I am finding that more and more farmers are becoming reluctant to participate in SugarBytes interviews. Some feel that this platform shines a spotlight on their farm, exposing it to the government’s land reform programme. Others simply avoid any and all spotlights, regardless of the audience. The reasons are irrelevant and I do not judge anyone’s motivation for turning down an interview. Instead, I am infinitely grateful to those who do give me their time, and allow us all a walk through their operations with the simple purpose of unearthing any practices or policies that other farmers can take note of should they wish to improve their own farming operations. This is an incredibly selfless act on the part of these farmers and I need to highlight that to everyone: every article has taken an individual farmer’s energy away from his enterprise for around 5 hours. He has invested this, and a fair dose of his personal journey, in the industry as a whole, so that we can build this library of excellence and make it freely available to anyone who wants exposure and advice from the best in the industry.

Thank you, so much, to all who have gone before, and now – a very big thank you to Sam Sibiya, who welcomed me warmly to his small farm in Kearsney last Tuesday.

| Date interviewed | 22 May 2018 |

| Date newsletter posted | 1 June 2018 |

| Farmer | Sam Sibiya |

| Farm | B.S. Sibiya |

| Area | Kearsney |

| Mill | Darnall |

| Distance from the mill | 15 kms |

| Distance from the coast | Approx 13 kms |

| Area under cane | 116 hectares |

| Cutting cycle | 12 – 13 months, but working hard to extend that |

| Av Yield | 60 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 11,5% |

| Best Yield | 117 tonnes per hectare (N58 @ 18 months) |

| Best RV | 12% |

| Varieties | N12, N36, N47, N50, N52, N53, N55, N57, N58, N59 |

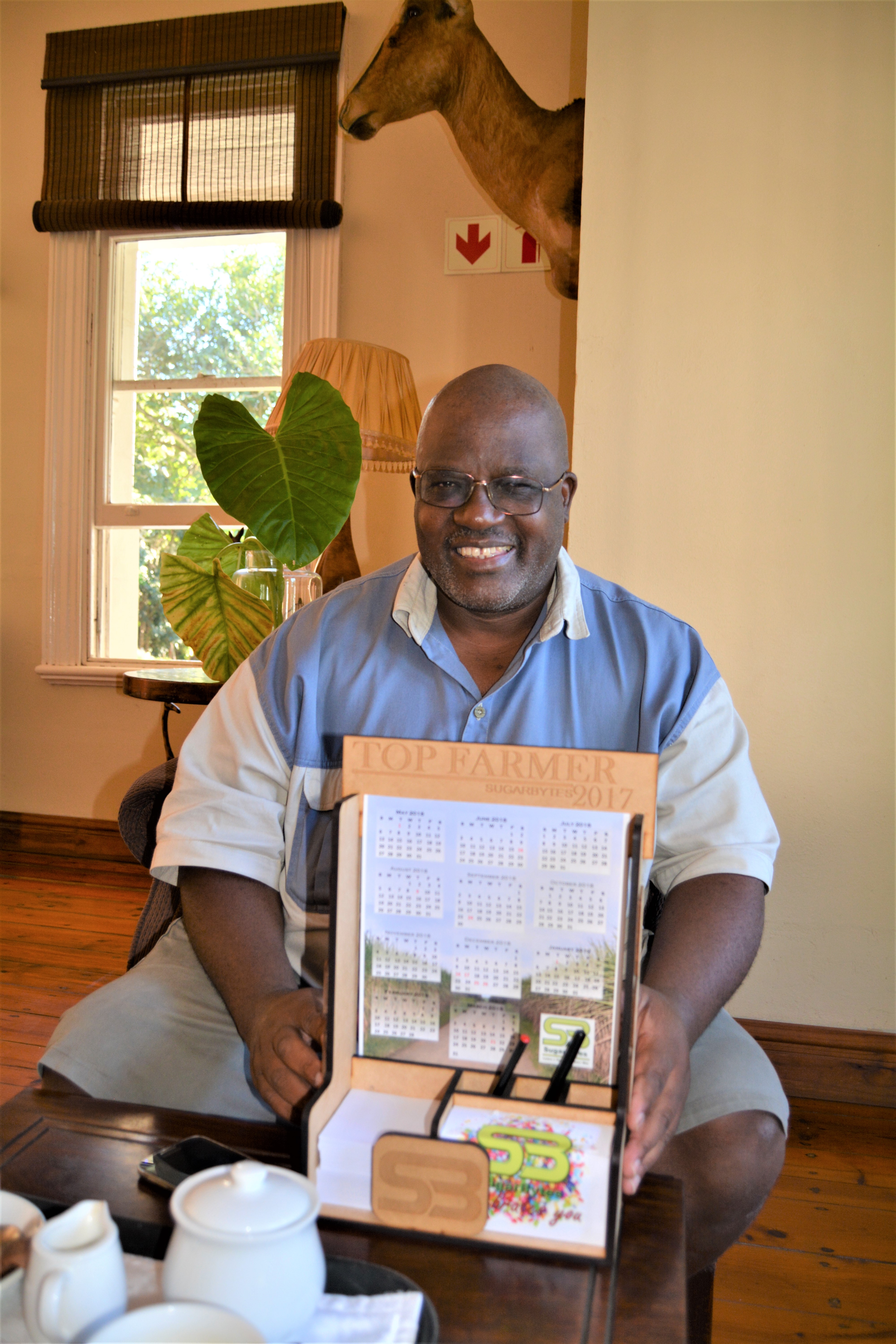

Sam Sibiya’s name was put forward as a Top Farmer by Adrean Naude who handles Extension in the Darnall area. We planned to meet at Kearsney Manor on the R74, about 25kms inland from Blythedale Beach. Sam was there, as promised, and we settled down in one of the Manor estate’s grand drawing rooms to discuss Sam’s farm, which neighbours this historically significant homestead. Being from Hillcrest area and having Kearsney School up the road, I was interested to learn that this was in fact the original site of the school, way back in 1938.

Sam was born and bred in this area. His dad was a cane supervisor for late Ian Smeaton. Sadly, he passed away when Sam was only 7 years old and Sam, his mom, along with his 6 siblings, had to move off the farm and into the local village. From there she pulled off a minor miracle in raising all these children alone.

In 1984 Sam got his first job as a task recorder for Tongaat Huletts under Brian Blake. It only took him 3 years to be promoted to estate clerk, and he relocated to Darnall to work under Raymond Ducray. From there he became an overseer, and not long after that an assistant manager on the same farm. In 1992 he became an estate manager with the responsibility of minding Springfield Estate.

His big break came in 1996, a year after Tongaat first launched their medium-scale farmer project. The crux of this project was to reform land ownership. They started by identifying promising black employees, within their own ranks, who could successfully take the reins to their own farm. Although the cost of this land was fairly reasonable, it wasn’t a hand-out and Sam had to finance the deal through Ithala and sign a veeeery long cane supply agreement.

Sam’s farm was 67 hectares, planted to cane. It didn’t take long to figure out that 67 hectares was not a feasible size and he eventually got the opportunity to add another 49 hectares to his estate, although it was not an adjoining farm. It was also in very bad condition – see pics below. The previous owner had deserted. He had his work cut out to get the land back into shape.

He would always welcome more land but these 116 hectares allow him to make a living and he is grateful and appreciative for the opportunity to be a self-employed farmer. If Sam could rewrite his life story, he may have chosen to be a teacher and it’s easy to see how this calm, quiet, humble man would have made a brilliant teacher. But Sam laughs and shakes his head, “No, I love farming. I think this is better.”

Sam prefers not to over complicate anything and keeps his headaches to a minimum by choosing not to own any equipment. Whenever there is a task for equipment, he simply hires the services of Brown Sugar Harvesters. Andrew Brown handles all harvesting, loading and transport for Sam. He also maintains the grass and whatever else Sam requires.

And so we started getting into the nitty gritty of Sam’s farming practices in order to see what makes this man successful … the most illuminated point I see is that he is a keen student. He is always watching and listening to his peers and brings home many tips from his study group. Sam is part of the Doringkop crowd and is privileged to have many great farmers there to learn from: Basil Oellermann, Piers Garnett, Anthony Balcombe, Myles Osbourne, Adrean Naude … and that’s only the names that have crossed the SugarBytes desk …

Plant cane

Sam takes a number of factors into account when deciding to plough out a field: yields, clarity of lines, diseases, and quotas.

Yields: If yields are down, below his average of 60 tonnes per hectare it raises a red flag.

Lines: If he can no longer see where a line is he runs the risk of inaccurate herbicide or fertiliser applications. Sam monitors his input costs like a hawk and has it down to a fine art. But not being able to see where the lines of cane are puts him at risk of either over applying and wasting money or under applying and wasting resources.

Disease: This is an easy one – Sam knows that P&D are on his side and follows their recommendations regarding plough outs.

Quotas: If the top three points are not an issue then it comes down to taking out the oldest fields, which Sam does so as to not fall behind the recommended 10% annual replanting guideline.

Sam used to follow a minimum tillage method and used Round-Up to kill the existing crop. He’s found his more recent method of ploughing and harrowing is better. A plough is put through the field to turn all the old stools upside down. Then the field is harrowed, usually twice. At this point, Sam leaves the field for a bit to see if anything is still rooted and, if necessary, uses labour to clean it out. He then limes. Regardless of soil sample recommendations, he’ll put in 2 tonnes per hectare of lime plus 1 tonne per hectare of gypsum. He believes these minerals give his soil a healthy foundation by correcting acidity levels and that allows microbes to build soil health naturally.

Although Sam has not fallowed his fields as a rule, it is a practice he wants to employ consistently and is now starting to investigate the best crops to use. So, for now, he moves straight on to ridging, and then planting – planting is done by Sam’s own employees rather than by a contractor. They lay double sticks in the furrow and cut them once with Jeyes fluid-treated cane knives. On to that, he places fertiliser. Currently he uses 2:3:4 (30). Along with liming, Sam places great value in this investment in the soil. It’s the only chance you have to get fertiliser directly around those new plants, which will be producing for you for the next 10 to 20 years. Sam’s men use Mayfield applicators and he emphasises the importance of checking calibrations carefully. He prefers to err on the heavy-handed side and gives the soil about 500kgs per hectare. Sam has been trying KynoPlus lately. It appealed to him because it is coated and releases its magic slowly. He is intrigued to see the results.

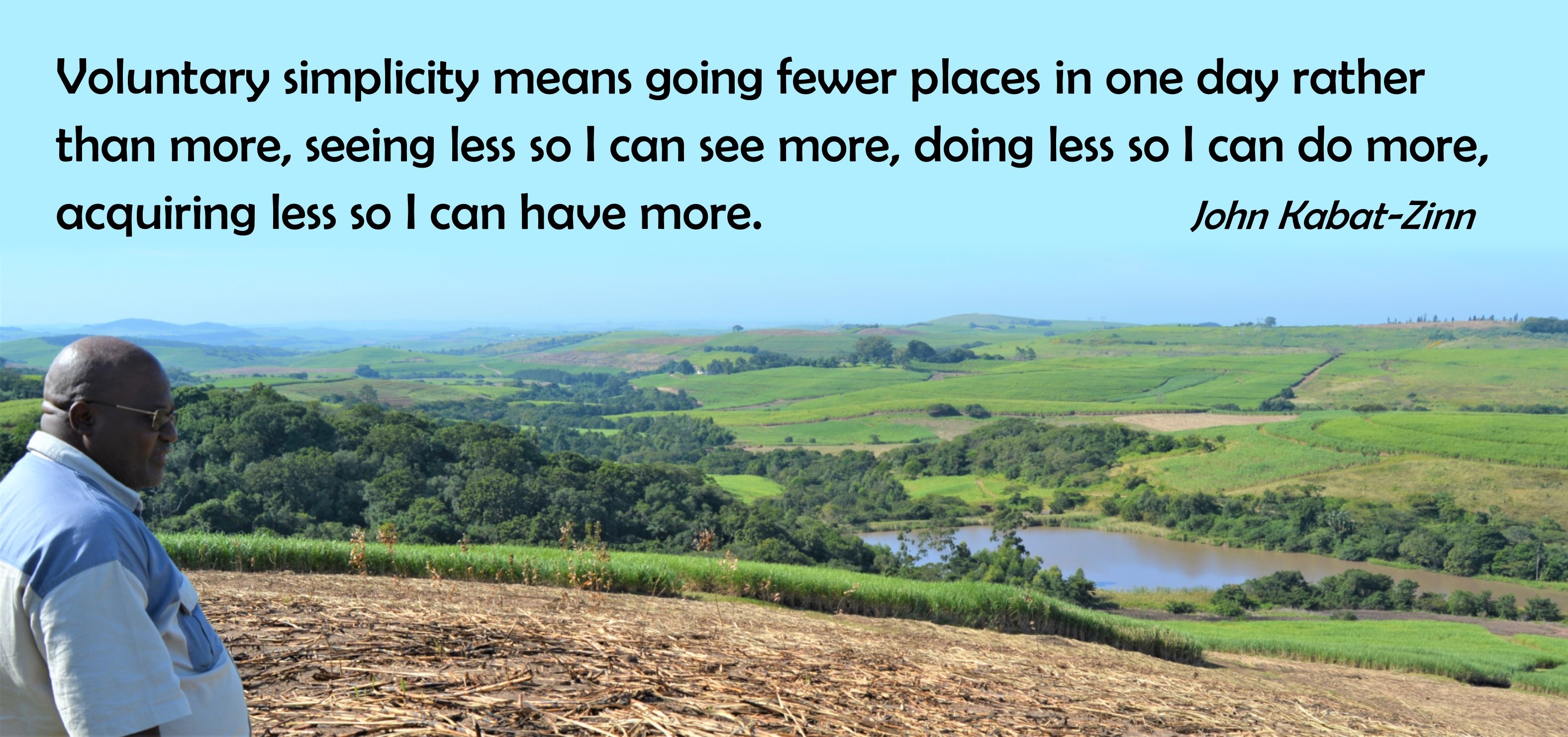

Sam’s farm has so many beautiful spots and an abundance of water, especially after the recent heavy rains (154ml so far, in May alone). His dam is particularly impressive and he allows neighbouring farmers to enjoy it with him.

Sam’s farm has so many beautiful spots and an abundance of water, especially after the recent heavy rains (154ml so far, in May alone). His dam is particularly impressive and he allows neighbouring farmers to enjoy it with him.

Varieties

Sam enjoys trying out new varieties and is currently assessing seven. He finds the SASRI information leaflets very informative – between those, and the advice of his neighbours, he decides what is worth planting. I love that Sam is humble enough to laugh at himself and admit how much he learns every day; “SASRI recommended N36 for valley bottoms but I tried it out on a slope. It’s growing well but I should have heeded their advice and kept it in the valleys.”

Sam, and his N36 at 11 months

Sam, and his N36 at 11 months

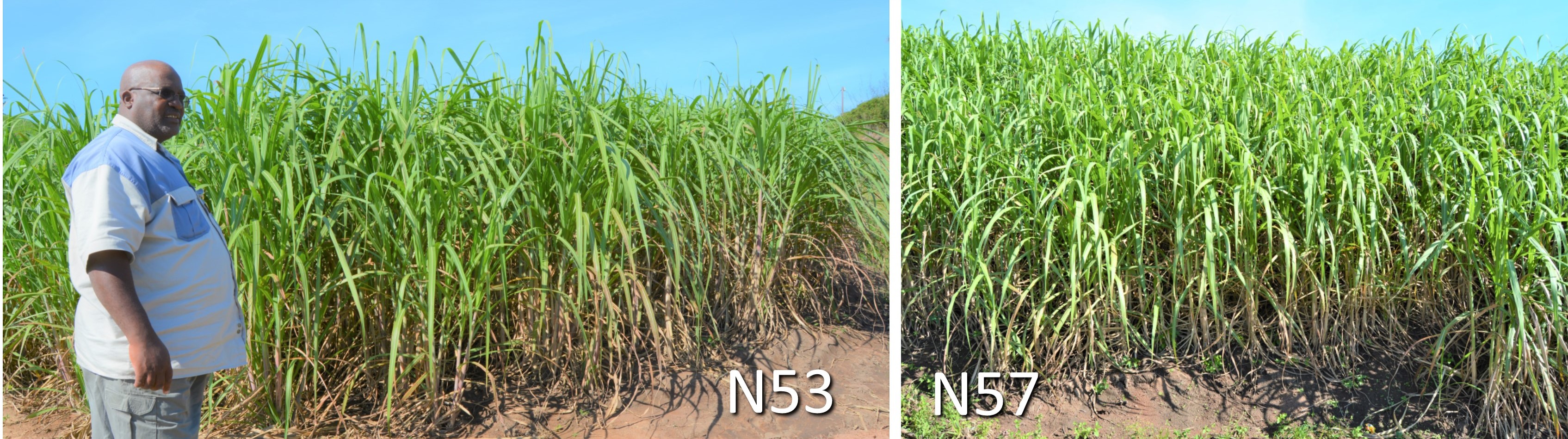

Another variety Sam is trying is N47, without much success. He says it’s like N12 but thinner. He’ll be sticking to N12 in future. He likes the look of N50 and N52 is also growing very well but P&D has warned him that Eldana becomes a problem when extending the growing cycle on this variety. N57 may also not be suitable for the longer growing cycles but this time, it is because of its tendency to lodge. Once it does this and roots grow from the nodes touching the soil, the sucrose drops. Sam’s current favourites are N55 and N58. He recently got 117 tonnes per hectare from an 18-month-old field of N58. It’s looking a lot like his trusty old N12. N53 & N59 are some of the other new varieties he is trying currently.

Once fertilising is complete, he covers the seed carefully, with hand-hoes. His men know that good coverage is vital as exposed cane will not make it.

Now it’s time to focus on the weeds: Sam believes that timing is the secret weapon when fighting weeds. Get that right and you can save money. He’s proven this by cutting his application rates in half and still getting the results he needs. Sam only uses pre-emergent herbicides. Currently, his recipe is: Acetaclor 900 at 3l/hectare plus Amatrene, also at 3l/hectare. If there is nothing green in the field at the time of spraying, then he uses 1/2l ‘wetter’ (also known as ‘beef up oil’) so that the herbicides stick. Sam mentioned that most other farmers apply these herbicides at double the rate he does but, because he has timing down to a fine art, he gets away with these low application rates, and saves a lot of money in the process. Sam says he doesn’t take his eyes off his fields. He is not distracted by other crops or a really large operation which means he can give this kind of attention. He spends almost 7 full days in his lands. Sunday mornings, he attends church, and then comes home, gets into his farming garb and quickly inspects all fields, starting with the plant cane, where his greatest investment lies.

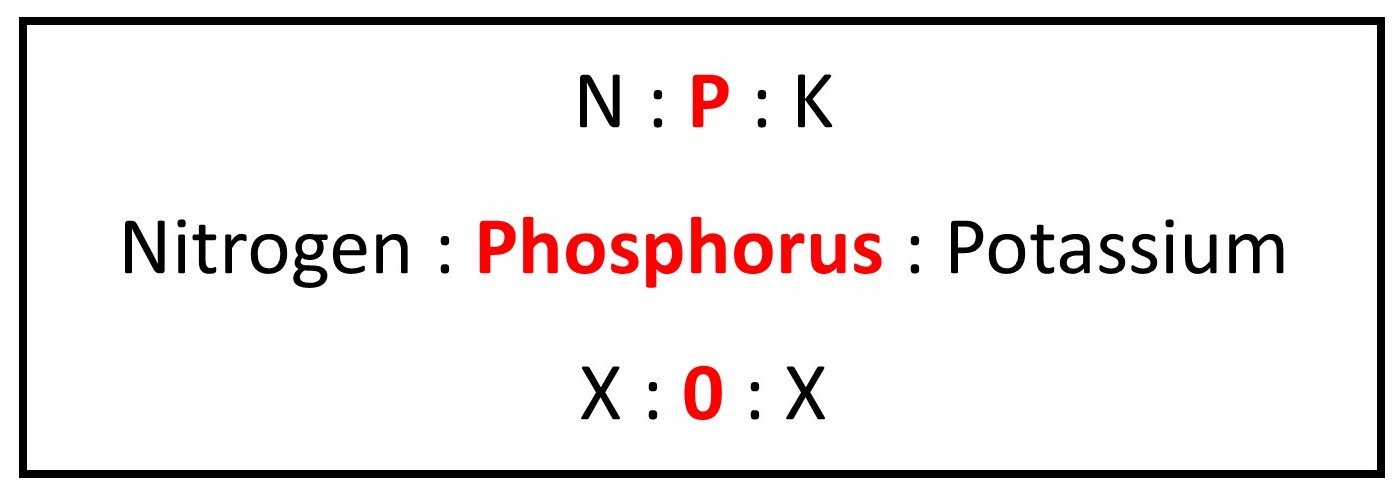

If any weeds dare raise their heads, hand weeders sort them out. When the cane starts to spike, a top dressing of 1:0:1 (or similar fertiliser) is applied at about 400kgs per hectare. Sam taught me something interesting at this point. He has learnt that any fertiliser applied above ground should preferably not have any phosporous in it …

Phosporous is a mineral that roots require and seek out so, by putting it above ground, you encourage roots to travel up rather than down. The fact that phosporous is relatively insoluble, and therefore doesn’t travel through the soil profile well, further exacerbates this problem.

From here, it’s up to the cane to canopy quickly at which stage Sam shifts his attention to maintaining the edges of the field where the sunlight encourages troublesome grasses to flourish. Sam says that, before you know it, these will have seeded and your fields will be struggling. Clean and tidy edges are vitally important to avoid expensive infestations.

No pesticides are used on this farm, simply because there hasn’t been a need. Recently a neighbour had some aphids and Sam noticed that they got into one of his fields too but they seem to have disappeared after the recent heavy rains.

Aphid damage

Aphid damage

Sam has heeded the council of his study group, who advised against ripeners. Sam simply follows a set schedule of which field is cut next. The norm has always been 12-month cycles but, last season, he stretched that to 13 months and would like to keep extending that as much as cash flow will allow, being happy to settle with half his farm on around 18 months. Sam listens excitedly when other farmers in his study group encourage him to get to the point when he will be cutting only 50% of his farm and still delivering his quota.

Sam uses Andrew’s teams to harvest and they burn the cane before cutting. Sam would sincerely like to move towards trashing his fields as he sees how much farmers in his study group benefit from this practice, but has patience in getting there. He keeps a careful eye on the contract harvesters though, ensuring that there are good low base-cuts and accurate topping.

Where the slopes allow, Bell loaders are used and, where it is too steep, cut and stack method is employed. Sam is strict about keeping the Bells out of the fields if they are too wet because of the severe compaction that takes place in wet soil. The trash that is left after harvest is carefully spread out in an even blanket.

Ratoon fields get slightly different fertiliser to plant cane. Here he uses either 5:0:7 (48) or 4:0:5 (48) – note, still no potassium – and applies it in spring, after the ratoons have spiked. As pre-emergent herbicides require moisture to get the chemical through the trash and down to the seeds, Sam holds back on spraying these until there is a little rain predicted. Anything that manages to dodge the herbicide is dealt with manually. As with plant cane, Sam is pedantic about keeping his fields clean until canopy and then diverts his attention to the field edges once again.

Left to right: Yandise Khophana, Sam’s right hand man, Msawenkosi Ndamase and Sipho Yalu. These chaps were busy spreading the trash blanket evenly; Sam likes to cover as much of the soil as he can. Whilst there, they sorted out the few weeds by hand.

Left to right: Yandise Khophana, Sam’s right hand man, Msawenkosi Ndamase and Sipho Yalu. These chaps were busy spreading the trash blanket evenly; Sam likes to cover as much of the soil as he can. Whilst there, they sorted out the few weeds by hand.

Sam seems to have a brilliant relationship with his labour; throughout the morning he regularly mentions his gratitude for their excellent work ethic and the assistance they give him. I had to ask how he manages to instil that work ethic … having been an employee for many years, he has insight from “the other side”. He explains that he simply treats them well and avoids having a threatening attitude. He disciplines when required but makes sure it’s fair and consistent. He believes mutual trust is important and pays according to government regulations. Being a reliable source of income is vital. Sometimes it takes an employee leaving you for them to learn that a whole loaf of bread in one go is not as good as a guaranteed, regular slice per day. His main guy learnt this the hard way a few years ago when he left Sam to work for a tender-preneur who didn’t last very long.

Sam, showing me the extent of his land

Sam, showing me the extent of his land

We briefly touched on our country’s current land claims saga and Sam has an interesting view on farmers wanting to stay “out of the spotlight” … he thinks that, with our president being the astute businessman that he is, he will not go the route of expropriating successful farms but rather reallocate lands that have been abandoned or have a chance at doing better under “new management”. This should be an encouragement to anyone wanting to fly their success under the radar – sounds like flaunting it might be a better plan …

What other “pearls” did Sam have to share:

- Timing. Doing things at the right time saves time, money and resources.

- Hard work. Work hard to know your farm. Sam insists that his labour could beat him at many things but he works hard to make sure that no one knows his farm better than he does.

- Be passionate. Love what you are doing. Get involved and the success will come.

- Be patient. Farming is not about quick cash. It is a long-term investment. People who come in looking for big bucks will be disappointed.

I loved what Sam said about farmers in general; “They are ‘plan makers’ – I admire this about my compatriots. They’re always working on plan B – they’re survivors and I have learnt to be one too.”

What a wonderful morning, spent with an incredibly modest yet infinitely competent farmer. Thank you for allowing us to get to know you Sam. You are an inspiration and an example for many and we look forward to seeing you reach all your goals for your special farm.