Would you like to stay equipped with the very latest TropicalBytes articles as they are published? SUBSCRIPTION IS FREE, just send me your email address so I can get the links to you (one approx. every two weeks). debbie@tropicalbytes.co.za

| Date | 29 May 2019 |

| Area | South Coast, KwaZulu-Natal |

| Distance from coast | 30 to 40 kms as crow flies |

| Soils | Predominantly sandy |

| Rainfall | 700 – 1000mm annually |

| Altitude | Av 600m |

| Temperature range | 13 – 27’C, although it has been known to go down to 5’C |

| Varieties | Beaumont, Nelmak 2, 816, 741, 788, 814, A4, A16, 863, 344, 842 |

| Irrigation | Trees are hand watered until they come in to production and then irrigation is installed. |

For our regular readers, two stark differences will be apparent as you begin this article: The first is that the farmer is unidentified. Unlike previous articles, where we have named the farmer visited, and presented his farm and family history, from now on the farmers will be known only as Jaff – which is an acronym for Just Another Fantastic Farmer, in line with our new policy of respecting the privacy of our top farmers. By the end of the article, many of you may figure out who it is because the farmers are no less real, and the content no less factual, than it was before. As a way of identifying which Jaff is being discussed, eg: when farmers contact me to request direct contact with a farmer, we will number each Jaff – ie: this article is on Jaff 1. Our sincere hope is that this anonymity will open the doors of some of our VERY best farmers who have been reluctant to ‘fly above the radar’ thus far, as it is now possible to give back to the industry in which you have excelled, without identification.

The other big difference with this article is that it focuses on macadamia farming. Our last article introduced the crop and this is our first farmer story.

Let’s meet Jaff 1 … a second-generation farmer whose main crop has been sugar to this point. Over the past 20 years they have transitioned their farming enterprise to predominantly Macadamias. Jaff says the crop is exciting but the industry here is so young, everyone is still learning – and he includes himself in this, despite the crop having been on their farm for so long. When we consider sugar has been an active industry in South Africa since the 1800s and macs have only really been brought into focus in the last 20 years on the South Coast there is so much scope for learning …

VIEW ON THE INDUSTRY

The obligatory conversation on the future of the mac industry kicked us off and centred on China’s role in the landscape: Jaff explained that the Chinese expansion is a government poverty alleviation programme whereby thousands of small-scale farmers have been given trees which they then need to cultivate independently. The results of this arrangement are very different from what they would be if large-scale, independent, commercial operators were behind the growth. Being mostly hilly, the Chinese landscape is also not ideal for mac orchards. The logical assumption now is that output from these trees will be limited, and quality may be lower, which will affect the way this supply impacts the market. Being high quality producers, SA macs may not even be in the same arena.

Although the Chinese have become accustomed to this higher quality, let’s say they are happy with their locally grown macs and draw from that supply – all it would take is a campaign geared to increase Chinese consumption marginally and, because of the sheer size of the Chinese population, the local produce would be drained and imports remain necessary. The SA Mac Association is mandated with stimulation of future demand and are working on these projects already. We also can’t forget that many countries have not even been awoken to the creamy, delicious nut yet – the market potential is certainly vast.

All in all, Jaff is, justifiably, very bullish about the future of the SA mac industry.

OTHER CROPS

About 6 years ago, Jaff got into Essential Oils and now has 120 hectares of tea tree, rosemary and rose geranium in the ground. These grow well in the sandy soils and Rose Geranium is being used to intercrop between the younger mac trees.

Rose geranium sharing space with brand new mac trees

Rose geranium sharing space with brand new mac trees

Contrary to most players in this industry, Jaff is happy to share what he knows about growing this crop but cautions that the size and stability of this market is questionable, placing a risk on investment therein. Having chosen the organic route has helped them contend a slightly smaller supplier base but it does come with its challenges in terms of farm management and the administrative demands with regards to certain accreditations associated with Essential Oils.

Once the essential oils market settles and shows potential as a viable and sustainable option for our Tropical growers, we will bring you more detail on the success stories of this crop.

SOILS

This farm is predominantly sandy with a low clay content in the soils. The soil depth also tends to be fairly shallow in most areas. These features affect the way Jaff farms as he begins to cover, in land prep, below.

LAND-PREP AND PLANTING

Jaff emphasises that land prep is unique to every farmer and every farm, in fact, it should probably be different for every field, if necessary. Here are some of the things Jaff does and why:

- Remove the existing crop and let the land rest. Everything here has been under cane for many years so the cane needs to be removed and the land rested for about a year.

- Correct pH imbalances. Intense agriculture can result in pH levels that cannot optimally sustain ‘life’. A good dose of lime and possibly gypsum will begin to address any imbalances and provide an environment in which essential micro-organisms can begin to flourish.

- Ensure soil is loosened. On flat lands, Jaff does not cross rip but he does use a four-furrow plough to kick off the process. This loosens the soil to a depth of about 600mm. When soil depth is insufficient (needs to be about 1,2m) Jaff builds up ridges so that the trees have enough accessible soil to establish good root penetration. On steep land, where terracing is required, and ridging not practical, they will cross-rip.

- Never cut corners in land prep. Jaff has learnt, through personal experience, that it is best to slow down and invest the time and money into quality land-prep. It can be expensive, but it is always worthwhile. The cost of doing it poorly manifests in many ways, eg:

- gradual yield loss,

- susceptibility to diseases like phytophtera,

- the cost (and other impacting factors) of fixing mistakes after the trees are already in,

- compromised farm management.

All these have a negative and substantial effect on the bottom line.

- Consider spacing carefully. This aspect is dependent on each farm’s individual situation:

- Size of farm: if it is a small farm and management is intense, trees can be well-managed meaning that more trees per hectare is viable.

- Water availability: Consider that droughts are inevitable and what those implications are for your orchards – fewer trees per hectare may be wise.

- Chemical penetration: efficacy is limited to reach so if your chemicals can’t get to where the challenge lies, they’ll be a waste.

- Management style: Each farmer is in a unique situation and has to consider how much they can take on in terms of pruning attention etc. Generally, less dense orchards are more suitable for low capacity management.

- Goals: everything is a trade-off between input and output. It is worth considering your goals, and what is required to get there, when planning spacing.

- Don’t go too wide – placing rows too far apart will also affect chemical delivery if the reach is too far.

Because of the unique circumstances of each farm, Jaff is reluctant to give a blanket recommendation but he has settled on a spacing of 9m between rows and 4,5m between trees giving him around 250 tree per hectare. This allows a 2m to 2,5m gap between the rows (variety dependent) when the orchard is mature which is sufficient to achieve effective penetration in a well-pruned orchard with suitable spray equipment. It also gives the trees good survival odds in drought conditions. He has orchards that are spaced anywhere from 10m x 6m to 8m x 4m and has therefore learnt through experience that, if the orchards are functional and well-managed, yield can be good despite small changes in spacing.

Sparse spacing may be better? The diagram above represents two orchards – the one on the left is spaced sparsely, at 10m x 6m. Over one hectare that would result in 160 trees – 10 rows, each with 16 trees. There are therefore 9 inter-rows, each one measuring 2,5m wide when the trees are at maturity. If each row is 100m long that equals 2250m2 of interrow and 7750m2 of potentially nut producing canopy. And this orchard would require 11 passes to spray (9 inter-rows plus the two outside passes).

The other orchard is densely planted, at 8m x 4m giving us 12 rows, each with 25 trees – 300 trees in total. This gives us 11 inter-rows, each with the same dimensions as in the first orchard. As the same equipment has to spray these orchards, the second orchard would have had to be pruned more aggressively to allow the equipment access. So, with two additional inter-rows, the total inter-row space of the second orchard is 2750m2 and the total potential nut-producing canopy is 7250m2, 5% less than the first orchard. You will now also need to make two additional passes (on the two additional rows) when doing any spraying or chemical / fert applications.

Although there are MANY other factors to consider and it may be strongly debated that not all parts of a mac canopy is nut-producing and not all varieties can develop such a large canopy (7,5m wide), it is definitely worth wondering whether more (ie: dense planting) is always better … In Jaff’s experience, the trees have been able to fill the space allocated and produce across the canopy, hence he is now following a less dense spacing that allows him to survive drought conditions better.

- Set contours precisely. A 0,5 – 1,5% gradient on the contours is what Jaff has found works well on this farm. A lesson he has had to learn is that water runs off macs far quicker than off cane and contours must therefore take this, as well as soil type, into consideration to avoid water and top soil loss.

- Consider Consultants. These professionals provide a full mapping service that covers all facets of the land. Every piece of land is different and you might be surprised at what the profiles are. I have had more than one farmer who has been saved a lot of expense through sound advice regarding what should, or shouldn’t, be planted in some fields. Jaff has found their advice and profiling worth the investment and recommends that you start small, experience the value and service yourself, before getting your WHOLE farm done in one go … which may be unaffordable.

- More about the actual planting process. Jaff digs a hole that is 300mm x 300mm x 400mm deep. If they are planting on terraced land where ripping has not been possible, they will dig a bigger hole, loosening a greater area for rapid root penetration. He mixes the soil from the hole with about 10kgs of compost that he has made from decomposed mac husks and matured chicken litter (it is very important that this litter is mature to prevent burning the roots). If it is a dry spell, he will incorporate 10 litres of hydrated Aquasol into the mix. He then replaces some of the compost-soil mix back into the hole, together with 5 litres of water. The tree goes in carefully and the remaining compost-soil mix goes around the tree. 15 litres of water is then applied. The sandy soils typical on these farms make the volume of water important but Jaff says that soils with a higher clay content may not require as much. After watering, an ample trash/mulch around the tree is important. Jaff is using cane tops currently but will use the tea tree waste from the still when he is no longer farming cane – any organic matter would work. The purpose is to create an environment suitable for microbial life – the activity of which benefits the trees.

Here is the “compost yard” where tea tree cuttings are busy breaking down.

Here is the “compost yard” where tea tree cuttings are busy breaking down.

ASPECT PLANTING

Planning an orchard needs to take the sun’s aspect into consideration but Jaff doesn’t believe it is terribly important and can be mitigated by good farming practices. This opinion is based on his results. “If you have the choice, do it. (sic: plant for perfect aspect) but contours and drainage are far more important issues and need to take precedence over aspect.” Of course, there are circumstances where aspect becomes a bigger factor eg: planting on a steep slope where sunlight is already compromised.

NURSERY

Jaff is passionate about fellow farmers recognising that the nursery is a key, integral part of getting the recipe of successful mac farming right. Whether you are buying in or operating your own nursery, every tree must be inspected thoroughly before buying / planting:

- stem condition needs to be healthy and undamaged,

- graft site condition – make sure this is not bulging,

- overall health of the tree,

- leaves (the colour thereof can indicate deficiencies),

- root system – mustn’t be penetrating bag,

- size of bags – must be big.

Low prices and desperate farmers are also warning lights; always be cautious of a low price. Similarly, recognise that desperation to get trees in the ground (can happen, especially when you are after a particular, less available variety) is a very dangerous state. Jaff says, “Realise that your rush WILL cost you in the long run. Slow down – it’ll be worth it.”

Jaff has his own nursery on the farm but warns his compatriots not to attempt it if they don’t have the time to manage it properly. He has up to 90 000 trees in the nursery at any time and this requires a well-trained, full-time nurseryman, with support staff. It takes 18 months to produce a mac tree. Jaff has been using Beaumont root stock and lately (in the past 4 years), he has started using cuttings as well. They are doing well but Jaff wisely says that this could be a result of a number of other factors besides the fact that they started as cuttings.

VARIETY SELECTION

Selecting varieties for your mac farm is a bit like selecting a rugby team for the ‘boks. You need a range of characteristics, they need to work together and be well-managed. Props (816) can’t be put on the wing (Beaumonts would be more this kind of player) etc. It also depends on where the game is (farm specific). In this operation, they have 11 varieties; 816, 741, 788, 814, Nelmak 2, A4, A16, Beaumont, 863, 344 and 842. Jaff warns against the temptation to expect varieties to produce uniformly in different situations ie: just because he has struggled with 788, doesn’t mean you will. Optimal variety selection is not a simple overnight decision, it takes years of trial and error. Here are some factors Jaff feels should be considered when deciding what to plant:

- What has shown success in similar soil, climate and water conditions as your farm. Ie: have a look at the neighbours.

- Spread production. From a management and cash flow perspective, it is important that your harvest is spread. Here, they enjoy 6 months of harvest by including some early (344, 788, 816. 741, 842), mid-season (A4 & A16) and late (Beaumont) varieties in the ‘basket’. This spread also means that spraying, fertilising and irrigation tasks can be spread over a more manageable time-frame.

- Hedge your bets. Although 816’s can produce some impressive nuts, Jaff’s 816 crop failed two seasons ago. This variety tends to be a bit of a finicky child – wonderful when it is content (it HAS to have water) but easily upset. It took two years for the trees to recover. Too high an investment in it could be a risky move. On the other hand, Beaumonts don’t always deliver the biggest nuts but they’ll see you through a dry spell and this makes them key players in a well-rounded team.

- Play to your strengths. Eg: A4 and A16 are very viney and because of this more delicate structure they tend to break and/or bend in the wind. Specialised pruning is important so, if you struggle with high winds or the thought of specialised pruning, consider this in your planning.

- Varieties behave differently every year. The best way of handling this reality is to ensure you have a broad and balanced spread of cultivars.

Jaff’s team going forward comprises 8 key players that he will rely on to keep him out of the ‘fired coaches club’. They are: Beaumont, Nelmak 2, 344, 816, A16, A4, 814 and 863. 344 is a variety he has had really good yield results from where few others have. His 344 orchards are older which may have something to do with it but they will definitely feature in his planning of new orchards.

IRRIGATION

Fully irrigated farms produce better but run at a higher cost. It’s a trade-off that each farmer personalises to his capacities. Jaff intends to equip his entire operation with irrigation eventually but is doing it gradually. For now, young trees are watered manually but by the time they come into production, the irrigation system is installed.

He has chosen to continue with the existing method of irrigating on this farm which is via microjets but does not exclude other options down the line. The advantage of microjets is that you can SEE it working. Low pressure powers the system and allows Jaff to use less water over a larger area; which is important in a drought.

When I raised the topic of fertigation, Jaff had a mixed response; he conceded that the system does allow trees to be pushed into production earlier but he is not sure whether the substantial investment required offsets the returns realised. He also knows that fertigation demands intense management – if you have the capacity for this, great, but if you don’t you may be limiting your scalability or increasing your requirement for (expensive) skilled management.

Technology is being embraced with the use of probes and software recommendations, all managed by specialists. Right now, the irrigation systems are operated manually but Jaff looks forward to the day when the systems are automated.

Jaff drops a final pearl in this section as he emphasises that mac trees need water when flowering. It is simple advice like this that often makes the difference between a bumper crop and an average one, a successful farmer and an average one …

A4s tend to be very ‘viney’ and easily groomed by the wind.

A4s tend to be very ‘viney’ and easily groomed by the wind.

PESTS AND DISEASES

Young trees receive their insecticides together with foliar feed. Each orchard below the age of 4 is sprayed four times a year. Another facet of this preventative administration is a dose of “hot sauce” spray, delivered every 2 weeks, to discourage hungry wildlife.

Once the trees mature and enter their first year of production (year after first nuts have been produced) they fall into the mature spray programme. Over the last few years, Jaff has enjoyed exceptionally low unsound kernel counts. This validates his current spray programme which incorporates the following principles:

- Do not overspray. Although it is tempting to be aggressive and thereby ensure everything is annihilated, the long-term consequence will be resistance with no remedies, leaving you totally exposed.

- Keep changing active ingredients. This strategy also helps prevent resistance. As the mac industry is relatively young, the chemical options are limited. Some biologicals are becoming an option and Jaff will include those in his programme going forward. He has realised the need to become a bit of a chemical expert in order to efficiently assess the selection available.

- Penetration is vital. Regardless of the rig you are using, make sure it is getting the job done, Penetration and full nut coverage is essential for effective pest control.

- Know your enemy. Be prepared – Aphids & thrips go after new growth. Thrips also enjoy flowers. Stinkbugs, nut borer and False Coddling Moths (FCM) are after your nuts. Scout accordingly, intensifying efforts from first flowering until you have picked up the last nut.

Thrip damage on an A16 tree – Jaff notes that this tree will have to be pruned back well

Thrip damage on an A16 tree – Jaff notes that this tree will have to be pruned back well

- Manage your impact on the good bugs.

- Only spray insecticides at night when bees are in their hives and insect activity is low (they are therefore resting in the trees and will be hit by the chemicals).

- Be aware of the residual life of the chemical you are using to ensure that you are not posing a threat to bees.

- Scout. Scout. Using scouting to direct your spray programmes, rather than product labels, cannot be over-emphasised. Scouting the week after you have sprayed will verify whether or not the exercise was successful. Rain, a badly-mixed batched or poor administration are highly probable factors that will inhibit efficacy of a spray. The consequence of not scouting, even a week after spraying, could be catastrophic. For stink bugs, Jaff has made the scouting task a little easier by building a specialised rig that has good lights and two spray guns. The team gets into the field way before dawn, places the white sheets down, sprays a site and then moves to a second site to repeat the process. They then move back to the first site and execute the count.

Traps, that are checked every week (during peak seasons), are used for Nut Borer and FCMs.

Evidence of nut borer

Evidence of nut borer

Here are some more gems regarding the activity of scouting and spraying:

- Don’t drop the scouting ball, even when you are harvesting.

- Don’t discount the value scouting offers to easily improve your operation.

- Carefully consider your method of application. Full coverage is essential for full efficacy and Jaff believes this is best achieved by using ground-based applicators that generate a swirl and get in through the sides of the trees. In having said this, it is very important that the whole tree is covered, with special focus on the top third, where insects rest at night. There are always exceptions as Jaff points out when he advises that steep fields are probably best sprayed aerially, especially in wet conditions.

This tree is suffering from phythophthera. This orchard has particularly rocky soils which often results in this condition. Jaff sprays a stem paint to treat the affected trees. He emphasises that you need to be vigilant as spotting the signs, and administering treatment early, improves the survival chances of sick trees.

This tree is suffering from phythophthera. This orchard has particularly rocky soils which often results in this condition. Jaff sprays a stem paint to treat the affected trees. He emphasises that you need to be vigilant as spotting the signs, and administering treatment early, improves the survival chances of sick trees.

Vervet monkeys are a pest to which Jaff has not found an acceptable solution – he estimates loses to be in the region of 15 tonnes a year as the monkeys strip trees when immature nuts are soft. The most frustrating thing is that they only eat 2 of the 50 they strip.

NATURAL PREDATORS

The value of employing (free) natural predators in combating (expensive) pests and diseases cannot be over-emphasised. But, if you are not this way inclined, the lowest responsibility is preventing harm to the rest of the eco-system. Jaff fulfils part of this obligation by thoroughly researching all the products he uses on the farm and has learnt that you cannot always trust the registrations so extend your research beyond the label and supplier documentation. The aim of this research is to establish the side effects on natural predators and the surrounding environment (eg: micro-organisms). Understand what it is you want to achieve from your spray programme and exactly what it is, that the products you use, do.

Jaff is just about to start testing a new root development programme based on environmentally-friendly, organic principles but even this will first be tested on 10 hectares. The results will then be assessed before a bigger trial is conducted. Again, the overall results will be assessed before the products are rolled out across the whole farm. This staged, careful approach could be valuable in terms of financial risk as well as environmental risks and is a very good strategy to employ.

Jaff has heard about a farmer on the south coast who is using bats to control nut borer. Apparently wasps are also an option. If anyone can give me more information on these farmers/projects, I would be most grateful.

FERTILISER

Jaff’s fertiliser programme is incredibly well considered. He invests in the advice of professionals – many, not just one – so that he can pick up discrepancies and question further. He then adds his own insight and experience to come up with a field-specific, carefully administered programme.

When the trees are first planted, he leaves them to settle for about 6 to 8 weeks. They then enter the standard programme designed for one-year old trees. Each year the programme changes but the annual requirements are always delivered in 4 to 5 doses, by hand.

At year 5 a full analysis of the orchard is done – leaf and soil samples are taken, and the results analysed by professionals. Jaff’s final plan is then put into the software programme he uses to run the precision farming tools he has in place. Seeing a USB device slotted into the tractor that is then directed to the specific field scheduled for fertiliser and to then see the that field’s specific requirements administered precisely is something to behold. Jaff has found great value in this hi-tech investment. Producing trees get fed up to 8 times a year with the menu usually comprising 5:1:3, 1:0:3, magnesium sulphate and Calcium Nitrate. In addition to this, the trees get lime and gypsum every year.

Foliar feed being applied on 4-year-old Beaumonts to stimulate flowers for next year.

Foliar feed being applied on 4-year-old Beaumonts to stimulate flowers for next year.

Further supplementation includes a flower initiation spray loaded with nut-set boosting nutrients like zinc and boron that will support the trees through this critical phase.

All spray and fertiliser programmes follow the individual cycles of each variety so as to support the natural tendencies of the trees and to manage the production spread to fit into the operations capacities.

PRUNING

In mac farming, this is a big topic and it seems that everyone is still trying to figure out the best strategy. Spending time with a farmer who has been learning for 20 years is valuable so here are some of Jaff’s views on pruning mac trees effectively:

- There are basic fundamentals that apply across all cultivars, and then there are variety specific characteristics that need to be catered to. The basic essentials are:

- Maintain height to under 5,5 to 6m

- Keep the skirt to about 1m off the ground

- Retain an access passage between rows for equipment AND sunlight

- Create windows to let light and chemicals into the centre of the tree

- Make sure there aren’t competing central leaders

- Let the trees grow just into their neighbour

- Massive prunings shock the tree and affect yield the following year so try to stick to a regular pattern. Jaff alternates a year of heavy pruning followed by a lighter cut the next year

- When establishing your own preferences, don’t be scared to over-prune– you may limit yield the following year but the year after that will get you back on track. 5 years ago Jaff conducted a slightly more aggressive cut and saw the positive result – he is now cutting a lot more out of the trees. At this time, he also learnt that each variety needs to be pruned differently.

This 19-year-old A16 orchard is ready for a heavy pruning. The access is becoming compromised and the trees are too high, too wide and too dense.

This 19-year-old A16 orchard is ready for a heavy pruning. The access is becoming compromised and the trees are too high, too wide and too dense.

- The variety specific considerations are:

- Prune with consideration to how the tree grows naturally – if there is already dense internal growth, make sure your pruning allows light and chemical access. If the tree is fairly ‘empty’ inside, then prune in such a way that stimulates fruit-bearing growth inside the tree ie: sunlight into the centre.

- Competing central leaders are not ideal – rather stimulate the growth of one leader that will become strong enough to carry heavier growth and be wind resistant. Other volunteering leaders can be trained to become fruit-bearing branches. Varieties like A16 do not really produce a central leader which makes pruning adaptations necessary.

- Some varieties are difficult to prune. Jaff’s staff have been taught to do what they can in support of the strategy for the variety concerned but, if they are unsure, they mark the tree and he comes through and attends to all the ‘challenging children’. There are no generic, ‘one-size-fits-all’ techniques.

Jaff will leave about 2 of the 8 water shoots here to develop into fruit-bearing branches.

Jaff will leave about 2 of the 8 water shoots here to develop into fruit-bearing branches.

I asked Jaff about the strategy of manually pulling down branches in young trees – he said it can be advantageous, if done right, or very detrimental if done wrong. Personally, he doesn’t prune anything before year 3 and believes you can train just as well by harsh pruning – an easier strategy than the hard work option of tying branches down. This opinion comes from experience – he has tried the tie-down route.

Just to show how important pruning is – Jaff does one main pruning AND 2 to 3 small ones every year!

Jaff points out that this 816 tree needs to be trained with the aim of stimulating more sideways growth

Jaff points out that this 816 tree needs to be trained with the aim of stimulating more sideways growth

EQUIPMENT & TECHNOLOGY

Although Jaff is young and progressive (they have one of the first precision farming fertiliser rigs in the area) he sees value in a conservative approach which allows others to ‘pay the school fees’. There is a balance between being the big-spending pioneer and the terminal follower. He advocates the strategy of gradually integrating anything new and peppering the journey with regular reassessments and realignments.

Jaff uses technology as a management resource in terms of allowing his team members to make independent decisions that are remotely monitored ie: people are empowered with independence but technology allows Jaff to ‘watch from a distance’ and take corrective action should it be required. Eg: data provided by each department is set against key measurements and Jaff is alerted when discrepancies require his intervention.

This precision farming rig houses delivers precise, field-specific fertiliser requirements.

This precision farming rig houses delivers precise, field-specific fertiliser requirements.

HARVESTING

Jaff sprays herbicide, when necessary, to clear an orchard floor for harvest. These Beaumonts require manual stripping.

Jaff sprays herbicide, when necessary, to clear an orchard floor for harvest. These Beaumonts require manual stripping.

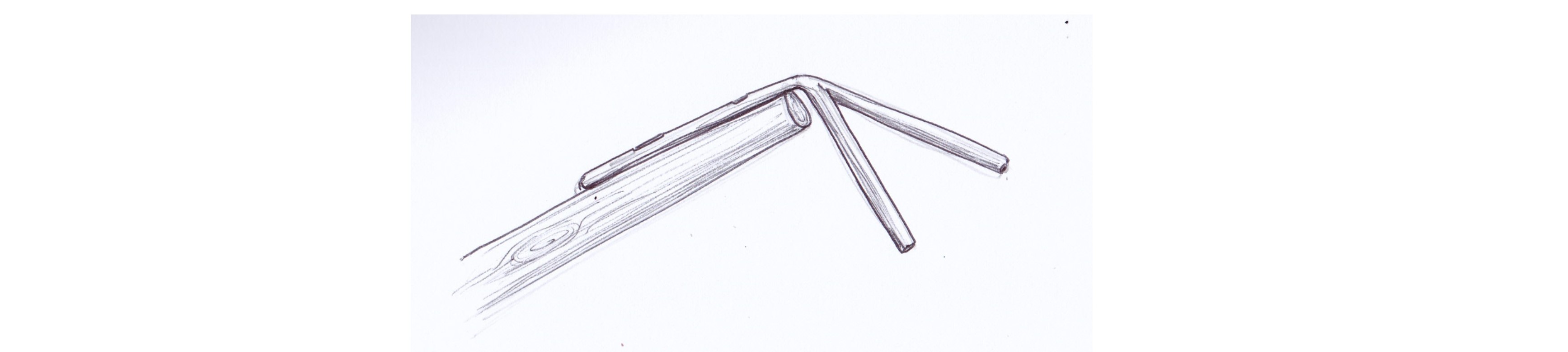

Because Jaff is concerned about the effect that ethapon has on subsequent production, he chooses not to use the chemical at all. This decision impacts harvest management. Theoretically all the nuts will eventually fall off the trees (varieties like 816, 344 and 788 drop well) so you could just leave them to do that naturally but this would make management difficult because you would end up with nuts and flowers on the tree simultaneously. Jaff’s strategy is to start stripping trees about 6 weeks after the first nuts start falling. Already (we are at the end of May now) he has all 344 and 741 orchards completely harvested. The staff use stripping sticks (illustration of the head below).

There are 90 people stripping and picking on the farm today. They put their harvest into measuring containers and then into a trailer and are remunerated daily (per task), not on volume. Stripping is considered a different task to picking. Each ‘unit’ can pick roughly 120kgs while stripping is about 80kgs per ‘unit’.

Nuts are never left on the ground for longer than a week (when they have fallen naturally) and stripped nuts are picked up on the same day. Records show exactly what came off each individual field and Jaff uses this information to refine his strategy going forward – which varieties/fields/fert programmes/spray programmes/ages etc produce well.

Immature flowers such as these, that are present during harvesting, will be stripped. The tree will reflower and this exercise assists in getting the production in sync. Stress initiates flowers and the recent cold snap, in this area, meant many trees shot flowers.

Immature flowers such as these, that are present during harvesting, will be stripped. The tree will reflower and this exercise assists in getting the production in sync. Stress initiates flowers and the recent cold snap, in this area, meant many trees shot flowers.

Harvest expectations in such a well-established operation may be interesting for new-comers to the industry so I asked Jaff about his; across the board, Jaff’s goal is an average of 3,5 to 4 tonnes per hectare. This is pulled down by varieties like 788 which are his lowest producers at 2,6 to 2,7 tonnes. This year he is very excited about the possibility of getting 3 tonnes from them. Countering with some heavy-weight expectations from 816 and 344, in the region of 6 tonnes per hectare.

Eighteen-year-old 816s being harvested

Eighteen-year-old 816s being harvested

PROCESSING

From the field the nuts go to the processing plant where they are dehusked, sorted and dried (using ambient air) to less than 10% moisture. It generally takes 10 to 14 days to reduce to 7 to 8% moisture. Further drying is required at the factory. As facilities to dry and hold nuts at this moisture (7 to 8%) is expensive, Jaff would consider modifying to heat-based driers in the future. Once the moisture is closer to 5% the nuts could be bagged and stored for a few months.

In order to keep accurate records on unsound kernel, only one variety is processed at a time.

SUMMARY

In wrapping up, I asked Jaff about whether he has made any mistakes we could all learn lessons from. The wry smile tells me to get comfortable … Jaff says he has been guilty of rushing and has planted out inferior trees because he was desperate to get them into the ground. “Perhaps I was just enthusiastic, but it cost me as I had to replant them all one year later.” Mistakes like this is why he emphasises the value of slowing down and thinking things through. “I have also had to redo beds that have suffered severe wash away because the contours were cut too steeply.” Now Jaff focuses on careful planning – this starts in the office, with pen and paper, moves into the field to consider the realities of the environment, and goes back into the office to combine the theory with reality. Eventually, after careful consideration of specialist advice and detailed mapping services, the field prep will begin. “Skipping steps or taking shortcuts will always come back to haunt you”, warns Jaff.

On the flip-side, Jaff has also made the mistake of moving too slowly; black death (fungus) got into the nursery a few years back and no one reacted fast enough. Before they knew it, all the stock had been wiped out. Had they reacted sooner, it would not have been such a severe setback.

It is through experiences like these that Jaff qualifies himself to deliver some intense advice: he feels that, generally, mac farmers could improve their long-term prospects by being more meticulous and tightening up on management. Currently, the reality is that mac prices are good. This can lull growers into a false sense of security which manifests in things like inaccurate or no record keeping, corner-cutting (like minimal scouting) or general short-sightedness. He implores farmers to set themselves goals that they can measure results against and then manage in a way that those measurements are possible. Continually reassess what you are doing and how it can be done better. Basically, as bank balances rise, effort, or the need to improve, tends to recede. By setting measurable goals, farmers can break this free of this trap, continue to improve regardless of current prosperity. Long-term, this is the only way to sustain the industry.

Jaff is grateful that he has set his goals around the development plans he has for the operation; they are ambitious and, to achieve them, he has to keep a careful eye on everything, constantly looking for ways to lower costs and improve performance.

Thank you, “Jaff” for all your insight and transparency, for being brave enough to open your doors and kind enough to allow TropicalBytes to share your knowledge and expertise which will equip other farmers for excellence and success.