What better way to start off our journey into avocados than an overview of the crop with one of the industry’s most accomplished, experienced and respected consultants! It has been a real challenge to “get into avos” … the change from sugar to macs was far easier; perhaps because many of the sugar farmers I knew were now eager to understand the mac option more intimately but the change from macs to avos is different. Avos have been around longer, the farmers are generally proficient and knowledgeable – farming them successfully requires another level of skill. I almost feel like I’ve emigrated to a foreign country. 🤣 Although very busy, Bram Snijder agreed to the role of ‘tour guide’ in this new territory by sharing what he knows about avocados – his input has formed the foundation of this ‘paper’.

But first; coffee! This is both what you should have as you settle down for some interesting content AND where Bram started his career. As you’ve guessed from his surname, Bram is Dutch but has been in South Africa since he was 13. He has a BSc(Agric) from Pretoria University where he majored in Horticulture. After varsity, Bram spent 20 years at the ARC, in Nelspruit and Kiepersol, where he did research on coffee for 15 years and then moved over to avos, litchis and macadamias. Although there are a few other exploits on his CV, he is still actively involved in subtropical crops, specifically avos, litchis, macadamias. He now runs his own, independent consultancy.

So, I’m sure you’ll agree that, with his highly relevant degree and almost 40 years of research, work and study into commercial subtropical agriculture, production, post-harvest management and marketing, Bram is more than qualified to teach us a thing or two (or 101) about AVOS. Oh – and he’s also the Technical Director of SAAGA (South African Avocados Growers Association), the Chairperson of SALGA (South African Litchi Growers Association), and a Board member of Subtrop.

CONTEXT

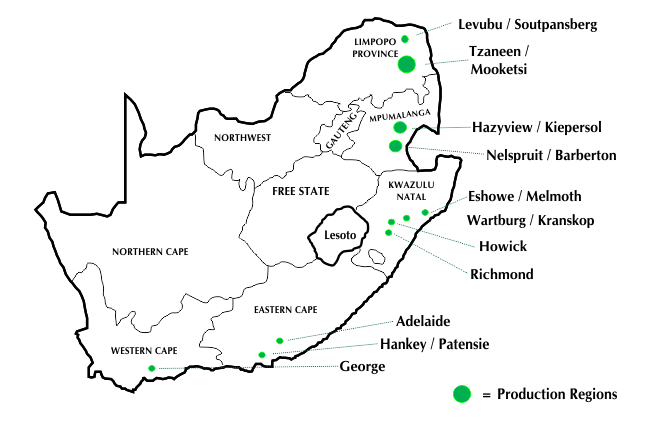

Bram is based in Tzaneen, in the Limpopo Province, the heart of avo country in South Africa. Most of our avos are grown here and in the neighbouring Mpumalanga province although increased demand and the pursuit of year-round production has seen avos spring up in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern and Southern Cape. Our crop is now in the region of 132000 tonnes but the industry speaks in terms of 4kg cartons so that’s about 33 million cartons. (SAAGA website https://avocado.co.za/sa-avocado-industry-overview/ )

Tzaneen, Bram’s home town, is the heart of the South African avocado industry.

Currently the ratio of crops in Tzaneen (exc Letsitele which is about 30kms to the east) is 80% avos, 15% macs, 2% litchis and 3% mangoes. I wondered whether the recent, crippling avo season would change this ratio as farmers change from avos to something more financially viable but Bram doesn’t think so. He explains that the only real issue the South African avo industry faces right now is limited markets. As soon as that has been addressed the situation will correct.

As mentioned in our most recent TropicalBytes story https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2022-12-jaff27/ , the South African ‘window’ in the Western European market is currently dominated by Peru. The Ukraine-Russia war is causing an issue in the Eastern European market as a lot of ‘green skins’ and large size avos have traditionally been sold here. This war got heated at the beginning of the 2022 avo season and we were left without a plan to deal with the situation … Spain, Israel and Morocco also had a bumper crop (that wasn’t declared or disclosed) and lasted way into our season so we really just had a lot against us in 2022.

Bram is positive about next season; here’s why:

- Spain, Israel and Morocco forecasts are down; back to normal crop levels. Bumper crops generally happen once every 10-year cycle. After 2 years of brilliant weather they are, once again, experiencing drought conditions. South Africa had a bumper crop (along with most of the subtropical world) in 2018, when we produced 21 million cartons, and we haven’t repeated it since, although Bram suspects that this year might be a big one for us, based on the flowering he’s seeing. His prediction is around 18 – 18,5 million 4kg export cartons, which will equate to a total crop of around 33 million cartons including local marketing and processing volumes.

- New markets are about to open up and you can read all the details on this in our September story https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2022-9-newsfromtheroad/

- The price drop was a good thing. I know that might sound shocking but there’s reasoning behind the view … Bram explains that market corrections, like this price drop, shake the ‘dead wood’ out of an industry, leaving the healthy farms, ethical suppliers and sustainable businesses to continue in a less cluttered market. And even the ‘live wood’ is forced to take a careful look at their operations and rethink everything; emerging as a tighter, more refined and deliberate enterprise. There’s always value to be found in a struggle. Bram continues, “The last three years haven’t been easy. COVID sparked a cost hike that has drastically reduced the bottom line. And now the boys are being separated from the men.” Although Bram is an integral part of this industry that is being purged, he insists that egos have needed correcting. “Although, for fruit farmers, humility is all too familiar; fruit’s high perishability factor means there is only ever a week or two between financial success and financial devastation”. Macadamias, because of their long shelf-life, do not gift their farmers with the same grounding.

On that sobering note, let’s meet the new chap crop …

MEET THE AVOCADO

Avos are from the Laurel family which is typically found in tropical forests. They are evergreen trees with thin-skinned ‘berries’ as fruit. Lauraceae flowers are protogynous (this means they change sex fluidly – something humans seem to have picked up lately as well 🤔 maybe we eat too many avos?) This complex flowering system prevents inbreeding.

Avos are native to the Americas and was first domesticated by the Mesoamerican tribes more than 5,000 years ago. Then, as now, it was prized for its large and unusually oily fruit. The tree likely originated in the highlands bridging south-central Mexico and Guatemala. Its fruit, sometimes also referred to as an alligator or avocado pear, is botanically a large berry containing a single large seed.

The species is variable because of selection pressure by humans to produce larger, fleshier fruits with a thinner skin. The avocado fruit is climacteric (meaning it matures on the tree but ripens off the tree). The pear-shaped fruit is usually 7–20 cm long, weighs between 100 and 1,000 g and has a large central seed, 5–6.4 cm long.

The plant was introduced to Spain in 1601, Indonesia around 1750, Mauritius in 1780, Brazil in 1809, the United States mainland in 1825, South Africa and Australia in the late 19th century, and the Ottoman Empire in 1908.

The word avocado comes from the Spanish aguacate, which derives from the Mexican word āhuacatl which goes back to the proto-Aztecan *pa:wa. In Molina’s Nahuatl dictionary “auacatl” is given also as the translation for “testicle”. (And now we are never going to see an avo the same way again! My apologies. 🤣)

The modern English name comes from a rendering of the Spanish aguacate as avogato. The earliest known written use in English is attested from 1697 as avogato pear, later avocado pear (due to its shape), a term sometimes corrupted to alligator pear.

HISTORY OF AVOS IN SOUTH AFRICA

The first avos hit our shores in the late 1800s, in the form of the big Natal butter pear. It seems to have been fairly quiet for the next 60 years until the Hans Merensky foundation (Westfalia) started planting in Tzaneen and Kiepersol areas. The 70s and 80s were spent finding solutions to a range of industry-related issues including transport temperatures, post-harvest quality and a number of production issues. As mentioned, the high perishability rate of avos makes it a completely different animal and much was done to tame it in the final decades of last century.

The real boom kicked off in the early 2000s. Peru stepped into the ring at about the same time but have outpaced us completely.

GLOBAL INDUSTRY

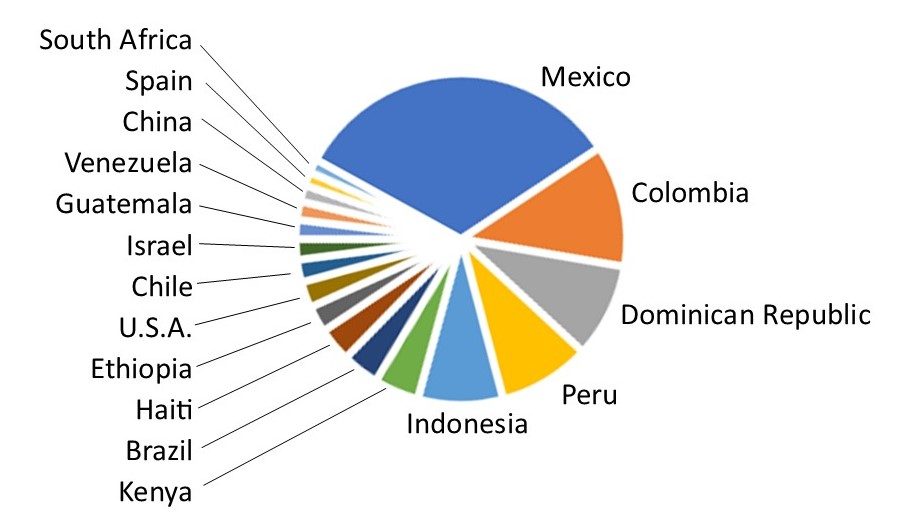

We’re around 17th when it comes to avo volumes produced; small fry in the grander scheme.

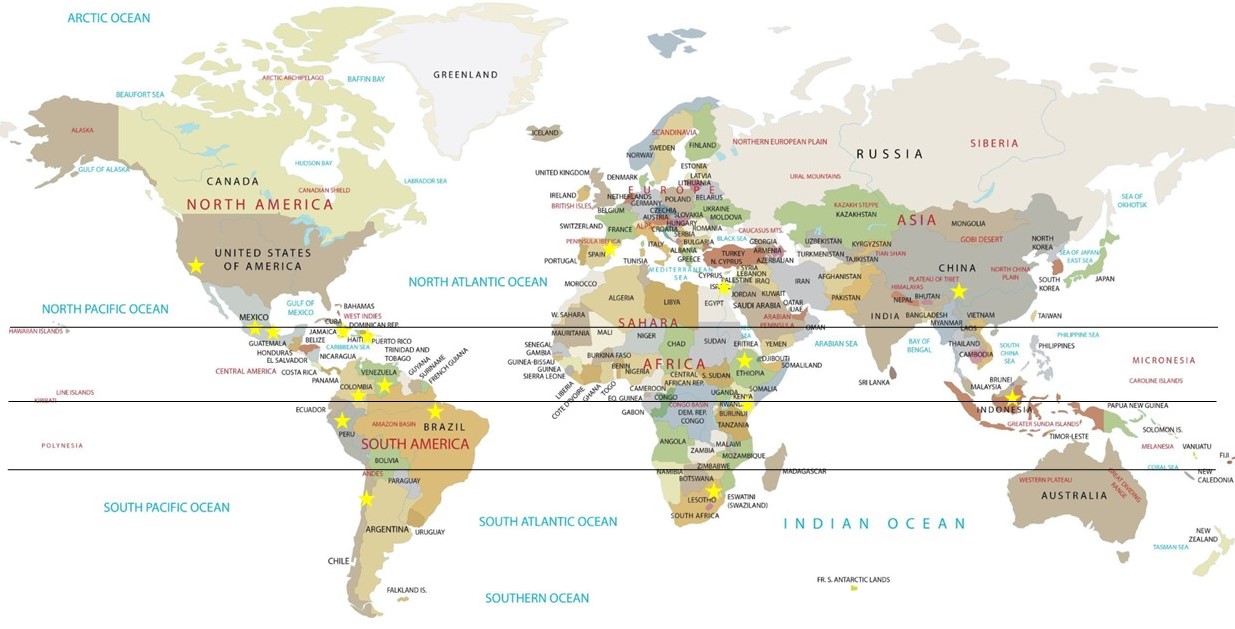

Below, I have pinned (starred) the top avo producing countries of the world and you’ll notice that we’re far further south than any others but there are a few countries, in the Northern Hemisphere, who are even further away from the tropic of cancer than we are from the tropic of capricorn. Climate also has a lot to do with topography, altitude, ocean currents and many other factors.

FUTURE OF AVOS IN SOUTH AFRICA

None of us have a crystal ball so here’s Bram’s view; he is very bullish about the industry but he also foretells of much restructuring with the successful farmers planting and growing with a specific shopping basket in mind ie: I am planting this to supply Japan’s housewife or I am planting this to supply local oil producers etc. And that made me think we should flip this story on its head! Rather than starting at the beginning, as we usually do, with land prep etc, we should work backwards, starting with the market … through the journey we’ll cover both practical facts like cultivars and pests and intertwine Bram’s understanding and advice.

South Africa’s avo growing regions

AVO MARKETS

When Bram sits with his clients, his first questions are based up to 10 000 kms away; he wants to understand where their market is; who do they want to supply. And then he helps them to farm avos for these markets. At the end of the day, it’s all about SELLING the avos we farm. We can grow until the cows come home but, if we can’t sell what we grow, what’s the point? I’ve termed this market-based farming.

If you’re already established, Bram analyses what you have and links that to a market. The market and/or the route to that market might be different to what you’ve been doing but most people call in consultants because what they’ve been doing isn’t working … if you call Bram, expect a broader consult that incorporates everything from A(vos) to Z(urich).

The general rule is that countries closer to the equator and at lower altitudes (therefore experiencing more heat units) produce fruit earlier in the season. But, within every region there are early, mid and late areas which are determined by the local micro-climates. Hot, low areas tend to come into season earlier Eg: the Ofcolaco/Harmonie block (about an hour south of Tzaneen) is a bosveld (bushveld) region and is an early area – the harvest ends end Jan/early Feb. The Mooketsi valley and Letsitele areas are also early, for the same reason. Haenertsburg (higher altitude) is a late area with the fruit hanging until Oct, Nov, Dec.

This is why the Cape is such a late season area – because it is so far south and therefore cooler.

Bram explains that generally, Tzaneen and Nelspruit tend to be in the ‘blood bath’ period of the market – middle of the season, when everyone’s avos (Peru included) are on the market. Further complicating this is the high probability of frost in some areas which prevents fruit being hung later in the season (to take advantage of higher late-season prices; 10 June is about the cut-off for frost areas. And, if you manage to get through winter, the summer is waiting on the other side … Therefore, although Tzaneen is a great production area, it often realises lower prices for its produce. Bram suggests that all farmers look for empty windows in the market (when prices are higher), micro-climates on their farms and grow cultivars to suit eg: a late-season, black-skinned variety that will fetch a better price when Peru is out of the market and before the northern hemisphere starts coming in to the market.

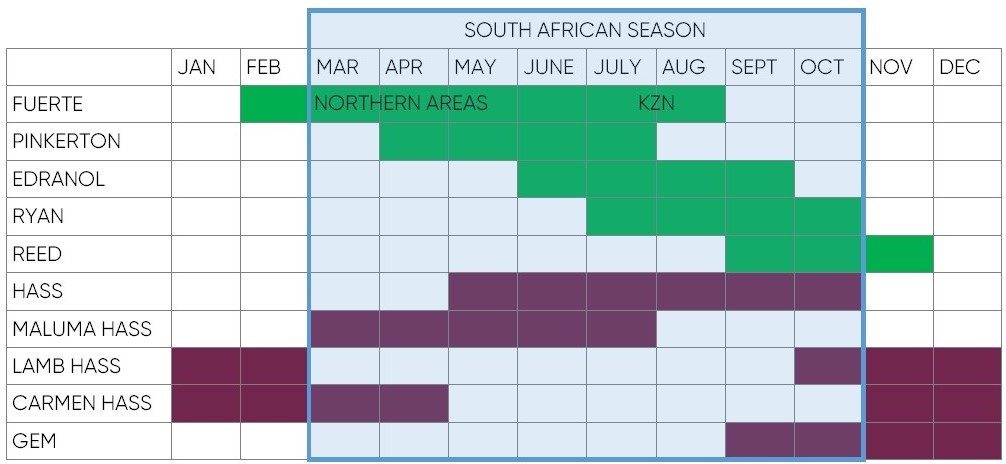

Avos ripen at different times, depending on the environment (area, climate, altitude) they’re in but this is the general window for each cultivar: (our Avo 101 poster also summarises this nicely)

Note: Green = green skins, purple = black skins.

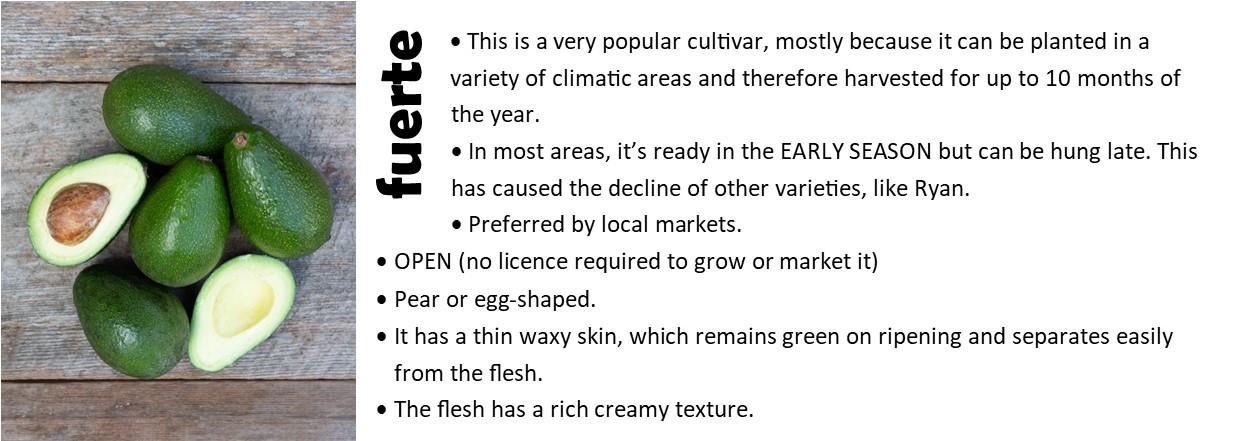

Bram says that local markets prefer green skinned varieties like fuerte.

And, when it comes to supplying the international markets, black skins travel best, reducing your risk, although Europe (mostly eastern Europe) is still very much an overall market place where you can sell your green skins as well (fuerte/pinkertons). Prices are higher early in the season so take that into consideration.

The bottom line is: as a grower you need to know where in the market you want to be, who can connect you with those markets and what variety do they want.

MARKETING

Bram explains that selecting a marketing ‘partner’ has become a bit of a sticky issue in the avo industry and I smile as this is all too familiar. It seems that farmers, regardless of crop/produce, always seem to end up being price-takers; something that ham-strings them, causes frustration and inevitably, friction.

The avo story currently is that bigger exporters are now mostly share-holder companies. Part of the deal is that you must market EVERYTHING through them and then you’ll get your rebates back otherwise rebates are reduced. Bram suspects that this condition will be challenged in the near future, especially with markets opening up. People will want to market green skins through one company because they have the right market for them and black skins through another because of their markets; so, being able to choose would be better for the farmers. But locking farmers in benefits the pack houses. Age-old wrangles. Ultimately, Bram thinks the share-holder rules and regulations might have to loosen up to accommodate farmer demands. There are commercial pack houses around that pack for more than one exporter and these offer a model that’s going to grow in popularity.

The root of the problem (pun intended 😁) is that a farmer’s ‘stock’ is in the ground for at least 30 years. Conversely, markets, climate and just about everything else is very fickle and can veer off course in 30 hours. If a farmer is already locked in to his stock, he, at least, needs marketing flexibility to be able to survive and keep up with the change.

Bram advises that farmers try to stay ahead by looking ahead; focus on the markets that will be unlocked. Even though these might not be on the table right now, it is highly likely that they will be by the time your tree comes into production.

I can equate this to what’s happening in macadamias – the ‘crowd’ has been planting Beaumont whereas the visionaries have been leaning more towards integs, despite the growing challenges, because the future marketing prospects are brighter. I ask Bram what is the equivalent of an integ in avos … Bram says it’s the move from green skins to speciality black skins. This is because western markets are very focussed on ripening (they can see when a black skin is ripe), less waste, which is possible because the skins are thicker, and black skins just handle better than green skins.

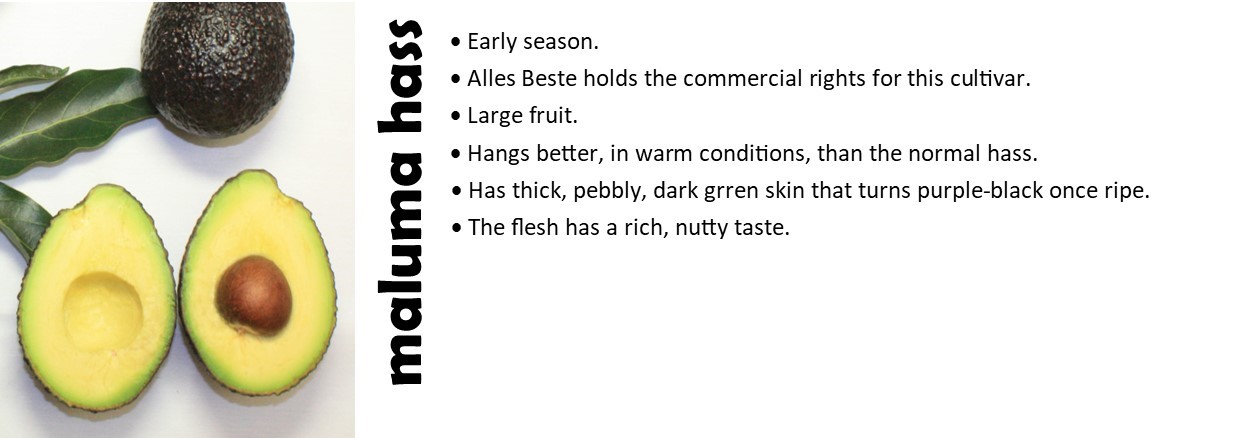

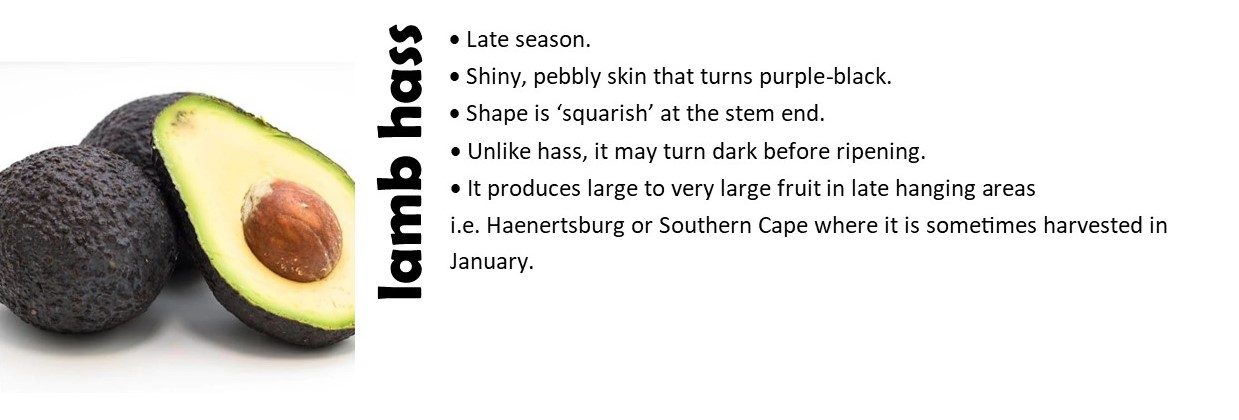

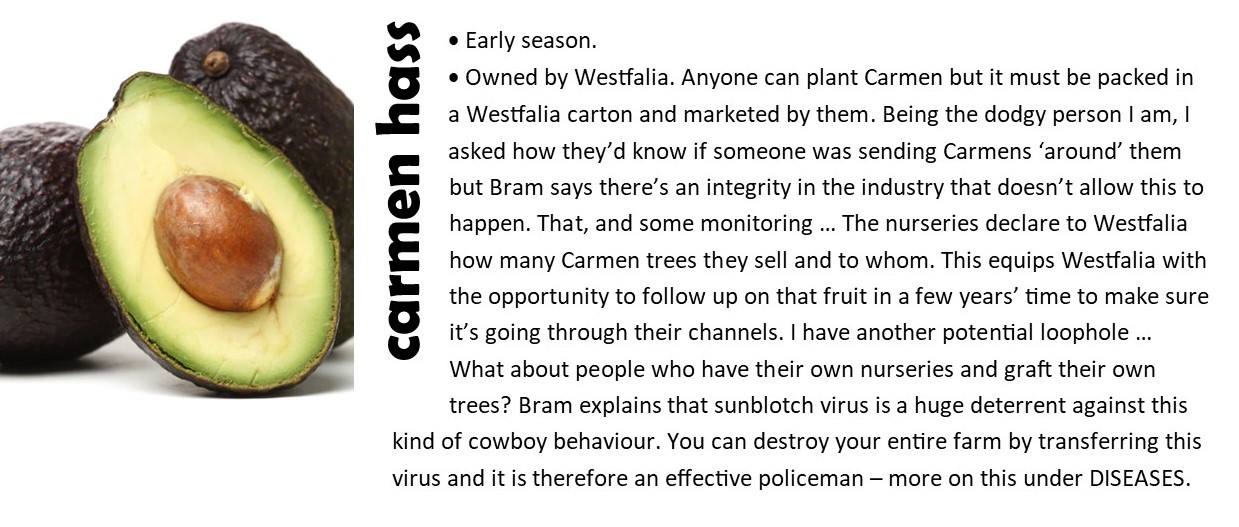

Having said that, Bram believes that farmers need to have more than one variety (it’s the same with macs). The popular advice is to just plant hass “you’ll make money” … but it’s not the case. Hass is very prone to producing small fruit which doesn’t fetch good prices (are we all seeing the parallels between a Hass and a Beaumont?) Supermarkets account for 80% of the avo market and they want bigger fruit. Maluma, Lamb hass, Gem … these are all alternatives that will be better than regular Hass. Bram adds, “Carmen is very hass-like but it’s very early so fetches a better price early in the season.”

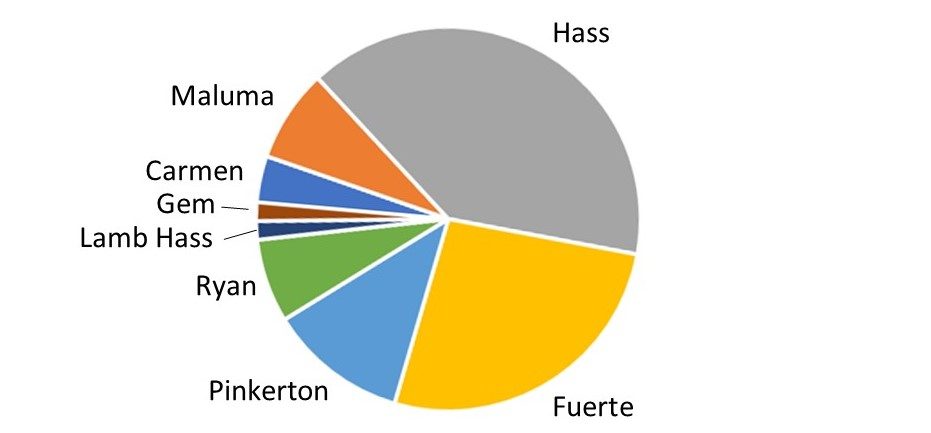

This is the current cultivar split in South Africa:

Carmen: 1.8%, Maluma: 7.6%, Hass: 49.5%, Fuerte: 20.5%, Pinkerton: 8.6%, Ryan: 5.6%, Lamb Hass: 1.3%, Gem: 2.3%; others 2.6%

Bram concludes that there are no perfect cultivars so split your risk by planting a range and focus your energy on marketing to get the best prices.

CULTIVAR CHARACTERISTICS

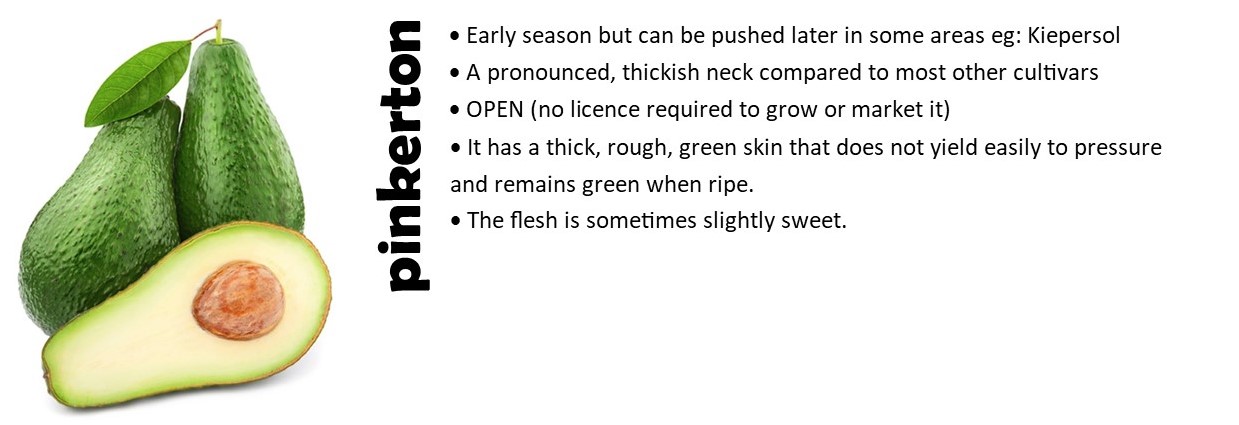

Green Skins: Green skins don’t travel well and are therefore better suited to supply the local market.

Black Skins: Black skins travel better because the skin is generally thicker, harder and less prone to infections – they are therefore better suited for the international markets.

Bram is encouraged by farmers who are getting really smart with their land and stretching their market across 7 or 8 months of the year by growing different varieties in different parts of their farms. This is very possible when you have a range of microclimates, it just takes a bit of research and experimentation to see what yields well, where and when (say that fast 20 times 🤣). Bram says he’s been learning a lot, in the last couple of years, about how the different late varieties behave and what their water requirements are. Especially as these often involve a double-crop. Like in California; the crop is set in spring and only harvested the following summer so the fruit hangs for almost 18 months.

At this point I was dumb-struck! Having taken time to understand the extreme perishability of avos, I now hear that they can hang on the tree for a year and a half! “Yup,” says Bram, “Avos don’t ripen on the tree. Especially in cooler climates where they can hang for even longer. They only start to ripen when you remove them from the tree.” So how do you know when to pick?” was my obvious follow up question … Percentage dry matter is the easiest of the reasonably accurate maturity tests.

Marketers will often assist in testing farmer’s produce and advising when to harvest. Usually, 23% dry matter is the minimum limit; anything less than that and the fruit is considered immature, but can be cultivar-dependent.

While visiting one of the upcoming Jaffs, I was lucky enough to witness them doing moisture tests in their lab. This is the machine and print out produced.

The moisture test is fairly simple and can be done in a household kitchen:

- Weigh the sample when it is fresh. (A)

- Dry the sample (a simple way to determine if the sample is fully dried is to take a shred of the dried flesh about five cm long, place it lengthwise between the thumb and forefinger, and try to bend it. If it is brittle and snaps cleanly, it is fully dried. If it bends without snapping, more drying time is required.

- Weigh the sample when it is dry. (B)

- Calculate percentage of dry matter: Weight of dried avocado sample, (B) divided by weight of fresh avocado sample (B) X 100. This needs to be a minimum of 23.

Bram explains that long-term-hanging is what the Cape farmers are doing … fruit is setting in September and they’re only harvesting in Dec/Jan the following year to take advantage of the seasonal spike in prices. The challenge is to get them through the winter and windy months. This means that there will be limited and isolated pockets of viable avo orchards that can take advantage of the brilliant prices realised over the Christmas break when housewives somehow manage to pay up to R30 PER AVO!! (Yes, that excludes me 🙄) Such pockets have been found near George, Heidelberg, Stellenbosch & Citrusdal. Conversely, avo farmers in the Eastern Cape; Adelaide, Fort Beaufort etc are struggling because this area is prone to severe cold snaps that literally put their plans for a great payday on ice!

Obviously, this ‘late hanging’ strategy doesn’t work everywhere and especially not in Tzaneen because of the summer heat; they must get early varieties off by end July and, for late varieties, by the end of September/ early October otherwise the fruit abscises itself and starts to ripen.

Nurseries & plant selection

ROOT STOCKS

Most farmers know this but anyone completely new to avos might find the grafting / clonal information interesting (and it wouldn’t be a complete AVO 101 without this bit) …

Seedling rootstock is when a plant is grown from a seed and this plant is used as the rootstock. Even though this plant grew from a seed that came from a specific cultivar, it is not a clone ie: its genetic make-up is not exactly the same as the plant that has grown from the seed that hung right next to it on the mother tree. They are ‘siblings’ (probably only half-siblings), not clones. The natural differences we see between all siblings is what makes this a bit of a hit-and-miss affair when you’re trying to create a formidable force of perfection and that’s why clonal rootstocks were developed. Imagine if they cloned humans … they’d only use the smartest, strongest, most beautiful people … not their weird-looking siblings!

Clonal rootstock is achieved when we generate roots from genetically identical plant material. The process is complicated, finnicky and requires a lot of precision. I learnt all about this from Covid Jaff https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2021-4-jaff-16/ whom we did a macadamia interview with … but he also has an avo nursery …

- The process starts the same way as seedling rootstock; by growing a shoot from a healthy, strong, disease-free seed.

- Budwood from the tree that we want to be the root stock is then grafted on to the seedling shoot.

- Once that has taken (showing growth), the whole plant is placed in the dark for 6 weeks so that it loses all chlorophyll (chlorophyll inhibits root growth)

- When it comes out, it is a white plant – still alive – and ready to shoot its own roots.

- The white stem is nicked with a blade, dusted with root stimulating powder and encased in a root trainer. Pic 1 & 2 below.

- Once roots are growing strongly the budwood for the producing part of the new tree is grafted onto the root stock material – Pic 3. At this point we have (potentially) 3 different cultivars in one tree – the seedling root, the clonal root stock and the motherwood.

- When everything has proven itself healthy and flourishing – Pic 4, the seedling root stock is removed and we have a clonal rootstock tree! Pic 5.

Aren’t humans terrifyingly manipulative 🤣.

Obviously clonal root stocks are superior because they are all exactly the same and have been selected from healthy, strong, resilient trees specifically suited to certain conditions. Bram says that seedling root stock would only be viable on virgin land (healthier soils), if at all. It is quicker to produce but you might pay for that in the long run. Genetic variability is the issue; some roots will be strong and healthy and others won’t which makes it impossible to establish a uniform orchard.

Bram’s recommendation is to put a little extra towards the orchard establishment budget so that all the anomalies can be removed from root stocks by using clones. It’s the one area that you cannot correct later. Buy QUALITY plants that are more resistant to root diseases. Remember that your soils are the other part of this equation and use root stock that has been tested and excelled in soils similar to yours. Root stocks hold the fate of the bearing wood and are well-worth the investment.

Fuerte budwood on Dusa clonal root stock

ROOT STOCK OPTIONS

Duke 7: This is the original clonal. It is good on high potential soils (well-drained, huttons, high organic content) and does better in cooler climates.

Bounty: This was selected in Kiepersol, when it was noticed that certain roots were faring better in water-logged situations. Development and testing verified the observation and Bounty is now recommended for poorer soils that tend to hold water. Bram suspects they prefer cooler weather -while he hasn’t done trials to prove it, he has noticed that, after 10 years, Bounty roots begin to struggle with excessively hot conditions.

Dusa: This is a new generation root stock that is more tolerant towards phytophthora. As with many developments in agriculture, this was a chance selection, this time from Westfalia. As with most avos, it doesn’t like poor soils and wet conditions but does seem to adapt well to a broader range of climatic conditions.

VELVICK: This one hales from Australia and is rather difficult to clone making it unpopular for nurseries. Its super-power lies in its ability to forage well for calcium and boron. Pinkerton, Maluma and Lamb hass need a lot of calcium and boron for fruit quality. This foraging skill makes Velvick an option if poor soils are the only option. On the down-side, Vervick is very sensitive to cold and has a high probability of dying in frost, especially in first few years. This contributes to its low popularity. Pinkertons are early varieties, often off the trees before cold snap comes but Hass’ hang into cold months.

ZERALA: Named after local mountains (Tzaneen) & LEOLA: Named after an area on a Westfalia farm, are two of the latest releases. Both have been developed in a Westfalia – SAAGA collaboration.

Both have high phytophthora tolerance, high productivity, seem to be have a wider climatic tolerance (cold & hot).

Others: There were also a few from Israel and California but none have performed well enough to become popular. Propagation difficulties have been the main issue. The research over the next year or two will be on closely matching a root stock to specific soils and climate.

Because people are planting in more and more marginal soils, a broader range of root stocks are needed, especially ones that cope in poorer soils. This is an ongoing area of research and receives funding from SAAGA and corporates.

Clonal root stock has just come out of the dark room and is being prepared with trainers to develop its own roots – this pic was also taken on my trip up north – another exciting Jaff story to look forward to.

What to choose: Bram cautions that the ‘latest’ is not always the best; selecting the right root-stock is very area-dependent and an old variety might be your perfect match. “And don’t just go with whatever the nursery has,” continues Bram, “rather do some homework and investigate which root stock suits YOUR soil and climate and then source the (reputable) nursery that can supply what you need.”

No one knows your farm like you do and the nurseries need that intimate knowledge when supplying you so don’t put them in the driver’s seat. Some nurseries will punt what works well in their nursery, regardless of how it performs in your land.

I wondered whether there were any “matching” limitations ie: can any budwood go on any root stock? Bram says that you can mix and match at will, “There have not been any serious rejection issues but there is a bit of size incompatibility with Ryan because it is a smaller, slower growing tree. This means you might end up with a small scion and a larger root stock in the full-grown tree but it’s not serious.”

Seedlings:

EDRANOL: If you’re going to go the seedling route, Edranol is what the industry has been using. Bram says this is a fairly stable cultivar in terms of variability although it is prone to sun blotch virus. The upside of this susceptibility is that it is a great indictor plant (shows you when it has the virus).

WEST INDIES: Bram says that, recently, guys have been importing west indian seedlings from Tanzania. He has his doubts about this option, based on having witnessed them struggle in this area; “they don’t seem to like our soils or our climate. They’ve come from the slopes of Kilimanjaro or from the old volcano rim region where the climate is far more rain-forest-like. We are drier and warmer here.” To conclude, Bram says farmers need to do as much homework on root stocks as they do on the scion (budwood). There’s a piece of life advice that I’ve always found valuable and it applies here; Don’t take advice from someone who’s trying to sell you something. Rather use an independent consultant to help you come up with suitable root stocks and scions that will achieve your goals and THEN go to the nurseries.

And that brings us to the end of Part One of Avos 101. Stay tuned for next month’s edition and Part Two which will cover:

- Land Prep

- Irrigation

- Planting

- Fertilising

- Staking

- Spacing

- Pruning

- Timing

- Small-scale farming

- Pests

- Diseases

- Scouting

- Pollination

- Harvesting

- Post-harvest

And when I look at it like that, I am so grateful to be able to present this kind of value to our readers. Thank you to Bram for his input and to all our readers for your continued support; looking forward to an epic 2023!

BIBLIOGRAPHY for both Part 1 & 2

Wikipedia

SAAGA

Avodemia.com

http://blog.maluma.co.za/about-maluma/

http://www.fourwindsgrowers.com

https://www.westfaliafruit.com

http://www.agric.wa.gov.au/avocados

https://infonet-biovision.org/PlantHealth/MinorPests/Coconut-bug-1

https://entomology.k-state.edu/extension/insect-information/crop-pests/cotton/thrips.html

https://progressivecrop.com/2021/05/avocado-invasive-insect-pests/

https://insectscience.co.za/pest/citrus-false-codling-moth/

https://www.fabinet.up.ac.za/index.php/avocado-diseases/rosellinia-necatrix

https://avocado.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Maturity-and-Dry-Matter-Testing-How-to-test.pdf