farming with property development and chose his current farming location with that in mind. A hospital and retirement village are planned on part of the property as soon as the red tape obstacle course is traversed. This particular valley, for some reason Mike can’t explain, is plagued by strong winds – this limits the crops that can be grown here, despite it having the same tropical climate as the areas around it.

The most interesting part of my discussion with Mike was around fertilisers and how much is enough. We all know that the main stream method of deciding how much, and which, fertiliser to apply is by submitting a soil sample to SASRI. When you do that, you state what your desired outcomes are; ie: 100 tonnes/hectare, (My ‘colour-outside-the-lines’ personality has always wondered why no one puts 500 tonnes/hectare )

The recommendations you receive will be in line with the target you submit. So, what happens when you want to push boundaries and apply more fertiliser? Logic tells me that the yields will increase, to a point … but where’s that point? i.e.: how much is too much? As long as the income realised from the additional yield is greater than the cost of the additional fertiliser, shouldn’t you keep going? Mike’s quest began when he saw that wherever the fertiliser applicators paused (and released additional fertiliser in a spot) the cane there was much bigger – since then, he’s been keen to find that point of diminishing returns. This peaked my interest and I began a little quest of my own …

I contacted a couple of the major players in the fertiliser game and was grateful for the feedback from Prof L van Rensberg at Profert. He explained that this is not a simple question to answer. Of course, I wasn’t going to leave it there and pressed for more. Here is the clarity I have managed to find:

- If you’re farming for the short term it is possible to take previous production data (what that field produced in the last season) and the input data (soil sample showing what the soil has in stock) and produce a cost benefit analysis which shows how much additional fertiliser will produce additional yield – and on that analysis, there will be a point of diminishing returns.

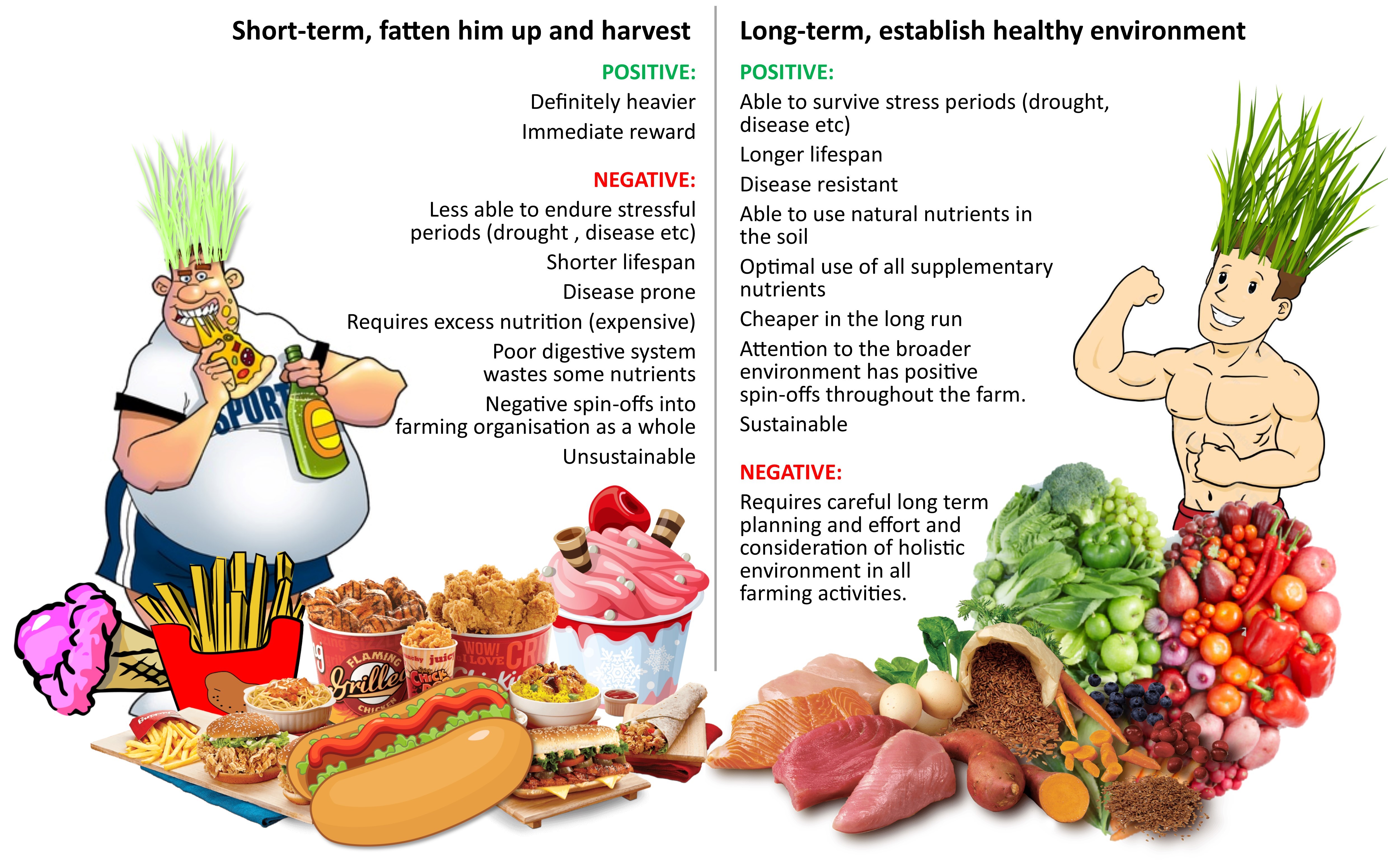

- If you’re farming for the long term, the answer is not nearly as neat. Primarily because SOIL HEALTH is a long-term investment that is vital to building optimal yields over time and is highly susceptible to many factors, a major one being fertilisers. In an effort to simplify this concept for myself, I created this parallel to human health:

To translate this into the context of farming sugarcane:

- A soil’s digestive system is important. To function, it needs to be alive and full of the right organisms.

- The bio-availability of elements is determined by soil health (bacteria and fungi colonies) and water.

- Instead of feeding MORE, we need to focus on feeding RIGHT. Ie: ensure that what is applied can be used efficiently by the crop in the ground and not adversely affect the following harvests.

- Rather than focus on applying MORE fertilisers, focus on soil vitality which, when in a healthy state, can require LESS fertilisers and still result in BETTER outcomes.

- Applying too much fertiliser can create a toxic environment. The unwanted / unavailable elements build up to toxic levels and create environments that are difficult to correct.

I was intrigued to learn that soil not only has a digestive system, but it also has a memory!! The plants that grow in the soil generate this memory when they give off chemicals that feed the soil microbiology. These chemicals vary depending on stress and growing conditions experienced by the plant. So, the soil microbiology, upon receiving information from the plant (in the form of chemicals), adjusts itself to the current situation. When a crop is harvested and a new one grows, the soil memory affects that new crop.

So, there we have it: an explanation as to why more is not always best but each situation is unique and requires a study of:

- what you want to achieve, (Goals)

- when you want to achieve it, (Time frame)

- for how long you want to keep achieving, (sustainability)

- in what environment, (current situation)

- with what investment, (available resources – time, money and energy)

- and priorities (the footprint you leave on the earth)

Once you’ve made those decisions, the best way forward for YOUR farm will be clear. And there are so many specialists available to assist. Richard Cole is a farmer who prioritises soil health and, if you’re interested, you should have a look at his situation.

Neil Miles from SASRI, also responded to my plea to understand this situation and his response was both incredibly helpful and simply put:

- The first consideration that I would like to draw your attention to is that SASRI has over the last 70 to 80 years run in excess of a hundred nutrient (fertiliser) response field trials throughout the SA sugar industry and Swaziland. The cost of running these trials would no doubt in current terms amount to hundreds of millions of rands. Soil scientists, agronomists and statisticians design and run such trials, and go to great pains to ensure that results are interpreted correctly and are used to underpin recommendations for growers.

- Simply put, the purpose of such trials is to reliably establish the point that defines the optimum rate of application of a particular nutrient. Note, though, that the crop is not responding to the ‘fertiliser’, but to nutrients in the fertiliser. So, for example, urea – one of the most widely used fertilisers – contains only one nutrient, nitrogen. The plot thickens, since the crop takes up 13 nutrients from the soil, and soils differ widely with respect to their reserves of the different nutrients (phosphorus, potassium, calcium, zinc, ……).

- For each of these nutrients there is a response curve defining the nature of the response (tons of cane per kg nutrient applied) and reflecting an optimum value, above which there is no yield response to further additions of the nutrient. Bear in mind, however, that the response curve differs for different climatic areas, soil types, and sometimes for different varieties…… All this information is built into SASRI’s Fertiliser Advisory Service recommendations system, and so each time a grower sends a soil sample to FAS, he benefits from this body of research data. The important point is that the ‘turning point’ or ‘optimum’ for each nutrient is not determined willy-nilly but involves no small amount of research!

- A complicating factor in all this is that growth potential often varies widely from season to season due to weather conditions. So, for a nutrient such as nitrogen (N), which is the ‘accelerator pedal’ in sugarcane growth, getting the rate exactly right is a particular challenge. This may explain why your man, Mike, was getting big responses to extra N last season. To deal with this, SASRI is advising growers very strongly to make use of ‘N monitor plots’ or ‘strips’ in order to fine-tune their N applications. All that this involves is applying extra N over and above the normal application to a small part of the field, and then observing growth differences between the monitor area and the remainder of the field. When the latter lags behind the monitor area, more N must be applied to the field as soon as possible. Simple, yet highly effective.

- The yield target (‘desired outcome’, as you put it) listed with the soil sample submitted to FAS is based on findings from the multiple field trials in the different areas, as well as on grower and extension specialist experience. Yes, you can list 500 t/ha, but neither SASRI or our recommendations for fertiliser will get you there….!!! Factors defining the yield (agronomic) potential on a particular farm include heat units, sunlight, water supply, soil depth, crop nutrition, pest and disease management, …. Note that several of these factors (climate, soil depth, …) are uncontrollable. Management is of course, a huge factor in the equation; scientists have identified 40 or more controllable factors that impact yields (e.g, weeds, diseases, pests, nutrition, soil compaction, ….), and management of these numerous factors has a major influence on attainable yields.

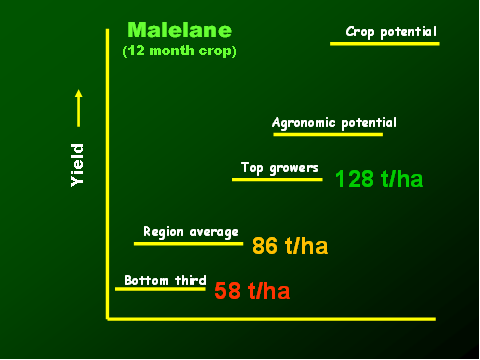

- Some years ago, I did an exercise which involved looking at yields in various parts of the sugar industry. The chart below includes the Malelane data from that study. What is meant by the ‘agronomic potential’ for the area is the yield that could be achieved under those climatic and soil conditions if all controllable growth factors were absolutely optimized. My guess is that for Malelane, the agronomic potential is somewhere between 200 and 250 t/ha. The crop potential is essentially the genetic potential, and it is of not much practical consequence – it is the absolute maximum yield possible if every growth factor (heat units, sunlight, water, rooting nutrition, …) were at the optimum. The challenge for growers and extensionists is to close the gaps between their current yields and agronomic potential yields on their particular fields.

- ‘Closing the yield gap’ is not simply a matter of adding more fertiliser, but of addressing the many factors involved in the growth of the crop.

- If the grower applies too little nutrient, yield losses are incurred. It is of the utmost importance that this does not happen since sugarcane is a highly efficient crop in terms of utilizing nutrients, so the returns on fertilisers are very, very favourable. And one does not need complicated economic models to substantiate this!

- Too much nutrient (going ‘over the top’ of the response curve), on the other hand, is also not smart farming. In the first place it is wasteful expenditure – impacting the bottom line, secondly, it often results in a decrease in sucrose levels in the crop, thirdly, it increases susceptibility of the crop to pests and diseases, and fourthly, it can result in pollution of streams and dams.

Thank you, Neil, for that valuable explanation – of particular value for our farmers was the part about a ‘N monitor strip’ – I hope many farmers who aren’t doing this, realise the easy gains to be reaped here.

And, after that lengthy digression, we get back to Mike’s situation:

Mike explained that many people would disagree with his other current philosophy that nitrogen (N) and potassium (K) should be applied in equal quantities to get the best quality cane. As the soils up here are already rich in phosphorous, he limits that to about 50 kg/hectare when applying 100N & 100K in the planting furrow. In his latest trials, he’s done a second application of another 100:20:100 after planting and then followed that up with a third application of 75:20:75 when the cane is about to canopy. This totals 375:60:375 and has, in the small trials he’s done so far, resulted in yields of 180 to 190 tonnes per hectare. In all the trails he did, as long as the N and K were applied in equal quantities, the RV remained well above the mill average. However due to the aggressive growth of the plants, Mike found one needs to dry off the cane a lot longer; up to 10 weeks.

In his latest trials, he applied the third application, in liquid form, in the middle of 2 rows. So far, for him, there have been no distinguishable benefits of liquid over granular products. He always adds boron, zinc and sulphur as recommended by SASRI. His fertiliser is ordered premixed and applied by the supplier.

And now for a quick whizz around the rest of Mike’s operation:

Compost

Closely linked to fertiliser is compost, which Mike uses when planting. Last year he used seabird guano which is sourced from the West Coast. Suppliers mix it with lime which both supplements and dries the guano out, making it easier to apply. He bought it in 25kg bags for R200 per bag in 2017. This year it has increased to R400/25kg and, although his crops response to last year’s application was excellent, he’s decided that’s just too expensive. This year, he’s reverted to his usual mix of chicken and kraal manure (about 10 tonnes/hectare) placed in the furrow, in addition to the fertiliser.

Field preparation and planting

Mike emphasises that fields need to be cleaned properly before replanting. Kweek (cynodon) is a challenge here and needs to be completely eliminated before planting new cane. He uses a mould board which successfully turns the soil over, which Mike says thereby kills the kweek. After a thorough, deep plough, the field is left to rest. During this time (usually about 6 months), it will be cultivated (ploughed) periodically in order to remove all the unwanted weeds. Then a rotation crop is planted. Once that has been harvested, Mike ploughs again and places both organic (about 10 tonnes/hectare of manure) and chemical (100N, 100K and 50P) fertiliser in the furrows. The seedcane is placed in the furrow, double stick and chopped into billets.

Mike grows his own seedcane, which is tested by P&D.

Lately he has been using a spray to deal with the recent onslaught of worms and unhealthy fungi. After that, he closes with a tractor drawn implement that folds the soil over the furrow and he sometimes uses a small tractor to compact the soil slightly but explains that the irrigation usually deals with air pockets adequately enough.

They then top dress with another 100N, 100K and 30P and spray pre-emergent herbicides.

Rotation crops

These are chosen for their financial returns, rather than any contribution to the soil. Currently Mike has sunflowers and seed maize (for Pannar) in the ground, both of which work well with a “clean up” programme. For Mike, cleaning the field is a major part of resting it from sugarcane so anything he puts in needs to allow him to use RoundUp or another similar herbicide that will help leave the field absolutely clean.

Seed maize for Pannar

Seed maize for Pannar

Other crops we discussed were:

- Cotton – there is a lot of talk of a gin being established in the area. Mike says that although cotton has a relatively long season – 6 months – it is becoming more popular because the maize price is so bad. It is also completely RoundUp ready and bollworm resistant.

- “Tomatoes and green peppers are another option but, we’re a long way from the market and tomatoes, in particular, are basically just water. The tomato industry is also dominated by ZZ2,” says Mike.

Ripening

Mike not only concentrates on maximising yields, he also does whatever it takes to maximise purity. He follows a piggy back ripening programme that sees Ethapon or Etheryl sprayed early in January, followed by Fusilade in February in order to harvest at the end of March. Even cane harvested later in the season, and therefore partly purified by the dry winter weather, is ripened.

Installation of solid set irrigation

Installation of solid set irrigation

Irrigation

Mike prefers a solid set arrangement, after having struggled through drip previously. He explains that the constant blockages make the system unmanageable. When he bought this farm, it had surface drippers; one line every second row. With this configuration, an undetected blockage caused a setback in both the rows it was servicing. To minimise the damage caused by blocked pipes, he added extra lines, having one in every row, but the overall outcome was still negative. The furrow that the irrigation water comes from is full of bacteria and spirogyras (apparently that’s an actual organism) this means that, even if the water is filtered, micro-organisms slip through the filter and grow on the other side – in the pipes – causing blockages that are very difficult to dislodge. Chemicals (eg: Chlorine) designed to kill these organisms often have an adverse effect on the crop and the soil. The solution for Mike was to convert to drag lines (on the land he plans to develop) and solid sets (on the land he will continue farming).

Although he admits that it is not always simple advice to follow, less water, more often is far better than more water, less often. The latter scenario only serves to move the crop from a place of stress (from over-watering) to stress (drying out). His focus on this area has been beneficial to his results.

Pests:

Eldana will infest cane that is carried over so the simple solution is to avoid any carry over. I found that, as this area is very comfortable in the 12 month cycle they practice, Eldana is managed in line with this cycle. Apart from that, there is no real management system we can learn from.

Mike explains that Smut can be a challenge but one that is easily addressed by managing the stress the cane is placed under. Avoid stress and smut seems to abate. New varieties have improved Smut-resistance, which also helps – and is a good reason to keep up with the new releases by SASRI.

Thrips come and go and have, in the past brought Mike to the point of spraying pesticides but, he’s not convinced that the sprays are worth the cost as the little critters do tend to move on before causing significant damage.

Harvesting:

No green cane harvesting on Rowan Tree; everything is burnt.

During the wet season, the harvest will be loaded into trailers with the Bell, to avoid the truck coming into the field and risk getting bogged down. The trailer is taken to the zone where a crane transloads into the truck-trailer. During the dry season, the truck will drive into the field and the Bell will load directly into the truck-trailer.

To address compaction, Mike does ‘cultivate’ the cane after harvesting which entails loosening the soil in between rows before he sprays preemergent herbicides and applies fertiliser.

Reasons for success:

Clearly, this is a successful farming operation and Mike attributes it to:

- Attention to detail.

- Work hard, with no short cuts.

- Having a genuine passion for farming.

- Independence – he does not employ subcontractors for harvesting or transport and prefers the flexibility and independence having his own cutters and truck affords him.

I fully appreciate that Mike is swimming upstream with many of his practices, but aren’t all pioneers and industry leaders? When he says that he’s not happy to settle for anything less than pushing the production limits, who can argue? Debt, determination and passion create a cocktail that will require you to step out of what is tried, tested and comfortable into the space where others prefer to spectate. Who can blame him for wanting to get the most out of his land? We are sincerely grateful for the experience of being on Rowan Tree and for the interesting discussion on fertilising that this stimulated.