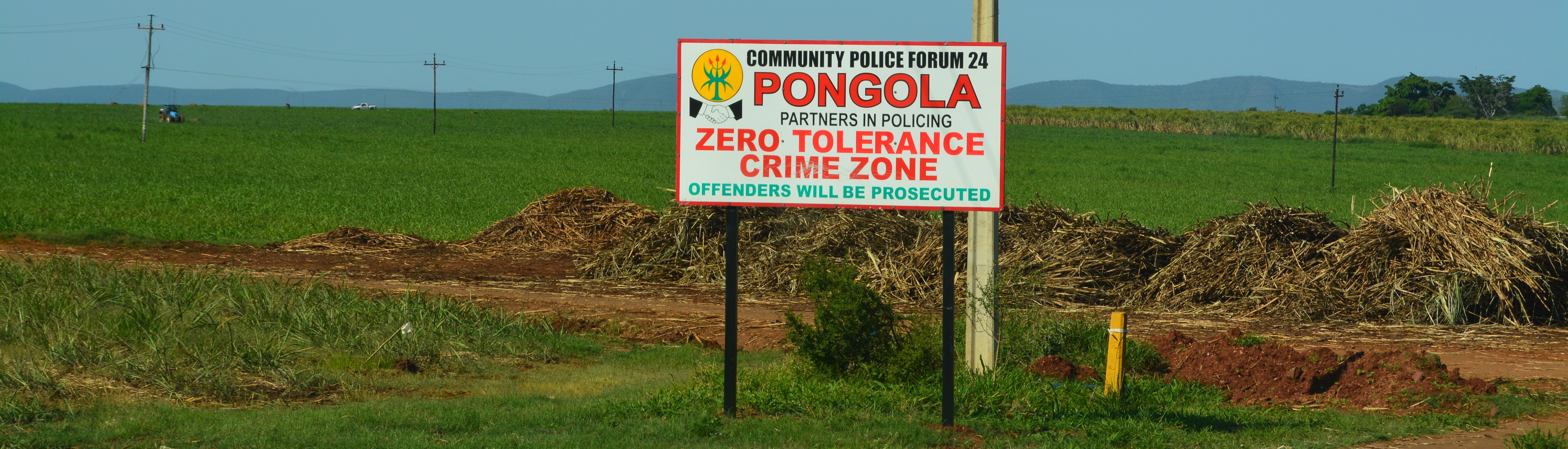

So, here I am, back in Pongola. It is such a stunning part of our country, although the town still scares me a little after my harrowing experience when I first visited in 2016. I was a little embarrassed, but hugely impressed, when I learnt that much has been done on the security front as a result of that incident. Well, not that incident alone, but apparently it was a strong motivator to beef up security. Since then, these signs have gone up and crime prevention forums monitor the situation constantly.

I was grateful for the initiative and definitely felt safer during this visit. Well done Pongola!

But, even if this is a typical South African town, with the usual inherent dangers, no one can deny the diverse beauty of the surrounding countryside:

Thank you, Pongola, for a wonderful visit. It was an event free journey both here and back, although the volume of loaded cane trucks leaving Pongola, as I was arriving, baffled me.

Pongola Mill has diverted cane to Felixton and Umfolozi as its crushing capacity has been exceeded.

Pongola Mill has diverted cane to Felixton and Umfolozi as its crushing capacity has been exceeded.

I am grateful to everyone who welcomed me in warmly, gave me many, many hours of their time and years of their experiences and wisdom (and English). On behalf of everyone reading this article on the SugarBytes website, we thank you whole-heartedly.

The first of our awesome farmers are the Meintjies men: Delarey and his son, Albie.

| Farmer | Delarey and Albie Meintjies | ||

| Date interviewed | 9 October 2018 | ||

| Date newsletter posted | 22 October 2018 | ||

| Farm | Robyn Trust | ||

| Area under cane | 160 hectares | ||

| Annual tonnes | 17 000 tonnes annually | ||

| Mill | Pongola | ||

| Distance from mill | 10kms | ||

| Cutting cycle | 12 – 14 months | ||

| Av Yield | 122 tonnes | Best Yield | 200+ @ 14 months |

| Av RV | 12.5% | Best RV | 14% |

| Gradients | Mostly flat | ||

| Varieties | N36, N41, N46, N57, N53 | ||

Although I glimpse the hooligan cowboy in Delarey, he manages to tame the renegade during our interview and is a consummate professional. The success of his operation is proof that he is more responsible and knowledgeable than he tells me he is and hearing about his ups and downs to this point in his life is fascinating.

BACKGROUND

Not sure about you but when I heard Delarey’s name I knew it was related to a song somehow. Only when I searched for it did I discover that it was slightly controversial, but we can (and often do) make mountains out of mole hills when it comes to our cultural differences. If any of you are curious about the song, click on this picture.

The era portrayed in this music video is representative of Delarey’s roots – his family has always been in farming. His Grandfather owned a farm in the Free State named Galaxy. At the time, his grandfather’s sister, a lady named Engela, was engaged to General CR de Wet’s son. This man was shot and killed by an English sniper. Delarey has a photograph (too deeply filed for me to get a copy, sorry) of his great aunt and General CR de Wet, along with three others, leaving Galaxy to round up support for a reciprocal attack – the start of the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Now that’s a rich history!

In 1960 Delarey’s Dad started farming in Mtubatuba. He was one of the founding members of the original Umfolozi co-op. After about 20 years there, many of the surrounding farms were bought out by timber companies and Mr Meintjies decided to move on aswell. He bought a sugar farm in Pongola in 1980. At this time, Delarey was doing a millwright apprenticeship but paused that to assist his Dad in running the farm. When his own small family started to grow he moved off the farm and completed his apprenticeship. His journey took him to Newcastle and then to the mill in Pongola. But that deep, irresistible passion that many have for farming eventually pulled him back and he once again joined his Dad. He worked incredibly hard and brought the farm’s production up from 7000 tonnes to 12 000 tonnes.

Together, Delarey and his Dad bought, improved and sold a series of farms, building up capital and portfolio along the way. When the time was right, his Dad said he could buy half the land. The other half was offered to Brandt, Delarey’s younger brother. In the meantime, Delarey had started to build up a plant hire business on the side. He kept the machines busy clearing lines for Eskom and scooping out dams for local farmers. This business provided the finances he needed to buy the farms from his Dad.

Since then, his portfolio of farms has changed; he sold the original ones and bought others that better suited his requirements for flat lands with excellent soils. He believes he now has one of the best farms in Pongola. It is mostly below the river and is on an eastern slope with deep, stone-free soils. To satisfy his wife’s need for security, he lives in town rather than on the farm.

FARMING ADVICE

Delarey is joined by his youngest son, Albie, who, at just 27 years of age, is still learning from his Dad but he already has firm ideas and a strong passion for farming that will ably grow the Meintjies legacy in agricultural excellence. These two men think they are anything but remarkable though and, throughout the interview, they constantly refer me to other farmers in the area whom they admire. Delarey says, “I farm for Show, not for Dough.” He loves the farm to look good – neat and tidy roads, with happy, healthy plants and somehow thinks this makes him less successful but, when I hear about his average yields (currently on 122 tonnes/hectare but looking likely to close at around 125 tonnes/hectare this season) I am not convinced about his assessment of himself.

The estimate for this field is 130 tonnes/hectare. There wasn’t meant to be cane in this little area because it floods periodically but they’ve had 2 successful years from it so far and will continue for now.

The estimate for this field is 130 tonnes/hectare. There wasn’t meant to be cane in this little area because it floods periodically but they’ve had 2 successful years from it so far and will continue for now.

So, how does this team do it?

REPLANTING AND LAND PREP

Although they try to keep replanting to around 10% of the land, these are not strict farmers. Any field producing less than 110 t/h is earmarked for replanting though. (I can see our southern-KZN farmers groaning at that … remember guys – they irrigate here )

After harvesting for the last time, they clean the fields completely, using up to 3 applications of Round Up.

As break crops are common currently, I expected the same here but Delarey doesn’t practice this, for 3 reasons:

- He has had bad experiences with vegetables.

- Trade-off. He believes that the improvement to his crop from the improved soil health that a break crop might contribute will be of less value than the 5 – 12 months growth he will gain by going straight into another sugar crop.

- His soils are so healthy that he doesn’t see the need for this practice currently but, if they decline, he will consider it.

The bad veggie experience might have value for other farmers considering alternate crops so here’s the story behind that: Tomatoes were a great source of supplementary income and Delarey had planted them across many of his farms. He was supplying the Hawkers trade but decided to expand substantially. By sending the crop to market he encountered two challenges: ZZ2 and truck drivers. Although he was supplying 15 tonnes per day, 5 days a week, it wasn’t enough to compete with the market giants: ZZ2. And his “entrepreneurial” truck drivers started running their own delivery service on the way back from town and then stole whatever diesel they hadn’t used.

Then came the final straw: aerial cane ripening on a neighbouring farm blew over 20 hectares of his tomato crop. The results were varied – young plants died straight away, the bearing plants produced mis-shaped fruit and the developed plants all ripened at once meaning he had to pick and deliver 40 tonnes per day to avoid losing them. Understandably, it was enough to quell his interest in tomatoes.

When Albie started farming with Delarey, his first project was a field of cabbages. Delarey laughs when he says, “I should have just given him the cash instead of the seedlings and told him to throw it away.” Albie defends himself, saying, “I learnt two important lessons: one was that I should do better research on the variety of plant I want to grow (the one he chose was too small) and the other is to research the market better.” Albie went on to explain that there are a few highly successful cabbage farmers in the area and they stagger their supply to the hawkers so that they don’t compete with each other. He wasn’t aware of this arrangement and therefore couldn’t find a market to buy his produce. Transporting his stock to the official market was not financially viable. All valuable lessons, from which the Meintjies men concluded that they don’t like vegetables!

Back to Land Prep: after making sure that the Round Up has cleared the field completely, the field is worked until it is fine and flat. Delarey concedes that he might work the soil a little too much but it is what he likes to do (part of the farming for Show …) and he believes that there is value in minimising the amount of air around the cane billets when they’re planted. Into this fine seed bed, furrows, 1,5m apart, are cut. This suits all their equipment and ensures that cane stools are not damaged by in-field traffic.

1,5m row spacings:

Because the Meintjies’ farm intensely, and they have a nice warm, eastern facing aspect, they can start planting as early as August. They select their seed cane very carefully, preferring vigorously growing plants that are not too young nor too old. Certification is mandatory. Delarey emphasises that sourcing the very best seed is vitally important to one’s success. In terms of varieties, both he and Albie are enjoying the yields of the new N53 and N57, they just wish they could get better RV’s from them at the same time.

Double sticks are placed in the furrows, cut into sets and sprayed with fungicide through knapsacks.

Fertiliser is applied into the furrow which is then closed. The field is given a really good, deep soak of water and left to germinate.

This field had just been planted 10 days ago. Only received one dose of fertiliser so far – the MAP which was put in the furrow with the sets.

This field had just been planted 10 days ago. Only received one dose of fertiliser so far – the MAP which was put in the furrow with the sets.

Here is Albie standing alongside a field of N41

Here is Albie standing alongside a field of N41

Very sandy in this field too but the N57 variety is doing well – only 7/8 months old. This is Albie’s favourite variety at the moment.

Very sandy in this field too but the N57 variety is doing well – only 7/8 months old. This is Albie’s favourite variety at the moment.

FERTILISERS

What I loved most about Delarey and Albie was their honesty and I am going to share that because it’s real and relevant to so many of us. When I asked about soil samples, they admit that they do them sometimes. The challenge is that the results take about 6 weeks to come back and, when you only think about the need for them at replanting, no one wants to wait 6 weeks to get going. So, they send the sample in and carry on. When the results come back and (usually) they call for lime and gypsum, the men chat about it briefly and move on.

Money also has a lot to do with not following recommendations fully: supplements are often very expensive. Further south in KZN, our farmers are spoilt by having the lime mines fairly close but here, the nearest mine is about 500kms away so, while the product itself is affordable, the transport isn’t.

When cash flow is better (which isn’t the case currently with the poor sugar price) they have tried various supplements. Their experience with kraal manure is interesting; two years ago, they bought in volumes of the product but didn’t have a suitable applicator. Doing the best they could they shovelled it off the back of a flatbed trailer and spread it into the field with a grader. The result was uneven deposits of raw manure and the high nitrogen content burnt the young cane plants. Despite that initial set back, those fields are now thriving. So much so that they would definitely recommend adding kraal manure to your plant fields – just use a proper applicator and an aged product (2 years seems like a good time period).

Standard practice here is to apply 400kgs / hectare of MAP (plus Zinc) on plant cane. MAP is new to me and it might be an unknown for others so here is a little detail: MAP has been an important granular fertilizer for many years. It’s water-soluble and dissolves rapidly in adequately moist soil. Upon dissolution, the two basic components of the fertilizer separate again to release ammonium (NH4+) and phosphate (H2PO4–). The pH of the solution surrounding the granule is moderately acidic, making MAP an especially desirable fertilizer in neutral- and high-pH soils. So, the MAP is the fertiliser they put in the furrows with the plant cane. About 3 weeks after planting they use the ripper applicator (to get the product INTO the soil, limiting volatilisation) and put down Urea (Nitrogen) and KCl (Potassium Chloride). In this way the soil receives all the required NPK, just in slightly different forms. Delarey chooses to buy the products separately like this as it is more cost efficient than purchasing the mixed fertiliser. His choice of application is also very deliberate and designed to provide the supplements the cane requires exactly where and when they are best utilised by the plant.

Ratoon cane. 10 days growth. Inter-rows ripped and KCl applied:

Ratoon cane. 10 days growth. Inter-rows ripped and KCl applied:

When it comes to ratoon cane they apply 200kgs of Urea and 150kgs of KCl per hectare. This is done in two applications. The soils are ripped about every 5 years to help alleviate compaction. When this is done, the fertilisers are applied during ripping.

PESTICIDES

Luckily there are no pest threats on this farm, well, nothing that requires spraying. The only chemicals used for a ‘pest’ are fungicides in the planting process. With plant cane this is applied by knapsack sprayers and when they are gapping a field early in the season they’ll actually dip the cane billets into a tank containing the same chemicals.

Here is patch of cane that has been left to use as seed cane to fill the gaps in this field.

Here is patch of cane that has been left to use as seed cane to fill the gaps in this field.

WEED CONTROL

After harvest, weeders are deployed to hand hoe grass stools. Two months after cane has grown out, they’ll do another hand weed. Besides this, herbicides are used immediately after the fertiliser top dressing. They use Alligator for the grasses and Tarantula for the broad leaf weeds. MSMA is used on particularly troublesome fields but they are careful with the use of this product as it tends to be quite harsh.

IRRIGATION

I was fascinated to learn about the water regulation system in Pongola. It is managed by Impala Water Users Association. The Pongola River is a decent sized river but it fell short of satisfying the town’s agricultural, industrial and domestic needs. To stabilise the water supply, sugar farmers, the Pongola mill and local government partnered with Impala in 2000 to build the Bivane Dam near Vryheid, about 100kms away from Pongola. Farmers now order water from Impala a few days before they need it (it takes 2 days to travel from the dam to the irrigation canals) and the supply is steady. Delarey and Albie watch the weather reports closely and adjust their orders accordingly; with the recent good rains, they have not ordered water for almost 4 weeks now.

Bivane Dam has a catchment area of 1600 square kilometres, and a surface area of 700 hectares.

Experience has taught Delarey to resist the temptation to over-water. The goal is consistency – try to keep the soil’s moisture content constant without over or under irrigating. This is not always possible and you have to compromise in some areas, like one field they have which is on a slope. Because the water applied on the top filtered to the bottom, the lower part was becoming too wet. The solution was to find a compromise that leaves the top half slightly dry so that the bottom half didn’t drown. Delarey explains that it is better to slightly under-irrigate than to over-irrigate. Plant’s roots were not designed to swim – they cannot absorb the nutrition they need to support the growth we require. The chances of a healthy plant are better with less water.

In Pongola, irrigation happens across the board and as is somewhat of a master-art. There are so many anomalies that go into the practice making it very scientific. Systems, equipment, soils, varieties, timing, direct and indirect costs, gradients, flexibility, linked tasks (like fertigation) all play a role in deciding what will deliver the best results. It’s a fascinating part of farming in the north and one Delarey and Albie enjoy fine tuning. They started reconfiguring their farm and all the irrigation a few years ago and, now that it is almost complete, they feel that the farm can really start to perform consistently.

They have chosen centre pivots, semi-permanent sprinklers and some flood irrigation. Flood irrigation is a firm favourite because the set up costs are so minimal but the gradient of the land has to be perfect. Delarey chose to use it in this field which is close to town (so theft of equipment is outrageously high) and it has the perfect gradient.

This water will make it half way across the field (80m) and then there is another mainline pipe in the middle to do the bottom part.

This water will make it half way across the field (80m) and then there is another mainline pipe in the middle to do the bottom part.

Second favourite is the centre pivot. The advantage of this system is its flexibility as the pivot can be set to irrigate parts of the circle if necessary, without any labour requirement. It also has extensive reach so up to 12 hectares can be irrigated in 24 hours.

There are a couple of challenges with centre pivots but they are usually easily addressed:

- The wheels can create ruts in soft soils. This has been addressed by collecting building rubble and creating a path for the pivot.

Stock piled rubble Centre pivot pathway.

Stock piled rubble Centre pivot pathway.

- The motors are often removed by neighbouring wealth redistribution agents. Delarey designed and commissioned a steel case (pictured below) that has proved to be a successful deterent.

- Dry ‘corners’ are left around the centre pivots. Semi-permanent sprinklers cover these spots.

Recently, on one part of this farm, the cane under centre pivot got so big that it toppled the rig. A nice problem to have when you’re thinking about yield but it did cost just under R30 000 to upright. This passage was cut to free up the equipment:

I was interested to hear Delarey’s view on drip irrigation – he’s not a fan. With his farm being so close to human settlements, he has many uninvited four-legged skinny dippers in his dams (local cattle). Their escapades stir up the silt and block up the drippers faster than he can filter the water and clean the system. It just doesn’t work. The things we have to take into account when selecting a system!!

MECHANISATION

When Delarey sold some of his original farms he finally had money to do what he’s always wanted to do: buy new equipment to replace their old fleet. He was so tired of constant breakdowns and repairs, never mind the endless bills. So, over the following 3 to 4 years they upgraded the whole fleet, implements included, to newer models. “This is the way to go,” he advises, “what you spend on the new stuff is no more than you were spending on repairs with the old.”

I hear many opinions on the use of closing tools in planting and Delarey has some interesting advice: “If you don’t have time, then the tool is useful but, under ideal circumstances, closing by hand is first choice, especially if you’re planting early in the season and germination is risky. When time constraints have forced me to use a closing tool I often have to go back and redo a few areas by hand. Those patches always germinate better and can be as much as 2 weeks ahead of the tool-closed areas. Weather plays a large role too – when there’s a lot of rain, the difference will be less extreme.”

HARVESTING

In preparation for the harvest, Albie and Delarey ripen everything when aerial sprayers are available, and the cane hasn’t flowered.

This field of N23 won’t be sprayed with ripener as the purity will already be maximised by the flowering.

This field of N23 won’t be sprayed with ripener as the purity will already be maximised by the flowering.

N36 – this field will be the last one into the mill this year. Ripener: Ethapon and Fusilade piggybacked.

N36 – this field will be the last one into the mill this year. Ripener: Ethapon and Fusilade piggybacked.

Burning is standard practice across most of Pongola but not everyone burns both before and after harvesting, like Delarey. He burns the tops after harvest to make sure that all the soil is fully exposed to the herbicides, enhancing their efficacy. They also choose to do daily burns and thereby reduce burn-to-mill delays. The intention is to get everything into the mill within 48 hours of burning.

This field was cut about 4 days ago and the new cane has already pushed through. It hasn’t had any fertiliser or herbicide yet. The ash from burnt cane tops is still evident. They recently bought this farm, a year ago. The previous owner got 800 tonnes from it. Delarey and Albie have already cut 1500 tonnes and still have another 600 tonnes to go. They’ve successfully turned it around in one year!! They’ve achieved this by replanting, fertilising, irrigating properly and using fallow areas.

This field was cut about 4 days ago and the new cane has already pushed through. It hasn’t had any fertiliser or herbicide yet. The ash from burnt cane tops is still evident. They recently bought this farm, a year ago. The previous owner got 800 tonnes from it. Delarey and Albie have already cut 1500 tonnes and still have another 600 tonnes to go. They’ve successfully turned it around in one year!! They’ve achieved this by replanting, fertilising, irrigating properly and using fallow areas.

When I raised the topic of green cane harvesting, Delarey explained that he has tried it but trash worm infestations made it impossible to continue.

Albie and Delarey allocate one cutter per 1000 tonnes of cane. As their production here is 17 000 tonnes, they employ 17 cutters who are paid per metre with their production being measured every second day. Standard windrow placement with infield Bell loaders are used. If conditions are sufficiently dry then the transport trucks will come into the field but if there is any moisture in the soil then they prefer to load onto smaller trailers and transfer into the truck-trailers on the zone. Delarey believes they are doing the best they can with regards to minimising soil compaction by replanting regularly, ripping periodically and being cautious about infield traffic.

Currently they are replanting every 7 to 8 years. When yields average 130 t/h, they’ll slow down on replanting.

This field just produced 147 tonnes/hectare.

This field just produced 147 tonnes/hectare.

ADMINISTRATION

Not surprisingly, Delarey just shakes his head when I ask about administration. Not a strong point. Although Albie seems to be far more interested in refining this side of the operation. Now that the reconfiguration of the farm is almost complete, they can resume with accurate field records and use the information to manage practices and improve performance.

A trusted accountant is blessed with a shoebox of paper whenever it’s full and he rumbles the numbers, keeping the operation sound on the admin side.

LABOUR

The Department of Labour has been very active in this region recently. They have been conducting random inspections and handing out warnings and making arrests; most of the contraventions happen with minimum wage levels and employment of foreign nationals (many Swazis offer their cutting skills in this area). Thankfully, Albie and Delarey have managed to stay out of jail thus far but they do have to ensure they pass future inspections 100%.

Albie is definitely the “people person” in this team and he believes that you cannot just drop the workers off and expect the tasks to be done. He stands by them and checks what is happening. He’s also found that the staff productivity is improved by letting them know what tomorrow’s task are today. That way, they arrive and get on with their jobs immediately.

Both Albie and Delarey enjoy walking through their lands and agree that these walks are good for the whole operation … footprints are the best fertiliser …

What else makes this operation so successful? Delarey insists that he has just been lucky; he has been able to buy well-positioned (warm), adjoining farms with good soils and gentle gradients on the right side of the water source. Sounds smart rather than lucky to me but we’ll enjoy the modesty of this great farmer.

And all too soon my time with these wonderfully warm, honest and open men comes to an end. It’s been delightful to witness the handing over of the baton to the next generation and I am confident that Albie is going to continue in this rich heritage of farming excellence. And I look forward to hearing about Delarey enjoying more time with the love of his life …