| Date | 12 June 2019 |

| Area | About 20kms west of Nelspruit |

| Hectares under mac | 55 hec macs in production: 20h over 10 years. 35 h now 5 years old.

Another 60 h young trees: 40 h: 2 year olds. 20 h: 1 year old |

| Soils | Deep reds |

| Rainfall | Usually about 810mm annually |

| Altitude | 840m; a little higher than Nelspruit itself |

| Temperature range | About 4’ cooler than Nelspruit itself – reason why Kiwis may do well here. |

| Varieties | Beaumont, Nelmak 2, 816, A4. |

| Other crops | 10 h Lemons (soon to be 20h), 40 h Guavas, soon to be avos as well. |

And so we meet yet another amazing farmer who has not been born into the profession. Farming is not an easy vocation to get into, unless you inherit it, so when I find someone who has enough passion to break into this ‘high-barrier’ career, it’s always worth listening to their journey, particularly when they are successful. And Jaff is VERY successful! For the last 6 years he has been one of Mayo’s top 3 farmers.

Jaff bought this farm in 2006; it was producing veggies and tobacco at the time so he continued with this until the local canned food factory, his largest customer, closed down. The tobacco didn’t fare as well as it had previously so he was looking around for something new when he came across 20 hectares of 9-year-old Beaumont trees that were going begging on a neighbouring farm. Jaff decided to transplant them on to his farm. Now I always thought that mac trees couldn’t be transplanted …

TRANSPLANTING

Not so! For this first transplanting, Jaff hired a tractor-mounted tree spade and built a custom trailer that would take 6 trees, preserving their ‘cone’ shape and therefore most of the soil around the roots. He wet the soil around the tree thoroughly, pruned it back to about 2,5m (no leaves), and then the spade ‘dug’ and lifted the trees into the trailer. He wet them again and then moved them to his farm where a TLB lifted them up and placed them in the pre-dug hole that had a lot of water and root-stimulant in it. He did not add any fertiliser or compost. This happened in Nov Dec and the trees were transplanted within 2 days of being dug up, depending on the heat of the day. He cannot remember the exact figures but knows it was no more than a 10% loss of transplanted trees.

This transplanted orchard was laid out in an 8m x 5m spacing configuration and then Jaff put a row of small trees down each row, making it a 4m x 5m spacing. Eight years later he transplanted the younger trees out to establish a new orchard. This time he didn’t invest heavily in the process (hiring a tree spade is rather costly) and executed the transplant with a single TLB. He pruned the trees back to about 20% of the leaves, dug on either side of the tree, strapped the tree trunk to the TLB and then scooped the tree, and as much soil as possible, out, placed it on a trailer and moved it to the new block where holes had already been prepped. Again, no fancy fertilisers or compost, just water and root-stimulant. This move was done last September, when rainfall was half what it should have been and Jaff admits that he didn’t focus on the move – he left it all up to staff. As a result, two integral facets of the move were sub-standard: 1. some trees were left open for 4 to 5 days, instead of being moved and planted quickly. 2. post-transplant watering was not what it should have been, given the low rainfall. Subsequently, he thinks he lost about 15% of the trees moved.

So, it seems that mac trees (well, Beaumonts anyway) can be transplanted fairly easily. Jaff did point out that all his transplanting exercises have been between neighbouring farms, or on his own farm. If the trees had to travel any kind of distance, he recommends ensuring that the roots are kept wet and covered at all times, right up until planting.

The first orchard, transplanted from a neighbour at 9 years old.

The first orchard, transplanted from a neighbour at 9 years old.

Jaff transplants large trees when gapping rows. The trunks are painted with white PVA to protect them against sunburn when there are almost no leaves.

Jaff transplants large trees when gapping rows. The trunks are painted with white PVA to protect them against sunburn when there are almost no leaves.

Jaff believes Nelmak 2s would also transplant well. He’s not sure about 816s but he will know by the end of this year when he plans to move about 100 specimens of this cultivar. Generally, the trees take about 2 to 3 years to recover from a transplant and will bear about 2,5 tonnes / hectare in the 4th year. By year 5 (after transplant) they’ll be back to the normal production of a fully grown tree. He recently advised a fellow farmer who transplanted about 1000 trees and they only lost 5 trees! That’s 0,005%!!

EXPANSION

Jaff recently invested in a new 500-hectare property. It is a blue gum plantation so the land prep required to establish macs is extensive. He will go slowly, with 40 hectares annually, but Jaff is not planning exclusivity with macs; he also intends to extend his guava crop, as they do well in this climate. Kiwis are also an attractive option that Jaff will be exploring. His avos were ordered 3 years ago and were about to be delivered shortly after my visit. Unfortunately, theft is a challenge with all this produce, and avos are up there with macs in terms of risk.

THEFT

A neighbour recently had a break-in to his shed. The thieves got away with 1 tonne from the bins. The farmer put a wildcam up and two nights later, they came back. In the time that it took the farmer to rustle up support and get to the shed, 2 tonnes were already in bags. 4 to 5 men were involved but only 2 were captured. Farm patrols and supplementary security is impacting the crime – Jaff is not too concerned.

NURSERY

Jaff produces his own trees and uses these to establish all new orchards. A couple of farmers we’ve interviewed have warned against this practice so I was interested to hear why Jaff thought it was a good idea. The answer was simple – it saves him between R800th and R1mill (per 100 hectares of new orchard) and he prefers to use this money on land prep and irrigation. He also believes the trees are more successful because they are completely acclimatised to the exact area. To a large extent, this can be also be achieved if you buy in from elsewhere, you just have to leave them in their bags, on your farm, for a few weeks before planting out.

Left: 3-month-old root stock. After trialling numerous substrates, and combinations thereof, Jaff has established that river sand is the best. Right: Beaumont trees ready to be grafted.

Left: 3-month-old root stock. After trialling numerous substrates, and combinations thereof, Jaff has established that river sand is the best. Right: Beaumont trees ready to be grafted.

So far, Jaff has successfully produced Beaumonts and Nelmak 2s in his nursery. He is about to begin a batch of A4s – he believes they may be more difficult so will be taking the process cautiously.

Jaff always identifies high bearing trees as woodstock donors and ring-barks the small branches in preparation for the ‘operation’. He is currently conducting a long-term trial to establish whether it is best to use young trees or older trees for woodstock.

CARING FOR YOUNG TREES

As there is very little frost on this farm, Jaff doesn’t need to cover or protect trees against the elements.

When raising the topic of staking, Jaff says that it is a matter of strategy; if you choose to ‘chase’ your trees (promote early, rapid growth), then they will require staking until they are strong enough to withstand high winds. If you choose to walk a more measured approach in the early years, trees can manage independently. Personally, he chooses the ‘chasing’ option and therefore has to stake.

VARIETIES

When I asked which varieties Jaff recommends to fledgling mac growers, he explains that, for him, it depends on how much land you intend cultivating to this nut. If it is only about 40 hectares, he would choose Beaumonts because of the constant, large yields. 60 hectares – he would plant 40 hectares to Beaumont and 20 hectares to Nelmak 2 which will add some nice whole kernel to the basket. On 100 hectares, Jaff would plant 40 hectares of Beaumonts, 40 hectares of Nelmak 2 and 20 hectares of 816 – this will further enhance your mix with a healthy crack out rate (816 gives around 45% crack out). It is only when you have a solid foundation of trusty ‘dependables’ that you can supplement with unstable, often alternate bearing, 816s. “One year you can get 4,5 tonnes per hectare and the next it’ll be only 3 tonnes”, winces Jaff, “add to that the fact that they are far more susceptible to climatic influences and you have an undependable tree that should only be planted to add diversity.”

“Beaumonts need less water and less food. 816s need attention. A4s are like a cross between Beaumont and Nelmak 2, which are also hardy but not as much as a Beaumont. Nelmak 2s are nice, quick growers although they come into production about a year later than the Beaumont. In year 3, when a young Beaumont orchard delivers approx. 500kg/ha, Nelmak 2 will deliver about 80kgs/ha. From year 4 onwards, they’ll deliver equally.”

Cross pollenating is still a science that my pea-brain struggles with. Just when I think I have grasped the concept, it dissolves into mystery again. Jaff could not shed any light on the topic as he is similarly uncertain about the process. He explains that Nelmaks flower 4 to 6 weeks earlier than the Beaumonts so these two cultivars certainly miss out on date night. 816s could possibly get it together with the Nelmaks, as they are also early out the blocks but Jaff doesn’t worry about this too much. Just in case, he does keep bees, although not as many as most farmers. The recommended ratio is 5 to 7 hives per hectare and Jaff only uses 5 to 7 hives for 20 hectares. He suspects that mac pollination may be more to do with the wind than the bees.

LAND PREP, SOIL MANAGEMENT AND SPACING

Jaff’s laissez-faire nature radiates when he explains, “Speak to 10 guys and you’ll get 10 different answers on land prep. There is no wrong way.” He goes on to clarify that how much, and what, land prep should be carried out is primarily dependent on soil depth. Currently ridging is very ‘en vogue’ but Jaff believes it is unnecessary when soil depth is sufficient ie: at least 1,2m. As he has these nice deep soils, Jaff opts not to ridge, especially as moisture retention on a flat gradient is far better than on a slope.

Jaff begins new orchard prep by ripping the land. He used to rip the whole area but lately he has only been ripping the rows where the trees will be planted, to a depth of about 600mm. He uses a 1,2m wide 3-tooth ripper.

After trying various options, Jaff is certain that 9m x 5m is the optimal spacing pattern. Experience has taught him that “bonsai trees” all planted on top of each other cannot produce as much as a bigger tree. He grows his to a standard height of 5,5m.

Five years ago, Jaff had a 8-year old orchard, spaced at 5m x 4m. He was getting 16 tonnes from this almost 3-hectare block. The following year, yield slipped to 12 tonnes, then 9 tonnes. When it continued to decline, to only 7 tonnes, he decided to take every second row out. Now, he’s getting 5,8 tonnes/hectare from this orchard which is as much as he used to get, but with half the trees. This lesson played a large part solidifying his more-spacious-than-average layout going forward.

In an effort to loosen and oxygenate compact soils, Jaff rips, with a 2-tooth ripper, all inter-rows, every 4 to 5 years. He places one tooth under the edge of the canopy and the other about 350mm away from that. This practice doesn’t damage the roots, it just opens up the soil for new growth. He first did it about 3 years ago and he was pleased with effect.

MOISTURE MANAGEMENT

There’s no doubt that our most abused and unappreciated resource is fast becoming the greatest risk to farmers. In fact, we cannot even limit the topic to ‘Irrigation’ anymore as the science around managing this precious resource now encompasses far more than just putting down water.

On top of greater scarcity and higher demand, rain patterns also seem to have changed. Jaff explains that it the whole lowveld (Tzaneen, Lydenberg etc) used to get a far more uniform (in terms of volume and timing) rainfall, but now it is very inconsistent and sporadic. Last week, Nelspruit had about 16mm. Here, on Jaff’s farm – not a drop. Then, a week later, Jaff got 1,5mm and there wasn’t a drop that fell in Nelspruit.

Water to this farm comes via the canal system, fed by the Witklip dam. Jaff usually stops irrigating in October and only turns the pumps back on again in April / May, preferring to limit irrigation to critical stages of the mac trees’ cycle; those being flowering during May / June and nut set, in July / August. He installed chameleon probes six months ago and, since then, has discovered that he has been under-irrigating. He is understandably excited to see how his new irrigation programme will further increase his yield – remember, he is already getting an average of 5,8t/h.

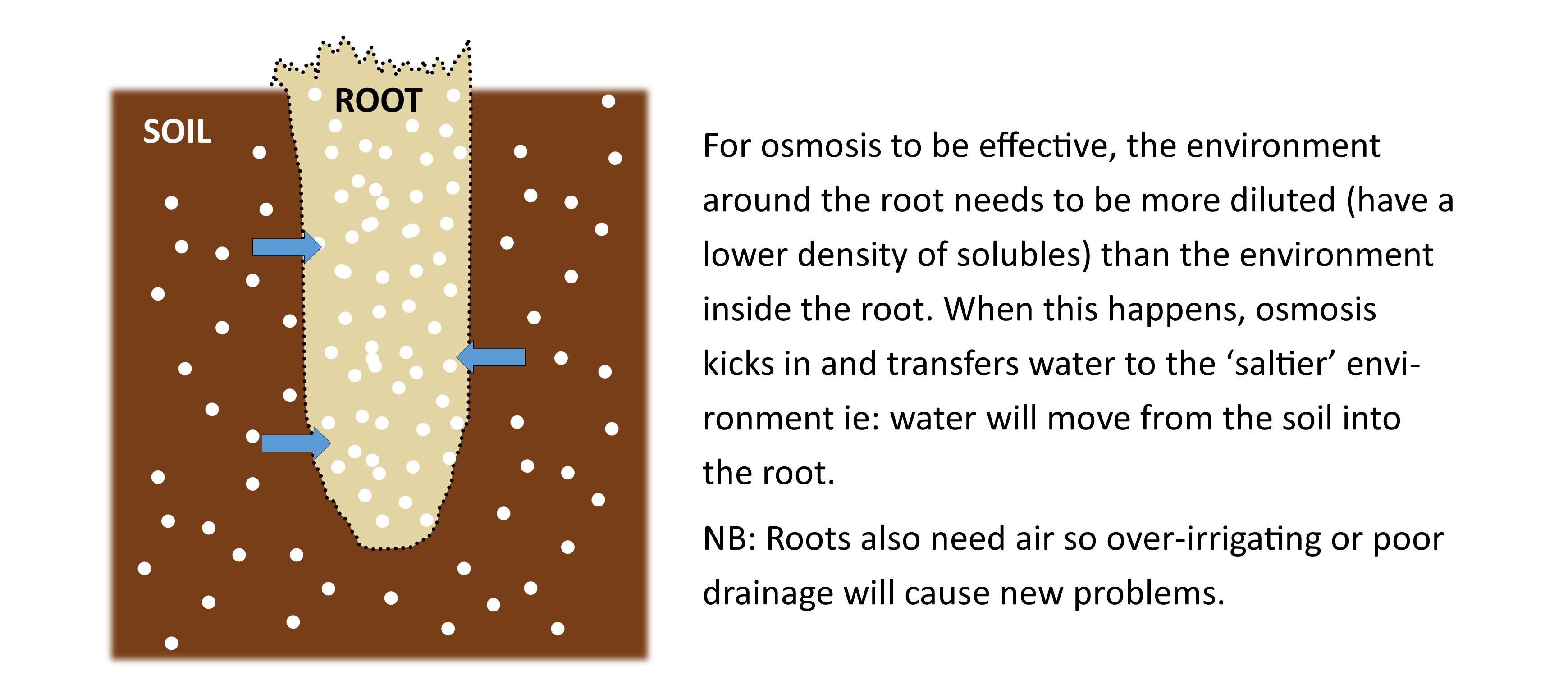

As usual, I am going to be bold enough to share something that most of you probably already know, but that I found interesting, and maybe there are a few others who can learn from it: roots take up water by osmosis. For this process to happen effectively the concentration of solubles in the soil surrounding the root need to be lower (more diluted) than the concentration of solubles in the root.

So, effective moisture management means finding a balance between keeping the soil at a lower solution concentrate (higher dilution) than what is inside the plant root but also to leave the plant with air (roots needs oxygen) so drainage is imperative. Basically, plants need sufficient, moving water to really thrive.

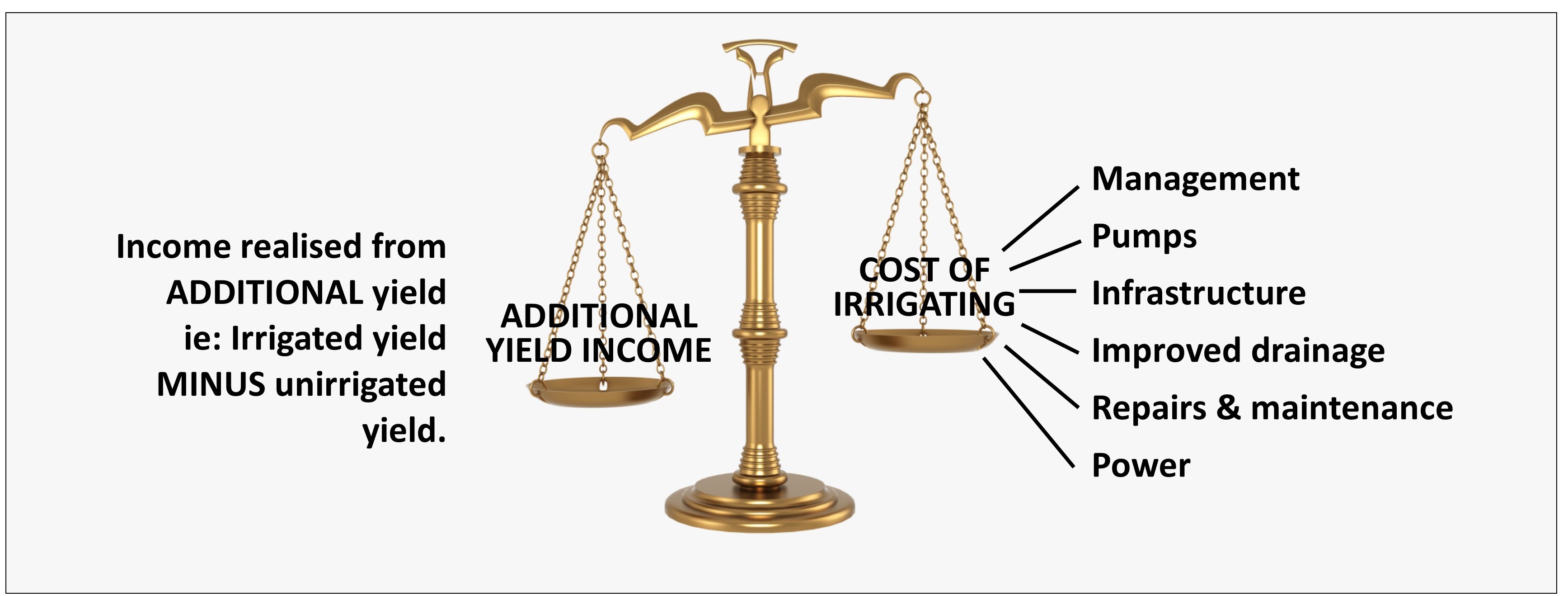

Jaff has chosen to use microjets to apply water in his orchards. The fact that they are adjustable allows him to more accurately cater to the specific needs of the trees. Microjets can also help manage micro-climates during a heat wave. Although drip irrigation doesn’t have the capacity to do this, it does have the advantage of being able to constantly feed the trees a little bit at a time, with moisture and supplements. It can also be controlled remotely. This balanced assessment of both methods made me wonder what Jaff has planned for his new farm … and his answer was intriguing: he will be dry-land farming the macs and lemons. As reported previously, the benefits of irrigation need to be assessed against the costs thereof.

Until you are sure that the income from the ADDITIONAL yield (as a result of irrigation) is higher than the cost of that irrigation, it is not a wise investment.

Until you are sure that the income from the ADDITIONAL yield (as a result of irrigation) is higher than the cost of that irrigation, it is not a wise investment.

Jaff explains that he has observed that a sick/dying tree will produce a prolific yield the season before it dies. It is nature’s way of sustaining the species; a stressed tree maximises its fruit in an effort to replace itself. So, should we not be trying to keep the trees stressed enough to produce prolifically but healthy enough to survive? It is a fine and dangerous line to walk but irrigation is possibly a step too far to the comfort side and maybe a factor in underproduction … Jaff is intrigued to find out.

FERTILISING

And here again, we can learn from this astute businessman as he considers returns on investment above ‘what everyone else is doing’. The essence of Jaff’s fertiliser programme is to get the most return from the least expense. He also constantly tests things instead of accepting what he’s told.

When Jaff first started with young trees (remember his first orchards were transplanted from the neighbour) he trialled two rows of a block by giving them 25g granular LAN within 3 months of planting, despite having been told that this would burn the roots. He gradually increased this dose until each tree was getting 100g by the time it was 1 year old. Compared to the rest of the block, these trees flourished; you could see the difference, even in winter flushes. Jaff eventually settled on a programme that starts young trees (4 months old) on 100g of granular LAN each. He currently has 4-year-old orchards that received this programme and are delivering 1,2 t/h. Again, we find ourselves considering the options …

In Jaff’s experience, the multi-part programme would cost around R15000 per hectare per year. His LAN option, only R2000/hectare. He does not believe that the more expensive programme would deliver more than R13 000/hectare, in yield, and is therefore not a wise investment.

Another thing Jaff does is add ‘Rescue’ to the soil mixed in around a young tree when planting. Rescue is a compressed black pellet that is predominantly chicken manure – Jaff adds about 800g to each tree hole. He says that Guano (bat waste) can also be used but cautiously – this stuff can burn young trees.

After this initial feed, the trees will only get LAN, every second month, until they are 2 years old. Soil and leaf analyses are then carried out and soil and foliar feeds adjusted in line with recommendations. Generally, at year 5, when most trees are in production, Jaff implements a supplemented fertiliser programme by using products like 5:1:5.

Jaff advises that foliar sprays are tricky. Soil-based fertilisers can be put down, the soil drenched and the trees will take the supplements up as required. Conversely, foliar feeds won’t be absorbed unless the little transpiration ducts on the leaves are open. Survival techniques mean that they carefully control their respiration. Humidity, wind and temperature all has to be perfect for this to happen, making the window of opportunity very small.

Foliar feeding is like force feeding and can turn into a big mess as opposed to making supplementation available in the soil and allowing the plant to take it up when it is ready.

Foliar feeding is like force feeding and can turn into a big mess as opposed to making supplementation available in the soil and allowing the plant to take it up when it is ready.

Nevertheless, Jaff does administer foliar feeds but he says this is very expensive and he’s not sure that it is worthwhile, although some micro-elements are best absorbed by the leaves (eg: copper, boron and zinc). I sense another trial coming up …

Jaff sprays copper once every 2 years. I was intrigued to learn that this element has to be sprayed alone as it reacts poorly with other elements.

Left: Manganese deficiency (but it does look like tree was negatively affected by something else and it may be showing Iron deficiency on the other leaves) Centre: Iron deficiency Right: Although this presents like Glyphosate (Roundup) damage, Jaff says that this tree has been repeatedly browsed by duiker, giving it this appearance.

Left: Manganese deficiency (but it does look like tree was negatively affected by something else and it may be showing Iron deficiency on the other leaves) Centre: Iron deficiency Right: Although this presents like Glyphosate (Roundup) damage, Jaff says that this tree has been repeatedly browsed by duiker, giving it this appearance.

Jaff advises that it is often best to replace a sick tree, rather than try to nurse it. Phytopthera is often an underlying issue in many ailing trees and is very difficult to overcome. A good indicator as to whether their time is up is to watch the nut production; as mentioned earlier, higher than expected yields are often a clear indicator that the tree will die.

Once again, we find an advocate for mulching in this Jaff, although he admits that it can get expensive. He used to get chicken manure from a local egg farm. He mixed this with husks and prunings. It took two to three years to break down but worked really well. Now that the egg farm has contracted its litter to a single consumer, he has had to buy in cattle manure – the results are still good but the cost has escalated.

Recipe: Husks + manure + chipped cuttings + time = great compost / mulch

Recipe: Husks + manure + chipped cuttings + time = great compost / mulch

PESTS

When it comes to pest management, Jaff is clearly doing a lot right, especially as his unsound kernel is consistently among the lowest in the country (in his processing group).

He uses moth traps to establish borer and FCM levels and he often has to spray. He does not follow a spray programme though and constantly checks, even the week after spraying, just to verify efficacy. He also changes chemicals regularly, keeping resistance at bay. He conducts stink bug scouts every month as well as the week after a spray.

Jaff uses a Jacto 2000 airbus (on small trees) and a 3000 Florida (works with a tower) on the larger trees.

Jaff uses a Jacto 2000 airbus (on small trees) and a 3000 Florida (works with a tower) on the larger trees.

And now for the big reveal of what I suspect might be Jaff’s secret weapon in pest management … a bejewelled army of peacocks; Jaff says they belong to his wife but they are very effective insect eaters and do a wonderful job in the orchards – so much so that they now form an integral part of his pest management plan. The 55-odd finely feathered fowls do a great job of cleaning the orchards of nymphs and larvae, quite literally nipping any infestations in the butt!

PRUNING

Jaff usually prunes himself but this year, he got contractors in because he had all his people in the processing plant to get through the harvest quickly. He insists that pruning is a simple activity – all that has to be done is to ensure that the trees are kept at a manageable height and that there are sufficient windows for spray and light access. He prefers to keep skirts very low so that soil moisture is preserved.

HARVESTING

And yet another trial is underway in this area of the farm; Jaff is currently assessing the use of ethapon. He suspects that the chemical impacts yield so this year he sprayed one block with ethapon and skipped the next. After next year’s harvest, he’ll have some concrete results upon which he can confirm or deny his theory.

Jaff anticipates confirmation of his suspicions and is already planning forward; if he doesn’t spray ethapon, the nuts will all have to be knocked out of the trees (about 70% of the crop drops if you use ethapon). Labour will be reluctant to harvest (just like most cane cutters shy away from cutting green cane) and Jaff will have to pay more per crate. A higher yield will justify this higher rate though.

Another change Jaff made this year was to ‘compress the harvest’; he employed more people and got through the job in record time. This resulted in three benefits for next year’s harvest: 1. Pruning did not encroach on flowering so flowers have not been disturbed or damaged at all, 2. Pruning was done properly with no time pressures 3. the trees have some time to recover from the trauma of pruning and move in to the flowering phase in a more stable state. We look forward to hearing what Jaff’s results are …

Those of you who read Jaff 3’s story may remember the in-field scale that works so well for him. Jaff 4 was using the same scale but sent it back to the supplier yesterday … for his labour, it just doesn’t work so well. For some reason, they feel that it ‘robs’ them. Jaff got tired of the fighting and, next season, will revert back to bags. He knows it is not as accurate as the scale but his labour knows that they are only paid for full bags. Horses for courses …

PROCESSING

So I have mentioned that Jaff is one of the country’s top growers in terms of unsound kernel but now I need to let you know exactly HOW good … he is the 2018 National Grower of the Year for his group. It is the first time that an Mpumalanga farmer has received this accolade. Jaff’s unsound kernel is just 0,03% !! As we know, processing is the point at which any defects can be removed so let’s learn from what he does in this department:

Sorting table 1 removes nut borer, mouldy and rotten and immature nuts.

A water bath is then used to identify further nut borer and immature nuts.

Sorting table 2 is used to further refine the quality and Jaff says the imperfections are far easier to see on a wet nut.

Jaff says that only the first 8 or so tonnes in the season require much attention, from then on the girls on the tables have very little to do. Even though older and immature nuts are sorted out of the main batch, they do not need to be thrown away – there are markets for all grades.

After that, the nuts go into the drying bins which, on this farm, are old tobacco ovens. The nuts are placed in here loose, with unheated ambient air circulating through. Each bin takes 8 tonnes and Jaff has 10 of them. It takes 12 days to dry a batch. If he added heat, he could get through the drying process in 5 days.

Thank you “Jaff” for having me on your farm and in your home and for teaching us all about how to farm macs to such a high standard. Thank you especially for sharing all the many areas in which you are still learning – we are encouraged that even the most accomplished farmers are still discovering how best to grow these delicious delicacies. I look forward to hearing all the outcomes.

PS: This ‘Jaff’ was happy for me to publish his name … like we used to in SugarBytes articles … I declined as I want all farmers to be assured of anonymity when participating in TropicalBytes, but if any of you would like to hazard a guess, I’ll be happy to verify it. 😊