Never have I been so pleased to have followed someone to their home. I met Thulasizwe and his family on the tar road, not far from the Sezela offramp and we drove on dirt or more than 20kms from there. It went on and on and on … I definitely would have doubted myself had I been alone. Once at Phathokwakhe – I was greeted by an authentic African farming scene: chickens running free, cattle, horses, pigs, goats, sheep and a very large and impressive veggie garden and orchard. It was so busy and organised – everyone seemed to have a purpose and focused on getting things done. Out of the car I’d followed emerged Thulasizwe (hence forth Thulas), Valentine – his wife and Thula – his son. When I managed to focus (I am easily distracted by all things ‘farm-life’) we went up to the office and began the interview.

| Date interviewed | 30 May 2018 |

| Date newsletter posted | 15 June 2018 |

| Farmer | Thulasizwe Ngidi |

| Farm | Phathokwakhe – farm is named after his father and means Looking after your Own |

| Area & Mill | Sezela |

| Area under cane | 307 hectares |

| Cutting cycle | 18 – 24 months |

| Av Yield | 2017 – 90 tonnes per hectare, down from previous average of 120t/h |

| Av RV | 12% |

| Best Yield | 167 tonnes per hectare. N12 at 24 months – cut in November 2016 |

| Best RV | 15% |

| Varieties | N12, N29, N39, N48, N58 |

| Distance from coast | 12 kms |

| Distance from the mill | Ave 25kms |

Thulas was born and bred in Ndonyane – St Michaels Mission from a subsistence farming family. His parents had a 10-acre plot on which veggies, potatoes, mielies and beans were planted. After matric he obtained a 3 year National Diploma in Public Health and qualified as a health inspector in 1979. An opportunity arose in 1997 when Illovo subdivided one of its large farms, named Mgayi, up into 14 smaller farms and offered previously disadvantaged black people the opportunity to apply to purchase them. Thulas’ brother, Sifiso, was excited to get involved and convinced Thulas to apply with him. Although they did not have previous cane farming experience, they applied and were both approved. Illovo equipped the farmers in terms of industry courses and a mentor (Vince Drew), Cane Growers and SASRI offered some in service training but beyond that, they were on their own. The 14 new farm owners had a communal hostel to live in but no farm houses or equipment on the individual farms. The size of the farm was not big enough for the family to live on its proceeds alone and it was for this reason that Thulas continued to work as a health inspector. By doing so, he was able to plough all the farm’s returns back into the farm. Valentine was a Life Orientation and Geography teacher; she and their 5 children lived in Umlazi where they were attending Model C schools. Thulas felt that it would not have been in their best interests to uproot them to the farm. Through commitment, dedication and hard work, he managed to buy one of the original 14 farms from his neighbour in 2003. Another 7 years of working two jobs and enduring much separation from his family and he eventually made a commitment to full time farming and simultaneously bought another 2 of the adjoining farms in 2010. This was a big year as his homestead on his farm was also completed.

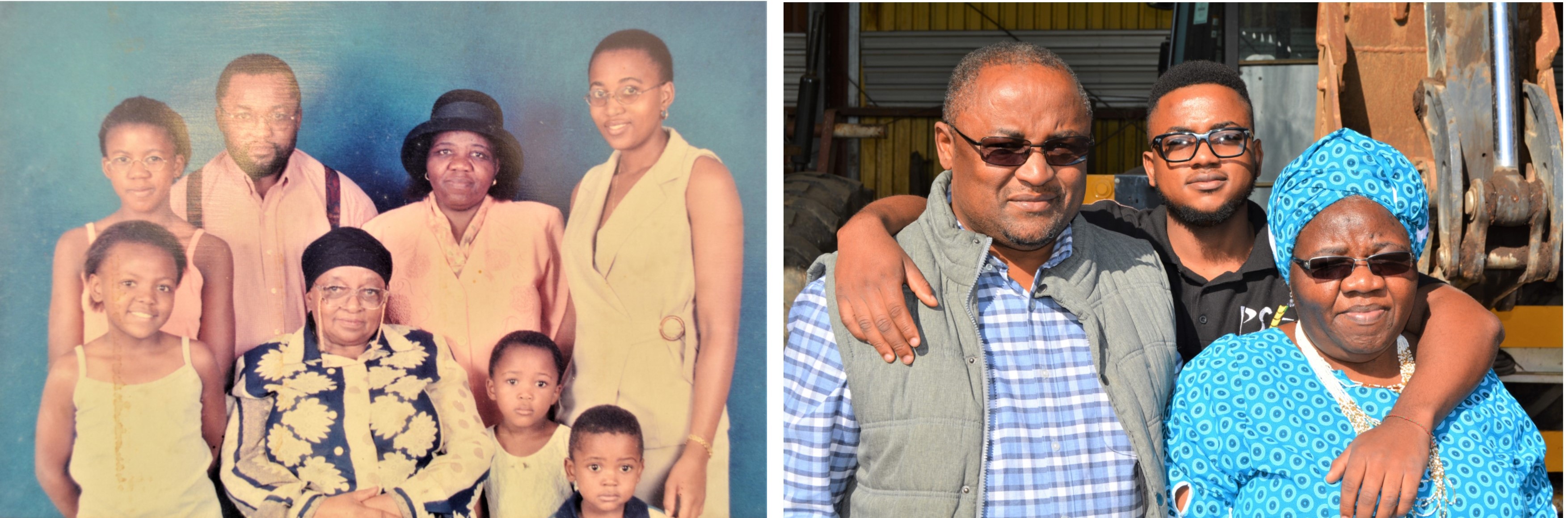

On the left is the Ngidi family, back in the late 90’s. Back row: Zethu, Thulas, Valentine and Nokuthula. Front row: Sthokozile, Grandmother- Thulas Mother, Sanelisiwe, XXXX and Baby Thula. The photo on the right pictures Thulas, no-longer-a-baby-Thula, and Valentine today.

Phathokwakhe now comprises 4 farms, all adjoining, totalling 409 hectares – 307 of which are under sugarcane. It has come a long way since 1997 when the plan was for these new farmers to subcontract most of the activities to service providers. Slowly, they all managed to become self-sufficient and today Phathokwakhe boasts an impressive staff compliment and fleet of equipment able to cover all its requirements as well as provide replacements when something requires repairs. That’s one thing Thulasizwe would like to have: a full-time mechanic – this would eliminate the need for expensive, ‘stand-by’ equipment.

Some of Phathokwakhe’s equipment

Some of Phathokwakhe’s equipment

So, what varieties grow here?

Initially, there was only N12 and N376 across most of Mgayi. When Thulas began here, he was told that this was the land of N12 and it is still his primary choice. If other varieties do prove viable, he still wouldn’t give it more than about 35%. Currently, over 80% of the farm is N12, although he has N37, N39, and is trying N48 and N58.

Here we have, left to right, N39, N48 – planted in October and N58 at 7 months old.

Here we have, left to right, N39, N48 – planted in October and N58 at 7 months old.

N29 has been a bad experience: when Thulas was advised that this was an excellent variety, he went ahead and planted substantial hectares and, after 4 cuts, it started to decline and develop rust, leaving him facing the expense of premature replants. When he compares this to the N12 fields that are over 30 years old and still producing handsomely, he is wary of venturing into anything supposedly ‘excellent’ prematurely. Now, he insists that he will only plant new varieties extensively after someone else has cut it 10 times and still recommends it.

N39 is also not scoring many points: on this farm, it is appears to lack stamina and be susceptible to Eldana.

This lead us onto the discussion about when to replant: “If a field shows declining yields over two consecutive years that are not explained by any specific issue – for example a fertiliser issue or drought – then we consider replanting it. Age is taken into consideration but old fields that produce well are not unduly replaced,” explains Thulas. As a recently interviewed farmer placed importance on seeing visible lines in a field because of application rates, I asked Thulas about this: “It doesn’t matter if you can’t see the lines, experienced staff are very good at accurately applying all the fertilisers and herbicides. We apply fertiliser from tins anyway, scattering them over the field in an arc.” When ploughing out, our focus is on worse producing fields.

This last season saw Phathokwakhe average yields drop to around 90. “I feel bad complaining about this respectable average but I’m used to getting above 100 and I have not managed to figure out why the yields have dropped. We had good rains last season.” Thulas is running through his yields per field and more than a few 130’s come up … I can’t help thinking that he is being conservative in his yield estimate. I keep this in mind when I ask about sucrose levels: although his best ever has been 15%, the average is closer to 12%. “Last month, the mill phoned to tell me that one of my fields had a 14% RV” says Thulas, justifiably proud. I wondered how much ripeners were responsible for these high sucrose levels and Thulas explains that that hasn’t been an option in the last 2 years, “We usually link up with Umzimkulu but, due to aircraft availability problems, aerial ripening has not been offered lately.” He goes on to say that he really hasn’t noted a marked drop in sucrose levels without ripening – this means he will reserve the expense for first cut fields only, when the mill opens early. ie: March.

Something I came to realise very early on in this interview was that Thulas does not confine his operation to rules and nothing is done ‘just because’. Everything is done for a reason, or many reasons, and those might be different for every field or every situation. My job of finding underlying factors for success becomes a little more challenging in this environment but it is a lesson in itself: Thulas’ advice would be to analyse what’s in front of you, together with all the history, facts and options and make decisions that work for that scenario.

How do you approach planting?

Preparing for planting actually starts when the last crop is still in the ground. Thulas explains; “It is critical to do RSD sampling on the last standing crop for all fields that will be replanted in that season. If I am practicing minimum tillage on a field then I will use Round Up when the cane is knee high, but sometimes I will plough out completely, especially if the field had RSD. Then we give the field a little rest – not too long – I can only afford a few months before that field is put to work again. But, there is always a break from sugar cane before replanting. Sometimes, while the cane is still small, I will use the space in between the rows for a quick alternate crop.”

Mixed cover crop of beans and mielies.

Mixed cover crop of beans and mielies.

Lime is applied several weeks before replanting, as per soil sample recommendations. It is standard practice that all harvested fields, that will be ratooned, get no less than 2 tonnes of lime every season. Thulas has an annual standing order for 120 tonnes of lime which he uses generously on all fields. To this point, he hasn’t done deeper soil samples but, today he collected the auger for subsoil sampling from Mr Joe Nkala (Extension Officer) to facilitate these deeper soil samples. These will tell him whether he needs to apply gypsum with the lime in future. Below is Thulas explaining to Bongani Shezi how to use the auger for deeper sampling.

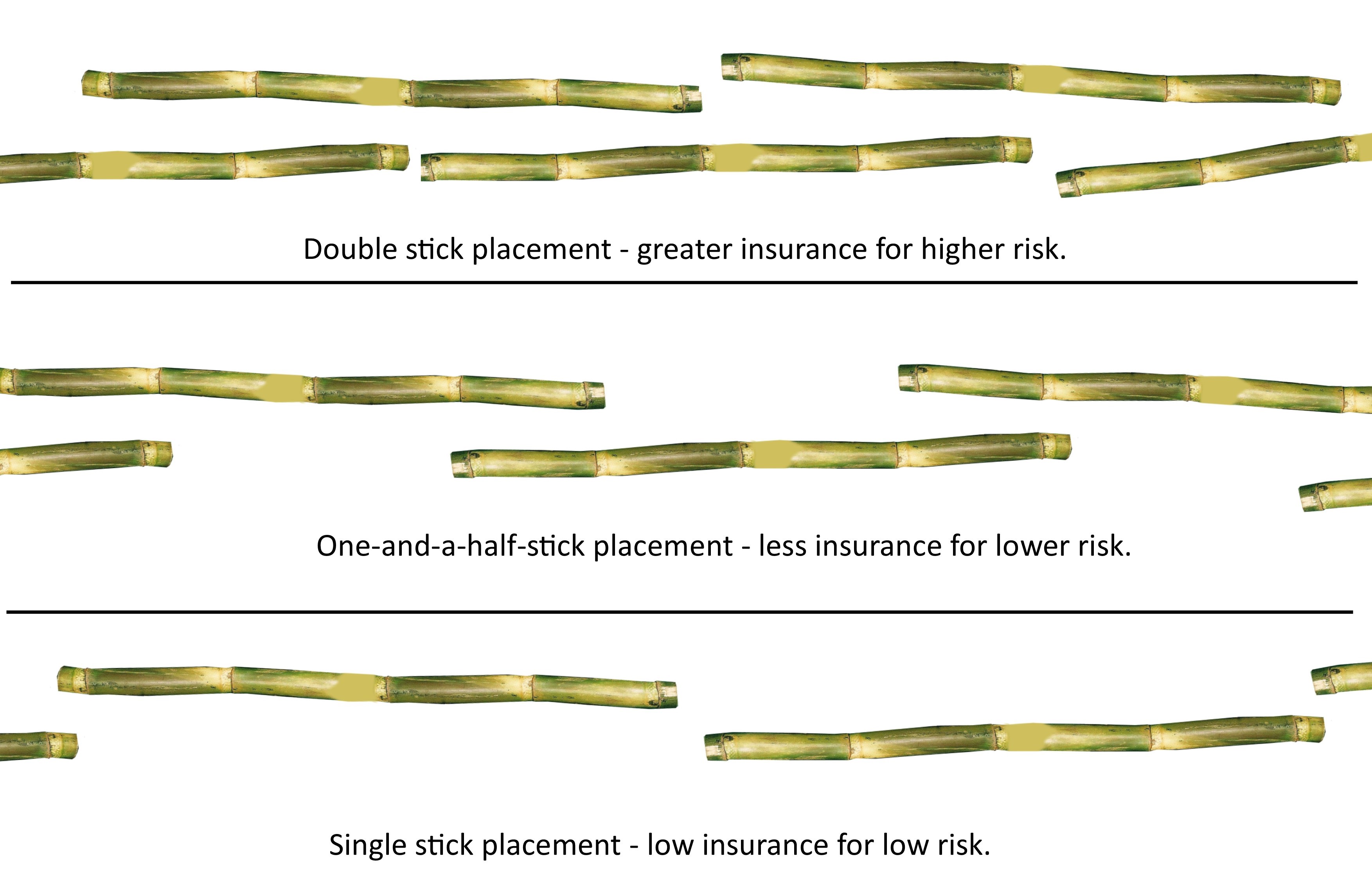

Thulas gets heat treated speedlings from Sezela Nursery. He plants these close to the homestead so that he can give them the water and attention they need. At around 18 months, they are used as seedcane. (The billets are spaced according to the ‘gapping risk) … Thulas hates gapping and spaces the billets according to the risk they pose: good quality seedcane, with a low risk is spaced further apart than a lower quality, that requires a measure of insurance against gapping.

Fertilisers and Herbicides:

Thulas buys from a range of places but mentions FarmAg, Farmer’s Agri-Care, Profert, Kynoch and Constantia Fertilisers specifically. One thing he plans to do, when Thula is more involved, is to do comparative analysis of yields per field and the returns from that field to assess the product used. The same would apply to herbicides. Thulas also considers financial implications and stock holding issues when buying; Kynoch assists with this because they allow him to buy before financial year end but only deliver in August. And their KynoPlus product has the additional benefit of limited volatilisation because it is coated.

So, once the field is ridged, cane is placed into the furrows and cut into billets, fertiliser (usually a 2:3:4, depending on soil samples) is placed into the furrow. Bandit, for the control of thrips, is sprayed onto the cane, through knapsacks, and the furrow is closed with a tractor-drawn closing tool. One man follows behind with a hoe, ensuring that the furrows are closed properly. This closing tool is the same as the one that one of our other top farmers recommended – Thulas says it saves him 18 units of labour. I have tried to isolate the implement from those around it in the picture below.

If necessary, a short-term herbicide is applied to eliminate any weeds that might be left after covering.

When the cane spikes, Thulas assesses the environment and applies appropriate herbicides and hand weeds if required. Top up fertiliser is also applied once germination is complete – usually a 1:0:1 or whatever the soil sample results called for. Each field is treated uniquely; blanket solutions are not employed.

Tell us more about the herbicides you use.

“This area of the operation is all about timing. If you miss a window when you could have used something gentle to handle the weeds that were present but instead, you come through when the weeds are now much larger, you have to use something stronger that will then have an adverse effect on the cane. That’s unfortunate and must be avoided at all costs.” Thulas gladly takes advice from Farm-Ag and Farmer’s Agri-Care agents. Generally, he mixes a cocktail that will contain pre-emergent as well as a chemical that deals with what has already emerged. “After this, we wait for the cane to canopy. The field may need another hand-weed just before canopy if there has been heavy rain but there are no hard and fast rules. The guideline is that it’s always best to deal with baby weeds, requiring less chemical, and while the cane is youngest, to minimise any damage.”

Are there any pests that require intervention to control?

This farm is positioned in the Hinterland, about 12 kms from the coast. Eldana is therefore a challenge but they’ve only ever had to spray twice, on carry-over cane. N12, if it flowers, becomes particularly susceptible. Growing cycles will be adjusted from 24 down to 23 months if harvest falls close to Eldana season.

We laughed about the “big pests” that eat the cane on their way out to grazing every day. Thulas says their saliva is like Gramoxone and the cane can be seen reshooting on the right.

We laughed about the “big pests” that eat the cane on their way out to grazing every day. Thulas says their saliva is like Gramoxone and the cane can be seen reshooting on the right.

Harvesting:

Burning is the norm although the cutters will trash if burning is not possible on a particular day or if there is a risk of a fire jumping; in this case a panel will be trashed to create a buffer.

Cut and stack is the method used and tractor-drawn trailers transport to zone where the cane is loaded into trucks with a crane.

After harvesting, gangs are sent in to hand-weed, spread the trash blanket and repair the channels carved by the cutters. If Thulas feels that a field is highly compacted, he will rip in the inter-rows down to 50cm (Happens -about every 3 years). If there is too much trash blanket, it will be burnt before ripping. This burning also deals with ‘trash worm’, which has also been a problem in the past but this is the first I had ever heard of this monster!? Thulas says it’s been better this year. It eats mainly at night and devours the baby cane leaves. Thankfully it only seems to affect first cut fields, in April and then to disappears shortly thereafter.

What support do you have in running an operation of this size?

Thula, Thulas’ 23-year-old son, is busy with his post graduate qualification. He is gradually integrating into the business and plans to make his this his full-time focus as soon as he graduates. Valentine, who retired last year, also helps with admin. Although Plan-A-Head software is loaded, it’s not fully utilised: it is used primarily for wages. The majority of farming records are done manually and on Excel.

Phathokwakhe has a soccer team that competes against local teams. The day I visited, their kit had just been washed. The picture illustrated again how well the people on this farm were on ‘one team’.

Phathokwakhe has a soccer team that competes against local teams. The day I visited, their kit had just been washed. The picture illustrated again how well the people on this farm were on ‘one team’.

There are approximately 62 semi-permanent staff. Thulas does what he can to keep the seasonal cutters employed and uses those willing for other tasks on the farm. Most of the cutters are from the Eastern Cape. They are paid per tonne when cutting, and per day when doing other work. Thulas wishes he could pay his staff more and tries in many ways to lighten their load, including farming pigs to feed them, paying their portion of UIF as well as paying for a funeral policy. All staff also have company-funded provident funds, which Thulas says, helps with retaining staff. “This season we have one intern –a graduate from Mangosuthu University of Technology – doing his in-service training for a year. This is a small contribution to youth skills development in the Sugar Cane Industry. He also receives a stipend. He will gain exposure that will hopefully help to secure permanent employment in the future,” explains Thulas.

This last one was a very bad season and has put the operation under dire stress. First time in 20 years they are actually paying back because of the low cane price.

In an effort to diversify, Thulas is planning to plant a couple hectares of macadamias per year. He also runs a herd of about 76 Ngunis and I grabbed the opportunity to photograph these beautiful animals:

Thulas prefers participative management and encourages his Indunas to contribute enthusiastically. There are four indunas: one overseeing the cutters, two cover herbicides, weeding, fertilising, fence and road repairs, and the last one is an office manager, handling much of the admin and record keeping.

From left to right: Madondile Ndabakayipeli (herbicides), Simon Nkonyeni (Cutters), Bongani Shezi (Admin) and Xolani Msani (Handy-man)

From left to right: Madondile Ndabakayipeli (herbicides), Simon Nkonyeni (Cutters), Bongani Shezi (Admin) and Xolani Msani (Handy-man)

Thulas relies heavily on these men, respects them and is very proud to work alongside them. His way with people is gentle, yet he is clearly a strong leader. His deep concern for individuals became very evident when we visited one of the loading zones … nothing was happening, despite the fact that the truck was not fully loaded.

Thulas drove in cautiously, already sensing that something was very wrong. We discovered the truck driver on the ground, incapacitated by an asthma attack. Thulas gently coached the man through some breathing but he needed a nebuliser immediately. Valentine and Thula had joined us on this photo-shoot around the farm, and we had two Indunas in the back of the bakkie so we added the truck driver in the front seat and bounced all the way to the local clinic, which thankfully, was on Phathokwakhe’s boundary. Both Thulas and the truck driver agreed that he had had about an hour left and, if we hadn’t ventured onto that loading zone when we did, he would have succumbed to the attack. In these kind of stressful situations, true leaders and good people show themselves and I was sincerely impressed by how Thulas managed this situation. You are an inspiration, Sir.

Look at the wonderful staff accommodation on Phathokwakhe! It is a part of the homestead area and Thulas mentioned that living in close proximity with the workers was intentional as it minimises security risks. He often wonders if the isolation of some farm houses doesn’t heighten the crime susceptibility.

Look at the wonderful staff accommodation on Phathokwakhe! It is a part of the homestead area and Thulas mentioned that living in close proximity with the workers was intentional as it minimises security risks. He often wonders if the isolation of some farm houses doesn’t heighten the crime susceptibility.

One staff placement I found very interesting was the Admin man, Bongani – he has come from the fields and therefore has a deep understanding of all the numbers and work he is recording. This gives him a better understanding and value to the business. This is a great example of empowerment that is a win-win for both Bongani and Phathokwakhe. Thulas emphasises the importance of knowing and walking the fields: when he first bought the farm, he would drive to the middle and walk away from his vehicle, in an effort to get to know the farm. Once, he was very grateful for the rudimentary map he had drawn while walking as it was the only reason he found his car again. He still spends a lot of time walking the lands; besides the benefits of acute inspection, it also keeps the Indunas on their toes!

As we chatted through the various challenges of farming and the reasons why Thula is pursuing a degree seemingly removed from farming, Thulas expressed his concern with land claims; ignorantly, I had assumed that black farmers would be exempt but that is not the case and Thulas’ sister actually sold her farm in a land claim a few years ago. Although Thulas would not be excited about it, he says that, after seeing photographs taken during forced removals in the early 1900’s he would never stand in the way of a legitimate claim on his land. Being compensated fairly would, however, be very important.

Again, Thulas’ compassionate nature shone through and I was eager to know where it came from. He explained that he was one of 10 children (more, if you count his half-siblings) and his father placed great emphasis on sharing in particular. They would often gather around isithebe to partake on a shared meal – literally off ONE plate. Each person has a turn and then waits for everyone else before taking your next mouthful. Valentine was also one of 10 and her sharing, generous nature was also overwhelmingly evident, especially when she loaded me up with fresh garden produce …

Pearls:

- Thulas says that discipline and hard work have been the key to his success, particularly financial discipline. He had never before seen the large amounts that came in when he first started receiving cane payments. It was so very tempting to spend it all instead of putting it back into the farm and allocating it in a disciplined way. He explained that that is the downfall of so many new farmers – they do not understand how expensive it is to sustain a viable farming operation, and how much financial discipline is required.

- Not only does a farm demand financial discipline, it also demands time. You need to dedicate yourself to the it: spend time walking the fields, keep detailed records, check operations and ask for advice. It’s just not possible to do it alone and there is always someone willing to help, just a phone call away. Thulas has found his Extension Officer, Joe Nkala, incredibly resourceful and helpful when it comes to advice.

- Not only is time important, but so is TIMING. It can make or break an agricultural concern.

- Thulas has been very involved in industry structures and, although the experience has been valuable, he’s ready to hand the baton on. He advises that a careful balance of your time is vital when considering involvement in industry bodies and organisations.

Thank you, so much, Thulas, Valentine and Thula for opening your hearts and welcoming me so warmly. Your hospitality was exceptional and I left feeling like a part of the family. You are special people indeed.

This view is seen from the best spot on the farm, and one that Thulasizwe uses as a retreat. From here you can see the homestead, the ocean and the mill.

This view is seen from the best spot on the farm, and one that Thulasizwe uses as a retreat. From here you can see the homestead, the ocean and the mill.