| Date interviewed | 19 April |

| Date newsletter posted | 18 May |

| Farmer | Jeremy Cole |

| Farm | Glen Rosa |

| Area | Dumisa |

| Mill | Sezela |

| Area under cane | 200 hectares |

| Other crops | 29 hectares macadamias and 200 hectares gum |

| Cutting cycle | 22 – 24 months |

| Av Yield | 100-105 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 12,5% |

| Best Yield | 202 tonnes per hectare (N51 at 29 months) |

| Best RV | 19% (after the “great fire”) |

| Varieties | N51, N12, N52, N55, N48, N39, N58, N376 |

| Distance from coast | 27kms |

| Distance from the mill | 43kms |

I am sure God created Jeremy Cole directly from the original FARMER mould. Being tall and strong, Jeremy fits the physical career requirements perfectly but it’s his genuine love for growing things and serene competence out in the land that completes the picture. Throw in a few natural disasters and near death experiences and we have a man who not only looks the part, but has lived it, and is so completely FARMER that it’s hard to imagine him being comfortable anywhere else.

The green thread is many generations long, but we’ll begin with Jeremy’s grandfather, who bought this farm from Bob Archibald in 1923. We marvelled briefly at how much has changed in less than 100 years since then when Jeremy recalls one of the stories he remembers his grandfather telling: it would take him a day and a half to walk to Umzinto where he’d fetch the post, sleeping in kraals along the way.

Doug Cole, Jeremy’s Dad was born on this farm. In the 1960’s it was split between him and his brother. As Jeremy’s only siblings are sisters who did not have an interest in the operation, he has inherited his Dad’s portion – Glen Rosa. His cousin, Kevin – also a highly successful cane farmer, is on the other portion next door. It seems there is no shortage of excellent farmers in this family … Richard Cole, whom we interviewed last year, is Kevin’s brother.

Glen Rosa is now home to Jeremy’s mom, Jeremy, his amazing wife Donna, Jenna (15 yrs), James (13 yrs) and Olivia (9 yrs), and TWENTY-SIX dogs! Yup – 26 … I wasn’t sure what to say to that piece of information … The Cole’s laugh and try to console me with the news that only 11 live around the house. Not helping. The rest are hunting dogs and, together with the ‘house’ dogs, they form a formidable homestead security force. Harbouring a healthy fear of dogs, I am completely ready to leave at this point but decide that this interview’s going to be a valuable one, so rather than run for the hills, we’ll move on to the task at hand …

As the words, “What soils do you have on this farm?” come out of my mouth I connect the dots … Glen Rosa!? Yup – so, was the farm named after the soil or the soil after this farm/area. Still not entirely sure that I haven’t just asked an incredibly stupid question, I move on swiftly … we talk instead about the fact that the local train staion is also called Glen Rosa … and here’s a stunning picture of the beautiful Coles standing under the station sign.

As the words, “What soils do you have on this farm?” come out of my mouth I connect the dots … Glen Rosa!? Yup – so, was the farm named after the soil or the soil after this farm/area. Still not entirely sure that I haven’t just asked an incredibly stupid question, I move on swiftly … we talk instead about the fact that the local train staion is also called Glen Rosa … and here’s a stunning picture of the beautiful Coles standing under the station sign.

A common misconception is that farming involves mostly plants and tractors. Jeremy knew better than that and, after matricuating from Hilton College, proceeded to acquire an allround education: he did a diesel mechanics trade at technical college, the SASA farmers course, a business computer course at Damelin and a Farmer’s Special course at the Industrial Training Centre in Mount Edgecombe. This included a foundation in wiring, welding, plumbing, building, refridgeration and more … the mischevious twinkle in Jeremy’s eye tells me how much he enjoyed these carefree student years but the late 90’s demanded that he focus his attention back on the farm. These ‘union-years’ saw many strikes and arson incidents and Doug needed Jeremy’s support in handling the delicate labour issues.

Thus began Jeremy’s shift at the helm of Glen Rosa. His temperate nature and affinity with the local community meant that he navigated this era well. Jeremy had grown up with many of the labourers’ children and has developed a life long friendship with one man in particular: Maxwell. Ironically, Maxwell comes from the Mbelu clan who are in the process of laying claim to many farms in the area. He, personally, has moved on though and is now the Southern KZN area manager for Sappi Saicor. He was a groomsman at Jeremy’s wedding and is godfather to his eldest daughter, Jenna. This friendship remains tight and has been extended to their daughters who are now best friends, in the same class at Scottburgh Primary. Jeremy’s realtionship with Maxwell has been a source of support and guidance through many contentious issues on the farm, from poaching to labour strikes.

Jeremy has many Zulu names but the most popular one is ‘Zinghotha’ which came about when he would disturb the workers huddled around an early morning fire so that the work day could get underway. When he was younger, he was known as ‘Gunqusa’ because he was always scouting around the labour compound to see what was for lunch. Donna laughs and says, “Nothing’s changed! And if he can’t get it at the compound, he makes it in my kitchen – there’s always a ‘Jeremy pot’ on the stove that I daren’t look into. There’ll be push pig or porcupine or walkie-talkies or something like that bubbling away.” This man is incredibly adept at living off the land.

While I was snapping pics of the cane cutters, Jeremy was snacking on a sou sou that he harvested from his extensive veggie garden.

While I was snapping pics of the cane cutters, Jeremy was snacking on a sou sou that he harvested from his extensive veggie garden.

Jeremy definately prefers to be outside, and admits to spending 99% of his time there. Donna helps him to do this by assisting with the business administration. Jeremy still handles all the wages – CanePro (specialist software) makes this a simple task. He also submits all the estimates, which he does completely on gut feel. “I seldom refer to the previous year’s figures and I’m never too far out,” he chuckles.

Jeremy definately prefers to be outside, and admits to spending 99% of his time there. Donna helps him to do this by assisting with the business administration. Jeremy still handles all the wages – CanePro (specialist software) makes this a simple task. He also submits all the estimates, which he does completely on gut feel. “I seldom refer to the previous year’s figures and I’m never too far out,” he chuckles.

Glen Rosa (inc the timber operation) employs about 85 people in season. There are two senior Indunas; one who handles most of the driving around and “things” (workshop, supplies etc) and another who handles people issues, ensuring that Jeremy’s instructions are carried out in-field.

Glen Rosa (inc the timber operation) employs about 85 people in season. There are two senior Indunas; one who handles most of the driving around and “things” (workshop, supplies etc) and another who handles people issues, ensuring that Jeremy’s instructions are carried out in-field.

Glen Rosa’s top men: Mzwokuthula Nzuza, Mkhalelwa Chiliza and Nkomo

Glen Rosa’s top men: Mzwokuthula Nzuza, Mkhalelwa Chiliza and Nkomo

People management is always a challenge and Jeremy has these tips in this area:

- Fluent Zulu is imperative in KZN. Cross cultural communication is challenging enough. Ensuring that the language barrier is removed goes a long way to team solidarity.

- Maxwell’s assistance has been key in diffusing many highly charged situations. Although it’s not something you can engineer, support from community members who can mediate disputes is invaluable.

- Simplicity. Misunderstandings are largely avoided when things are simple. Like wages: Jeremy pays one rate per tonne regardless of whether it’s one tonne, or twelve. He also doesn’t deduct any living expenses from the staff’s wages. Reimbursement is at the root of many problems; keeping it simple eliminates many of these.

- Grow for everyone. Maize is grown on the farm and mielie meal and amawhehu is supplied to the labour free of charge. Staff are also permitted to grow beans in some fallow fields.

- Step back. Jeremy allows his Indunas to do the hiring and firing; this way they own both the accountability and authority to manage effectively. It has worked well, especially in his timber team where a woman induna achieves 12 loads per month with just 5 strippers, 1 chainsaw operator and 4 loaders.

- Be amicable. Shouting, screaming and throwing weight around is the perfect recipe for a breakdown with labour.

The general growing cycle, out here in Dumisa, is 22-24 months and it’s no different on Glen Rosa. With such long growing cycles, the cane gets to an impressive size. Jeremy prefers not to use ripeners. He finds the schedule restrictive and prefers to work without the risk of going outside the ripener “window” period. This year, he will use ripeners on about 15 hectares that need to be brought back into cycle after a devastating fire annihilated the farm 3 1/2 years ago.

The general growing cycle, out here in Dumisa, is 22-24 months and it’s no different on Glen Rosa. With such long growing cycles, the cane gets to an impressive size. Jeremy prefers not to use ripeners. He finds the schedule restrictive and prefers to work without the risk of going outside the ripener “window” period. This year, he will use ripeners on about 15 hectares that need to be brought back into cycle after a devastating fire annihilated the farm 3 1/2 years ago.

Without artificial ripeners, the slight yellowing of a field is his indicator that a field is ready. Average RV’s are 12,5% but, in Sept / Oct it often gets up to 15 or 16%. If he could, he’d trash his fields but it is already hard enough to cut the lodged cane. A cool fire cleans it up just enough to allow access. In one carry over harvest, the cutters had to cut the cane sticks in half; Joe Nkala came to measure them – the 29-month-old N51 was 3,6 – 4,2m long. The result was 202 tonnes/hectare. Can you imagine green harvesting that! As it was, the tractors could not get access to the field because the stacks were so close. Bumper crop problems …

Here is Joe, holding up single sticks of sugarcane – it literally grew in circles.

Here is Joe, holding up single sticks of sugarcane – it literally grew in circles.

A few years ago, Jeremy changed from harvesting in windrows and in-field cane loaders to cut-and-stack. He feels the reduced compaction and ratoon damage has done wonders for his results and has extended ratoon life from 5 or 6 to well into the teens. The oldest ratoons were 17 – and these were only removed because the rows were no longer identifiable, grasses had also infested the field. The final crop from that field was harvested at 18 months and yielded 80 tonnes per hectare.

The cutters also prefer cut-and-stack because they can see their production and know that the stack is weighed and they are accurately remunerated. Remuneration on windrow harvesting was always viewed dubiously and a few cutters even left Glen Rosa, only to return when cut-and-stack was implemented.

This is a field of N12 on its 10th ratoon. Jeremy estimates the yield will be 90 – 95 t/h

This is a field of N12 on its 10th ratoon. Jeremy estimates the yield will be 90 – 95 t/h

The usual advice is to get the cane into the mill as soon as possible so that sucrose levels and weights are maximised. Jeremy has had a different experience and, if the weather is dry, he finds that leaving the cane on zone for 2 to 3 days after harvest actually increases the sucrose. The weight may drop but it negligible. So, in true laid-back Jeremy style, he does his best to get the cane into the mill within 48 hours but if it doesn’t happen, no biggie.

A vicious run away fire a few years ago taught Jeremy to burn his fields in a mosaic pattern so that there is always a fire-fighting platform available and risk is reduced.

Jeremy believes in a fallow period before replanting a field. He doesn’t follow the norm in terms of rotation crop choice though. Glen Rosa needs maize so that’s what the fallow fields are used for. The maize is used to feed everyone – livestock, staff and Jeremy’s family. And if you look at what’s left in a maize field after it has been harvested, you cannot argue that there isn’t plenty of organic matter (about 4 to 5 tonnes per hectare, which is substantially higher than most other rotation crops). A gyro-mower is used to chop the stova up and then it is disked into the field.

Jeremy believes in a fallow period before replanting a field. He doesn’t follow the norm in terms of rotation crop choice though. Glen Rosa needs maize so that’s what the fallow fields are used for. The maize is used to feed everyone – livestock, staff and Jeremy’s family. And if you look at what’s left in a maize field after it has been harvested, you cannot argue that there isn’t plenty of organic matter (about 4 to 5 tonnes per hectare, which is substantially higher than most other rotation crops). A gyro-mower is used to chop the stova up and then it is disked into the field.

If the maize planter cannot access a field (there are some pretty steep slopes here), then the community plants beans, which is a more common rotation crop amoungst the greater sugar community. Jeremy feels this is second prize for the soil as the harvestors take the whole plant out of the field, leaving almost nothing in terms of organic matter.

Generally, the 10% plough-out rule is followed with any field producing less than 95 tonnes per hectare being targeted. If he can get equipment into the field very soon after the harvest, he can cut out the need for Round Up because the root stock can be ploughed up, the field cross-ripped and disked. If resources are tied up elsewhere for too long then Round Up is sprayed to kill last crop.

Generally, the 10% plough-out rule is followed with any field producing less than 95 tonnes per hectare being targeted. If he can get equipment into the field very soon after the harvest, he can cut out the need for Round Up because the root stock can be ploughed up, the field cross-ripped and disked. If resources are tied up elsewhere for too long then Round Up is sprayed to kill last crop.

Rather than following set steps, Jeremy listens to his gut for all operations and planting is no different. He assesses the requirements of each field individually when prepping it for planting. Once the stova has been disked in, he ridges, only opening as much as can be planted in one day. He does this because soil lying open too long can form clods that won’t settle snugly around the new seedcane when furrows are closed.

Into the furrow he places fertiliser (2:3:4). Onto that goes the double sticks of cane, where they are chopped. On the more level fields, he then uses a closing tool which performs three tasks: it sprays Bandit, folds the soil into the furrow using two discs and presses it down lightly with a wheel. This tool saves about 10 units of labour in the planting process. Sorry – I would have taken a picture but someone’s borrowed the tool …

This high-cost centre has been carefully considered by Jeremy and his choice of products are worth noting. Jeremy believes that all living things evolve to survive the challenges in their environment. Weeds are no different. As most farmers use the cheapest products on offer (and thereby contribute to wide-spread resistance to those chemicals) he has chosen to use different chemicals, which happen to be slightly dearer. Currently in his arsenal is Merlin, Galago and Dinamic. Dinamic has definitely helped in fighting ageratum, which was becoming a problem on Glen Rosa. He hopes that, when the majority of farmers have to switch to a different (possibly much more expensive) chemical to overcome resistance, he will still be able to use the more affordable options.

This high-cost centre has been carefully considered by Jeremy and his choice of products are worth noting. Jeremy believes that all living things evolve to survive the challenges in their environment. Weeds are no different. As most farmers use the cheapest products on offer (and thereby contribute to wide-spread resistance to those chemicals) he has chosen to use different chemicals, which happen to be slightly dearer. Currently in his arsenal is Merlin, Galago and Dinamic. Dinamic has definitely helped in fighting ageratum, which was becoming a problem on Glen Rosa. He hopes that, when the majority of farmers have to switch to a different (possibly much more expensive) chemical to overcome resistance, he will still be able to use the more affordable options.

Hand weeding units have also been used extensively on Glen Rosa but this year, Jeremy will implement a programme of spot spraying and hopes to cut labour costs in this way. The plan is to apply pre-emergent herbicide after planting, before spiking, and then spot spray from there, hand weeding some broad leaves and grasses only if essential.

Much of what Jeremy does on Glen Rosa is shaped by a terrifying experience that happened three and a half years ago. The typically dry and windy conditions of August turns farmers across the province into hawks, constantly scanning the horizons in search of that dreaded smudge of smoke. On this day, a wicked westerly had just flared up and Jeremy’s heart sank when he spotted smoke over the neighbouring Sappi forests. He alerted the Sappi team and sped to his boundary by which time 30 hectares of their forest had already burnt. The gum plantation on Glen Rosa’s border had recently been felled and was full of fire fuel. All too soon, the wind was whipping burning logs – literally branches – into Jeremy’s fields. Jeremy couldn’t expect help from the Sappi firefighters as they were fully consumed in their own hell. But neighbours descended from far and wide. Together they tried to back burn but it was futile. The fire was airborne and simply leapt over the corridors they created. When a new fire started 1,6kms away from the main fire, Jeremy retreated to the houses and did what he could to back burn from there. Donna ran into the house, throwing gas bottles into the swimming pool and opening the gates of all animal pens. In the final few minutes she thought about what precious items she should grab from her home but survival was so threatened that knowing her children and animals were safe was all she needed. She ran out and left it all. The animals – horses, dogs, sheep, cattle – had all congregated in the valley, and lay down next to the dam. With God’s grace and more friends than Jeremy knew he had, the fire side-stepped the houses but left every last breath of air thick with suffocating smoke. Not a single animal died and only two people suffered injuries: an escaping buck knocked one of the farmers flying and another woman broke her ankle jumping off a bakkie. All things considered, the casualties were minor. About 130 hectares of cane (70% of the farm) was decimated. They harvested it all in the following three weeks but the fire had been so hot that most of the cane was ash. Even freshly germinating fields were burnt beyond.

Much of what Jeremy does on Glen Rosa is shaped by a terrifying experience that happened three and a half years ago. The typically dry and windy conditions of August turns farmers across the province into hawks, constantly scanning the horizons in search of that dreaded smudge of smoke. On this day, a wicked westerly had just flared up and Jeremy’s heart sank when he spotted smoke over the neighbouring Sappi forests. He alerted the Sappi team and sped to his boundary by which time 30 hectares of their forest had already burnt. The gum plantation on Glen Rosa’s border had recently been felled and was full of fire fuel. All too soon, the wind was whipping burning logs – literally branches – into Jeremy’s fields. Jeremy couldn’t expect help from the Sappi firefighters as they were fully consumed in their own hell. But neighbours descended from far and wide. Together they tried to back burn but it was futile. The fire was airborne and simply leapt over the corridors they created. When a new fire started 1,6kms away from the main fire, Jeremy retreated to the houses and did what he could to back burn from there. Donna ran into the house, throwing gas bottles into the swimming pool and opening the gates of all animal pens. In the final few minutes she thought about what precious items she should grab from her home but survival was so threatened that knowing her children and animals were safe was all she needed. She ran out and left it all. The animals – horses, dogs, sheep, cattle – had all congregated in the valley, and lay down next to the dam. With God’s grace and more friends than Jeremy knew he had, the fire side-stepped the houses but left every last breath of air thick with suffocating smoke. Not a single animal died and only two people suffered injuries: an escaping buck knocked one of the farmers flying and another woman broke her ankle jumping off a bakkie. All things considered, the casualties were minor. About 130 hectares of cane (70% of the farm) was decimated. They harvested it all in the following three weeks but the fire had been so hot that most of the cane was ash. Even freshly germinating fields were burnt beyond.

Even though there was no loss of life, life changed on Glen Rosa. On the down-side, 50 staff members were retrenched and everyone had to learn to cope with a lot less. Donna started a small baking business, hoping to bring the ‘ends’ a little closer …

Even though there was no loss of life, life changed on Glen Rosa. On the down-side, 50 staff members were retrenched and everyone had to learn to cope with a lot less. Donna started a small baking business, hoping to bring the ‘ends’ a little closer …

The following season was phenomenal when it came to yields – previously, plant crops typically delivered 120 – 125 tonnes per hectare but, since the fire, Jeremy hasn’t had a plant crop deliver anything under 143 tonnes per hectare. He cannot explain whether the fire somehow altered the soil or whether it was something else at play but sugar cane farming at Glen Rosa is a lot better since the ‘great fire’.

Donna’s bakery is thriving. Any of you visiting a Coastal Farmers branch will have been tempted by her rusks and biscuits, and Glen Rosa Home Baked Goodies can also be picked up at the South Coast Shell Ultra Cities. She spoiled me with a goodie bag and I can vouch for their deliciousness!

Tembi and Baso work in Glen Rosa Home Baked Goodies Bakery.

Tembi and Baso work in Glen Rosa Home Baked Goodies Bakery.

Sometimes great disasters clear the way for great successes. Although 29 August 2014 was one of their darkest days, the Coles are grateful for the changes that day brought.

For a period, Jeremy practiced field-specific sampling followed by customised fertiliser application. It was highly administrative and full of risks – inevitably someone was going to make a mistake somewhere! His more laissez-faire approach to life soon drew him back to working on gut-feel. Nowadays, he doesn’t sample the soils, and has a formula that he feels works well: after the cane spikes, he applies 6:1:8 (with all the additives) for the first 2 or 3 ratoons, switching to something like 4:0:5 after that. He doesn’t use 1:0:1 at all. He opts for coated, Urea-based products. After ‘the great fire’, Jeremy added chicken litter to many fields. At first ratoon, those fields never produced less than 152 tonnes per hectare, which was a significant increase over the previous plant crop average.

For a period, Jeremy practiced field-specific sampling followed by customised fertiliser application. It was highly administrative and full of risks – inevitably someone was going to make a mistake somewhere! His more laissez-faire approach to life soon drew him back to working on gut-feel. Nowadays, he doesn’t sample the soils, and has a formula that he feels works well: after the cane spikes, he applies 6:1:8 (with all the additives) for the first 2 or 3 ratoons, switching to something like 4:0:5 after that. He doesn’t use 1:0:1 at all. He opts for coated, Urea-based products. After ‘the great fire’, Jeremy added chicken litter to many fields. At first ratoon, those fields never produced less than 152 tonnes per hectare, which was a significant increase over the previous plant crop average.

Fertiliser applications are split 60:40 and are done by hand, using tins. Although this may seem a little ‘rustic’ Jeremy insists that it works. The staff are shown how many metres must be covered by one tin and off they go. No moans about chaffing applicator straps, just tins and sacks! Of course, the indunas need to keep an eye on consistency. The second application is put down 6 to 8 weeks after the first. Since splitting the application, he has definitely noticed improved plant health and growth.

Jeremy purchases his fertiliser early (July / August) and watches the weather. The day before the rain, he gets busy. This careful timing, and opting for coated fertilisers, means that volatilisation is not an issue.

Liming is not standard practice on Glen Rosa but Jeremy will apply around 2 tonnes per hectare if he feels aluminium toxicity is an issue in a field. He identifies this need by assessing stick length and thickness as well as weed presence (specifically grasses). His gut is telling him that more of the farm is ready for increased lime supplementation.

Beans have been planted in the fallow field opposite as it is too steep for the maize planter. Jeremy says that it is a good example of a field that is challenged by aluminium toxicity and will require liming.

Beans have been planted in the fallow field opposite as it is too steep for the maize planter. Jeremy says that it is a good example of a field that is challenged by aluminium toxicity and will require liming.

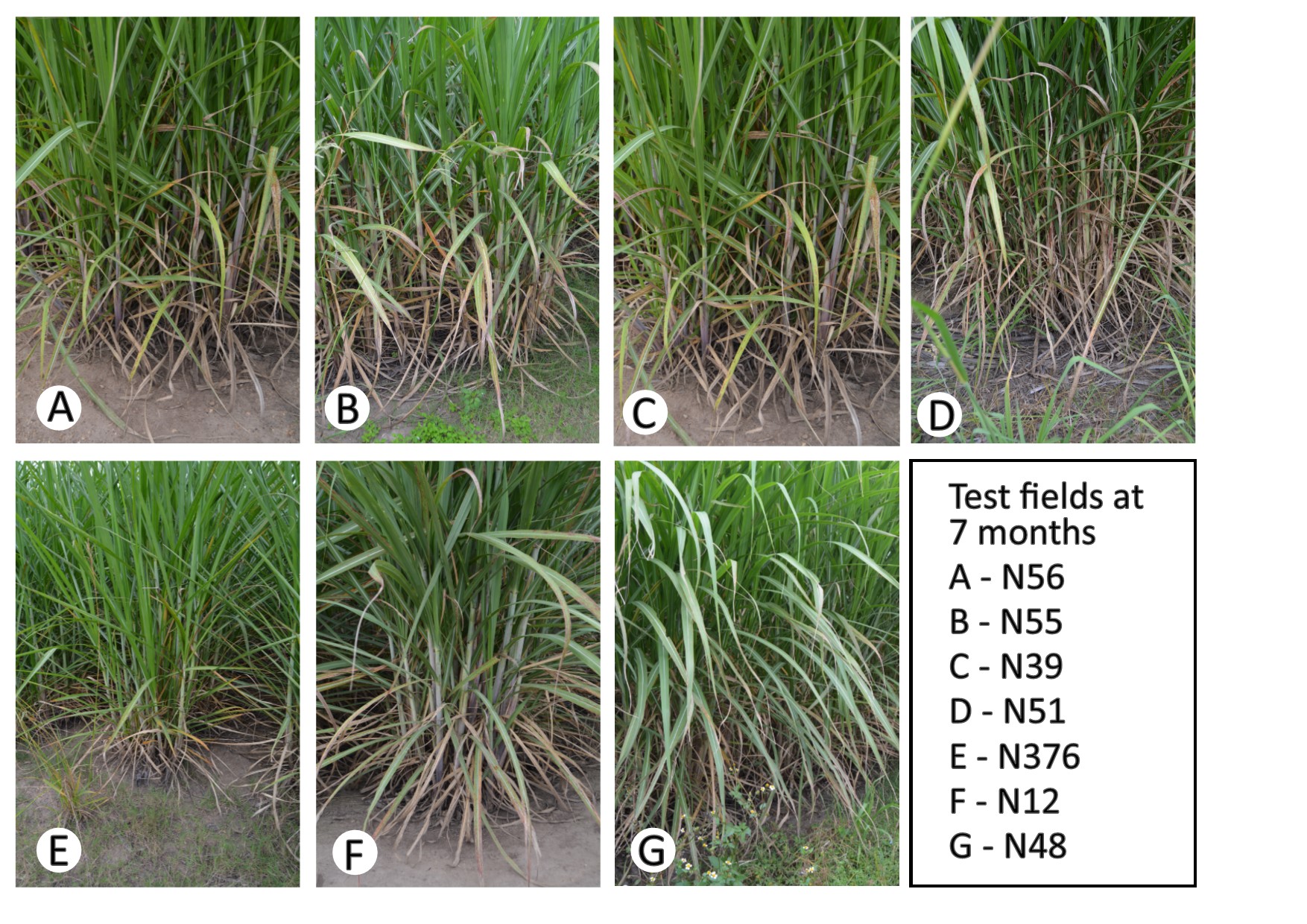

Jeremy produces his own seedcane which grows in a nursery or ‘test fields’, as he calls them. He is always excited to try new varieties but limits them to about ¼ hectare stands while they are proving themselves. He currently has about 7 varieties in there, all next to each other so their progress is easily compared.

Jeremy produces his own seedcane which grows in a nursery or ‘test fields’, as he calls them. He is always excited to try new varieties but limits them to about ¼ hectare stands while they are proving themselves. He currently has about 7 varieties in there, all next to each other so their progress is easily compared.

His current favourite is N12, as a staple variety, as it gives good sucrose. On the down-side, it does struggle through winter. N51, on the other hand, seems to sail through winter. N52 and N48 are also showing a lot of promise. They still need to prove themselves in the fields though.

N39 has proven to fail after the 5th ratoon and is therefore being ploughed out of Glen Rosa. When this variety was in the test field, Jeremy noticed a hiccup between its first and second ratoon but needed the space and planted it out to three fields. Lesson learnt.

N58 is currently doing really well, and Jeremy proudly claims that he still has two fields of 376 – an inside joke with a couple of fellow farmers.

N51 also revealed its unique growing pattern whilst in the Glen Rosa nursery: it was the first cane Jeremy used his closing tool on and, when the cane hadn’t spiked like it should, he blamed the tool, thinking it’d killed the cane. But, this slow start turned out to be a trait of the N51, which is now one of Jeremy’s favourite varieties as it always finishes strong.

Besides Bandit in the furrow, no pesticides are used. Sporadic Eldana infestations never develop to anything higher than 3 or 4 in a drier area and one year, when Jeremy did spray them, it turned out to be the worst decision. Granted, he never did the second application, but the field was pretty much ruined by the Eldana, after one spray.

Besides Bandit in the furrow, no pesticides are used. Sporadic Eldana infestations never develop to anything higher than 3 or 4 in a drier area and one year, when Jeremy did spray them, it turned out to be the worst decision. Granted, he never did the second application, but the field was pretty much ruined by the Eldana, after one spray.

Jeremy chooses to lead a life balanced well between work and play. Being able to wake up every day and be excited about what he does, be it work or play, is vital. In order to sustain this financially, he must always consider the most lucrative crops. Enter macadamias: Glen Rosa now has 29 hectares and the plan is to double that over the next couple of years.

Jeremy chooses to lead a life balanced well between work and play. Being able to wake up every day and be excited about what he does, be it work or play, is vital. In order to sustain this financially, he must always consider the most lucrative crops. Enter macadamias: Glen Rosa now has 29 hectares and the plan is to double that over the next couple of years.

On the right is a new orchard of Macadamias. Below that is a fallow field with mielies. Macs have been planted in there as well – the maize has served as a windbreak and the stova will be used as mulch.

On the right is a new orchard of Macadamias. Below that is a fallow field with mielies. Macs have been planted in there as well – the maize has served as a windbreak and the stova will be used as mulch.

160 hectares of gum plantations also contribute to the operation. The 40 or so head of Nguni cattle will eventually become an income source but , for now, they’re just ‘nice to have’.

And then, Donna’s bakery is an income (and yummy) stream that I am sure Jeremy encourages. Donna is also considering completing her psychology degree now that the children are getting older. I am always so proud of how versatile, energetic and ingenious our farming community is, despite the constant threats to their existence and lifestyles.

And whilst on the topic of challenges … what plagues Glen Rosa? Poaching is the most rampant crime at the moment, although theft has visited a few times … one spectacular event happened about 5 years ago, early in the morning whilst everyone was gathering to start the day. Donna had eventually loaded reluctant kids into the car and was about to begin the school run when gunshots and screaming sent her into defense-mode. At the sight of guns, all 86 staff members vapourised (through the electric fences) and Jeremy was alone, retreating towards the house, shouting at Donna to get inside. Donna didn’t hear the instruction and thought Jeremy had been shot so she ran along the fence-line, shooting as she went. The robbers took off but not before she turned their rear window into glitter. Only when Jeremy touched her arm did she realise that he was alive and it was all over. From this expereience, the Coles share the following advice: Arm yourselves and remain aware always. Don’t be submissive. Shout, scream and defend yourself for all you are worth. Be wary of any censuses, especially ones that require access to the property and want to know where the old folk live – yes, believe it or not, criminals will try anything.

Although this farm does run on minimal equipment, Jeremy is specific about what he does buy. He’s a John Deere man, having come from a long line of John Deere men. He believes they are quicker on turn around to the zone and is happy to see that the prices have become a lot more reasonable lately. He warns against buying electronic tractors though, John Deere or not. He made that mistake and can confidently confirm that basic tractors are the only way to go, especially if you intend allowing others to drive it, or take it anywhere near dust!

Although this farm does run on minimal equipment, Jeremy is specific about what he does buy. He’s a John Deere man, having come from a long line of John Deere men. He believes they are quicker on turn around to the zone and is happy to see that the prices have become a lot more reasonable lately. He warns against buying electronic tractors though, John Deere or not. He made that mistake and can confidently confirm that basic tractors are the only way to go, especially if you intend allowing others to drive it, or take it anywhere near dust!

Jeremy’s latest acquisition

Jeremy’s latest acquisition

Glen Rosa also treasures its old Ford crane, from the 60’s and a Bell loader which is almost 30 years old and still going strong.

Here are a couple focus areas that Jeremy feels are major contributors to the great figures he manages to produce:

Here are a couple focus areas that Jeremy feels are major contributors to the great figures he manages to produce:

- It is imperative to fallow your fields before replanting. Less important is what you plant during that fallow period, but make sure you have a good reason for whatever it is.

- Watch costs. As in most homes and businesses, there’s always the spender and the saver. It’s no different at Glen Rosa. Regardless of who fills which role, it is important that all spending is carefully considered.

- Trust your gut. Listen to the advice of others but allow your gut a say too. No one knows your land like you do. Learn to trust that instinct and be bold.

- Being the most laid back of all the Coles out there, Jeremy emphasises the importance of balancing life between play and work, which can be a challenge when you live on/in your business.