Whoop whoop! It’s time for Part Two of the highly popular AVOS101 paper. If you missed Part One, it’s always available https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2023-01-avos-101-part1/ – be sure to read it before diving in to Part Two …

LAND PREP

Is it just me or does this part of the process make you sigh too? We all know how important it is and how we only get one chance to get it right … nothing new when it comes to avos except that it’s REALLY important that you get it right because they are such ninnies when it comes to their roots and associated diseases. Like Jaff 27 said; “Macs are like weeds, they’ll grow anywhere. Avos are like turkeys … you never know if they’ll make it to Christmas!”

Bram’s top 5 essentials in avo orchard land prep:

- Know your soils.

- Classification (structure in terms of sand, clay and organic matter) This will determine what preparation you do ie: deep rip / ridge etc. (Also what cultivars you plant, how you irrigate and supplement … it’s VITAL information)

- Composition (pH, mineral content, shortages etc) This will determine what corrections you make before planting.

- To save costs apply phosphate in ridge area only and build the ridge on top of that. Phosphate is used by the tree for root development and energy. It does not move easily through the soil profile, making placement critical. If it is deep down in the beginning the mature roots will start to actively take it up exactly when they need it. Add a little bit in planting hole as well so that you have both early growth and mature development covered. (NB: avos are dissimilar to macs in that they are not good miners of phosphates.)

Bram’s preference is for ridging because, although the trees can survive in a flat orchard if the soil is deep and drains well, they just do better on a ridge.

- Prepare drainage.

Bram advises that, regardless of the amount of topsoil you have, deep rip, in the row, before building ridges, so that water is able to drain away through the subsoil.

- Don’t use equipment that will compact the soil.

Bram’s preferred weapon is an excavator or back-actor (TLB) as these both leave the ridges really loose although he says that ‘dozers are also an option as they push the soil up from the sides. Graders are not ideal.

- Only use top soil to create ridges.

Don’t incorporate any subsoil in the ridge. The purpose of a ridge is to create more volume of SUITABLE soil because the subsoil is unsuitable so to then put subsoil on top is defeating the purpose. Therefore, the amount of top soil you have will dictate the size of your ridge. Is the top soil layer easy to see? Bram answers; “No, that’s why professionals are necessary (the ones who analysed the soil classification and composition); they can tell you how deep your top soil layer is. It is imperative that this information is communicated to the land prep contractors and that it is monitored throughout the land prep phase.

- Cover and rest.

After soil prep is complete, throw seeds for a cover crop and let the land rest for at least 6 months. This time is very important to establish a beneficial cover crop and allow the soil life to recover.

Cover Crops & Biodiversity

Bram would like to see more indigenous cover crops, suitable for specific climates, that might address pest issues as well as enhance the soil profile. He thinks there are too many imported cover crops (exotics) being used. Perhaps something that has fodder value, either to graze animals in the orchards or to cut and bale. Clovers, radishes, mustards are all imported. In the Cape, mustards are starting to move into the natural areas and becoming a problem. Farmers should cut before the seeds become viable.

In most avo orchards, farmers are just growing whatever comes up naturally and, most often, that’s black jacks which is a pioneer crop (also exotic) and frustrations with this often lead to the glyphosate being whipped out. Bram suggests that by planting well-considered cover crops straight after land prep, the black-jack war might be minimised.

Good cover crops can provide a refuge for friendly insects, an alternative food source for unfriendly insects, as well aeration, nutrition and shade for the soil.

IRRIGATION IS ALL ABOUT THE SOILS

Avos are incredibly sensitive to phytophthora. This oomycete (type of fungi) requires an anaerobic environment (lack of oxygen) to survive so water-logged soils are perfect. To avoid this rootrot disease and sustain healthy yields, we need to find the sweet spot between saturation and dehydration. The biggest determining factor of this state is the TYPE of soil. “Why then, do some farmers install an irrigation system and irrigation schedule that doesn’t take soil type into account?” asks Bram with a sigh.

A lot of Bram’s work, currently, is in this discipline … so he has some more tips to share:

- Base everything off soil type: The type (micro / drip etc), flow (high flow / low flow), layout (groupings) and volume (how much to supply) of an irrigation system should all be based off soil type. Failing to take soil structure into account when planning irrigation will mean that you miss the sweet spot in terms of moisture management and end up with either diseased and/or poor performing trees.

- Know when to walk away: some soils are just not suitable to cultivate avos – by insisting on trying anyway usually ends up in tears.

- Be cautious of all the technology and tools in this space right now (probes and automated systems). There’s no replacement for the farmer’s footprints. Use an auger – look (and record) this and verify it against the probe reports.

- Use well-trained staff to maintain the system properly – make sure they understand how replacing a 20l/hr nozzle with a 50l/hr nozzle will affect the entire system and potentially damage all the trees. Don’t cut corners by using the dunces (cheaper labour) to handle maintenance. Rather employ people who will value your operation and understand consequences.

Bram explains that fertigation is not big in avos yet because there is still so much to learn although low flow drip is getting a foothold. Bram is advocating, with fertigating farmers, to only use the fertigation for additional supplementation like early season boron, calcium and zinc. And possibly at the end of the season, when you want a negative ratio between nitrogen and potassium in order to direct reproductive growth. He suggests that, in the middle of the season, you should come in with half organics by hand because that is when the rainy season is happening and you can’t irrigate/fertigate anyway. Incorporate enriched manure as a general feed. Focus on addressing deficiencies or higher needs in the shoulders of the season, when it is dry and then it can be done through the fertigation system. Bram is seeing success where this approach is being implemented.

“Fertigate on the shoulders of the rainy season,” is Bram’s advice

PLANTING

If soil prep was good; then planting the tree should be simple, here’s a couple tips:

- By now your cover crop should be robust. Cut it back if necessary and uproot where the trees will be planted.

- Dig square holes.

- Keep the soil loose (don’t prepare holes when the soil is soaking wet as this creates hard edges to the hole), the edge of the holes should have a ‘crumble-structure’.

- Add a little super-phosphate or bone-meal and lime in the hole, mixed with some compost and top soil. This will give a nice, rich medium into which the roots will grow actively. Bram has seen good results from this.

- Never plant tree lower than soil in the bag. Rather plant a little higher and mound side-soil up to the right height. As it subsides, it’ll settle in the right place.

- Straight after tree is in, mulch – this will also curb weeds.

- Only deal with weeds mechanically (no poison) and leave them in the field, where they fall.

FERTILISING (or not)

As mentioned, avos, unlike macs, are not good phosphate miners so your phosphate placement is extremely important. To complicate things, Bram explains that phosphate can get ‘locked’ very quickly. High microbial activity helps because the right bacteria are key to unlocking phosphates. Lots of organic acids are released into the soil when there is high organic matter. These acids loosen phosphates making them available for the avos. Without the correct organic content, microbe supplementation is required to ensure phosphates are being solubilised.

When it comes to synthetic fertilisers; Bram is not a fan. Not sure if I’m the only one who didn’t know how we came to use chemicals in agriculture but my mind was blown when Bram enlightened me; after World War 2 there were lots of nitrogen/nitrate-based materials available and no market for it (nitrates are used to make bombs). Humans already knew that nitrogen stimulated plant growth and so agriculture became an obvious market. Because supply was high, prices were low and farmers started replacing the traditional soil supplements of compost and manure with cheap chemicals. The chemical fertiliser industry was born. Once it had legs (and a marketing budget) it proceeded to grow into something that could convince the agric industry that it was superior to what came before. Since then, soils have declined in life and microbial activity. Reliance on chemical fertilisers has increased and disease pressure has also increased. Low resistance, low resilience = increased pest pressure.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/08/06/beirut-explosions-ammonium-nitrate/

Bram firmly believes that the chemical fertilisers are not superior to nature but he does appreciate that they have a place in farming, rather like vitamins have a place in human nutrition – they are sometimes necessary but they’re not food!

Here are a few points to consider:

- The restoration of soil health, depending on how depleted it is, is an extremely slow process but not impossible. Nature has an inherent power to reign and, sometimes, all we need to do is to stop interfering. Given that commercial agriculture itself is not a natural activity, we do need to invest in nature (soil health) so that it supports our crops.

- To live, soil needs ongoing nourishment (carbon), hydration (water), aeration (air) and warmth (sunlight). Removing any one of these will kill it.

- Soil life discourages disease.

- Soil life promotes pest & disease resistance.

- Healthier soils manage moisture better.

- Deliberate water management, focused on maintaining diverse soil life, is key to plant health. Over irrigation is often more detrimental than under-irrigating (and it’s expensive).

- Chemical fertilisers often kill microbial life. The salts, inherent in many chemicals, need to be neutralised.

- Cover crops support soil life and health.

Because most soils are not healthy enough to sustain and support an avo orchard, Bram does work with chemical supplementation, using a hybrid approach wherever possible.

If wood chips are placed around newly planted trees there needs to be some supplementary nitrogen to help the soil life kick off the decomposing process. Bram says that the first fertiliser dose (in month 1) is sufficient to meet any deficit that the wood chips might induce.

In support of this dose of fertiliser, Bram explains that when young trees first grow out of their “pot” it takes a lot of energy and minerals. Our soils are not usually that high in minerals and require supplementation to get the tree up and going.

Bram prefers planting more trees per hectare and keeping them small; this strategy impacts fertiliser applications in that there should be smaller doses, more often. This requires a mind shift from the old-fashioned fewer, larger doses.

Bram endorses a multi-release strategy as well in that you apply a mix of quick release with some long-release in one application. This also cuts back on the cost of application.

Foliar sprays in avos are very necessary to support flower development, flower opening, fruiting, and the first period after fruit set. Bram says this is extremely important. Boron and zinc are always in short supply in avos. These elements support healthy pollen, healthy fertilisation, fruit retention. In periods of high demand Bram applies foliarly as well as in the root area.

Avo flowering is incredibly energy consuming and, if you have adverse weather conditions like the hot-cold-hot-cold that we are seeing more and more often, the trees need something to relieve the stress so that it doesn’t do what comes naturally to relieve stress which is to drop its fruit.

Avo flowers are indeterminate which means it has a growing point and then auxiliary flower buds – there’s always growth coming through behind the flowering and this takes energy. Supplementation is important to avoid a drain of energy from the fruit into flush. This flush comes through to cover the crop and minimise sunburn; it is necessary and requires support. Calcium & potassium are needed.

Another period that would benefit from foliar feeding is the end of winter when there is limited root activity and reduced uptake of minerals from the soil. Boron and zinc are important in this phase.

What we’re learning now, with climate change and variations is that silica and certain forms of phosphates that boost the trees’ immune system can help them get through the stress of temperature fluctuations.

STAKING

Bram advocates removing the stake that comes from the nursery and using a larger one positioned outside the pot area; 150-200mm away from the tree. If the stake is too close, it inhibits proper branch development on that side of the tree. Tie the stake and the tree together with a loose untreated sisal twine. This decays naturally and you won’t need to come back- you also don’t risk damage if you forget to remove it. He was recently in an orchard of 7-year-old trees where plastic ties had been used in staking. A piece of plastic around which the tree had now grown was hanging – when they tried to remove it, the tree broke; showing incredible weakness at this point and, even if it hadn’t broken, it would always be compromised and weakened.

Staking can be a challenging practice as nurseries have rules around staking and deviation from these can compromise any recourse should something go wrong with your trees, so be aware of that and clear changes with the nursery.

SPACING

Once again, there’s no one-size-fits-all but Bram does have some guidelines:

- Consider the cultivar’s natural growth habit. Hass and Fuerte have very open growth habits –wild, wide, strong – they prefer not to be controlled too much, from a pruning perspective. They are suitable to a multiple leader shape. Ryan as well although, to a lesser degree. This makes these cultivars suitable to wider spacings like 8mx6m or 10mx8m. Bram would plant them at 7mx4m. “Maybe Fuerte at 7mx5m because they take longer to come into production and if you start pruning the tree heavily from an early age you tend to get more vegetative growth and less production,” adds Bram.

- Pinkertons, Lamb hass, Edronol, Gem®, & Maluma ™ hass are all much more upright growers. The angles of attachment are narrower but still strong because there is one bud per node (mac or litchi trees often have multiple buds per node making these attachments weaker). The wider an attachment angle, the stronger it is. The fewer buds per node, the stronger it is. Narrow attachments (resulting in upright growers) are better suited to closer plantings; Bram would go for 6mx3m or 6mx2,5m because they are easily manipulated into a central leader shape. Small trees are easier to harvest as the need to climbing is eliminated.

- Consider the orchard terrain when deciding on spacing.

- Never plant ‘square’ ie: 5mx5m. This is because when a tree’s roots find the tree root next to it, growth is suppressed. This suppression helps you keep the interrow more open. If it’s a square then you are always having to do heavy cuts to maintain a working area in the interrow. And the tree will always grow back. Thus, Bram suggests that spacing is always in a rectangle.

- Consider the ideal orchard height. Tree height is limited by row width and should be kept to 80% ie: an 8m interrow means height should be limited to 6,4m. This is for sunlight access. Another factor that dictates tree height is the spray cart. Make sure you can spray the entire tree effectively.

PRUNING

Bram starts working on shape when the trees are just 6 months old.

Avo wood doesn’t harden as fast as a mac and is far easier to manipulate but Bram says this is not necessary because of the wide crotch angles and natural open growth. It is therefore far easier to prune than a mac tree. Well placed cuts will easily stimulate horizontal branches. Apical tipping will redirect growth into side branches. Bram prefers this early management approach as it is far more gentle than waiting 5 or 6 years and then having to make big cuts. His most common resistance to this advice is that it takes too much time; Bram disagrees and insists that all it takes is one or two people dedicated to training young trees every day. By year 3 you’ll be getting a crop and ‘self-manipulation’ will come into play.

Large, untrained orchards are a different story and, if you inherit one of these, you’ll most certainly need chainsaws to cut back and open up to turn the large empty spaces inside the tree into productive factory space again. Avocados flower on the outside so what’s the point of large trees with nothing inside? He believes its far better to have more, smaller trees.

An older tree that has been brought back into a more productive space through aggressive pruning

TIMING

Bram warns that all farming activities should be based on the trees’ stage of development (rather than calendar-based). This can be challenging to manage and feel a little ‘loose’ but it is essential. Ie: just because the trees SHOULD flower in July/August, they don’t always, and orchards can differ from each other – it its therefore imperative to monitor, assess and react based on what is actually happening rather than what SHOULD be happening.

Programmes can be planned but should be regarded as guidelines, never cast in stone. Adjust programmes based on the cultivar, soil type, area and micro-climate of each orchard. For some this may require a complete mindset shift and a removal of the big wall calendar.

Bram emphasises that PRECISION farming is not just a buzz-word, it’s a very real and necessary strategy for farmers who want to perform better. It’s a management system, led by what’s happening in the orchard, not by what’s happening on the calendar. Another challenge to this strategy is how to incorporating multiple crops and which crops t give preference to if they all require the same equipment simultaneously … no one said it’d be easy. Sometimes it becomes as intricate as managing two sides of one tree differently; due to the difference in heat units experienced, trees may behave differently on either side necessitating that you spray on side two weeks later than the other. That’s what it takes to meet the tree, and it’s needs, precisely.

SMALL-SCALE BENEFITS

Large-scale farmers are less able to employ precision tactics. This is a competitive advantage that small farmers must hold on to. You might not be able to employ the expensive specialists etc, but you can pivot on a dime and be more precise than big farmers. Bram adds that smaller famers should enhance their competitive advantage by identifying their niche and focussing on that. Don’t copy the big guys – look at your own niche. Eg: a small farmer in this area should not plant solely Fuerte but rather 1/3 Fuerte, 1/3 Pinkerton, 1/3 Maluma. The Fuerte can be trickled into the market. Malumas can be exported (highly valuable in a specific slot). Pinkerton is high producing cultivar with specific characteristics and marketability. Also consider late season varieties and distinguish yourselves by carefully choosing your marketer in order to realise the best price. Consider smaller marketers who often target better and realise better prices, despite lower volumes.

Eg: there’s now a marketer who has broken away from one of the big companies. His strategy is to focus on first and last 8 weeks of the season. He’s not a packer. He’ll go directly to the growers and secure x quantity in a specific week (precision marketing). This is opposed to a 12-week programme where you dribble in over that time, fitting in amongst the bigger players.

PESTS & DISEASES

Although both macs and avos are susceptible, the major difference is that macs tend to suffer most losses through insect damage (pests) whereas avos are more afflicted by bacteria, viruses, fungi and nutritional issues – excesses and deficiencies of key minerals (diseases). Because disease is seen as a more internal condition, avos have picked up the reputation of being weak and difficult to grow but diseases are actually also environmental – they’re just a little more challenging to manage as they’re less visible and less understood.

Avo pests in Tzaneen are not a big issue and Bram believes in tolerating or allowing a certain loss to “nature” (pests) because nature is going to take it anyway. He believes avo farmers do not need to take a hard approach to managing pests.

PESTS

There are four main pests to watch for the avo-farmer to be aware of and monitor:

SUCKING BUG COMPLEX – (Stink bugs) Can be a concern. Infestation is more often localised as opposed affecting the whole farm. In the Tzaneen area it’s usually around the rivers and dams – probably related to the hiding spots and suitable host plants in these environments.

Bram explains that stink bugs are more often opportunists rather than indigenous avo pests. In Levubu and Nelspruit, where there are severe macadamia spraying regimes with harsh chemicals, avos have become a source of food for a range of sucking insects – they fly between macs and avos, dodging the sprays.

I couldn’t understand why a stink bug would prefer a hard macadamia nut over a nice soft avo. Bram explained that the stink bug is after the protein in the endosperm (nut/seed) of the fruit which is the nut in a mac and a pip in an avo. So, then it makes sense that he wouldn’t want to/can’t get his probiscis through all that flesh on an avo but is well-adapted to dissolve the shell of a mac and reach the relatively short way through to the nut. Stink bugs that do sting an avo are generally just investigating whether he can find food. If the avo is small enough for him to reach the pip, he may settle in for a feast but it’s not his primary food choice. Macs are far preferable. A lesion which is slightly darker than the rest of the fruit skin can be distinguished from about the second day after feeding takes place. With age this becomes indented and dark-brown to black, much like a hail mark. Internally the lesion forms a typical hard clot that is easily removed together with the skin when the latter is pulled off

Coconut bug (a type of stink bug) is more of a problem because it is less detectable; it’s a solitary insect and it lays solitary eggs, underneath the leaf – many throughout an area. Other stink bugs lay eggs in clusters. Coconut bugs are active early in the morning or late in the afternoon; and hide during the day. They’re more active in warm summer months when avo fruit is starting to produce oil. He also only goes for thin skinned varieties. Bram believes there is something in the physiology of the avo at this stage of development that the coconut bug needs. Coconut bug mouth parts are smaller than 2-spotted.

Coconut bug

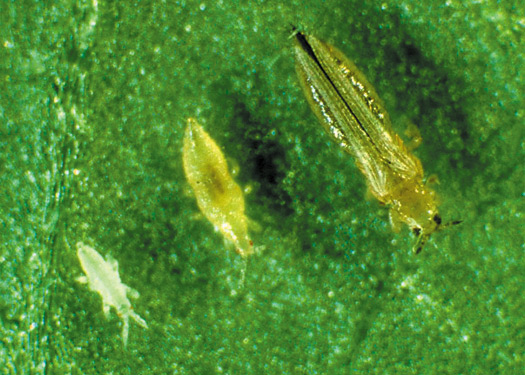

THRIPS – Besides a serious outbreak every 5 to 10 years these minute monsters are seldom a commercial threat. “And,” continues Bram, “if you have the right cover crops to host the right indigenous thrips, they will predate enough to balance the population.”

Two species of thrips attack avocado, ie the greenhouse thrips, Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis (Bouché), and the redbanded thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Giard). As a result of their feeding on leaves and fruit (De Villiers, 1980) chlorophyll is extracted and a pale to brown area develops. Distinctive blackish spots of their excreta are present on the damaged areas. Thrips damage is seldom found on fruit. Lately it has been discovered that the citrus thrips is becoming more common in places and needs to be monitored.

Bram mentions that there are also some excellent biological controls to support a softer approach. One such treatment is one I’d never heard of before; wettable sulphur! This is a mineral that the trees need anyway and it doesn’t kill anything, it just repels it. (Might lose a few staff members too). Sulphur is available through most fertiliser suppliers. Spray every 2 to 3 weeks, a total of 3 sprays. Problem sorted. Could it possibly be that easy? Worth a try!

There are many thrips, many of them predatory ie: they eat herbivorous thrips, so always be cautious about ‘controlling’ them

AVO BUG – Bram says some people get very excited about this pest but he doesn’t think it’s a serious threat. Ecologically balanced orchards will keep them in check.

Avo Bug and eggs

FALSE CODDLING MOTH – Bram says it seems like there is reasonably good natural control of this moth.

False Coddling moth

ACCEPTABLE LOSSES – NATURE FEEDS NATURE

Bram is passionate about farmers tolerating an ‘acceptable loss’ to nature. He explains; “Avo trees overproduce early in the season. They will always drop fruit. Before it drops this fruit, it emits a pheromone that attracts insects … a I’m-going-to-throw-this-away-so-come-get-it call to the environment. This is how nature looks after itself.” Bram says we need to understand natural flows in orchards and this is one of them.

SCOUT EVERYTHING AND WATCH TRENDS

Monitoring (scouting) is essential so that you can understand what’s happening. Unlike macadamias, no “nuking” is done … it’s more of a ‘shake the tree’-type scout.

It’s also very important that you scout EVERYTHING to understand the WHOLE story; don’t count only the pests – count the predators too. This way you can make more informed decisions. When you see the big picture, you might realise that everything is actually in balance.

Bram elaborates; “Record the counts and follow the trends. For example, if you have a count of 4 stink bugs, your programme might say you should spray but, if you also had 4 last week, and the week before and your predator count is also stable or maybe even increasing, you can look forward to a decline in stink bugs and an increase in the predators without spraying! You don’t want stink bugs numbers to be 0 otherwise what will the predators eat? They will die without any stink bugs.”

Bram believes the key is in monitoring trends. It’s also key to do year on year analyses eg: you can see that the same time last year you also had a spike in stink bugs numbers but it was controlled naturally within 2 weeks – this information will give you confidence and justification to hold back the chemicals as the predators have proven their power previously; you just need to give them time.

Bram’s concern is that the avo industry has a habit of following what’s happening in the citrus and mac industries and he believes that’s too heavy-handed. “It doesn’t need to get to this toxic situation for avos,” he pleads.

DISEASES

This is where avos outdo themselves … Managing the trees through this onslaught by, often invisible, micro-enemies, can be challenging. These are the main problems:

- FRUIT DISEASE:

- Cercospera sits on the skin, as little black dots.

- Antracnose (fungi) and

- General body rot (Botrytis & Dtiorella) only see after harvest – lies latent in the fruit until it starts ripening.

- Black spot shows up 3 months after infection.

Copper programmes control all of these diseases. Fuerte requires 3 to 4 sprays because of its thin skin which is far more prone to diseases. Black skin varieties require 2 sprays max. Ryan needs another one because it hangs much later – and there’s a longer period before it starts ripening.

Bram says there’s an opportunity for farmers to spray more effectively through timing. It’s a matter of assessing 3 elements; fruit size, orchard temperatures and moisture. It is important that all three are considered.

- Fruit size: Diseases only start attacking the fruit once it is larger than pigeon egg size, during the rapid growth phase when the skin is at its softest and most vulnerable to disease. Once the fruit reaches full size and starts increasing in oil content, the resistance to disease improves as oil blocks the development of fungi. Copper sprays, which are used to treat fungal infections, are only effective on the fruit until the rain comes and washes it off, then it ends up in the soil and has a detrimental impact on the GOOD, soil-based fungi.

Bram has noticed that many farmers start spraying too early because the 5% fruit on the outside of the orchard (which is easily observable from their bakkie window) is further developed than the 95% of fruit on the inside of the orchard. This means a wasted spray and all the related costs as well as unnecessarily poisoned soil.

2& 3. Temperatures and humidity: If it’s a cold spring with low humidity you can actually delay spraying and reduce your programme possibly by one spray. Hot humid spring with bigger fruit earlier on, you have to start earlier. No calendar weeks, it’s all about fruit development.

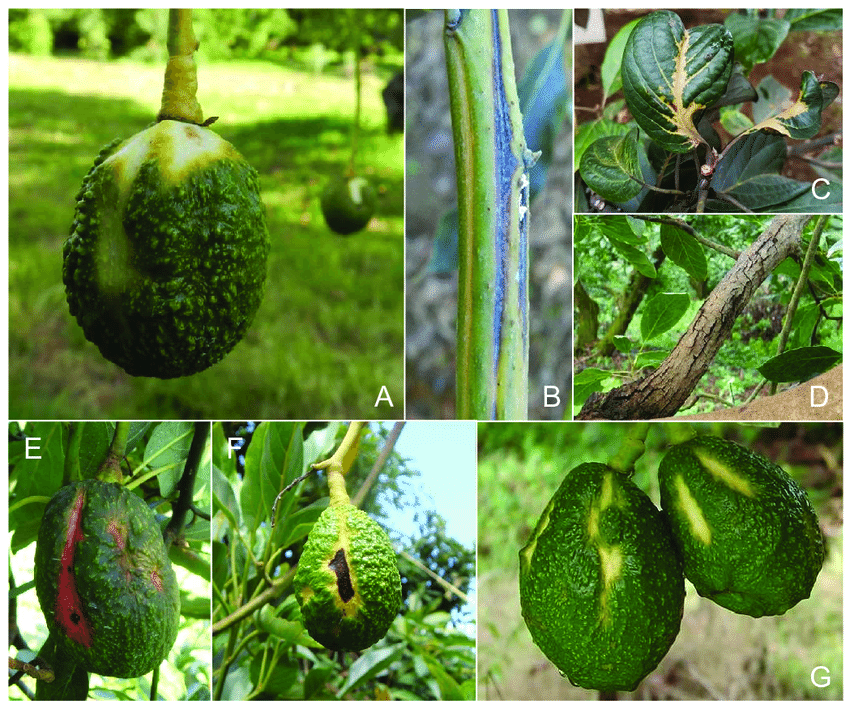

- SUN BLOTCH: This is a viral infection that can manifest in three ways: 1. Fruit damage, 2. No production, 3. Low production. Bram believes that when demand for trees was high and supply was low (remember the 4-6 year waiting list), some people took risks. It seemed that every ‘Tom, Dick and Harry’ saw the opportunity to earn a quick buck and started an avo nursery. Farmers, looking for a short cut, supported these here-today-gone-tomorrow pop-ups who didn’t have all the necessary controls in place and, he believes, in a few years’ time (next 5 to 10 years), they will be paying the price in the form of tree quality and orchard longevity because the trees are carrying the virus.

Symptoms of avocado sunblotch disease. Yellowish sunken areas on fruits (A); discoloured and necrotic depressions on infected twigs (B); distortion and variegation on leaves (C); cracked bark (“Alligator skin”) appearance on some mature branches (D); fruits with reddish colour areas (E); necrosis on severely affected fruits (F); multiple yellowish sunken areas in fruits (G).

- ROOT DISEASE – phytophthora. The susceptibility of avos to this fungus is what makes avo farming so challenging. Over-irrigation has intensified the issue as phytophthora thrives in water-logged environments. Ridging and land prep with careful drainage planning have improved the situation. The most common treatment of this condition in avocados is the phosphoric acid injection. 6mm diameter holes are drilled into the tree trunk and syringes with a fixed amount of acid are left in these holes so that the acid drains into the tree. Farmers used to do 3 rounds of these acidic injections every year but MRL (maximum residue levels) limitations have forced a reduction to 1.

Phosphoric acid being injected into an avo tree as a preventative treatment for phytophthora

If soils are well managed, there’s good drainage, good irrigation and fertilisation is well-managed, then phytophthora is not a serious problem. Injecting chemicals into the tree should be the last resort, not first. Phytophthora is a permanent feature in all water; we need to farm soils properly to prevent it infecting the plants.

- Rosellinia is another root disease, also known as white root rot. It’s been discovered fairly recently and details around it are still pretty sketchy – the University of Pretoria is monitoring it. It seems to attack certain trees rather than a whole orchard. It manifests as a white mycelium growth on the tree trunk, growing into bark. Once infected, the tree dies quickly, with most of the leaves still attached. Infections have been reported mostly in older orchards on seedling root stocks. Bram doesn’t think it’s the big issue researchers are making it out to be at this stage but he cautions that farmers should be aware of it.

Evidence of a rosellinia infection

POLLINATION

All flowers in the Laurel family are protogynous, which is a complex flowering system that prevents inbreeding. It works in that the flowers open twice, once as male and once as female – 2 days and it’s all over. But each cultivar is either A-type or B-type; A-cultivar flowers open as female on the morning of the first day and close in late morning or early afternoon. Then they open as male in the afternoon of the second day. B varieties open as female on the afternoon of the first day, close in late afternoon and reopen as male the following morning.

| A-cultivars

Hass, Lamb Hass, Pinkerton, Reed |

B-cultivars

Fuerte |

||

| Day One | Morning | Female | |

| Afternoon | Female | ||

| Day Two | Morning | Male | |

| Afternoon | Male | ||

Because of this synchronisation, many have believed that orchards had to be mixed in order to get good fruit set but subsequent studies (by Prof Robbertse at University of Pretoria) revealed that there is a lot of overlapping, caused by micro-climates. Eg: some trees will open early in the morning and others later on. This means that, within a mono-cultivar orchard, there will be males and female flowers present, enabling effective pollination.

Furthermore, the overlapping makes it difficult to plan cross pollination into your orchards, it either happens or it doesn’t. Bees also tend to cover a tree pretty comprehensively before moving to another tree so relying on them to transfer pollen between cultivars is possibly a little too hopeful. Genetic Studies show that, in orchards that have had pollinisers interplanted, most trees were still pollinated by their own cultivar. There also hasn’t been significantly higher production from interplanted orchards.

One thing we can be sure of though, is that a single avo tree cannot self-pollinate itself. Of course, the clonal orchards kind of nullify this security anyway.

HARVESTING

As mentioned, avo fruit does not ripen on the tree; it only starts the ripening process once abscised. So, how do we know when to pick? A moisture test, indicating fruit maturity, is done to tell when the crop is ready. Early in the season everything is picked with the fruit stem intact as removing it would create a wound susceptible to infection. Later in the season, the stem is able to come away on certain cultivars without causing damage.

The fruit is incredibly sensitive and requires a gentle touch. It needs to be placed in cold storage as soon as possible to limit the ripening process. Malumas have a higher respiration rate than other cultivars and are therefore particularly hasty ripeners – they need to be in a fridge with 6 hours of picking.

POST HARVEST

In the packhouse, fruit is washed and treated with anti-fungal washes. Prochloraz, the chemical that has been used up until now to disinfect the fruit, is being phased out. There is no acceptable substitute at this stage. This means that we are going to need to increase attention elsewhere to minimise fungal infections; like pruning (open trees with more airflow). Bram says we can also make sure there’s enough calcium and bring silica back into the mix (Both foliar and through the soil). If we supplement with these elements early in the season it will help strengthen skins which will have a higher resilience against disease.

Copper restrictions are already on the cards so we need to look for alternative anti-fungal remedies.

WRAP UP

Bram leaves us with three valuable pearls of wisdom to contemplate …

Farming is a science and an art.

More so than any other vocation, farming (especially fruit trees) is a science but it is also very much an art. Art comes into it from an intuition perspective; it also takes personal investment – an immersion of ALL a farmer’s talents and all-round knowledge. It’s about getting back to basics and working with nature; figuring out what’s right is often as simple as sitting down, doing some balanced research, and thinking about it.

Successful farmers are visionaries.

If you think in pictures, imagine your farm as a huge big ship; it’s a huge investment, built for the long-term. Turning it on a dime is impossible; agility is a challenge. You’ve planted your trees for the next 30 years +. This is why farmers have to look far into the future to plan their course. They need to be proactive rather than reactive. This is played out practically in choosing your markets and aligning your on-farm strategy, as an example.

Never look a gift horse in the mouth.

Nature gifts us 3 elements that are critical for farming; sunlight, water and carbon. We need to use them wisely, use them sparingly, but the bottom line is USE THEM! Most farmers are nodding at the sunlight and water thing but they’re wondering at the carbon … there’s an invaluable force available to work the soils into nutrition and protection for our trees – it just needs to be supported.

A massive thank you to Bram – even though his time is his currency, he gave it to us willingly. Forever grateful.

________________________________________________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wikipedia

SAAGA

Avodemia.com

http://blog.maluma.co.za/about-maluma/

http://www.fourwindsgrowers.com

https://www.westfaliafruit.com

http://www.agric.wa.gov.au/avocados

https://infonet-biovision.org/PlantHealth/MinorPests/Coconut-bug-1

https://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/insect-information/crop-pests/cotton/thrips.html

https://progressivecrop.com/2021/05/avocado-invasive-insect-pests/

https://insectscience.co.za/pest/citrus-false-codling-moth/

https://www.fabinet.up.ac.za/index.php/avocado-diseases/rosellinia-necatrix