As humans, greed and jealousy are in our nature. The green-eyed monster rises without much encouragement. Over the years, I’ve worked hard to starve mine and can honestly say that the poor devil is now a mere shadow of his former brilliance. Instead of nurturing the envy I’ve been feeding up a wild beast called Celebration and I regularly nourish him with huge helpings of gratitude and jubilation at the success of others. And, boy oh boy, did he have a P A R T Y when we visited this Jaff. I encourage every farmer reading this story to do the same today; knock that green monster on his proverbial backside (Lord knows he has plenty to feast on here) and let’s honour this great Jaff together …

Jaff came recommended by Phillip Lee (https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2022-05-philiplee/); when I asked Phillip whom he considered as the greatest mac farmers of all time he said, “Oh, well ‘Jaff 27’ is most certainly on that list!” So, when I planned this year’s trip north, Jaff got the phone call and was immediately onboard, eager to share what he knows for the greater good.

Jaff is both an avo and mac farmer and although I had booked him for a mac interview, I couldn’t tame my curiosity to ask just a little about avos, especially in the face of the current crisis … his feedback makes up a neat, current agricultural review of the area: “This area has traditionally been a strong avo area because of Merensky. Merensky is an international holding company that includes Westfalia – the largest avocado farmers in South Africa – a legacy left by Hans Merensky who passed away in 1952.” Jaff says he was swimming upstream a little when he planted macs here, 20 years ago. It turns out that was a good thing as the world market is currently closing out avos in this area. For farmers further north, up to Levubu, where the avos come in earlier than they do here, there’s still space in the market. That’s why farms there are more evenly split between macs and avos.

He also explains that the local timber business is in trouble, and has been for a few years, because there is just not enough demand; many of the forests were planted for the mining sector. In the days of deep-level gold mines the timber was used for propping. Mining methods have since changed and very little support (timber) now goes into mining. Around here, all timber was owned by mining companies. In the last 30 years they’ve mostly divested. According to Jaff, foresters who bought the plantations are not making money. Those who can, plant macs.

So, I conclude that Jaff favours his macs over the avos right now but he soon sets me straight on that! Basically, Jaff says the two crops are so completely different; “a mac is like a weed – it’ll grow anywhere. An avo is like a turkey – you never know if it’ll make Christmas.”

Jaff is an insanely interesting person to talk to and I am not sure where to start. For me, his greatest value came in his perspective. Not only is he a farmer, he is also a part-owner of one of the country’s mac processing plants; and the ONLY one in Tzaneen. (Guess-the-Jaff players just got a HUGE clue there 😂) The ‘insider knowledge’ being involved further down that value chain creates is an invaluable foundation to on-farm decision-making. About now, I should also emphasise how deeply fortunate we are to be having all this time with Jaff – usually men in his position point me to a farm manager (of whom Jaff has 6 or 7) and while these men deliver value, it’s a different sort to the broad perspective we are indulging in today.

FARMER CONTEXT

Jaff grew up on a cattle and tobacco farm about 100kms north of where we sit today. When Jaff was about 12 his Dad called him over and said, “Boy – you see this farm?” “Yes Dad,” answers Jaff. “It’s my farm, understand! You need to go and make your own living,” clarified Jaff’s father.

And so Jaff never intended to farm and he went on to practice as a civil engineer. Appreciating the recreational freedom a small ‘plot’ would offer his young children, Jaff bought 15 hectares on Tzaneen dam, when his wife’s family put it on the market. Jaff explains how the ‘bug bit’; “There was a bit of ground so I planted some avo trees in 1991 and enjoyed it so much that, when the farm we are on now went up for sale, I decided to expand. Expansion is a costly exercise and farming is a gamble so I juggled both jobs until about 2012 when scale started to offer some security and I started farming full-time.” When Jaff’s current development is complete, he’ll have planted 760 hectares of orchards in total. One third of this is under avos, and the balance is planted to macs.

SAGE ADVICE

Jaff believes in farming a crop where it belongs. He knows both avos and macs belong here and so he focuses on those. “It’s all about viability,” says Jaff, “and viability is inextricably linked to market prices.” In simple maths terms, yield x price = viability. If yield is low, prices need to be high. If prices are low, yield needs to be high. Because farmers are price-takers, they need to lean on yield which is only an option where the crop grows comfortably. For macadamias in the current market, ‘yield’ is further broken down into total kernel recovery (TKR) and that can get tricky in this region. To explain that Jaff says, “Let’s look at Australia, where macs originate. There, the highest test station in the country is about 260m. Here, we’re sitting at 800m. Climatically that makes a big difference. TKR is inversely linked to altitude so it stands to reason that the higher you go, the less viable you’ll be. Obviously, I’m already at risk with the lower prices we’re getting now but, I’m in it for the long game.”

Yield is also related to scale and that’s where Jaff finds strength. When he started farming here he was told that if he had 15 hectares of avos he was a viable farmer. “Today, unless you have 250 hectares, you’re probably not going to make it,” he shrugs. “The market window for avos is just so short. If you hit it wrong, you’re toast. Economies of scale help cushion the impact.” Another advantage of farming at scale is the ability to buy the knowledge, expertise and equipment required to farm profitably.

CURRENT LANDSCAPE ON THE INTERNATIONAL AVO MARKET

I still wanted to understand the situation that is playing out in the current avo season; as we know, it’s been a horrible year for farmers with some having to PAY IN. Imagine investing in a crop all year only to receive an invoice when you send them to market. A completely devastating situation. Jaff explains … “In Peru & Chili there was a boom in the commodities business (coal, iron ore etc.) a few years ago. Part of the government requirements, to get the necessary mining licences, was corporate social investment that involved job creation and economic development. So, the mining companies had to develop something that would create jobs – no need for it to be profitable, it was just a means to getting a mining licence. Because it is a subtropical climate, many companies went into citrus and avo farming so this is where the large volumes of fruit are coming from. Unfortunately for us, their season overlaps ours and, last year, the Peruvian crop GREW by more than our total crop.

Peru and Chili ship all over the world. Jaff explains the implications; “It’s really not fair trade because there’s no capital repayment required; remember, the mines set these farms up for an ulterior motive; their ventures are expenses rather than investments.”

And then there’s another fall-out from the Peruvian avo-farming industry which is costing us all market in Europe. The Andes Mountains separate a narrow desert coastal belt on the west from a subtropical climate on the east. The snow on the mountains melts and supplies poor desert communities in the west with water for their quinoa and other subsistence crops. Remember that these are mining companies doing the farming; not exactly the most environmentally-concerned bunch … they built dams to use the snow water on their farms on the eastern side of the mountains. It was hugely successful … for them. But left a very sad situation for the farmers in the west. A documentary was made (one episode in a 6-part series called ‘Rotten’), laying the blame at avocado’s door and creating the impression that this is a crop that requires excessive amounts of water, when in fact, it had little to do with the crop the mining companies had chosen to grow and more to do with the way they had diverted the water away from poor communities. Regardless, the outcome of the viral doccie is that avos are now taboo with many European consumers.

The snow water from the Andes has been diverted away from the arid west to the lush east literally turning the taps off for small subsistence farmers along the coastal desert.

Turning back to the global market overview; what normally happens is that Israel and Spain supply the market early (around Feb). Then the Levubu crop comes in and they get fairly good prices. (This year it sat around R33 per kg in that first week of supply). Five weeks later, the price was R7/kg. Israel and Spain had a big crop this year so they stayed in the market a little longer than normal – 3 weeks. This killed the potential of the early market for sustained high prices. Tzaneen area then started sending its crop which resulted in the price tanking. On top of this, Peru arrived, in this already slumped market, and it just completely bottomed out. If you have the stomach for any more drama, we can add the fact that logistics were also a nightmare this season. Brace yourself, this is horrible …

If you’re in a ‘programme’ in Europe (eg: regularly supplying a supermarket) you can get a fairly decent price. You supply, for example, 10 containers per week to a specific customer. So, you send your 10 containers to Cape Town harbour and then the booked ship doesn’t arrive. 10 containers sit waiting …. another ship arrives but he already has 10 containers booked – so he takes that and some of yours; say 15 containers. Then another ship arrives 2 days earlier than he should and he also takes 10 containers. With this type of fiasco, it can happen that 30 containers can arrive in Europe in one week when it should have been 10 over 3 weeks. The supermarket lost the first week’s sales because that shipment didn’t arrive. But he still only wants 10 containers … but now there’s 30. He can chose the freshest 10 and leave the rest, which is now not the best quality because it’s been on the water so long. These ‘less than best’ avos are then dumped on the market which drives the price down. The more this happens, the lower the price goes. Logistics can literally wreck avo prices. Add this to the already depressed prices as a result of Israel, Spain and Peru and that’s what happened this year; Complete carnage.

“Is there ANY hope?” I ask Jaff. “Sure,” he smiles, in typical farmer optimism, “we can move on and hope that Spain and Israel don’t have as big a crop again next year and that the logistics gods give us a break.”

What about THE MAC MARKET?

Okay, I’m avo-depressed and turn the discussion to macs in search of a little sunshine … Jaff does not deliver sunshine 😟 he offers perspective; “The mac price has dropped from 80-odd bucks down to about 50. In 86/87 we had a slump, caused by a liquidity issue, when prices went from $12 to $4 (for kernel) overnight. It was a massive crash with 2/3 of the price wiped out. Now we’ve gone from R80 to R50 … comparatively, not so bad.” That confounding optimism again …

When Jaff started in macs, they accounted for 3% of the world nut market. Now, it’s less than 2%. “We’ve grown,” he says, “but we’re tinier than ever so there’s room to grow. With regards to prices, I think perhaps macs are becoming more of a commodity. As with anything, particularly commodities, the price could not keep going up. Two factors have colluded to stabilise it; 1. Exchange rates and 2. Market dynamics. Our prices were built on the back of the nut-in-shell market in China and the weaker rand. The rand has strengthened over the last 2 years and Chinese buying behaviour changed. Throw in a Russian war and rising input costs and, voila, you have a drop in prices.” Jaff concludes by saying he’s not concerned, “The mac price couldn’t just keep running away – it was due for a correction.”

I was also lucky enough to spend some time at Jaff’s processing factory and the man in charge there built on to my understanding of what’s happening in the international mac markets; The Chinese are starting to demand more quality. Their own crop is coming in and they can get that at next to nothing. In 2020 South Africa exported more than half the crop as nut-in-shell (NIS) but this year, it’s less than a quarter of the crop.

As explained by Jaff, there is still a huge market for macs but the Chinese supply changed the quality benchmark for everyone. Basically, the market we serve is now fussier, demanding better quality and bigger sizes. Size is based on the number of nuts in a kilogramme. The market is gradually demanding fewer nuts per kg. Over 22mm = 150 nuts/kg minimum. Current demands are closer to 140 nuts per kg minimum.

Jaff actually had to give back 4 contracts for NIS this season because they couldn’t meet the quality criteria.

Turning our attention to the kernel market … as the demand for larger NIS grows, we’ll end up cracking more (all the smaller nuts) and the kernel market will get more produce. Higher supply = lower prices. In the American market, the ingredient business drives trade. Pre-covid (2020) 18 000 tonnes of kernel was imported into the US. In 2021 it was 8500 tonnes, mostly because big mac-using products weren’t bought anymore, like the Subway Mac Cookie, which was discontinued. This year there was a slight increase to about 10 000 tonnes but prices remain depressed as there is still stock in the supply chain at the old prices. This old stock needs to work its way out before prices increase.

“So, while mac prices cannot continue to climb they way they have, they will stabilise,” concludes Jaff. He sums up his ‘big picture’ perspective with this statement; “Ultimately all we’re doing, growing macs and avos, is hedging the rand. It’s not about anything else.” And y’all thought you were farming! 🤔

Let’s get into the details …

| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 20 September 2022 |

| Area | Tzaneen, Limpopo |

| Soils | Deep, red |

| Rainfall | 1100mm annually |

| Altitude | Average: 800m |

| Distance from the coast | Approx 350kms |

| Temperature range | Average: 8°C – 28°C |

| Varieties | Predominantly Beaumont, A4, 814, 816. Also has Nelmak 2, 842 and 849 |

| Extent planted | 470 hectares macs & 140 hectares avos |

FARM CONTEXT

At last, it’s time to zoom in on what happens on this farm, when they’re not hedging the rand … of course. The day I was visiting, the clouds shrouded everything so we’ll have to take Jaff’s word for a lot.

We journeyed to the top of the farm, an elevation of 1050m – apparently the view is great. Jaff is concerned about macs over 900m so will probably stop planting them at that height and fill in the rest of the land with avos who have no trouble at elevations like this.

LAND PREPARATION

There is no doubt that we will learn the most from Jaff in this part of farming. Besides his civils background, it’s an activity that interests him and he’s proven he’s good at it. Here they do everything themselves; one of the farm managers employed by Jaff was a surveyor so he does all the setting out. The earth-moving machines all belong to Jaff which reduces costs and increases flexibility. Despite this, Jaff says he struggles to get establishment costs under R210k per hectare. I was fortunate enough to visit while Jaff was in the throes of developing and Jaff said that all the rocks in this field, shown below, will push this development up to R230k per hectare. Generally, Jaff budgets R250k per hectare for establishment, including irrigation.

Land in this area costs about R55k per hectare and you are generally able to develop about 60% of it increasing the cost of arable land to R100k per hectare. Then there’s the R65k – R70k per year (work on about 4 years) to maintain the orchards until they become productive. All in, that comes to about R530k per hectare. “At R80/kg, it works, but not at lower prices,” says Jaff, “we really hope prices improve.”

Jaff uses bull-dozers to rip and push contours.

The cost of development is the main reason why farmers cut corners – Jaff feels inadequate land prep is the most common mistake mac farmers make.

“Roots are the engine room of the tree so do not skimp on what you do in terms of soil preparation,” advises Jaff, “test, rip (and cross-rip), clear (rocks, stumps etc), get the pH right and supplement the soil properly, remember carbon, and your foundations will be firm.” The final step is discing the soil to a nice smooth bed.

Jaff doesn’t believe that macs require ridges. “Avos,” he says, “are another story entirely because of their susceptibility to phytophthora.” He did a trial in a new development, about 5 years ago, where they placed ridges in the middle of a new Beaumont orchard; 8 rows were ridged and the rest of the orchard was unridged. These 8 rows are the weakest of the whole block. “Yield, look, size, alles (everything) – they were way behind the others,” he says.

Much of the land Jaff develops to macs has previously been timber plantations. This excavator attachment is very handy to stack stumps, ready for burning.

In order to manage water run-off and soil preservation Jaff first cuts contours and then pushes rows in between the contours.

Here the ‘dozer is pushing rows between the contours. Jaff is concerned that it’s getting too steep as he goes down the hill. This is 4×4 planting (discussed under ‘Spacing’ below).

Jaff’s development plan showing the contour cuts and rows in between. Avos on the left. Macs on the right.

Whilst watching this machine work, I asked Jaff what he can see … “Lots of expense,” he frowns, “and I’m concerned about it holding up, especially with wet weather in the coming months. These banks are very steep.” We might need to reconsider the spacing as we move down the hill.

Here is a closer pic, taken from one of the roads. The gradient of the bank is more apparent from this angle. The stakes indicate where the trees will be planted.

Here is a closer pic, taken from one of the roads. The gradient of the bank is more apparent from this angle. The stakes indicate where the trees will be planted.

Avos will soon be planted in this field.

Avos planted on a gradient get, what Jaff’s manager refers to as, a ‘ridge on its back’. When working on a slope like this, there’s no point in creating ridges because terraces work the same way. The dozer cuts the row and pushes the soil over to the edge, creating the ‘ridge on its back’. The tree is planted into this soft soil.

ORCHARD ESTABLISHMENT

Once the land is properly prepared, it’s ready for planting. Again Jaff emphasises how vital it is that this soil prep is done correctly as most problems stem from shortcuts taken here and they’re next to impossible to fix once the trees are in the ground. Jaff believes the break-even point on macadamia yield is 2 tonnes per hectare. If you’re not getting that, Jaff suggests you take no more than a year, two max., to explore possible irrigation and nutrition issues but, if the yield remains low, rip them out and start again, with PROPER soil preparation, especially if they’re old varieties. Starting again costs a fortune but so do unproductive orchards.

The first task on any of Jaff’s orchard establishments is the electric fencing; he says, “it stops people wandering in, saying they’re lost and didn’t know what they wanted to steal.” As we know, theft in macadamias and avos is unfortunately extreme.

Jaff has two spacings he uses in macs; 7m x 3,5m (integrifolias and hybrids on more level land) and 4m x 4m (for Beaumonts on steeper gradients). Both denser than the norm. Tractor access into the Beaumont orchards is limited to the roads. 35m hoses are walked into the orchards to spray when necessary. Beaumonts require less spraying and are harvested once (after an ethapon spray) so they suit these steeper areas with limited access. If you are wondering how interrow maintenance is done in these steep, dense orchards, Jaff uses an excavator with a hydraulically-driven mulching head to clean where it is too steep to drive with the tractor.

I was so lucky to be on the farm when they were planting and can therefore detail the process nicely:

Bobcats with auger attachments are used to drill 320mm diameter, 800mm deep holes.

Some super-phosphate (40g per tree) and compost (10 litres per tree) is thrown in the bottom and the holes are filled with water. What I loved was that this water is delivered by the irrigation piping … as it is being unrolled, it stops to fill each hole it passes – how efficient!

Then a man with a spade comes and squares off the hole, to a depth of about 50cm.

He then removes some of the mixed soil and compost and prepares the hole for the tree, making sure that the top of the soil in the bag will line up exactly with the edge of the hole.

The tree is then placed in the hole, compost and soil filled in around it and it is securely stamped in.

The tree is then staked and, within the next few days, the base of each tree will be covered with some more compost and wood chips. 2050 trees will take 18 men 4 days to plant and complete the establishment process.

The irrigation man then comes past and inserts 2 drippers per tree, on stands.

Drippers are always on stands so Jaff can easily see the irrigation working. He knows it costs a bit more but it’s the way he likes it. They are always put on the uphill side. As the tree grows they move them back slightly.

There is no fertilising in year 1 – Jaff feels it’s a waste as there is enough fertiliser in the bag from the nursery as well as the additional nutrition in the compost and phosphate to keep it nourished while the tree is establishing itself.

Jaff has refined his process and is about to plant another 250 hectares with an American company, on the farm next door which is currently under blue gum; a R170 million project.

All trees come from established nurseries with a proven track records – Jaff appreciates the expertise involved in growing and grafting young trees and doesn’t want to get mixed up in that.

Here are brand new 842s planted 7m x 3,5m. Note how the rows follow the contour lines.

To maintain orchards, Jaff poisons around the tree and then slashes everything else. He is cautious with herbicides, knowing the risk to the trees. His main concern, with excessive vegetation, is the risk of fire.

Strong flush on new trees.

Avos will be planted on to this hillside across the valley. Ridges have been pushed.

Half way

CULTIVARS

Jaff says he has no advice on cultivars – “it’s all too farm-specific. I was lucky when I started because Merensky School had a trial block I could look at.” Beaumont was very popular back then but he believes the ‘honeymoon’ is over, for 2 reasons: 1. their nuts get smaller as they age (by looking at a Beaumont nut, Jaff’s able to (pretty accurately) tell you which orchard it comes from based on the orchard’s age), 2. their nuts are almost always lower grade styles, fetching lower prices.

“Beaumonts were the banker but not anymore,” says Jaff, “and more than half the nuts planted in past 5 years are Beaumonts so guys are in for a big surprise.” I hear you asking why Jaff continues to plant Beaumont – remember, he ONLY plants them on steeper slopes, at a 4mx4m spacing, where none of the integs are really viable.

According to Jaff, which cultivars are working for him right now?

Jaff won’t commit, “They don’t all work the same on every farm and it’s very market-driven at the moment. If you want to survive, bottom-line is that you need to produce more kernel so whatever does that on YOUR farm is what I recommend. I have 344 – which give me 7t/ha but only a 26% crack out. So, while it’s a lovely tree, it’s not producing enough kernel. A4, 816 – these are better. In the region of 34% which is good for this area – the odd 38% or 40% but those are seasonal exceptions. You have to remember that this is not the coast where they get 42%, nor is it Levubu where they can expect no more than 28 – 30%. It’s all climatic and, for this region, 34% is a good crack out. We need to farm the cultivars that can deliver that TKR, in this climate. We are dabbling with a few of the newer varieties – A268, A203, 772 – but it’s too early to tell whether they’ll work … this is a 10-year assessment,” laughs Jaff.

The new development currently being rolled out is being planted with A4, 816, Nelmak 2 and Beaumonts where it is steep. The Nelmak 2s are included in response to the Chinese demand for bigger nuts.

Jaff advises that, when selecting cultivars, mac farmers move away from farming nut-in-shell and focus on growing kernel.

And what about the quality of the kernel? Jaff says that he believes that this level of detail is a relic of all the research done in the 70s when they were developing the mac industry. Obviously, they needed comprehensive precision when it came to developing and cultivating varieties but he says we’ve moved on from that. Now there are a couple of varieties that’ll roast darker because of the higher sugar content but, apart from that, it’s fairly simple; bigger is generally better. The market is not as discerning as we think. Having said that, 1S (small wholes) is a popular … for the chocolate-coating market.

Here’s another exception to Jaff’s aversion to Beaumonts; the lower parts of this field, bordering the river, get incredibly cold so Jaff has chosen to plant the hardier Beaumonts on lower 1/3. Integs get the warmer, elevated seats. Cold is always relative and here, it’s not about the trees dying but rather, about the flowers being damaged in the cool snaps lingering into Spring – Beaumonts flower later and Jaff’s hoping they’ll miss the freeze.

IRRIGATION

There a couple significant main points Jaff wanted to land in this story; the first was on land prep and another is irrigation – he wants to share how, since installing probes, he’s been astounded at how much they have been over-watering. There are 50 probes across the farms and Jaff watches them all closely. He finds the accuracy and insight invaluable. Just last night he noticed how one probe was warning of dry soils so he gave the farm manager a ring. He explained that he had misread his load-shedding schedule and, when he wanted to irrigate that area, there was no power. Happy, Jaff could rest knowing that the farmer was on top of it and the situation would be remedied as soon as the power came on.

Besides being able to reduce the amount of water put down (and all the associated costs of irrigation) Jaff can also track exactly how much each block uses and when it uses it.

Over last 8 years Jaff farms have been migrating from micro-irrigation to drip which has further reduced irrigation costs. It has also made a difference to how much they can develop which is of key interest to Jaff. He is now focussed on how little water they can use, and still deliver an acceptable yield, as that will determine the extent of development possible on the allocated water rights.

Jaff dropped another little pearl during this discussion that I consider worth sharing; “Large tree canopies shelter the soil, keeping it cooler and reducing water loss so don’t assume that bigger trees need more water; I’ve learnt they don’t.”

Another advancement in this arena is the move to fertigation. It isn’t all smooth sailing here because of the high rainfall (1100mm annually) and they’ve had to run the fertiliser programme in 2 parts; fertigating in the dry season and applying granular fert in the rainy season.

Two (of many) holding dams. The one on the right is newly built and rests on top of the farm, ready to supply the 180 hectares being developed below. When Jaff filled the 20 000 cubic litres it LEAKED! They had to empty it and redo the 3-way welds.

Jaff says they save on irrigation capex by handling installation themselves, following professional plans. They also built and equipped this fertigation plant themselves.

Fertigation for 70 hectares done from this facility, built in-house for under R200k. The first quote they got was over R1mill and inspired the ‘boer to maak ‘n plan’ (translated: farmer to make a plan).

The mixing tanks are 1200 litres with an agitator. Water is pumped in the top, all controlled by blue tooth off the farmer manager’s phone. When ready, the fertiliser is sent into the irrigation system.

Each new development has a facility like this and it includes accommodation for 2 operators who manually control the pumps. Jaff doesn’t believe in automating everything. Things need to be reset after load-shedding and people need to be present, on the ground, keeping an eye on everything.

Jaff’s water supply is from local rivers and his own boreholes.

PESTS

Under this topic, Jaff shares the two most important factors that he’s had to learn in the past few seasons:

- There are more pests now than ever before. “Years back,” he says, “the pests were fewer and the chemicals were stronger.” Now; the reverse is true. Compounding the issue is larger trees. Jaff is concerned that the chemicals are so soft that multiple applications are required. One of his farms was sprayed 7 times and he still got a 5% USKR.

Jaff has had to change his view on scouting and decisions taken from the counts. Orchard maintenance has now become a huge cost – as much as harvesting. Scouting and pruning have been prioritised. Everyone on the farm is now trained to scout and they do it constantly, whilst going about their other tasks. If stink bugs are found, they are sprayed that same night, before they move or breed. Previously, Jaff would wait for a count of 7 bugs and then spray the whole farm, which takes 2 weeks. He’s realised that all he did with this method was waste resources.

- Pruning is key to pest and disease control. Jaff explains how pest pressure has changed the way he farms. Cubic metres of canopy per hectare relate to crop and he has always farmed large volumes of canopy to deliver the yield he required. He was getting up to 10 tonnes per hectare on some of the orchard blocks but “those days are gone” he frowns. With the pest pressure nowadays, he has to reduce canopy volume (to allow effective spray penetration) and prioritise pest control.

Stink bug causes the most damage on Jaff’s farms but he also struggles with False Coddling Moth (FCM) & Macadamia Nut Borer (MNB) in the beginning of the season. “Last year they gave us a hiding” says Jaff who monitors moth damage by what comes out of the dehusking plant predominately at the beginning of the season.

Sprays administered in high rainfall are often ineffective; making Dec/Jan difficult months in this area. Hence Jaff’s most significant damage is from late stink bug.

2020 was a bad year here; the crop was low and USKR (UnSound Kernel Recovery) was high. Jaff set about investigating ALL the potential problems and came up with a list of about 10 items. He then devised a plan of action for each and got to work. Dry flower was one item on this list that he has dealt with by spraying fungicides. 2021 was better but, in hindsight, Jaff is convinced that the number 1 factor in 2020’s poor results was climatic. For more on this see PRODUCTIVITY.

CROSS POLLINATION

Jaff takes a while to respond when I raise this topic. He’s not convinced that cross pollination is a major factor in results. He’s considered this carefully, across outcomes of many farms both interplanted and mono-cultivar. Subsequently, he plants pure blocks of about 3 to 4 hectares in size. He says that irrigation infrastructure is more cost effective with smaller block sizes.

Jaff does have numerous bee hives across the farms and says that the surrounding blue gum plantations are densely populated with bees.

PRUNING

This is where we encounter, what Jaff believes to be, the second biggest issue mac farmers are currently facing; trees that are too big to spray effectively. For every farm, it’s a unique size (and shape) depending on equipment and slopes but it is essential that you ‘prune to fit’.

When Jaff started here in 1994, he carried out an experiment/trial with regards to pruning. He invited his friends & neighbours, George Altona and Len Hobson, as well as another youngster who was telling everyone how to prune trees. He bought 3 new pairs of clippers, walked them all into an orchard – about 18 months old – and asked them to each prune a tree according to what they were advising. Three completely different outcomes, from three mac pruning experts. Jaff concluded that pruning young trees was unnecessary, especially if the experts deviated so drastically. “I’m not an advocate of pruning young trees – all I can say is that you mustn’t prune the bottom of young trees as all your crop is on the lower branches,” he summarises.

Excessive over-growth was one of the 10 items on Jaff’s list of possible issues behind his poor yield in 2020 and he has since put a lot of thought into this area and developed his own pruning protocol. He doesn’t believe that young trees require a central leader. Besides the fact that it’s not an easy directive to carry out when you have thousands of trees, he thinks the goal should be far simpler;

- keep the trees open enough to allow three things to get in; sunlight, air and sprays,

- stop growth that’s running away,

- cut in the joint, at an angle (to minimise witches’ brooms. Jaff has tried painting to prevent this but it didn’t work – all that happened was that the watershoots came out a little lower),

- keep lower branches.

The same principles apply to small and big trees. Trying to maintain a specific shape is not a part of his plan.

As this is a new area of focus for Jaff, he is applying the principles retrospectively, to his existing orchards and, by his own admission, it’s a messy affair. The orchards look like war-zones but he is exercising patience and executing the plan to ‘tame’ his mac orchards over 3 years. In year 1 the central leaders were removed. Year 2 & 3, the next tallest leaders, until the trees are under about 5m. This has left great big holes in the tree structure. “It’s not pretty,” he says, “but it’s completely necessary.” He knows because he has done this before, about 12 to 15 years ago, and it did the job. Unfortunately, yield over the next couple years will be negatively affected but it’ll bounce back, with interest, in the years after that.

All pruned material is chipped in the orchards, directly into a trailer, and moved to the compost pile/s.

A good illustration of lopsided tree, in the process of aggressive but gradual pruning. Next year, the leader responsible for the height will be removed.

Jaff is very cautious around the skirts – he’s done a lot of research on young trees specifically and says that, up until about year 6, 2/3 of the crop is in the bottom 1/3 of the tree. Logic leads us to conclude that the pattern doesn’t change much as the tree ages.

The ‘war-zone’.

When Jaff bought this farm, there were too many gaps in the mac orchards. The trees weren’t looking good and he was in a hurry to get into production so he added rows of Beaumonts (above). In hindsight, he says, this probably wasn’t the right thing to do. A hedger has been used here, just to try and open up the interrow but he says it is not the answer, it just serves to provide access. Next year this orchard will start the same 3-year ‘large leader removal process’ that the other orchards have been getting.

More war-zone.

Extensive pruning underway.

NUTRITION

It’s an interesting dynamic; having a team of experienced and strong farm managers, each with their own opinions and it’s inevitable that, on certain topics, there’s going to be differing views. Nutrition is one such subject in this operation currently. Jaff shares his viewpoint; “When mac prices increased suddenly everyone got a bakkie, put a sticker on it, and started selling fancy stuff to feed your trees. Prices have since crashed but everyone still thinks they should be continuing with the gimmicks. For example; for years, all we sprayed on flowers was copper, zinc and boron. Now they spray all sorts (four times, as opposed to the previous once). I’m just not seeing the correlating increase in yield to justify the expense.”

Jaff firmly believes that the roots are the engine room of the tree and require high grade fuel but he prefers a more ‘customised’ form of power; the NATURAL kind. He’s currently conducting a test in some weaker orchards to verify his belief that compost (addressing soil health) is the core solution. He’s drilling two holes on either side of the trees and filling them with 120 litres of compost. These ‘compost pots’ were inspired by observing how the tree behaved with the compost piles placed next to them (surface). When irrigation teams were out checking soil moisture and they used manual augers, it was often challenging to bore through the compost piles because they became so dense with roots. This told Jaff that the trees were vigorously feeding in the compost. The plan is now to continue with the sub-surface compost pots programme and replenish them every 5 years or so.

Jaff acknowledges that, without healthy soils, no amount of supplementation will generate meaningful results. He says that trees will struggle to take up nutrients from unhealthy soils. His advice to anyone starting this journey is to focus on making sure soil acidity is regulated and that carbon levels are elevated.

This farm makes about 5000 tonnes of compost every year and Jaff was quite willing to share the recipe: cattle manure, chicken litter from layers (this has egg shell content which increases calcium, and doesn’t have the sawdust that comes with broiler litter), macadamia husks (rich in potassium) and gypsum. This mixture is bulked up with wood chippings from pruning. They start building this up in March and end, after harvest, in August. They then start applying in September which means that it is not completely decomposed but Jaff says it’s good enough. He budgets on using around 7 tonnes per hectare. He used to EM (Effective Mirco Organisms) but Jaff believes there’s enough good stuff in the compost already. Even though the costs of putting compost down are high, Jaff sees the returns of having a healthy soil that will make untold nutrients available to the trees.

As mentioned at the beginning of this topic discussion, Jaff is not convinced that the fancy nutrition programmes they are currently running are necessary. “It’s expensive to drive a tractor through the orchard!! Not such a problem when prices were high but, at today’s prices, I’m questioning everything,” exclaims Jaff. And he’s found a tool that he believes will help him understand exactly what is required; brix testing. It’s something he’s doing in the avo orchards, on the flush that follows the flowers, and is using the results to decide what supplementation is required at this point. He’s currently refining the parameters and timing so that similar testing and decision-making can be done on the macs.

This pic shows us a few things; liming (which is always done before pruning), the compost mounds on either side of the tree and the dual micros on either side of the tree (to be changed to drippers).

One of the compost piles on the farm – this one is about 2500 cubic metres.

HARVESTING

Ethapon is sprayed on Beaumonts and on some other varieties, depending on the farm manager concerned’s personal preference. The only cultivar exempt is 791 because it flowers all the time. Jaff reports that ethapon seems to be working well on 816, but the dosage must be adjusted to avoid damaging the tree. They’re still working on refining this but want to get it right as Jaff knows that getting the nuts off the trees can only minimise stink bug damage. They used to harvest over 7 months but now aim to reduce that to 4 months. This retracted harvest period will also minimise losses to mould. “With prices at R50/kg we have to work smarter in every regard,” says Jaff wisely.

Jaff employs contract harvesters and pays per hour. The agreement stipulates the weight to be collected per hour so, essentially, it comes down to a per kilogramme cost. But harvesters can decide what hours they work. Jaff sends a tractor and trailer, fitted with a scale, through the orchards, and harvesters weigh their bags and pour out their nuts. Records on field, picker, weight, date, time are all extracted from this programme and used to analyse the crop as well as reconcile the weight recorded in field with the weight dropped into the hopper at the dehusking plant.

PRODUCTIVITY

Jaff benches 4 tonnes/hectare (dry in shell) as a realistic goal for a viable operation. In 2019 they averaged about 5 tonnes/hectare on producing orchards. One year on, it dropped by about a tonne. And then, in the subsequent year, plummeted to about 2t/h. While Jaff believes this dip was mostly climatic they also took a lot of corrective action in areas they can control; pruning, spraying (esp for dry flower) etc and this year, it’s picked up to about 3,5t/h.

I asked more about why he’s pegged climate as the culprit – this was the explanation; when a climatic incident occurs (like a scorching hot day or excessive moisture over a couple of days) the flowers/fruit will be susceptible in differing degrees, depending on their stage of development. Steep orchards often have a (about) 2 week spread of development from the top of the orchard to the bottom. Jaff reached this conclusion by closely inspecting these steeper orchards 4 to 6 weeks after a climatic incident. What he saw was that there were ‘bands’ of affected produce ie: the flowers at the top may have been too under-developed to have been affected and the flowers lower down might have been set already but the ‘band’ in the middle was in full flower (most delicate) and therefore most susceptible; the yield here will be lower than above and below. As the entire orchard was farmed exactly the same, only one factor would be different – stage of development (and the consequent susceptibility to the climatic condition experienced). Which means that climate adversely affected PART of this orchard, depending on the stage of development when the abnormal weather occurred. Remember that weather also affects insect activity and therefore pollination. Because we are seeing more and more of these “exceptional” days, climatically, yield is threatened more and more. Jaff is convinced that, in 2020, he got (especially) unlucky.

PROCESSING

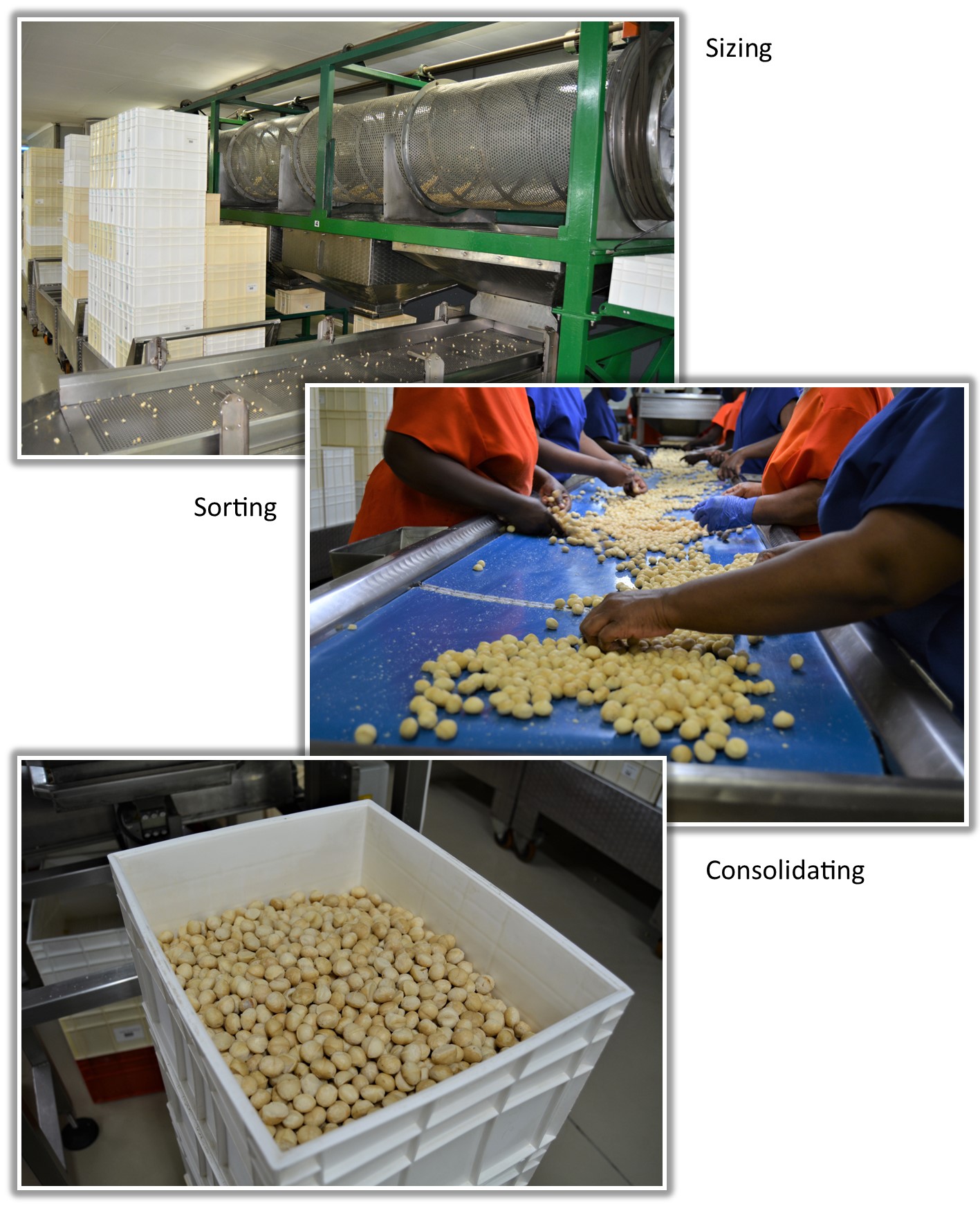

As mentioned, Jaff is an owner of the local processing facility. This interest adds an invaluable insight into marketing that drives what Jaff plants. Some farmers plant what works on their farm. Here, Jaff adds to that by planting what the market wants.

Jaff kindly connected me with his factory manager who very kindly took me through the plant and shared his insight into processing and marketing.

He explained that it’s a macadamia marketing is a tough environment with competition between the processors a little too elevated for his comfort. He’s recently spent some time living and working internationally and shares how he thinks a little more collaboration and cooperation would benefit the whole industry. He also acknowledges that perhaps this factory is just a unique ‘being’ in that the 3 shareholders are all farmers whose main objective is to get the best price, back on farm, for them and any other farmers who use their services. Profit is reinvested in the operation.

In 2021, when China was still buying nut-in-shell, the factory cracked just over 1600t, wet-in-shell (WIS). This year, they’ve already done over 2100t (WIS) and are nowhere close to being finished … “it’s going to be a long season,” (sigh). The expectation is that they’ll finish off around 3500t.

The plans to cope with these volumes going forward is to work 24 hours and install a colour sorter (that has already been secured for 300k Euros!!!). This business has always had a preference for people-power rather than over-automating everything, in the interests of reducing unemployment, but they are now at a point where they can put in a colour sorter without sacrificing jobs – although it will require some people adjusting to night-shift life.

There is a drying capacity of just over 700 tonnes. They operate on a simple ‘no risk, no reward’ basis with farmers being paid when the nuts are sold and paid for. Most of their kernel goes to USA and Canada.

Here are a few other points of interest around marketing macs:

- USA imported 13% more macs this year than last year, at a 12% lower price, but the price on the shelf is 5% higher than last year. Not sure about you but my mind slid off the tracks after the second stat in that report … Basically, what has happened is that there is still stock in the system, with the old (higher) cost price. Retailers need to move that before they can lower the price. Higher prices = slower sales. Apparently, it will take about 18 months to work these old prices out of the system and therefore the same time before volumes start increasing in response to lower prices …

- Shipping costs are exorbitant; last year a container cost around R80k. This year it’s between R170-190k/container. As usual, farmers are the ones who lose out and now need to chase volume in order to realise the margins necessary to remain viable.

- The World Macadamia Organisation (WMO) is currently focussed on creating demand in China and India, as well as in the vegan space globally.

- There is a 30% levy imposed on South African macadamias exported to India. Australians have just negotiated free trade with India so hopefully more of their nuts will go there and open up other markets for SA nuts.

- China has a 14% levy on South African nuts but, again, nothing on nuts imported from Australia which is understandably frustrating for marketers but SAMAC is work on addressing issues like this.

- Kenya is becoming a big player in the mac game. Their quality is improving and they have lower minimum wages giving them a competitive advantage. They are often encountered on the global stage and are usually very hard to compete with.

The advice for mac farmers is to avoid Beaumonts and 791 cultivars in any planned developments; the Beaumonts are prone to breaking into pieces during cracking and the 791 spot is becoming more of a challenge to sell as buyers become fussier. The advice would be to increase on varieties that produce larger nuts of better quality, like A4 and 816 as there are far more markets open to this produce.

Here’s a pictorial walk through Jaff’s facility:

Some pics from inside the pristine processing plant owned (in part) by Jaff.

And there ended my fascinating and uber-insightful day in Jaff 27’s world. Exhausted, I retreat to the B&B to start penning this story. I hope it has spawned your Celebration Beast and that he’s been well-nourished by this epic Jaff’s success.

Keep him fed until the next TropicalBytes Jaff story!