A commitment to bringing you insights from the very best in the industry, necessitates travel – a LOT of travel. So I decided to do it all at once; 30 interviews, 2500kms, two weeks on the road. All with the aim of delivering the 12 VERY BEST stories for you this year.

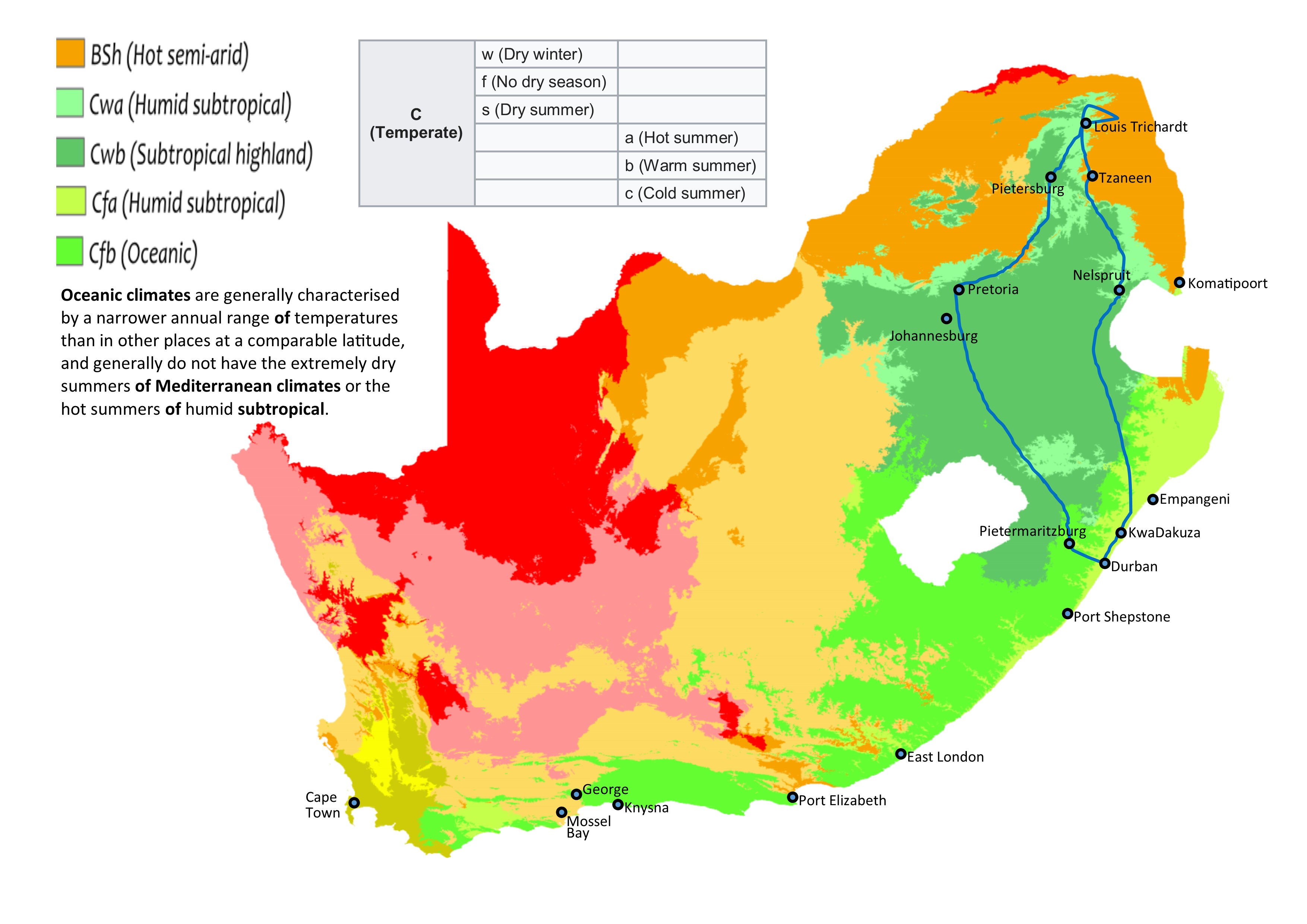

The thin blue line shows the route I took. I have transposed it onto a climatic map as it is interesting to see the different regions – the oldest mac growing area is far north, in the “dry winter, hot summer” region but the macs seem to be performing best in the “no dry season, warm summer” region, further south, although both are classified as Humid subtropical.

This trip allowed me the opportunity to gather content for most of this year’s topics:

January – Already published – Mac Varieties, Characteristics

February – you’ve already enjoyed this story on Jaff 8, from Kearney near KwaDukuza

March – History and Overview of Mac farming in SA (this article)

April – Moisture (Water) Management

May – Training (Pruning)

June – (in the beginning) Nurseries

July – Soil

August – Nutrition

September – Pests

October – Jaff 9

November – Jaff 10

December – Beyond our borders

The one you are about to get into was going to be an article on Processing but I learnt, quite early in the trip, that this is quite a prickly sector. The industry is young, passionate and growing exponentially so I suppose it stands to reason that there is some jostling going on while everyone finds their places and settles into the long term. While that happens, I am happy to bring you an overview of the industry and a look back at the history.

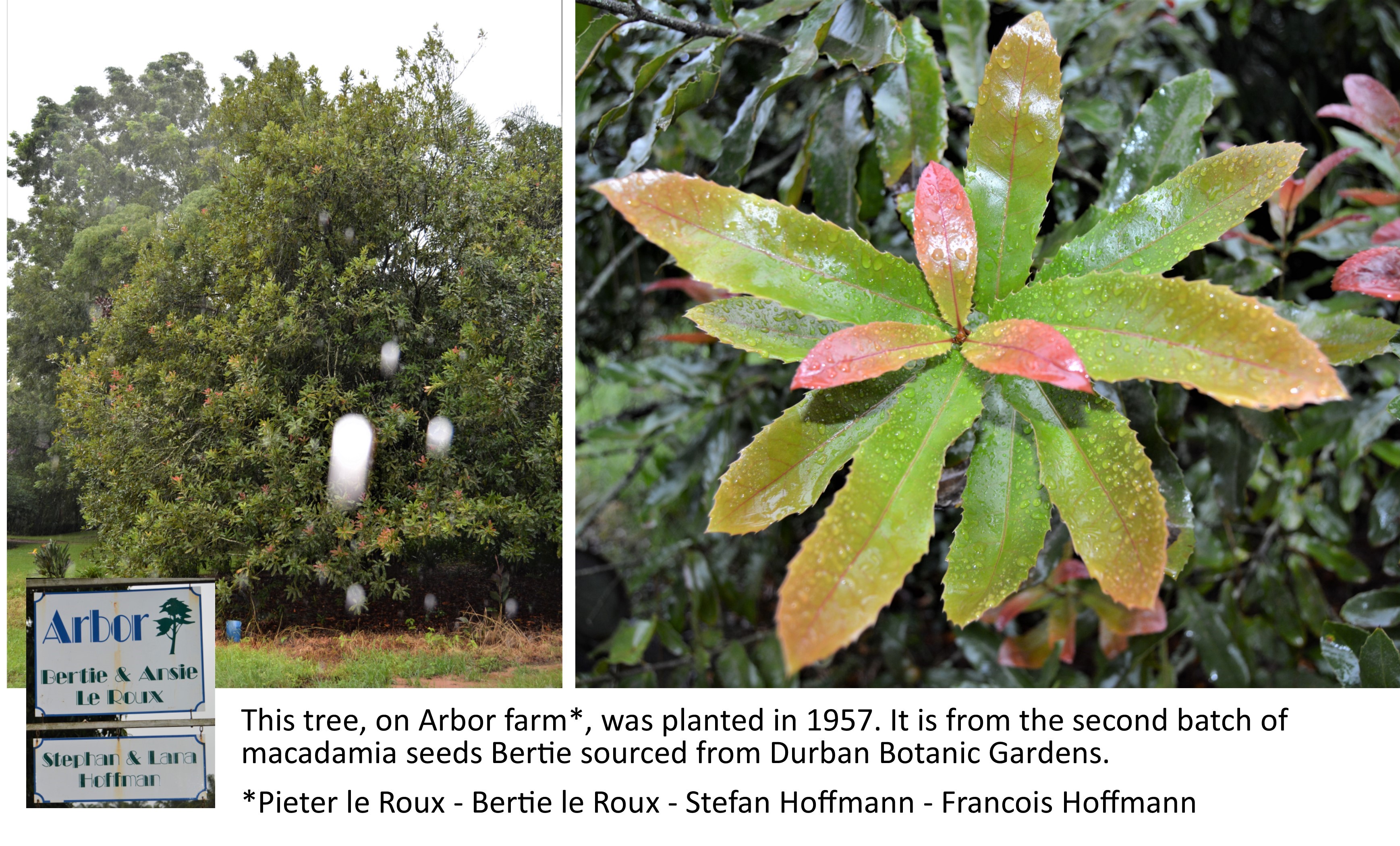

You spend time investigating and getting familiar with an industry, travelling and meeting new people and then, suddenly, you realise you’ve found the epicentre. The place it all began. There was an immense sense of wonderment when this dawned on me, in Levubu. I wasn’t looking for the core, I was just doing what I always do – looking for the best. But, when I met one of the grandmothers of the industry, in the form of a 63-year-old mac tree, I knew that this was where it all began.

I happened to choose the wettest week Levubu has had in forever – 400mm of rain! So, please forgive those raindrops on the tree picture above.

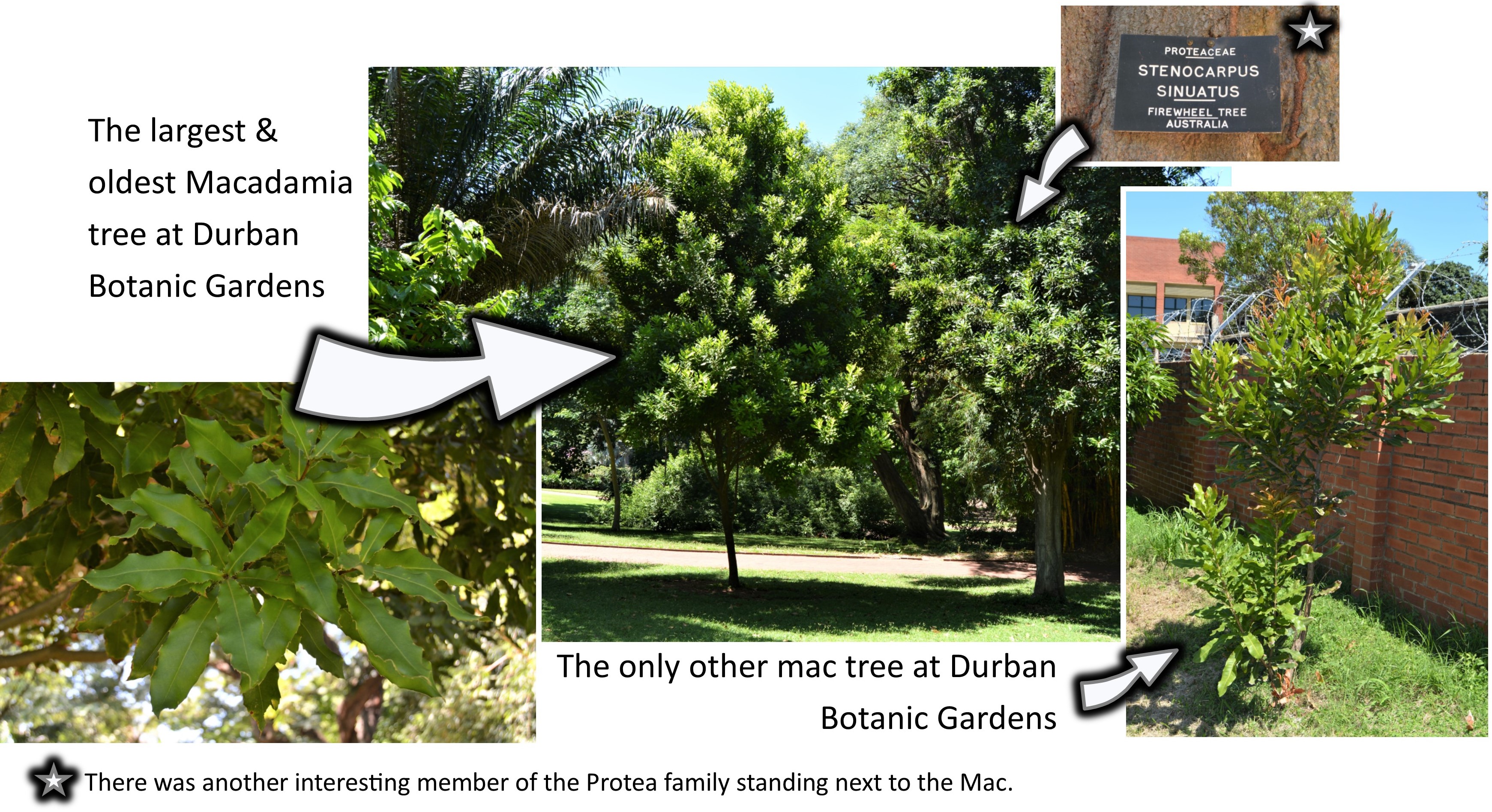

So, is this the oldest mac tree in the country? Stephen says “No, the oldest ones are at Durban Botanic Gardens (DBG) – they are the ones that these seeds came from.” So, a couple weeks after I returned home from this trip, I had an unsuccessful trip to Home Affairs and decided to pop past Durban Botanic Gardens on the way home. The first 7 people I found said that there were no macadamia trees in the gardens at all and then I found the horticulturist. She found a digital list of all the plants in the garden and listed there were 2 x macadamias. Such excitement! They have a grid-map system to locate the trees and so I headed off on a treasure hunt to find the stipulated block. No mac tree there … but that looks like one over in K4 … yes, this is the one. But it is nowhere near 60+ years old! This youngster was no older than 10 years old. So, I headed back to the horticulturist who had, at first, said that I couldn’t see the other one because it was in the nursery area. I explained the gravitas of the situation i.e.: the oldest mac trees in Africa are missing! So, she stepped aside. Again we found a mac tree but this one was no more than 3 years old. ☹

This was getting serious. No one knew anything about any other mac trees in the gardens and insisted that the latest “collection” had been completed just last year and was accurate. There are no other mac trees here! I obviously looked suitably horrified because they have promised to follow up with everyone and make absolutely sure … but I think we can safely say that those trees are no longer there. I have since confirmed with Dr Mark Penter that the grand dames at DBG have indeed departed (they are recorded to have been there since 1883 so it is little wonder).

So, where is the oldest tree?

As so many dates were not recorded, it seems that this mystery won’t be solved but here are the contenders:

- Pietermaritzburg Botanic Gardens – no planting date known

- Stellenbosch University Botanic Garden – no planting date known

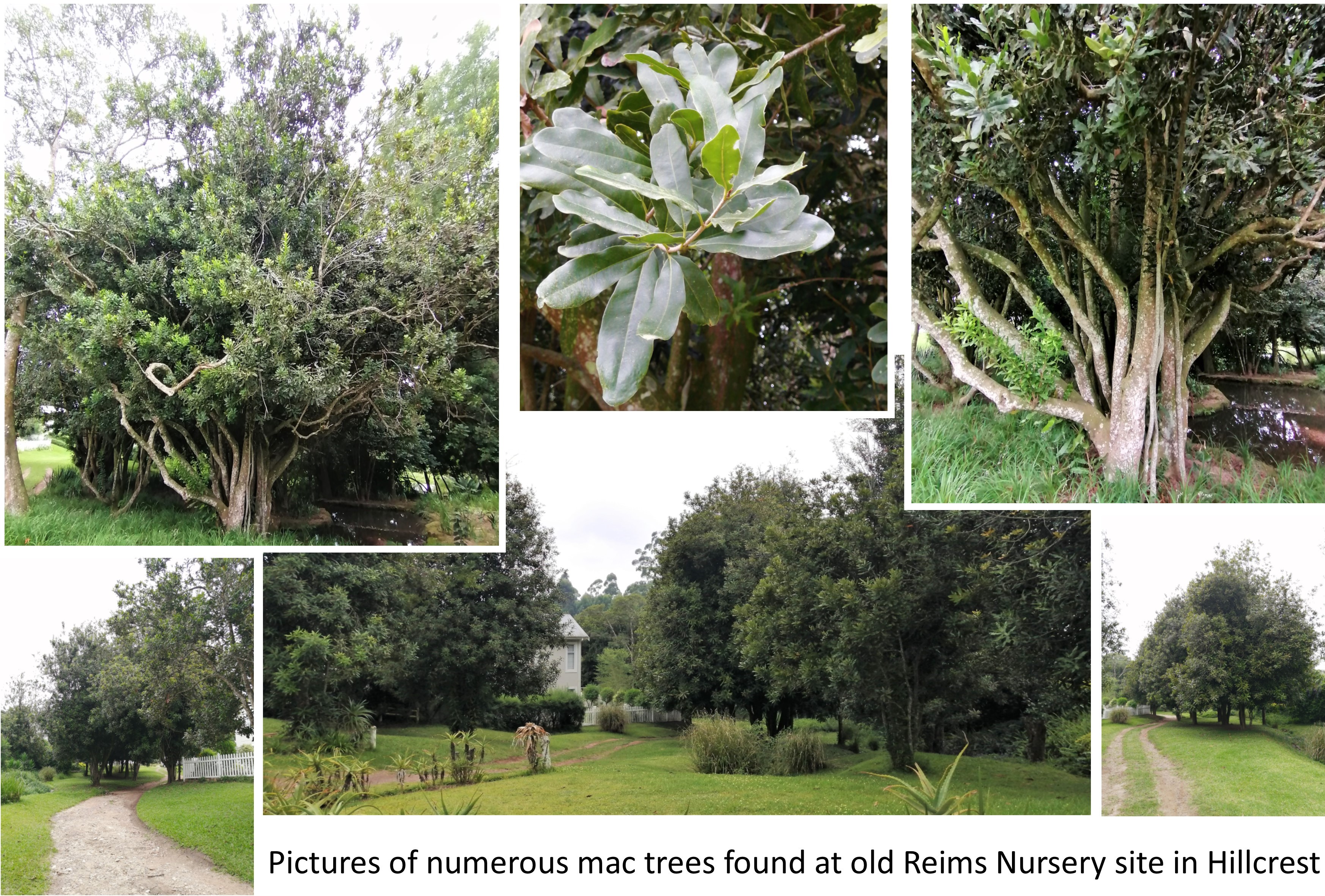

- Old Reim Nursery in Hillcrest – this nursery started in 1935 and was operational for many years but there is no record of how old the trees, still there now, are

- ARC Nelspruit – there is a variety block planted here that has trees of many species, including several macadamias. This block was initially planted in 1947 and then added to over the years. (Late) Peter Alan wrote an article in which he described visiting these trees in 1950, so they were planted at some stage between 1947 and 1950. From the orchard plans it appears they were planted in 1947 or 1948. Three trees are of the Nelmak 1 variety ( tetraphylla appearance but actually hybrids) and three are integrifolias.

Getting to know the locals

I was very privileged to engage with many wonderful professionals on this trip but the stand out for me was Dr Elsje Joubert. Without knowing me at all, and being an incredibly busy consultant AND mother of two very young boys, she happily set up all of my meetings in Limpopo. She even accompanied me to most – probably to check that she didn’t need to apologise to any of her valuable contacts 😊

She suggested I stay at Die Plaas Gastehuis in Piesanghoek, with Oom Jan and Tannie Rita. What a joy that turned out to be. Not only is Tannie Rita an absolutely amazing cook, they were both exceptional hosts and Die Plaas is one of the first planted to macs in the area.

These trees, now heavily pruned back for better stink bug control, were planted by Jan’s father in 1964 & 1965

These trees, now heavily pruned back for better stink bug control, were planted by Jan’s father in 1964 & 1965

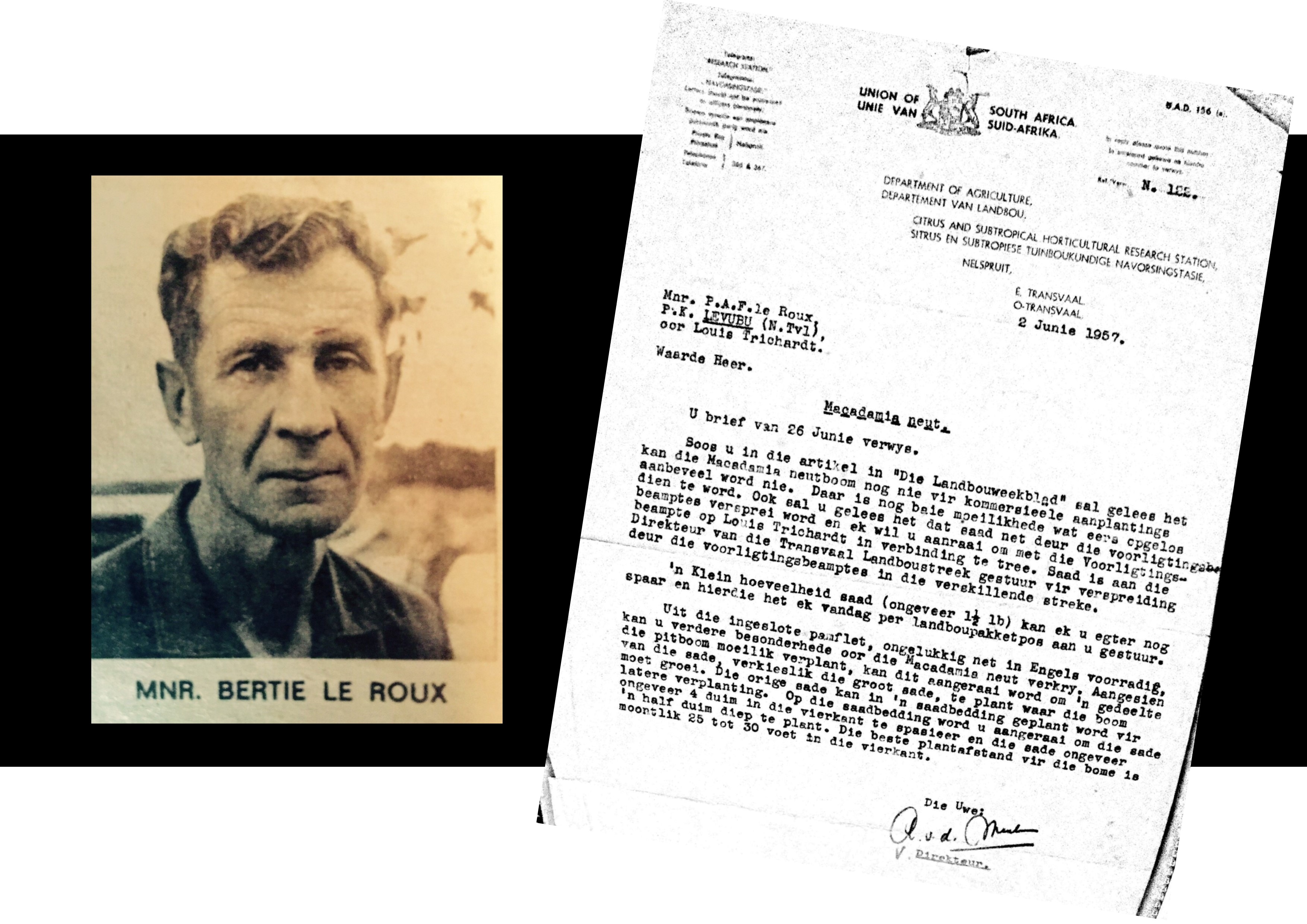

One of the other many priceless encounters Elsje set up was with the family of the famed Bertie le Roux – one of our industry pioneers. Stephen and Francois Hoffmann (Bertie’s son-in-law and grandson) made time to share their knowledge of the history of Levubu and on Arbor Farm:

Bertie’s father (Pieter le Roux) came into the area when he exchanged his cattle farm (north of the mountain) for a plot in Levubu. It was 1933 and the country was struggling with both a drought and foot + mouth disease; making cattle farming unsustainable.

Levubu was formally established in 1939/40 when irrigation plots were allocated. They were awarded on the ‘probationary system’ whereby would-be farmers proved themselves as competent and built up the capital to purchase the farms they had been working from the government who supplied most of the inputs required to farm. At the end of the season, the farmer was obliged to take his crop to the department and they sold it on his behalf. The lack of infrastructure made marketing any other way nearby impossible. Proceeds were split 3 ways: 1 – living allowance for the farmer, 2 – debt repayment for all the seeds, fertiliser, tools etc. that you took from the government store and 3 – savings account. After 3 years, if you had been successful, there would be a healthy amount in the savings account and you could use this as a deposit to buy the land you were farming.

Bertie was working in the government agricultural stores from 1953 – he then moved onto his Dad’s farm. He was used to living a difficult life in the Zoutpansberg and knew that farming success lay in growing something that could thrive in this environment.

He looked around and, seeing all the trees, wondered why so many still insisted on growing grasses.

These crops (wheat, rice, maize, peanuts) struggled. Only bananas did well without effort. A few German farmers tried litchis and they grew well. This exploration expanded to lemons and limes but the citrus roots struggled in wet weather.

Bertie knew he wanted to farm with trees but which ones? ARC in Nelspruit obtained some macadamia seeds from Botanical Gardens in Durban and distributed them amongst the farmers in Soekmekaar, Piesanghoek and here on Arbor farm. Bertie’s seeds grew well so he wrote to the government to ask for more. The response, in 1957/8, was positive for 1,5 pounds but came with the warning that this crop has not proven itself and is not commercially viable yet. They passed all responsibility to him.

Despite the scepticism expressed by the officials, he continued, eventually developing his own cultivar. It was never officially registered or named after him but Nelmak 26 was born from Bertie’s selections and has always been known as ‘Bertie le Roux’, here in the Lowveld.

Now there are better cultivars, without Nelmak 26’s characteristic to bear alternately, but it still does well in that it has one flowering and one drop, with nice size nuts.

Bertie’s first commercial orchard was planted in 1969

It has since been removed because it was always more of a trial orchard – a mixture of whatever was available at that time (all seedlings). Based on what he saw there, he made his choices of what to plant out. The oldest orchard here now was planted in 1970.

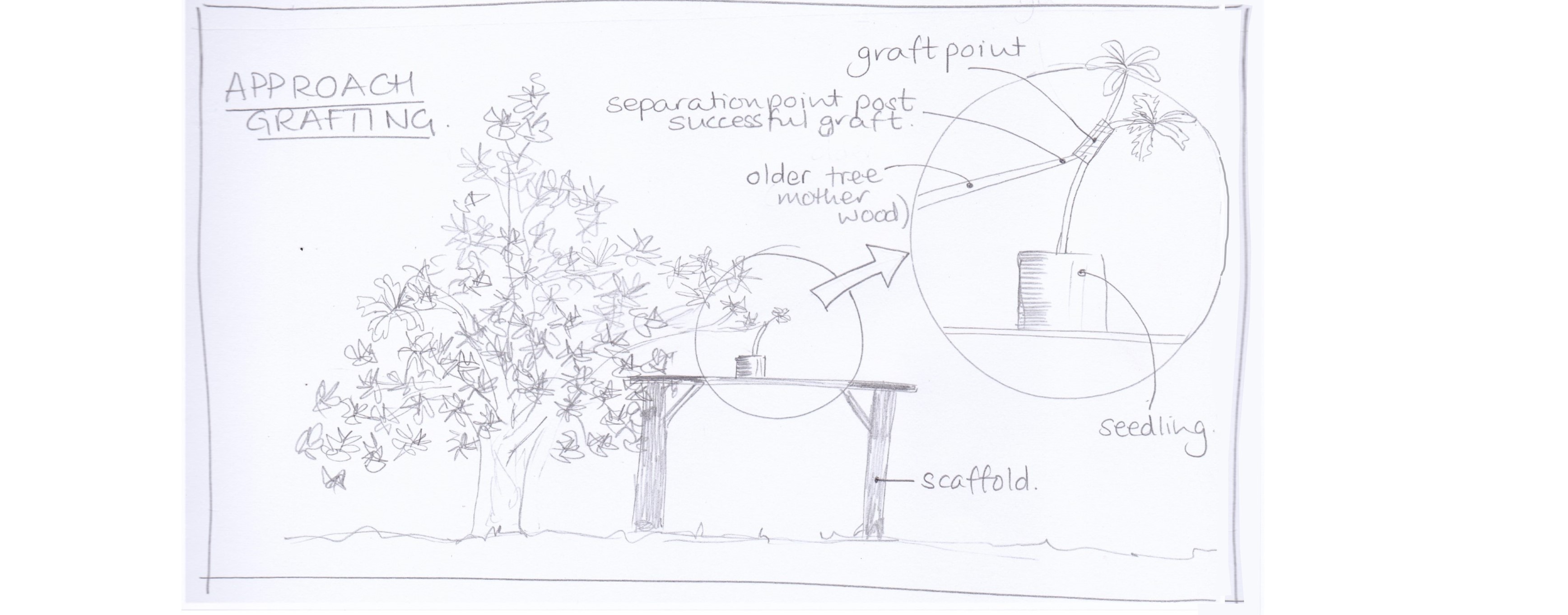

Together with Louis Botha, Bertie was a pioneer in selections and grafting. Up until now, the grafting method used was “approach grafting” which was very cumbersome. It involved a raised table or scaffold structure to get the seedling within range of the motherwood which remained attached to the mother tree until the graft had taken.

Bertie started a nursery that took the motherwood to the seedling, grafting the way we do now. This enabled them to import budwood from Hawaii and introduce new cultivars to SA.

He also worked on the other end of the process, and formed a relationship with SAD to market the produce, which was done in 1978; Canada and the USA were the initial customers.

When first payments came in, in 1978, everyone wanted to farm macadamias.

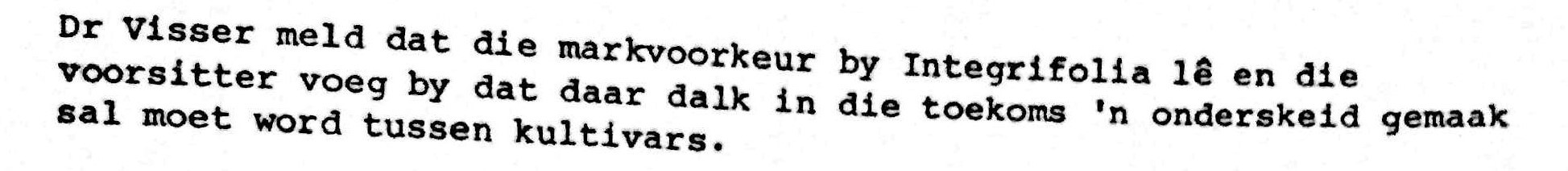

Then the question was asked; what to plant – the Hybrids or the Integs. Main difference between integs and hybrids, to the consumer, is oil content. Initially, the kernel’s energy is composed of sugars, as it matures, those sugars turn to oils. Integs take that to about 78% while hybrids are limited to about 72%. This means that hybrid nuts tend to be harder, sweeter and have a slightly darker colour, when roasted. The integs are creamer, softer and lighter in colour. Different markets have different preferences and, while this may seem like an advantage in that there should always be a market for whatever you are producing, Bertie promoted standardisation within the industry by delivering a more uniform nut. This has clearly been an unresolved dilemma as illustrated in this comment from meeting held on 7 May 1984:

Translated for our international readers: Dr Visser reports that the Integrifolias are being favoured by the market now is because, in the future, a distinction might have to be made between cultivars [So they wanted to expand their offering]

Translated for our international readers: Dr Visser reports that the Integrifolias are being favoured by the market now is because, in the future, a distinction might have to be made between cultivars [So they wanted to expand their offering]

Something that sank home for me on this visit was the real reason for grafting. It came while I was trying to get Mr Hoffmann to tell me what variety these very old trees were. He kept saying “They are seedlings” and in my ignorance I persisted to ask “Yes, but what variety?” If there is anyone (I really hope there is at least one!) person out there as ignorant as me, here is how Mr Hoffmann eventually got me to understand: “If I meet your mother and I like her, I will not be happy if I take you home as you are not 100% her.” In other words – when we discover a tree that ticks all the boxes for us, growing out her seeds will not mean we have an orchard of her; we have to clone her by either making rooted cuttings or grafting her wood onto root stock. i.e.: so, grafting is the result of wanting to clone successful mother trees. Seedlings, although they are from that mother, will never be able to do that because the seeds were most likely fertilised by another tree. And like siblings, are often very different in many ways. So, the original trees were all grown from seed, making them all seedlings.

Beaumont seedlings, although they are from a Beaumont tree cannot be classified as Beaumont

They are seedlings (a generic term to cover anything that is not a “clone” (rooted cutting or grafted tree).

A variety is a plant that was planted as a seedling. It was evaluated* and judged to be good and was then given a number or an official name. When you cultivate it, it is called a cultivar (cultivated variety).

*This evaluation lasts for a period of 15 to 20 years and can only be done by an accredited institution. Most of our cultivars today have come from Hawaii and some from Australia (e.g.: A4 and A16). South Africa has never had an official cultivar. Nelmak 1, 2 and 26 have been unofficially released / named because it performed well but they were never officially registered by an accredited institution. Latest Hawaiian cultivars have numbers but have never been officially released by the Hawaiian authorities. The Mac industry in Hawaii is being overtaken by residential / hotel expansion and they are no longer naming new cultivars. They stopped at 900 and are not even planting new seedlings anymore. Now the Australians are taking the industry forward but it is mainly a private initiative funded by the Bell family – they have an operation in Queensland called Hidden Valley Plantations. They are charging breeding rights. Unless South Africa starts to take the lead, we will be stuck with current selections for a while. Most macs have been selected for their suitability to grow well on the coast. Here in Levubu, at 600m altitude with no ocean to regulate the extremes, conditions are very different. It is thought that crack outs here are far lower because of the difference between day and night temperatures in the period of kernel development. The more extreme the difference, the thicker the shells and may be why shells on the coast are thinner and crack-outs, higher.

The industry needs a cultivar that does better overall

Currently, here in Levubu, the most popular cultivar being planted currently is Beaumont. The market vacuum (created by China’s apparently insatiable appetite) means that “anything” can be successfully marketed. But, there is a view that, in the long-term, the market will stabilise and become more selective, demanding nuts of higher Grades (0,1,2), i.e. more wholes. This will exclude much of the Beaumont crop as Beaumonts tend to deliver a smaller nut and styles of Grade 3 and smaller. It would therefore be imperative that quality-producing cultivars, that produce consistently well at higher altitudes, are discovered and released.

Issues affecting new cultivar releases are:

- An apple farmer, walking through his orchards, experiences the final product – the colour, the size, taste and juiciness. A mac farmer does not have the same experience – he can see neither kernel colour, size nor can he enjoy the taste without first processing the fruit.

- If he does happen to find a tree that he notices is producing well and goes to the trouble of monitoring it further, there isn’t really a clear process to follow to assess that tree in terms of a new cultivar registration.

- The tree’s ability to consistently repeat its characteristics in propagation is also important to assess. A farmer can propagate a tree out on his own farm and monitor that trial but this is not a recognised assessment. (Side note – I also interviewed a JAFF this week, in Levubu, who thinks he may have found an amazing new cultivar on his farm – they have been propagating it for a many years now and it out-performs anything else they have on the farm. You’ll have to keep reading every story to pick up the details 😊)

So who, when and how will we get new local cultivars? “Only when the market is in a state of balance – demand in line with supply. When suppliers are working hard to promote their produce; then quality will become a differentiating factor – essential to the successful marketing of product. When this market shift (demand for better quality) is felt in the pocket, then the process of searching for a better cultivar will really begin. I don’t think this will happen in the next 10 years,” says Mr Hoffmann. But, if you hear what the warning is, you will take it into consideration when planning your next orchard …

So what does he feel is the best cultivar available now?

“863. Very similar to 816 in terms of being a sensitive tree but it does better in this area than the 816 does. 816 just turns yellow in this heat.” He is not surprised to hear that 816 does well in KZN, where conditions are far kinder. Elsje cautions that both these varieties are prone to nut borer but reveals a few more positives for 863 in that it does not have a “sticking problem” or a husk rot challenge like 816 does up here, in Limpopo.

When we consider other produce markets like apples (Granny Smith, Fuji, Golden Delicious), oranges (Valencia, Navel, Blood Orange) and avos (Hass, Fuerte, Pinkerton) we can see the potential of this marketing-by-cultivar strategy.

I felt like I was sitting at the feet of the industry’s grandfathers …

… and this was a moment not to be squandered. These farmers have paid high school fees and it is an opportunity to pay attention and help save the rest of the industry a few expensive lessons. The prime concerns throughout the trip were mostly pest-related. This region is suffering under the persecution of seemingly uncontrollable pest populations.

- Scout: Spraying without scouting is like shooting a gun at a closed door.

- You don’t know who is on the other side, if anyone is on the other side, and whether they are friend or foe. You may spray ineffective chemicals or kill off beneficial insects unnecessarily.

- Timing: Attacking when no one is there is wasteful and harmful to the environment. Attacking at the wrong time of the insects life-cycle is similarly expensive and harmful. Without scouting, your timing is going to be off.

- Maintaining a constant barrage on the door may look like it is working because you are simply killing everything on the other side. Is that sustainable as a long-term strategy?

- Be careful: Chemicals (and their side-effects) are expensive. Tailoring your sprays to what you find in your orchards will cut back on waste and a potential build up of resistance. Select chemicals after thorough investigation of the active ingredients. Spray a range of different chemicals so that resistance is avoided. Ensure application rates are followed accurately. Ensure that application itself is done accurately with carefully calibrated equipment. Always use the gentlest, but most effective, product available. As an analogy – using a cannon on a mouse will not only destroy the environment around the mouse, it will also kill the cat who was just about to catch the mouse for you. First prize is to allow nature to take care of population explosions but our monocultural agricultural practices often throw this off balance and we then, to save our crops, have to intervene further. The more we over-react (use cannons), the longer we will pay the price of unbalancing nature (destroying the environment).

- Prune: There are many other benefits to pruning but this aspect of tree maintenance has been neglected by many farmers in Limpopo. One of the outcomes is that harmful insects have multiplied furiously in safe fortresses created by the impenetrable high, dense vegetation.

This is our chance to listen to the elders; they are passionate about those new to the industry not repeating their mistakes.

On the journey I also crossed paths with many of the processors and it was wonderful to hear all the different perspectives on the industry currently. As mentioned, the degree of differing and the extent of emotion made a story covering the processing part of our industry, exclusively, too challenging for me – I tend to put both feet in my mouth at the best of times – but I can bring you some “pearls of wisdom” that I picked up from some of the interesting people I met …

Strongest of the Strong. On the road, I pondered the fact that farming, as a profession, is prone to such passion. Discussing this with one of the farmers, we agreed that it is probably because it is not just an occupation – it is a heritage, a lifestyle, a home, a business, a retirement. It demands ALL of you. And farmers happily give all they have to be farmers but then … expect passion! And when the land is tough, like in Limpopo, expect radical passion. Another point to consider is that The Great Trek started in the Cape and it ended in this area so if you expect to meet anything besides hard-core people here, you are wrong. It was also an endemic malaria area – survival was reserved for the strong alone.

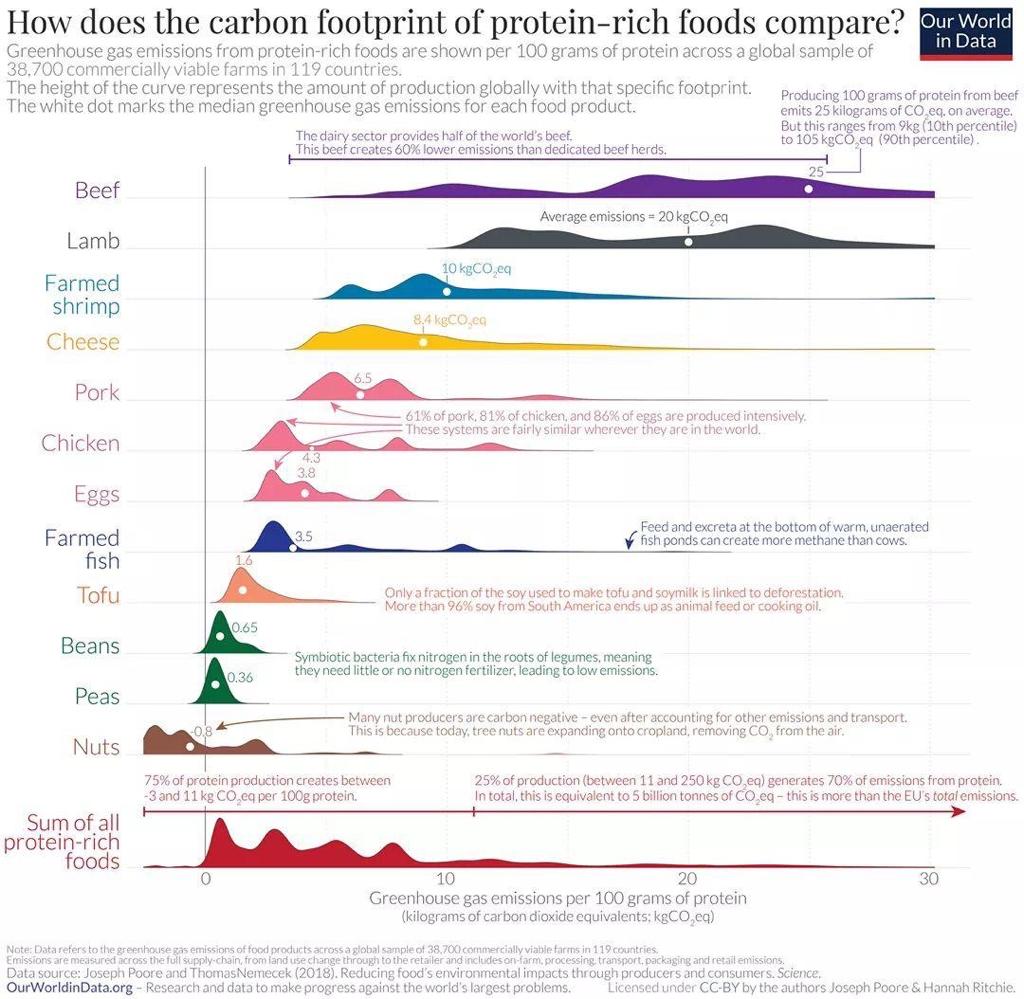

Environmental Nod. When it comes to protein-rich foods, ‘nuts’ is the only one that has a carbon-positive footprint. This is extremely important as we struggle to save the planet we seem to destroy so easily. Some of the characteristics that make this possible are the facts that it is a tree-crop and it is a small object (so freight costs are low).

Elsje added that when they (as scientists) look at satellite Natural Digital Vegetation Images, it is clear that nut orchards are far less stressed than most other crops, even other tree crops like bananas and avos.

The incredible nutritional value of nuts is also something to contemplate – they are the embryos of plant life – jam-packed with nourishment, something we don’t often get to eat (think about apples, citrus, peaches, avos, litchis, cherries …). That will mean the popularity of this super-food will be a long-term phenomenon.

International marketing. In the early days, Levubu was the epicentre of the SA mac industry. The farmers sold all their produce to the local co-op who cracked the nuts at a small facility they had established in Venda. Marketing was done by SAD (SA Dried Fruit). A poor decision by them led to an epic financial disaster in the industry and a lot of drama unfolded. Of course, boers always “maak ‘n plan” and in 1990 the first privately-owned mac processing plant was opened in White River and it offered processing as well as marketing services to its customers. This saw the industry reorganise itself and today we have between 25 and 30 processing facilities available to the farmers throughout the country. The rapid industry growth has resulted in a rather fractured processing and marketing landscape with little cooperation and alignment. There is no doubt that, as market forces stabilise, it will settle, and there will be greater unity.

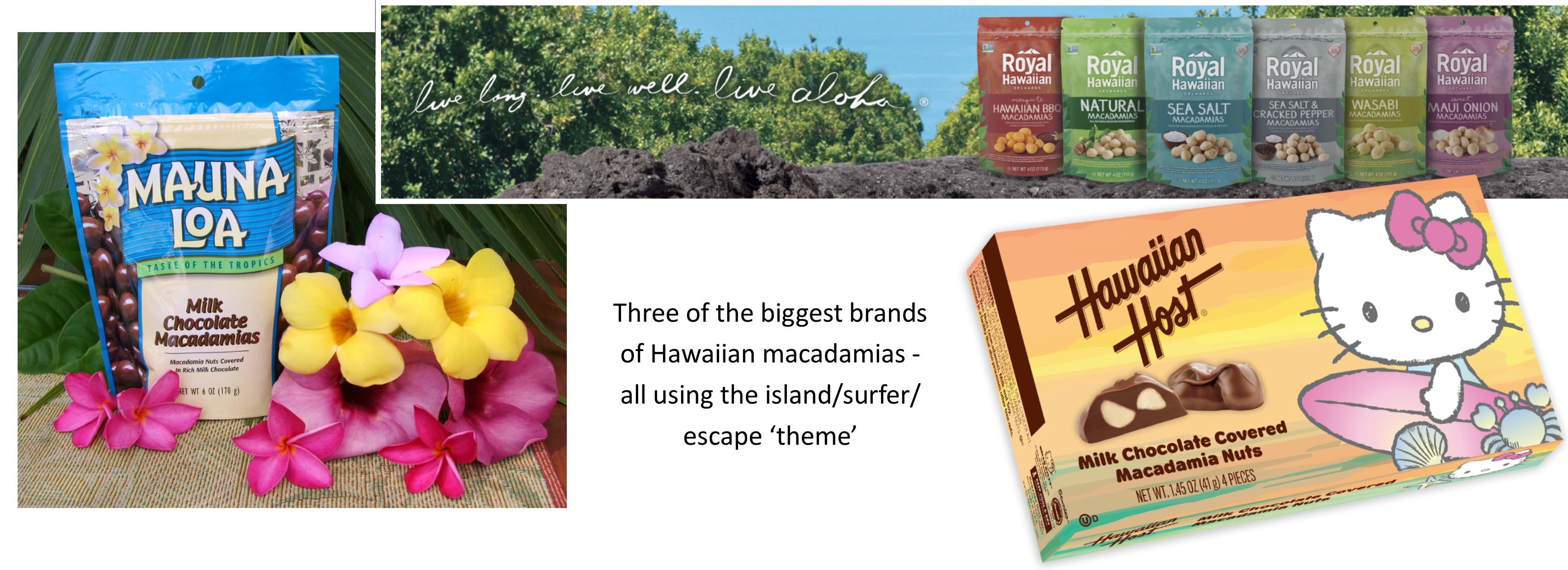

Although SA is currently the world’s largest producer of macs, we consume almost nothing. Besides the nut-in-shell market (China), the world’s largest consumer of macs is the USA. With Hawaii being one of their states (although it is almost 4000kms away) and the successful marketing strategy of associating macs and island holidays, the US effectively consumes almost all its own produce. And then the majority of the rest of the world’s produce as well.

The Germans are also big mac-lovers. And, although Holland appears (on paper) as one of the world’s largest consumers, this country is actually a gateway to the rest of Europe.

It goes beyond farming

I think back to the days I was exclusively involved in the sugar industry. Farmers would long for more choice when it came to processing and marketing their product. Being dictated on process and price was suffocating and frustrating. So, those of you who are now farming macs, I hope you are enjoying the choices you have. But I imagine deciding which option to go with is a stress in itself. As a farmer, your day is full just trying to find the best cultivar, manage foliar spraying vs granular feeds, taming wildly growing trees, fending off swarms of stink bugs, negotiating with labour (and and and) …

When it all seems too much, it can be helpful to go back to basics:

- Consider what works FOR YOU. Every farming operation is unique and therefore has a unique solution. Listening to neighbours and friends should form part of your research but the ultimate decision should be one that fits YOUR needs.

- Question and investigate everything. e.g.: are the Chinese really eating all the nut-in-shell they import? Or are they processing them and sending them out to compete in the kernel market at lower prices? Customer-turned-competitor? … a scenario to be considered.

- Consider marketing strategy when choosing a Handler.

- Spread the risk. Make sure that your nuts are marketed into a variety of markets. While supplying the Chinese early in the season works to generate early season cash-flow, it should not dominate your portfolio, least that market is threatened in some way.

- Long-term vs short-term strategies. When the primary goal is to realise the best price on offer it usually indicates a shorter-term strategy. Strategies that emphasise stability will be linked to longer-term approaches, e.g.: some handlers are actively developing demand in the ingredients market. This will cater for the large Beaumont supply forecast (which will be heavy with ‘pieces’ rather than styles 0,1 or 2). It takes a long time to convince a manufacturer to 1). develop a product that uses a new ingredient and 2). develop the faith required to rely on your consistent supply of that ingredient.

- Collaboration. A strategy that collaborates with other agencies to open up more markets is to your advantage, e.g.: pooling product with other mac producers to create more reliable supply to customers will develop and open up more distribution avenues.

Yoh! This virus is quite a challenge to understand … I was of the opinion that we have all been over-reacting (especially when I see the Australians buying out all their toilet paper supplies) but, listening to our President effectively locking the country down last night (Sun 15 March) I have to consider that I may be missing something. I consulted a few people wiser than I and here are some points to ponder:

- The situation changes hourly and will continue to do so. By the time you read this, it will probably be obsolete.

- As China is no longer the epicentre of this pandemic, our reliance on this market is possibly not going to bite us as hard as we initially anticipated.

- The honest truth is that no one really knows what the effect of Covid-19 pandemic will be on the Macadamia market. This event is so unprecedented that there are no guidelines on what to expect.

- Early indications are that demand is still good and buyers are eager to contract. Some are of the opinion that this event might actually increase demand for macadamias due to people spending their money online (where most of our sales are) and on luxury snacks, rather than travel and eating out. We also fall into the “healthy snack” category, which might favour us since people are trying to build up their immune system before the pandemic hits them. Our product is also well suited for the online market (high value and light) – it is expected that online orders will increase as people are locked in, while it is possible to stock up on mac supply if you are worried that you might be in a lock-down position.

- We do, however, expect a disruption in the supply chain. This should not be a major problem for kernel buyers in the US and Europe who normally plan ahead, but it might create panic for those suppliers who are over-dependent on the Chinese NIS market only. I think this is the year where you need to have an agile NIS strategy for China – have supply ready while there is an opportunity, but be in a position where you can walk away if you have to, on short notice (this is easier said than done… ).

- It is still early days in our processing season and the pandemic. I think the situation might be very different in a month or two from now.

- Beware the Panic: Traders smell blood and will take advantage of any situation by waiting until prices hit rock bottom. End consumers will still pay the same price.

- A young, fragmented industry is more susceptible to abuse by Traders than one that is unified and coordinated. Usually only large suppliers can satisfy end user demands, smaller suppliers mostly use traders.

And what about Salmonella?

I know, I know … raising yet another “bug” in the light of Corona may not be fair but it is a topic of concern in the industry and worth bringing attention to …

Salmonella infection (salmonellosis) is a common bacterial disease that affects the intestinal tract. Salmonella bacteria typically live in animal and human intestines and are shed through faeces. Humans become infected most frequently through contaminated water or food. CDC estimates Salmonella bacteria cause about 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths in the US every year. Food is the source for most of these illnesses. Salmonella is a bacteria that commonly causes foodborne illness, sometimes called “food poisoning”.

The US is the primary destination for our kernels. They have recently advanced their testing capacities with regards to Salmonella and have already turned away sizeable shipments for treatment. This treatment is not only cripplingly expensive but the fact that we supplied infected nuts does not benefit our reputation.

So, what can be done about it?

Because ours is one of the few ‘fruit’ that is always harvested from the orchard floor, we face elevated risk and have to follow much more stringent standards of hygiene than usual.

Here are some areas to focus on:

- Clean orchard floors. This is a quite a broad sweeping statement, open to interpretation. Some processors would prefer that no animal waste (e.g. kraal manure) is used in the orchards at all. Farmers are then faced with a choice between providing trees with the proven nutritional benefits of cattle and chicken waste or reducing salmonella risk.

- Pick harvest up quickly. This is an easier one to work with and often just requires careful management of resources.

- Keep your nuts dry. Damp conditions elevate the risks of rot AND salmonella.

- Keep your nuts clean. Rodent, animal and bird controls around the nuts are vital. Cats sleeping on crates in sheds, dogs urinating on nuts as they walk past, rat pandemics (NB: rats constantly urinate wherever they go. That is how they retrace their path at night) are all factors that need to be eliminated. I was rather horrified to hear how some suppliers deliver nuts to the processors … there was even a case of loose nuts arriving on a vehicle that had just been used to move livestock – clear from the faeces and urine all over!! Birds in warehouses also increase the risk of salmonella. Nuts should be covered when in storage.

- Keep your nuts cool. A simple one … e.g.: when nuts are waiting in the orchard to be collected, leave them in the shade of the tree rather than the sun.

- Use suitable storage materials. Nuts stored in plastic bags are prone to sweat, creating the ideal environment for bacteria growth.

- Basic factory hygiene. Make sure your staff have washed their hands (should be simple after what Corona has taught us) particularly in the sorting lines.

Processors are the ones who carry the responsibility of how our nuts leave their sites. Therefore, how they arrive to their facilities is a huge factor. If farmers continue to endanger the quality standards, processors may be forced to turn their produce away. That would be an awkward, but necessary, situation because Salmonella infections can earn us, as African suppliers, a poor reputation on the International market – something we cannot afford!

Just writing this overview fills me with such a sense of privilege.

To be a part of such a progressive, growing and thriving industry is an honour. I look forward to serving you all for many years to come. The next article is on Water Management (I keep calling it Irrigation, but it is so much more than that) and will be published mid-April.

For those who see the value of advertising alongside this edition, drop me a mail at debbie@tropicalbytes.co.za (or check the options on https://www.tropicalbytes.co.za/advertise/ )

Thanks for assistance in compiling this article goes to:

Dr Elsje Joubert – Agricultural Consultant, Levubu

Mark Penter – ARC, Nelspruit

Stephen and Francois Hoffmann – Arbor Farm

Joubert Family (Die Plaas)

Golden Macadamias, Green Farms, Ivory Macs, MacRidge, Mayo Macs, Royal Macadamias, Tzamac. (in alphabetical order)

And the other “Anonymouses” – you know who you are.