| FARM CONTEXT | |

| Date of visit | 8 April 2021 |

| Area | Robertson, Western Cape |

| Soils | Mostly weathered shale and sedimentary rock |

| Rainfall | 400mm annually |

| Altitude | 300m |

| Distance from the coast | 110kms |

| Hectares under mac | 23 hectares |

| Varieties | 788 – 15ha. A4 – 2,5 hectares. 814 – 1 hectare. 791 & Beaumonts make up the balance |

| Other crops | 2,5 hectares apricots |

It’s Thursday of my week in the Cape. Three interviews down, two to go. But this Jaff is all the way out in Robertson – the most western macadamia farmer in our country, unless you count the one who is giving it a (good) go in Vredendal. Roberston is 3 hours away from George (where I am based for the week), that means a 6-hour round trip PLUS interview time … I’ve got to be honest, I seriously considered cancelling. Jaff even seemed to be discouraging me by explaining that he is a very small, practically-retired farmer. Oh boy … was I going to waste some serious time and fuel?

Robertson – crazy that macs are now thriving this far west.

But then, when I mentioned I was going out to see this Jaff, someone asked “Is he still alive!?” … now, for me, the longer you’ve walked this earth, the more I want to meet you – such experienced souls are gold-mines of rich information and valuable life-experience. When I found out Oom* Jaff was 84 years old, I knew I was going to Robertson! (*for international readers, Oom means Uncle but it is also a term given as a sign of respect for male elders, regardless of their relationship to you.)

This view across the farm was worth a 1000kms!

But I must thank the good Lord for Kobus, the local Green Farms support guy. He not only convinced Oom Jaff to spend time with me, he also drove me all the way out there. Thanks again Kobus – you are awesome and appreciated! And Oom Jaff turned out to be a legend. He’s practically royalty in the macadamia industry and I am so grateful I made the trip!

Oom was full of wonderful stories and this one kicked us off … one day a mom was cooking a roast. She cut the four edges off which left a square piece of meat. Her daughter, who was watching and learning, asked, “Mom, why do you cut the sides like that?” Mom replied, “I don’t know, it’s what my mom always did, we’ll have to ask her.” The next time they saw Granny they asked her. The reply was, “My roasting pan was too small.” Although funny, I found it quite profound in that many farmers, especially those whose families have been in farming for generations, are doing the same things their parents did, without questioning …

Oom was farming in Tzaneen, on a very large scale! He’s now retired and farming on what he considers to “hobby-scale” – 30 hectares. He explains that what others still have to learn, he’s already forgotten. He also informs me that if I ask a question and he takes a while to respond, he’s just consulting his internal Google and sometimes the service is a bit slow! Yes, his head probably rivals Google with resource material! If only we all had access to this ‘internal Google’ of his but I’ll do my best to wring what I can out of it.

Oom started commercial life as an industrial chemist. He then went into photographic and electronic retail in Walvis Bay. At this point I stop him (already ) … “but aren’t you Oom B’s brother? From that prominent mac farming family?” Oom explains that his brother inherited the whole family farm in Levubu meaning Oom had to carve his own path in life. Only in 1978 did he decide that he’d like to get back into farming.

Oom and his beautiful wife (she’s too youthful to call “Tannie”) bought a farm in Polokwane where they grew granadillas for a while. Oom then decided that avos were the thing to do but their farm wasn’t right for that crop so they bought another farm between Tzaneen and Duiwelskloof where they began a journey with avos. After a few years this highly perishable commodity lost his interest and he looked around for something a little less fragile. The macs his brother had been working with were the answer and in 1985 he started mac farming.

Hail storms were no longer the heart-stopping experiences they used to be … picking, packing, storing and shipping were also far easier with macadamias than they had been with avocados. And there was time – gone was the panic caused by the highly perishable avos.

They ended up with 83 hectares of macs in total, the youngest of which were only 4 years old when they eventually sold the farm. The sale was motivated by the increasing threat of land claims in that area. They’d always loved the Cape and decided to look for something within 150km of Cape Town. In 2005, the search turned up this 156-hectare property, which fulfilled all the requirements. The existing operation was dairy, vineyard and some stone-fruit trees. As most of the property is this spectacular mountain (pictured below) only 30, of the 156 hectares, are arable but Oom knew that it was perfect for his retirement-sized farming plans.

To keep himself busy, Oom thought he’d see how macs did in the Cape and so he squeezed some trees from the nursery onto the furniture removal truck before it left Tzaneen. These became the trial orchard on the new farm. They grew, flowered, set and flourished. In the meantime, they had a disastrous experience with pomegranates and were very relieved to be able to turn their attention completely to the thriving macs.

Right now there are 23 hectares of macs on this farm – which most of us would consider a little more than a hobby, especially when you’re an octogenarian!

Oom had a wonderful way of communicating things without jargon. When I asked about the soil, he gave a response I could really understand, without the scientific terms. He explained that the soil here is weathered shale and sedimentary rock. Not particularly hard. A few centuries ago, he might have had a slate mine but it has deteriorated past that now. There’s also a lot of sand and a little red soil – coming from (iron-rich) deteriorated dolorite. All the soils are well-drained. Kobus adds that this is one of the few Cape farms that is so well-drained – most are situated on very shallow clays and struggle with water-logging. When I ask about the soil depth here, Oom points to the blue gums and teaches me that whenever you see these trees in a mature state, you know the soils are deep. Despite the depth, these soils are vastly poorer than what Oom was used to working with. In Tzaneen they had deep, rich reds and rarely saw a single stone. Here, is sometimes seems like there’s nothing but stones.

To my untrained eyes this soil looked horrible but Oom was not phased – he has found how to work with it.

Understanding Climate

Climatology is an interesting topic and Oom has enjoyed learning about this environment and to farm in it. He taught me about how “berg” winds form – here in the Cape it happens when very cold air comes off the Karoo and rushes down the mountains towards the coast. Anything under pressure, that moves fast, generates heat and air is no different. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Adiabatic_process#:~:text=Adiabatic%20heating%20occurs%20when%20the,compared%20with%20t he%20compression%20time

In KZN the same phenomena is experienced when the cold air comes off the Drakensberg and rushes seaward.

Whilst it is important to know what the climate is, it is equally important to understand how much it changes – in other words, it shouldn’t be a considered too great a limiting factor in farming. Oom says that once the mac trees grow to full size, they create their own climate in the orchard.

Water

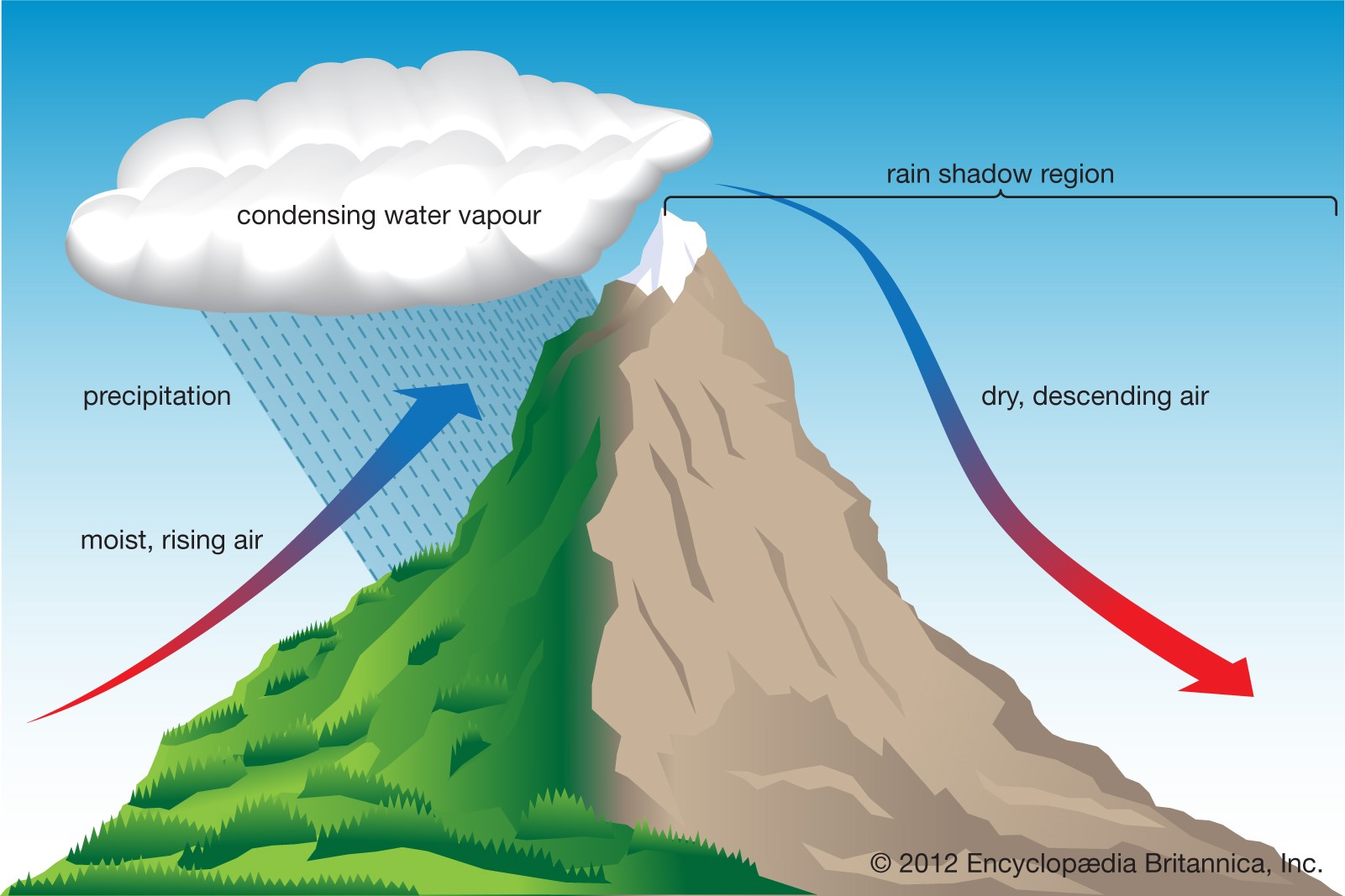

The rainfall here is orographic (new for you too?) Oom explains that the south-easter, loaded with moist air, is lifted by the mountain range. The air then cools, clouds form and rain falls. There is very little thunder and only about 400mm of rain falls on the arable land annually. To take full advantage of the precipitation at the higher altitudes, there is a water scheme up in the mountains. To supplement this, he has also drilled boreholes. 2,5kms of cable had to be laid so that he could move this water. A fourth water source; the local dam, completes the quartet. Having the various catchments mean that these mac trees can be irrigated all year round.

Orographic rainfall.

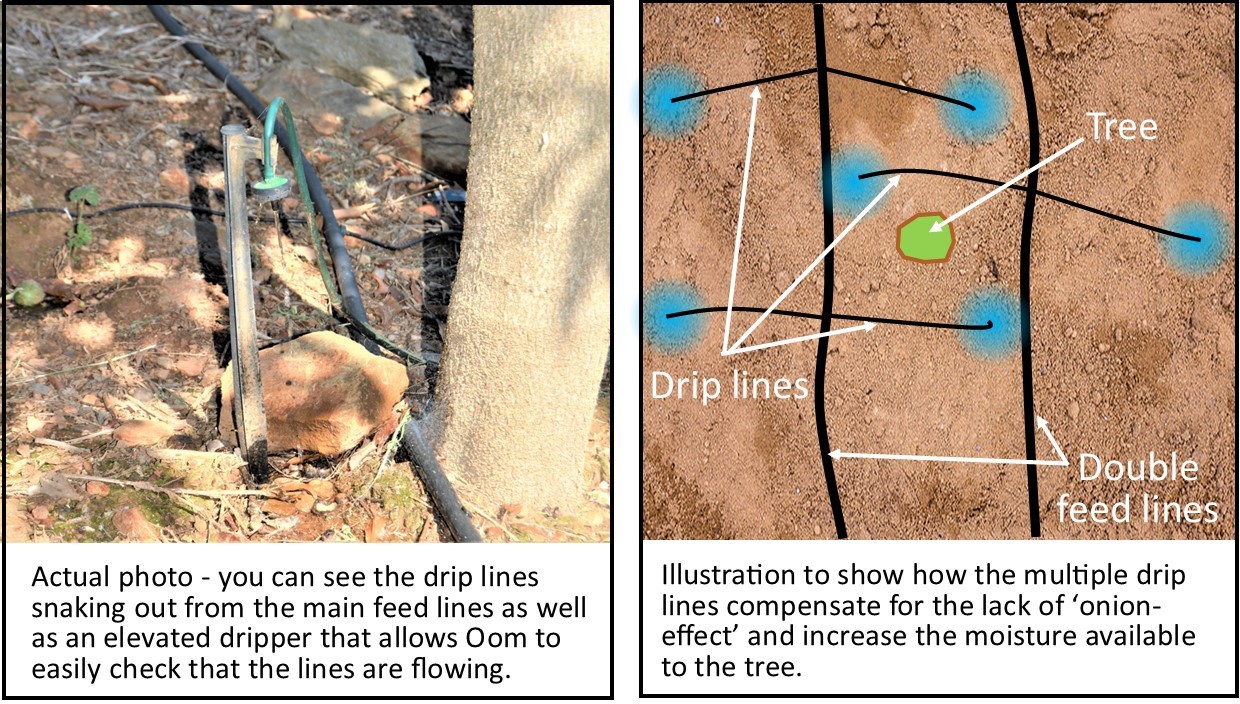

The whole irrigation system here has had to be carefully thought out; microjets use too much water and drip irrigation is not suited to the sandy soil as the “onion effect” doesn’t work in these soils. I know that most of you are familiar with what this is, but indulge me as I share with anyone who hasn’t come across this term …

As you can see, the fact that sandy soils drain too well makes conventional drip irrigation ineffective. This left Oom with a problem as rainfall is too low to use granular fertilisers … he decided instead to level-up the drip irrigation option. He did this by running double feed lines and placing multiple drippers around each tree.

He uses soluble fertiliser through this drip irrigation system.

The water here is a bit alkaline. To balance this, he adds nitric acid which lowers the pH.

The soil has a very high calcitic composition.

Oom confirms a well-known mac-fact; that the whole Protea family (of which macs are a part) is very sensitive to phosphates, although they still need them. Any phosphate applications have to be done cautiously. In the Lowveld, Oom used acetic acid soluble phosphates because the soil pH was lower there. Ordinarily, water-soluble phosphates would be used.

Another confirmation of a growing movement is that irrigating macs needs to be a slow and consistent activity. He warns that over-irrigation just leaches fertiliser. He suggests instead that we irrigate less, more often. Here, he cycles on a 3-day programme. Each tree gets about an hour (50 litres) through an average of 4 x 8l drippers. Every farm is unique and he has chosen this configuration because of his specific infrastructure, on this farm, is limited by a lack of pressure.

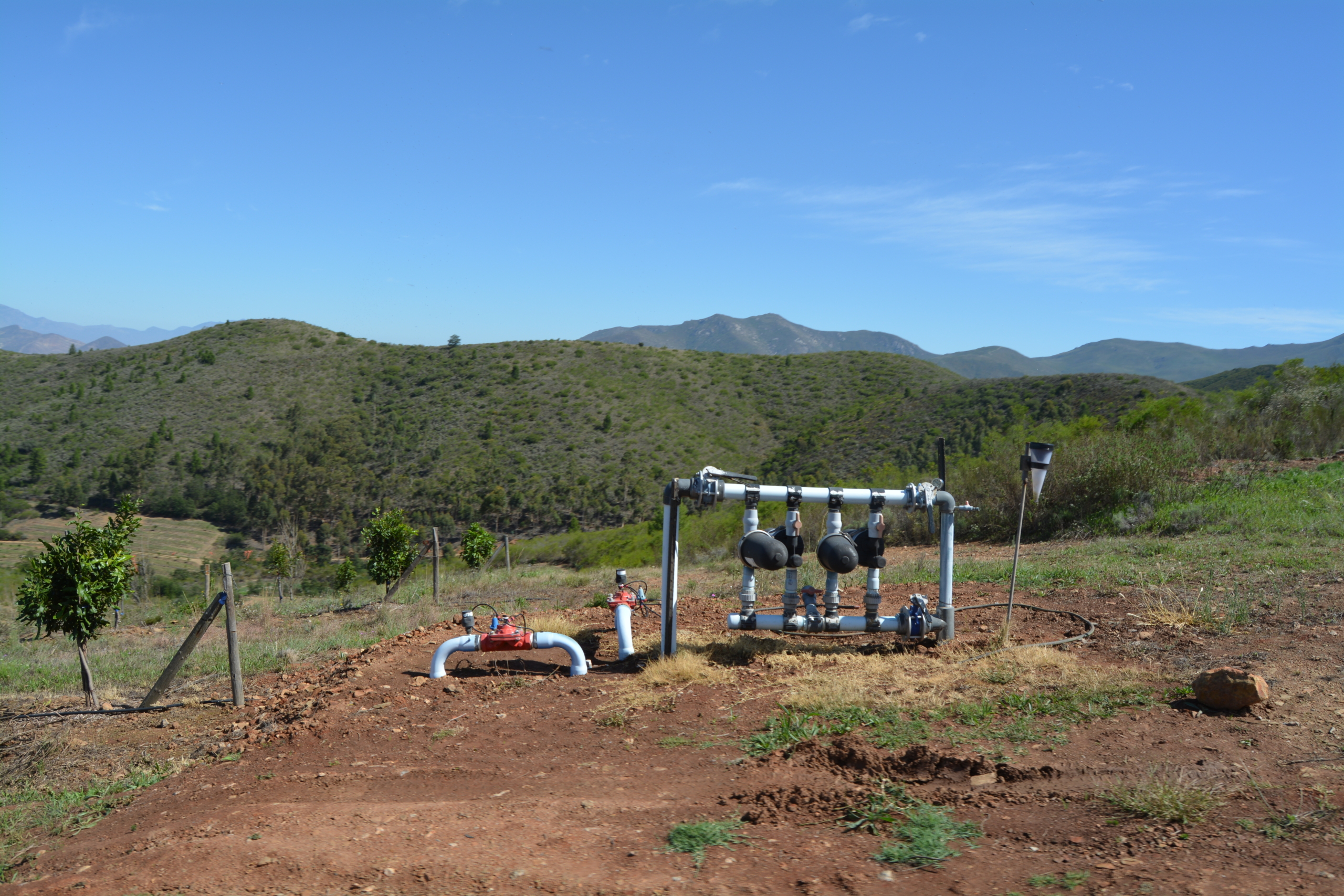

Part of the irrigation scheme, all designed, built and maintained by Oom.

All Oom’s irrigation is gravity fed. Water from the scheme and from the boreholes goes into a reservoir and from there the system is manually operated. He also does all the maintenance of the irrigation infrastructure, all the grass slashing, fertilising and all the herbiciding. He only has 3 workers to assist him on the farm; they do grafting, staking, wires (explained under ‘Pests’), and composting.

The view from the reservoir platform.

Fertilisers

The majority of nutrients are applied through the fertigation system, including NPK. The only other method used is foliar sprays.

Ammonium sulphate, which is an acidic fertiliser, is applied every 3 weeks. This also helps to lower soil pH. The dosage is 15kgs per 400 trees. Then, from time to time, Oom adds trace elements like molybdenum, manganese, a little magnesium, iron and zinc and copper. All of these are sulphate compounds because that minimises reactions with other chemicals.

Oom explains that he would not add any calcium because calcium reacts with sulphates and precipitates. This is why he uses all those trace elements with ammonium sulphate as the nitrogen source. Phosphates are never a part of that mixture. These are added in the form of MAP to ammonium sulphate.

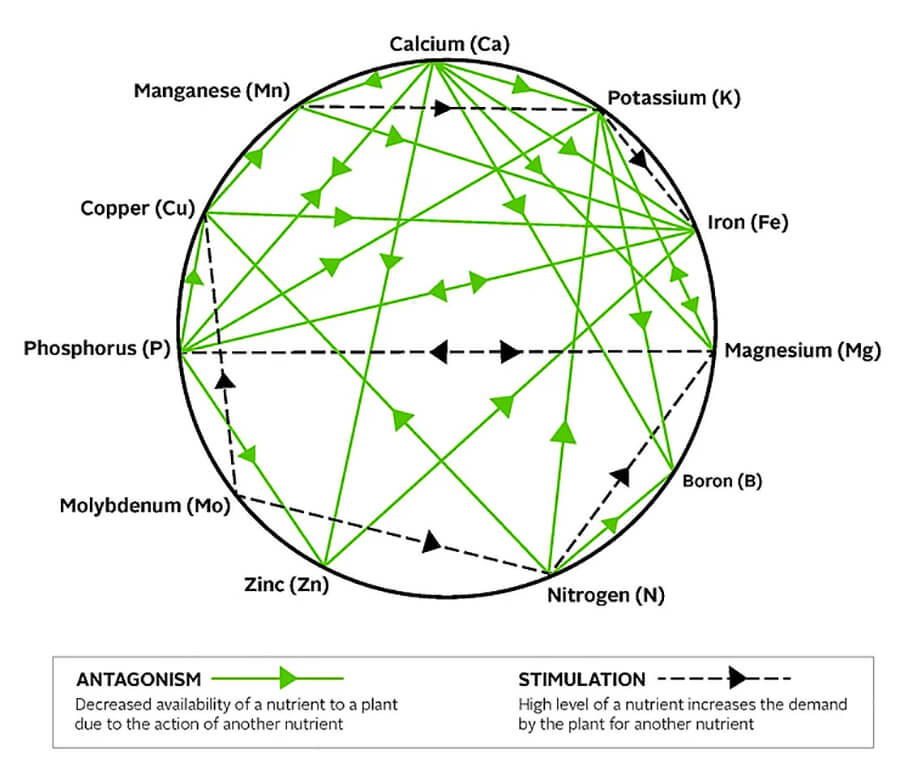

Given his chemistry background, Oom is obviously very insightful about soil nutrient availability and I used a lot of this information in the soil article https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2021-9-soil/ but one of the most interesting pieces was the concept of antagonistic availability …

Antagonism: High levels of a particular nutrient in the soil can interfere with the availability and uptake of other nutrients. For example, high nitrogen levels can reduce the availability of boron, potash and copper; high phosphate levels can influence the uptake of iron, calcium, potash, copper and zinc; high potash levels can reduce the availability of magnesium. Thus, the application of high levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK) can induce plant deficiencies of other essential elements.

Stimulation: This occurs when the high level of a particular nutrient increases the demand by the plant for another nutrient. For example, increased nitrogen levels create a demand for more magnesium.

When mac growth is making feather dusters (a small tuft of leaves on the end of long, bare branches) Oom explains that they need trace elements. If new leaves are small, then they need zinc – a common deficiency in this area. Long ago, this area was struggling with poor wheat yields – they discovered that the soil is short on copper which is very important for cell formation. To address this, Oom adds copper sulphate. Interestingly, age affects our (human) ability to assimilate copper into our bodies and one of the outcomes is grey hair. Perhaps this extensive knowledge of minerals is the secret behind Oom’s incredible health? He says he never eats braai meat because meat cooked at high temperatures turns the fats into dangerous chemicals which are carcinogenic.

I struggled to keep up as Oom spouted tips and advice on a myriad of supplements but here’s a summary of the micro-nutrients used:

- boron (as boric acid) and zinc just before flowers open.

- Copper sulphate in flowering season.

- Potassium silicate just before fruit set. Potassium for fruit growth, silicon for strength. Potassium silicate is also an anti-fungal on flowers. It is very alkaline and cannot be mixed with other components.

- He also adds a little potassium nitrate (which stimulates growth) and fulvic acid to the flower spray. The fulvic acid is the organic additive that will make the inorganic potassium available to the tree. To flower, plants need potassium. When I pressed for an exact timing of this spray, he explained that it is just before the nut drop phase which is November in KZN. Further north, it would need to be earlier.

- magnesium and iron is important for chlorophyll.

- Phosphorous is important for root development but too much will prevent iron from being absorbed. This is called iron-chlorosis which is a lack of iron even if it’s there.

- Calcium nitrate is something that Oom will apply through the irrigation but he will also spray it on the fruit, once it has set because cell formation requires calcitic lime. This lesson was learnt in the apple and peach market where fruit was going brown in the inside (biterpit) because of a lack of calcium. In those days, they used to spray calcium-arsenate but have since changed to a special preparation of calcium that excludes arsenic. Oom sprays calcium with folvic acid which is also good for cell formation. He explains that what happens if there is not enough water and hydraulic movement from the ground, then the fruit does not get the nutrients it needs. He adds boron as well because it is a mobiliser. Calcium and boron work together on all growth tips.

This farm is about as picturesque as I have ever visited.

For the more established orchards, he uses a tractor-mounted mist blower while, for the smaller trees, he uses a hand-lancer.

One final tip on nutrition was to avoid using nitrogen before flowering. This is because it will stimulate the tree to put energy into vegetative growth rather than reproductive growth. The right activity to stimulate at this time is flower induction. Oom stops nitrogen and limits water from a few months before flowering season.

Soil health

Key to soil health is water ph which needs to be around 6,5. Oom says soil samples are also very important. Although occasional leaf samples would also be good, Oom works mostly by intuition in this department. A leaf analysis report tells you what plant has. But, by looking at the leaves you can tell what the plant is lacking.

Compost is a necessity, especially in this sandy soil. Oom uses mostly chipped prunings from the orchards and wild trees. He says the decomposition process can be accelerated by adding an EM mix (effective micro-organisms). This he also adds to the irrigation wateer from time to time to keep soil microbes happy. To make EM, he has a 1000l tank with a circulating pump. To the water he adds 20l molasses plus 2l EM (which you can buy from most agri shops in buckets). This is circulated for a period before being applied.

Currently mulching is only done on the newly planted trees but he plans to extend it to the bigger trees as well.

One of the maturing compost piles.

Sprays

Unlike KZN, in Robertson the summers are hot and dry and the rains come in winter. Temperatures rarely exceed 30°C and there is no frost. Snow can come as early as May. Humidity levels in this region are relatively low, hovering around 30 to 40%. This opened an interesting discussion as I have always understood that macs thrive in highly humid conditions. Oom reminded me that this excludes flowering time when high humidity can be a killer as it encourages fungi. That’s not a problem here and Oom declares that he sprays nothing … silence … sorry, did you say that you spray nothing? What about stink bugs and moths and thrips? Nope – nothing! The only sprays that happen here are micro-nutrients.

Oom encourages bees on the farm but has to keep the hives out of the reach of honey badgers.

Pests

Oom is fairly isolated (from other mac farmers) in this valley. Between that and the fact that the winters are very cool, he is not struggling with insects for now. But he knows that to practice mono-culture is to invite insect problems so he’s not saying he won’t face challenges in years to come.

For now, the only real pests are mammalian – for the last 3 years they’ve had issues with bushpigs and he thinks the baboons will become a problem when they taste the macs, which they haven’t yet. Right now they prefer to feast on Oom’s prickly pears, quinces and figs and they also stripped his pecan nuts last year. These apes haven’t yet developed a palate for the apricots, luckily, but the time will come.

This is an A4 with the lower, bearing branches tied up so that the bush pigs can’t get to the nuts. It has also helped limit wind damage while there’s a crop on the tree. But look at the size of those nuts!!

If you do have stink bug issues, Oom recommends bat houses as these nimble creatures can eat up 80 stink bugs a night, each.

He has noticed what might be an early stink bug sting on the small nuts so it isn’t normal stink bug damage but the full-grown nut is malformed. There is some mealybug on some of the trees, which does not cause any damage but Oom still doesn’t like it. The ants, on the other hand, are a challenge. To deal with this, he mixes mielie meal, sugar, borox and Regent (active ingredient; fipronil which is used for flea control on cats) – this mixture is sprinkled under the tree. The ants collect it and take it to the queen, who is poisoned and dies. Another variation of this effective remedy is to mix fipronil with some molasses and spray it on the tree trunk. The ants and the mealybugs have a symbiotic relationship so controlling the ant problem usually sorts the mealybugs out too.

Oom reports that there are no other pests here at all – no thrips, aphids or moths. When he had pomegranates they had terrible FCM problems but these moths don’t seem to have figured the nuts out yet.

This tree was sick (pic on left) The pic on the right is the same tree, after some time and KH2PO3.

When it comes to phytophthora, potassium dihydrogen phosphite (KH2PO3) is used. This is a root stimulant as well as an anti-fungus; an available source of phosphates (PO4) only when the tree wants it. PO3 is not an available phosphorous source for the trees but microbiomes can convert it to PO4 which can be taken up as fertiliser by the trees. The key ingredient here is healthy soil life but Oom says, if you have that, the KH2PO3 works like a charm and he puts it in the irrigation water if there’s any sign of phytophthora.

In line with the growing national trend, theft by humans is an issue on this farm and Oom’s son has rigged a series of cameras on the property to provide early warning and evidence.

Cultivars

On this farm, there is 788, A4, 814, 791 and Beaumont. Below are Oom’s views on each of these varieties:

788:

- Oom’s favourite cultivar

- Thick husk which Oom feels helps against stink bug damage

- Thin shell which gives great crack out results

- Sets very well; less flowers than a Beaumont, but more nuts.

- Smooth leaves, very similar to but darker than 814

816 on left 788 on right – both 3 years old

A4:

- Oom’s second favourite

- A very willowy specimen

- Bears HUGE nuts

- This is a tetraphylla and Oom advises that they should be planted in separate orchard blocks to integrifolias (814, 814, 788 etc) so that they are not mixed in harvesting and thereby kept separate through processing where they require different roasting procedures.

Beaumont:

- A no-no in Oom’s book because he says they were originally selected as an ornamental tree; beautiful in the garden because of their prolific pink flowers but there are a few issues one should be aware of before expecting them to deliver commercially:

- They do not drop their nuts naturally like other cultivars

- The flowers are very prone to blossom blight

- They are late bearers which means there is very small window for pruning before the next flowering comes in.

- Multiple flowering are triggered by the cooler Cape weather

- Despite all that, they do make a great root stock

Impressively laden Beaumont

791:

- A precocious bearer (bears young)

- Good pollinator

- Also a very willowy tree

- Tends to be an out-of-season bearer

Nelmak 2:

- Gives ONE, in-season crop (as opposed to the multiple given by Beaumont and 791)

- Also a tetraphylla

814:

- Smooth leaves, easily confused with 788 whose leaves are also smooth but slightly darker

- Produces many nuts but they are small. This is good for the Japanese market because Japanese women don’t like to open their mouths wide. Australia has a lot of that market currently.

Oom’s favourite child – 788

Oom’s summary advise on cultivar selection; “ Depending on the size of the operation, select cultivars that will give you a wide window of harvesting.”

Planting

Because of the deep, sandy soils, no drainage was built into the orchards. The land prep consisted of one rip. Lime also wasn’t necessary as a rule because of the high calcium levels of the soil.

When Oom planted macs into what were the vineyards he did not remove the fencing poles and wires that were used to suspend the vines. He uses those to stake the young trees, as seen in the pic below. Additional stakes were added for extra support. The trees remain staked for 4 years.

In these orchards a 5m x 3m spacing was used but ordinarily Oom goes for 6m x 4m and does not remove trees as they mature.

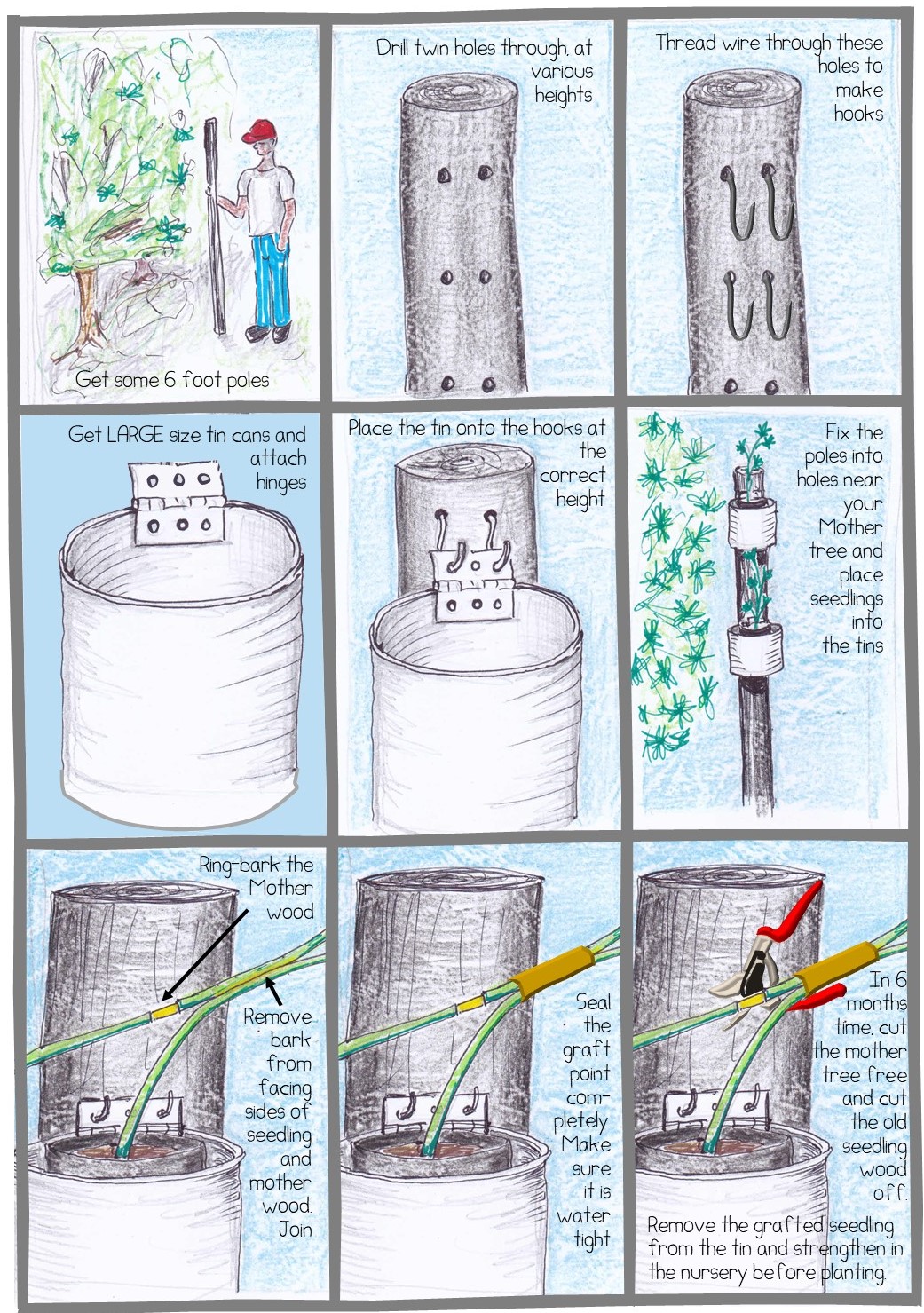

He plants seedlings (either 788 or Beaumont) directly into the orchard and then grafts later, when they are about 3 years old. He uses two methods; either 3 to 4 wedge grafts (as discussed in Jaff 17’s story https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/2021-07_jaff_17/ ) or approach-grafts.

Approach grafting is not common but Oom has used this method a lot and reports a 100% success rate. It requires a separate irrigation system into the field but is much quicker than block grafts as the budwood has a constant supply of energy from the mother and from the seedling. This means that 12 months can be cut off the process. It does require careful planning and a supply of ready seedlings.

The process is described in the graphic below:

Thank you to Barry Christie from Green Farms for this gorgeous picture that shows the Langeberg mountains covered in snow AND the approach graft technique in action. The trees are A4.

Oom runs a very neat and well-managed nursery, complete with an effective (and soon to be automated) overhead irrigation system. All seedlings are either 788 or Beaumont. Oom prefers using his own nursery because the plants are all fully acclimatised when they go into the field.

Small, but neat and efficient, nursery.

Chinese poplars are used as wind-breaks

When Oom plants, he first spreads lime (if necessary) and then rips. After that a small hole is prepared, and a little bonemeal together with a lot of compost is added. The trees roots are cut if they need loosening. He then adds boric acid so that it’s mobilising properties assist in getting nutrients to the new tree. After planting the tree gets a manual drench of very diluted potassium dihydrogen phosphite (KH2PO3) and Kelp (seawees extract).

Once the seedling is established and strong (about 2-3 years later) he will top-work it with whatever cultivar he is after. Generally, two years after that, he has a crop!

Pruning

Oom explains that the objective of his pruning is to enable air circulation and sunlight access. This, in turn, will encourage fruit set. He aims for a conical-shaped tree focussing most of his attention on the outsides of the tree but, every now and then, he removes an inside branch. The trees here grow to about half the height that they did in Tzaneen but he still controls vertical growth because they harvest by hand. No nuts are allowed to fall on the ground as they will be lost to the bushpigs. As soon as the inside of the husk darkens, harvest opens.

Oom has the most incredible tool that he uses for pruning; a cherry picker. There is a hand-held hydraulic saw fitted to this vehicle. He bought this from Israel in the early 1990s and it has been a solid investment, being the perfect solution to many jobs around the farm. It powers itself, freeing up the tractors for other tasks. The brakes work off the hydraulics.

Harvest

Harvesting only starts in May or June and this “small” farm’s results are impressive with an average of 4 tonnes/hectare (DIS) and an average SKR of 30%. Currently this yield is predominantly from the 788s and Beaumonts as the other trees are too young to make a contribution just yet.

Processing

Oom describes his current processing set-up as “Heath Robinson” but it works for the volume he has now and there are plans afoot for an improved facility.

This is the view from the platform that has been cut for the new dehusking shed.

He always makes sure that nuts are dehusked within 24 hours of harvesting and the 788s are kept separately so that, when they go to the processing plant, the deshelling equipment can be adjusted. If it isn’t, his very thin-shelled nuts are bruised and damaged.

Currently this old tobacco drier is used to dry the nuts.

Privilege

I honestly consider it a privilege to have spent time with Oom and to have had him share not only his wisdom on farming macadamias but also on life in general. Here are 5 things that stuck with me:

- Acceptance with contingencies: There are things you can control and there are things you can’t control. Focus on those within your control and create contingencies for those you can’t.

- Never give up: You don’t have to do everything in one day – just consistently do something. Keep at it and you will succeed.

- You need the good as much as the bad: Homeostasis is an equilibrium. You have to experience more than that to grow. Use the “downs” as a reference for your “ups” and visa versa. Ie: to know great joy, you need to have experienced great sorrow. To really value great success, you need to have failed – spectacularly.

- Mistakes are essential. It’s how we learn everything.

- No limits: We have potential to do ANYTHING. Intelligence is supressed mostly by one’s OWN nature.

I am still in disbelief that this exceptional farm is run by an 84-year-old man, his beautiful, supportive wife and 3 labourers. It is inspirational and motivational. Thank you Oom for the magical day and the profound learnings. And to you Kobus, for not only paving the way but for actually taking me there too!

Bibliography

https://www.britannica.com/science/orographic-precipitation

Simply perfect!