Yay! At last it’s time to share this epic JAFF with you again. Yes! We’ve met him before, when we visited him a few years ago, for macadamias. No, you’re not re-reading last month’s story; this is a new one, similar situation though.

I’m so excited about sharing this farmer with you because he is an authentic individual; he marches to the beat of his own drum, is deeply connected with Nature and makes no apologies for the way he farms – because he doesn’t have to – his land will be better after he’s gone than it was before!

Whilst we know that this style of farming is not for everyone, nor is it easy or particularly profitable, there are some distinct advantages for the land AND the farmer. But I’m getting ahead of myself … let’s meet JAFF 10.Avo

A quick warning: this is a two-part story – there was simply too much goodness to risk any of it getting lost with short concentration spans or daily distractions …

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 15 September 2022 |

| Area | Levubu, Limpopo |

| Soils | Huttons – 43% clay |

| Rainfall | 1500 – 1800mm annually average; seldom over 10mm between mid-May to mid-Sept |

| Altitude | About 200m above sea level |

| Distance from the coast | About 850kms as the crow flies |

| Temperature range | 18°C – 37.4°C (July can go to 1°C min) (mid Oct – 42°C max) |

| Wind | Average around 3km/hr |

| Varieties | Maluma, Hass, Fuerte |

| Hectares under avos | 70h (has replaced a lot of old orchards) Made up of:

9ha green skins (Fuertes) 40ha Maluma Hass 21ha Hass (will increase this by another 10 to 15ha) |

| Other crops | Bananas – 33ha (5ha on his own farm), macs – 65h (own macs) plus over 100ha on leased land.

*leased macs are not farmed “JAFF’s way” because he is a partnership in those. |

UNCONVENTIONAL

JAFF kicks off by sharing his views on why most farmers farm the way they do and why he is seen as ‘unconventional’; “The Agricultural Educational Institutions are subsidised by big business so they will promote (by including in the curriculum) the use of those business’ products and methods. There are no schools that will teach youngsters how to farm the way I do. Corporates won’t support it and it’s not a quick fix. Everything you do now will only show results 2 years from now. This is also not a cold turkey solution; if you’re going to adopt it, it will require gradual integration.”

He continues, by explaining that humans like to be in control and that the biggest obstacle to farming with Nature is in peoples’ heads, “People don’t believe that Nature can look after herself and deliver the best commercial results.”

WHERE ARE WE WITH MACADAMIAS?

The last time I was here was in 2020, just weeks before we heard the word Covid for the first time. Like all the Levubu farmers, JAFF was struggling with insects (stink bugs in particular); he’d just come out of a season of devastating loss after he’d tried to hold back on any pesticides. I remember him saying that he was going to have to implement an integrated programme when it came to the macs.

Since then he’s also refined the pruning process and he recapped the learnings (remember that Levubu is where macs were first planted in South Africa – they’ve had to figure out everything themselves); “About 12 years ago, we saw we weren’t getting the results we should and decided to prune (trees were about 17m high). We cut 7m off every second tree, every second row*. This was a mammoth task as there was a LOT of wood on the orchard floor when you prune extensively like this. We did this for 4 years until all the orchards were down to 10m. Of course, by the time we finished, the original trees hadn’t been touched for 4 years! We had to get to a place where every tree could be pruned every year. Since then I’ve learnt that the trees actually require attention twice a year as a summer flush prune is also necessary. Retraining 40-year-old trees is not a simple task!”

*JAFF explains that this was too harsh – the trees went into shock and produced wood rather than nuts. These soils are very nitrogen rich. His latest pruning strategy is to do a substantial prune after harvest; aimed at getting light in but he doesn’t bring the height down too much – the aim is to leave some wood there so that the tree doesn’t feel the need to make more wood. Once the nuts have set, he goes back and takes some of the height down, leaving one taller shoot that is exposed to the chemicals for stink bugs. This is so that the stink bugs think they have immunity in their ‘Embassy’ but actually … they’re wrong. JAFF is keen to see how that affects this next season. [JAFF was happy to report, when proof-reading his story, that Unsound Kernel Recovery was down about 3% – what a win!]

JAFF says that some “free range surfer farmers” (his words 😂) he visited in KZN inspired him to try a more biological approach to stink bug control; a Broad Band product. The result: he had to throw away 20t nuts with stink bug damage and still had a 10-12% unsound rate.

He explains that the trouble lies in the yield; Levubu has many old cultivars which deliver a TKR of 32 to 34%. When you factor the 7 – 8% damage on that, PLUS some other damage, it’s just not viable anymore. [JAFF also reported, in his proof-reading feedback, that the harvest was also up 40% on last year. Perhaps macs in Levubu could still redeem themselves?]

Although the ‘surfer farmers’ get similar unsound rates using a biological approach, their much higher TKRs** (45 – 48%) mean they can afford it.

Bottom line is that JAFF believes, to farm macs with an integrated pest management approach, you need to have a high TKR. He believes farming with a reliance of chemicals is unsustainable. At the moment, yield on macs in Levubu is just too low to be viable.

** New varieties and more suitable climate account for this.

A CHANGE IN FARMING

JAFF points out how much farming has changed in the last 10 years. In his Uncle’s time, everything was cheap (labour, diesel, electricity) and farms were paid for- it didn’t really matter how much you produced, life was good. Nowadays it’s a very different situation, with costs having sky-rocketed, and scale being one way to escape collapse, farmers need to question & examine every input from every angle – precision is the name of the game as farming itself becomes marginal. We run to escape the jaws of rising costs and survive in an ever-narrowing profit margin. Will macadamias in Levubu soon disappear?

Are the avos any better? I wondered nervously … JAFF finds it much harder to farm with macs (in Levubu) – he says that avos tell you when they’re sick. They tell you when they’re happy. Macs just don’t make money here; and “they don’t talk to me!!” says an exasperated JAFF.

AVOS

I’m glad we’re here to learn about avos and JAFF kicks us off by quoting his Uncle; “Plant the best tree you can get your hands on, in the best soils. It’s not easy to keep an avo tree healthy so you have to start off with THE BEST.”

What is the best avo tree?

JAFF explains that that is different for every farm. Here, his best orchard is a 41-year-old Hass orchard on Edranol seeds. “But,” JAFF qualifies, “it was planted into virgin soils. This always allows you to ‘get away with murder’”. Everything here, over 15 years old, is on Edronal seeds with only a few Duke 7s being the exception.

JAFF also explains that all the orchards seem to have a similar pattern of half the orchard being nice and the other half being a bit ‘second rate’ – this is because his Uncle had his own nursery and he’d go in there to select his best trees to plant. As he progressed through the planting, the ‘best’ trees got progressively worse leaving the 2nd part of the orchard positively second-rate.

To make sure he doesn’t repeat this pattern, JAFF only buys the trees in from professional, independent nurseries rather than trying to grow them himself.

SEEDLINGS VS CLONALS

“You have to buy the BEST; a good clonal costs about R300 per tree opposed to a seed-grafted tree at R100 each. There’s absolutely no sense in buying anything less than the best, especially when the difference is only R200 for a tree that will produce for the next 40+ years.”

Seedlings will always have inconsistencies and this affects the management of your orchard down the line. “Clonals make sense and are worth the investment,” advises JAFF and then uses this analogy, “You can’t get a good steak from weak cattle.”

PLANTING

Roots are where JAFF focuses during planting; he takes a lot of pictures, especially if he’s concerned about what’s come in from the nursery.

As far as making sure your new trees are “the best” JAFF recounts a similar checklist to what we’ve heard before;

- healthy roots,

- strong, smooth graft point,

- stem that isn’t too thick or too thin,

- not too long,

- flush must be hardened off

- with some nice strong leaves.

JAFF says you should also check that the cultivar delivered is what you ordered – this is a big problem with nurseries at the moment; especially with macs.

JAFF also tests new avo trees for sunblotch as soon as they come onto the farm, before he plants. I love how he positions this; “The beginning is such a lekker chance to get everything right – don’t waste it!” Test test test BEFORE YOU PLANT. It might seem extreme but … you only get ONE chance to start. Anything after this is a fix, not another start. Testing is expensive so JAFF suggests that you split the batch of trees that come in – number them, keep accurate records and send samples from each batch for testing – if the tests pick up anything, go from there to establish the extent of the problem. Sunblotch is not always visible as JAFF found out when he had an issue with it in one of his orchards – the only symptom was low yield and only after they had exhausted EVERY other possible cause did they try testing for sunblotch and it came back positive.

The next 40 years is worth a little bit of testing and caution in the beginning.

What is the best soil?

This comes down to matching the root stock to the soil and the weather. Eg: Bounty is good on clay soils in Levubu where there is a LOT of summer rainfall. It’s a little more resistant to phytophthora. There are some other new root stocks coming through but they still have to prove themselves. And here, JAFF is talking about long-term proof; some trees can be be brilliant for 10 years then suddenly dip; maybe they recover, maybe they don’t but you need to know if the root stock can go the distance before you invest in it. To hedge against this risk JAFF advises that you never put all your eggs in one basket; always mix it up both for the root stock and the bearing wood. You never know what the future holds and the best way to mitigate your risk is to spread it. Besides this, stay informed on the markets and also trust your intuition and be sensitive to what you like to farm. “Avos are not avos; they are all very different,” says JAFF cryptically.

The soils here are about 43% clay content which is a bit high for avos as it retains moisture. Ever the optimist, JAFF adds, “this helps though, if you don’t have rain for a while.”

CULTIVARS

MALUMA

This cultivar is named after this farm where it was first grown. JAFF’s uncle found a couple trees, in the Hass orchards, that were producing bigger fruit than the others. He would pack them in with the Hass but then decided to explore and trial by grafting this material into more of the orchards. Eventually he created a whole orchard – which is still here today. JAFF says, “To this day it is the best orchard, of all the farms we are farming, in terms of tonnes per hectare.” It’s a small orchard; only 0,6 of a hectare. It’s on edranol seeds. It is 38 years old and yields 16 tonnes per hectare. Across all JAFF’s farms his average yield is 8,9t/ha.

Besides Maluma Hass, JAFF also has normal Hass and Fuerte. Here’s a few handy pointers on the differences between these three cultivars:

| Maluma Hass | Hass | Fuerte | |

| Fruit | Larger, dark skinned | Smaller, dark skinned | Green skin |

| Leaves | Long leaves | Bigger, Round shaped leaves | Big leaf |

| Growth patters | Smaller trees that tend to grow upwards | Prone to shooting inside the canopy and making it full and dark | Growth pattern is more ‘walking’ ie: branches grow down and then swoop up. Uncle always said like a hen and kuikens. |

| Peculiarities | Very difficult to forecast – you have to get into the orchards and look into the trees – they hide their fruit | Prone to sunburn | |

| JAFFs spacing | 7m x 4,5m | 8m x 6m | 8m x 6m |

Big leaves, characteristic of a Maluma

JAFF is happy with the shape on this mature Hass tree.

A young Fuerte

BENCHMARKING

The Levubu farmers use their data to generate benchmarks. JAFF explains how important this is; “It helps you identify when a field is no longer profitable and you can investigate possible remedies and, if you are doing it alongside your neighbouring farmers, you will be able to establish whether the ‘markers’ are unique to your farm or common across the area; further equipping you to isolate possible causes; both good and bad.”

Sometimes this benchmarking is just ‘interesting’ eg: JAFF can see how much fertiliser costs his compatriots – and they can see how much pest damage he has. JAFF says; “I find it interesting that, in terms of yield, we are all in the same bracket and yet I am not using any chemical fertilisers.” It’s also been very helpful in terms of figuring out what’s going on in Levubu with macs right now. “Knowing that we are ALL producing low yields means that it’s not a management issue so we can stop looking for the cause in individual farm-related places.”

Yes – you read that right – JAFF uses absolutely no chemical fertilisers! That doesn’t mean he doesn’t nourish his crops; quite the contrary – most of his efforts go into supporting the soil which, in turns, feeds his trees.

COMPOST

JAFF has a full-time kitchen running to feed the host of soil noonoos he keeps safe on this farm. Chef’s favourite is mature compost and the ingredients are cattle manure, sawdust, nut husks and shells, activated biochar and some Grow-Agra (essential micro-organisms). It is prepared in the open and turned and watered as required. It is delivered into a 100-litre pit (or two) that he drills next to each tree as often as he can (which ends up being about every 3 years).

Compost mixed today that will now sit and wait for the rain. If necessary, JAFF will fill the JACTO with water and Grow-Agra to add moisture.

JAFF takes a handful from the compost pile and explains the recipe … pine sawdust, cattle manure, activated carbon, mac husks, mac chips (of cuttings).

He then goes on to say that you can gauge a compost piles’ health and readiness by the amount of Mycorrhizae (white strings) present.

In this video you can see how the auger drills a 100l hole next to the tree. JAFF then fills this with compost.

Here we see that compost has been placed next to the tree. While JAFF was replacing his auger, he continued placing the compost but had to leave it above ground.

A handful of avo roots that have grown into the compost pile. JAFF explains that this is fine except that the compost doesn’t last; “It gets eaten up and then the roots are left above ground,” he explains and that’s why he prefers to drill the pits and put the compost where the roots are safe.

JAFF’s excitement is infectious as he drops to his knees in one of the orchards and digs into a compost pit he’s recently filled alongside a 2 year old tree. On the left you can see evidence of the biochar. On the right you can see fresh white roots accessing the pit – it makes JAFF very happy to see that the avos are enjoying his compost! “You know they’re avo roots because they’re very soft,” he explains.” It really was remarkable how extensively the roots of these two-year-old avos were infiltrating this pit!

JAFF says, “You don’t have to do all sorts of funny courses on making compost. Just mix your compost, give it enough water, add an activator in (Essential Micro-organisms) and then wait for it to go dark.”

He then shares another pearl; “You know how the old Afrikaans ladies had a ‘suurtjie’ (potato in a glass bottle) from which they extracted yeast to make their bread rise?” No JAFF, I’m afraid I am unfamiliar with that “Well, I do a similar thing!” What JAFF is referring to is leaving about 1/5 of the fully mature compost to kick-start the next batch. “That’s my ‘yeast’ that starts the party!” he clarifies!

It was at this point that I recognised a ‘golden thread’ that runs through this entire operation; DON’T TAKE EVERYTHING. By implication that means leaving something … for Nature, for tomorrow, for balance. This principle even applies to the people! JAFF and I were discussing cultural peculiarities and he praised the Vendas as a wonderful group; paying particular reverence to the old Venda ladies. He has a few in his team and, although they are a little past their physical peak, he keeps them on as the ‘glue that allows him to keep farming’. There’s something very important about having the older generation in the mix rather than an exclusively youthful workforce. JAFF did not realise that he had this ‘strategy’, of keeping elements of his farm, regardless of their monetary/financial contribution until we discussed it. He just looked at me and shrugged, “Some things just have value that can’t be measured.”

And then we were back scratching in the soil … “This is a PROPER avo root that can take calcium up into the system,” explains JAFF. He adds, “That’s what all the clever guys say; it’s not my theory.”

He goes on to build a picture of how the compost builds a mega-environment for the organisms with play-parks and restaurants and swimming pools – “you’re making somewhere they won’t want to leave,” he laughs. It also lasts longer than anything else. The recommendation of Dr Cloete (the man who inspired his uncle to farm with Nature) was to top up with compost every 7 years. JAFF does it every 3 to 4 years.

If there’s only one thing you take aways from JAFF’s story, composting is it!

INSURANCE

JAFF explains why he sees his big compost holes as an insurance … it keeps moisture so, when it’s really warm and you can’t get there with irrigation in time, there’s a ‘reservoir’ and, when there’s too much rain, this pit of compost will also have a lot of air. That’s the great thing about compost; it has a lot of moisture but it also has a lot of air (oxygen); two things the trees need. The roots grow into these pits because they need these resources as well as all the nutrition generated. JAFF says that these pits allow him to get away with being an average farmer. “I might look like a good farmer but, actually, it’s all Nature,” he smiles.

RIDGING

JAFF advocates ridging and has even done some ‘after the fact’ ridging that he says is now very popular among the farmers. “The best tool to ridge with is an excavator,” he says, “I use my TLB to build new ridges but a bulldozer is easier when you are ridging an existing orchard.” He warns that bulldozers are cheaper than excavators and he’s used both in new orchards – he’s convinced that the excavated orchards are doing better. He believes the reason is because bulldozers roll layers of soil on top of each other rather than creating the nice mixed up, loosened soil that an excavator drops.

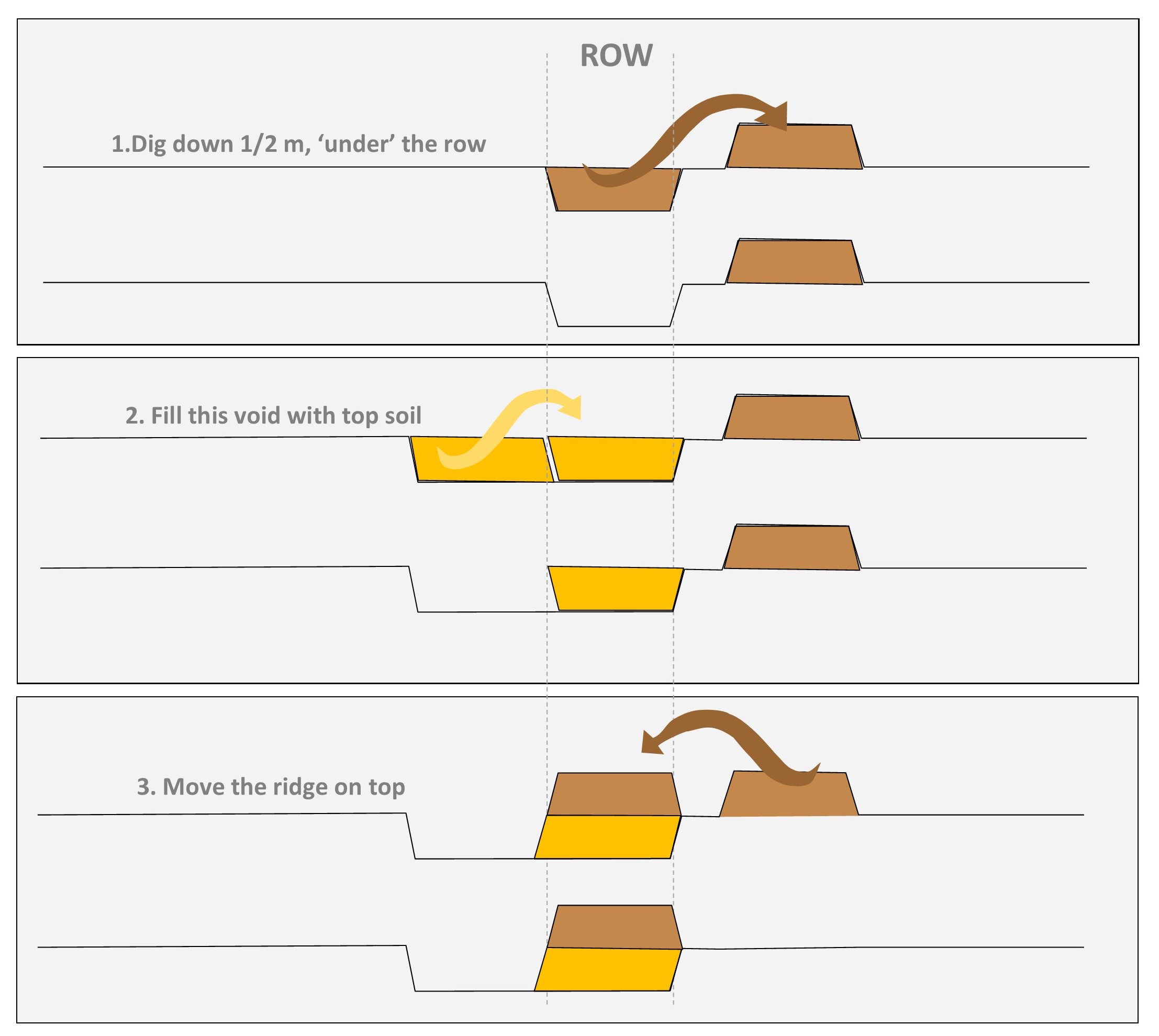

To prep new ridges JAFF digs about half a metre below the ridge and then fills that void up with top soil. He then moves the first ‘excavation’ back on top so there’s almost 1m of loose, surface soil in the ridge. This settles to about half a metre. And the ridges are 3.1m wide.

JAFF tries to get new growth onto the ridges straight after building them. He does this with a cover crop mix. When I ask what he explains that there’s so much on the market, “Just make sure you have variety; some flowers, height variations, some annuals, some perennials. It doesn’t really matter as long as you get the ridge green again because red is not good – everything burns (the life, the carbon etc) without a covering.”

Ultimately indigenous vegetation is going to take over regardless of what you plant. And if you, like him, are reluctant to use glysophate, then there’s no way to get rid of them so, work with them! “Cut it down when it needs to be cut but don’t waste money sewing seeds of plants that won’t last,” is JAFF’s advice.

Newly prepared ridges for hass avos – 9m x 7m spacing. The soil will still be disced and a cover crop planted before leaving the soil to settle and the green to grow. Smaller spacing, like 7m, would result in a smaller ridge (about 2,2m) but he’s created this one bigger to align with the old orchard at the far side.

JAFF also explains that ‘after the fact’ ridging has improved the tree health substantially (read this story https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/jaff-31_part-2/ for an explanation of this) BUT, when the soil was disturbed, the star-grass took hold and he’s now struggling to get a handle on that. JAFF says it’s quite common that farmers are ridging previously unridged orchards this way and it’s simple; you just rip the interrow and then send the bulldozer through, scraping one side and then back again, pushing to the other side.

This Maluma orchard was planted in 2012. It is spaced at 8m x 6m. It has been “crinkle cut” (see info under Pruning) and was ridged ‘after the fact’ a few years ago. Last season it produced over 16t/ha.

JAFF planted wheat (hawe) on some new ridges. He smells the earth and says he wishes he could WhatsApp or email the smell of his soils.

SPACING

JAFF explains that Malumas grow differently to Hass and Fuerte – so these are planted at 7m x 4,5m. Hass and Fuerte he plants at 8m x 6m. All his older orchards are 9m x 7m.

JAFF is starting a high-density trial with these 13-year-old Malumas. The original orchard was planted at 9x6m and it yields only 8t/h. Because JAFF prefers his trees small, he’s optimistic about increasing the density (and yield) without any adversity by adding another row in.

MORE ON PLANTING

A mix of carbon (bio-char) and Grow-Agra (essential micro-organisms) is prepared in a 20 litre bucket. He adds a coffee cup amount of this in the base of the hole he’s prepared in the ridge. JAFF warns that you need to be very careful when planting into fresh ridges because they can suck the tree down … “it’s like a freshly dug grave,” he says, “so plant 1/3 of your root soil above ground and cover up to the top of the bag height so that, when the ground sucks the plant in, it will come level with the ground.” After about 3-6 months, he then digs a big hole with the bobcat auger next to the tree and fills that with compost. After another 9-12 months he’ll do another hole, with another 100 litres of compost, on the other side, and then he leaves it for 4 years.

“All you need to do then is keep the ster-gras away,” he groans. When the tree starts bearing he’ll fill 2 new holes, each with another 100 litres compost, every 3 years.

JAFF reminds me that his way is not like a fertiliser programme where he has to apply in “March” so that it syncs with leaf flush etc etc … this method of nutrition runs on Nature’s schedule.

In terms of timing, JAFF advises that you plant when your trees are ready but, if you can plan it, he prefers the rainy season. Here, that’s the end of Nov when they’ve had about 120mm rain and there’ll be rain through to Feb.

The only stems painted with PVA on this farm are those fresh out of the nursery; these get a 50-50 PVA-water wash to protect the soft wood.

STAKING

“Yes, sometimes you have to,” says JAFF, “especially with the windy season and some of the enthusiastic little growers can become a bit head-heavy for their young/weaker stems.” JAFF does prune the new trees for the first time in about year 2.

HERBICIDES

Obviously poisons of any kind go against JAFF’s principles so I was interested to pick up on the ‘ster-gras’ he mentioned under PLANTING, both in terms of control and what he thinks about other roots ‘stealing nutrients’ from the root zone area around the base of the trees. He gave a big sigh and said, “You know, that grass! It was planted in this area for cattle. It’s very aggressive and gives off something (chemical) that inhibits the growth of other vegetation. This is a bad one.” Although he hates having to, he does spot spray ster gras.

Here’s a picture of JAFF’s second most hated nemesis, “Bliksem se star gras”. The first is load-shedding.

But, as far as everything else goes, JAFF says, “God didn’t make mistakes. We made (and continue to make) mistakes. We kill everything because ‘it’s eating the avo trees food’. But it’s not – it’s a symbiosis; the plants work together to provide for each other’s shortfalls.” JAFF goes on to explain that, when you remove everything from the orchard all that’s left to feed the avo tree is your irrigation pump and your fertiliser company. And both cost a fortune! JAFF has chosen instead to partner with Nature. He says this partner never asks for money; they don’t have a fancy car to pay for and they’re never on leave! “Same as the bees,” he laughs, “they work for free and don’t take weekends off.”

Seriously though, he warns that the more glyphosate you put down, the more fertiliser you’ll have to put down and it’ll never end. JAFF says the situation reminds him of Macbeth; “When you start, you can’t stop.”

I then told JAFF about a farmer I once met who believed that one of his trees was sick because of the extensive growth under the tree; and that this was depriving the tree of nutrients. At the time, I had thought that the growth under the sick tree was more than the trees around it because the (sick) tree had fewer leaves so more sunlight was getting to the undergrowth but JAFF adds another thought: he says the plants were growing to fix the soil. If the farmer had sprayed them, a stronger set of weeds would just replace them and the result would eventually be a changed, unhealthy soil incapable of feeding the tree and you would need to use chemicals to prevent the tree from dying.

I complained that the back jacks were a pain but JAFF defended (even) those; “But the bees LOVE the flowers hey!”

JAFF goes on to explain how Nature will always defend itself and it’s only through money that we will manage to resist … he raises the example of over-grazed cattle-lands that, once the grasses are all gone, will start to grow other plants, like sekelbos, that cattle can’t eat – why? So the cattle stay away and the soil gets a chance to regenerate. It’s Nature’s defense and, when the soil was healed, the grasses would come back. If we try to work against Nature, or rush her, she will work against you. “Nature’s way takes time,” says JAFF, “but it is the only way.”

ORCHARD MAINTENANCE

With no (minimal) herbicides and healthy soil you can imagine the rampant growth in these orchards. There’s constant brush-cutting and pruning. “But Mark’s clippers have changed a lot for me … 2 guys used his clippers to prune 14000 Malumas, all the Hass and all the Fuertes. I only had to change a motor and blades!” JAFF passionately endorses the Pruiger range of clippers that are imported and marketed by one of our previous JAFFs. “They’re 1/3 of the cost of his competitors,” adds JAFF.

JAFF also uses battery powered pole pruners. And a side mulcher that goes ahead of the pole pruners. “With no break downs you can do about 8 hectares of avo orchards in a day with the side-mulcher,” says JAFF, “and that picks production, of the brush cutters, up from 100 trees per guy per day to almost 200 trees per guy per day”. JAFF always leaves a bit, uncut, between the trees in the rows so that there’s a decent habitat for all the insect life.

Ladies operate the brushcutters – JAFF says the machines last longer with women operators .

The side mower has just been through this orchard. You can see how the natural growth between the trees in the row and between the rows is left and only the immediate area around the micro-sprinkler and on the sides of the ridges is kept down. Once a year, everything is cut back. All cuttings are left in place to break down and enrich the soil life.

Here we see JAFF removing a shoot from the Bounty root stock which he explains is very aggressive – “you really need to watch the shoots off the roots stock; before you know it, it can overtake the bearing tree wood,” he shares.

Here you can see how the ladies are clearing around the tree but leaving a patch in between the trees in the row. Remember one of the primary reasons he cuts is to open up for the irrigation.

EVERYTHING HAS A COST

JAFF understands that his way of farming may seem expensive to others and it is expensive … like when the brush cutters keep cutting the irrigation pipes as they clear the space around the micros. He tried painting every single peg bright orange to help with visibility but that turned out to be a very expensive way to learn that it didn’t work.

BUT everything has a cost – you just have to choose yours … “For me, soil health is worth the mechanical costs and I’d rather return all that vegetative growth into the soil than poison it.” JAFF just can’t farm ‘red and dead’ … if it’s 35°C in Levubu and you put your hand on that red ridge, it’s cooking! “You don’t have to be clever to figure out that you should have green growth to protect that,” says JAFF, “Imagine how little chance the sensitive life in that ridge has of surviving if you don’t!”

And it’s here that we’ll take a break. I know it’s hard but the end of December will be here before you know it and you’ll have the very best read whilst putting your feet up for a moment. In Part 2 we’ll cover:

Pruning (it’s an extensive and intensive study)

Irrigation

Disease

Stress signals

Harvesting & Marketing

Pollination

Insects (a LOT of them)

Pests & Theft