| Farmer | Grant Taylor |

| Date interviewed | 27 July 2018 |

| Date newsletter posted | 10 September 2018 |

| Farm | Lomati |

| Farm size | 346 hectares |

| Area | Nkomazi |

| Mill | Komati |

| Distance from mill | 20 kms |

| Area under cane | 200 hectares under crop, 132 of that is cane |

| Other crops | Citrus, Banana, Mango, Litchi, Papino, Veg, Tomato, Peppers, Beans |

| Cutting cycle | 12.5 months |

| Av Yield | 125 tonnes per hectare |

| Av RV | 14 % |

| Varieties | N57, N53, N36, N25, N46, N19 |

I’m guessing that there are few in the industry who haven’t met or at least heard of Grant Taylor. He’s a big character – the kind of person who invests passionately wherever he finds himself. I first met Grant when I was working on getting the Komati farmers involved in SugarBytes. Being the Chairman of that Growers Association, I knew he was the man to talk to. But, all the way up there? Grant made my life a whole lot easier when he agreed to meet whilst in Durban and, since he learnt what we were all about, he has been a source of encouragement and inspiration, even going so far as to allow me to visit his farm and find out more about what’s behind this great farmer.

Grant is unapologetically independent. He expects help from no one but appreciates everyone around him. He disagrees with industry protection, politics and regulation. He’s a man who believes that you deliver your best when you are in a tight situation and, if your best isn’t good enough and you are squeezed out of that situation – so be it! He is a realist who has the ability to accept the facts and deal with them. Yes, the world around us is not always to our ideal but manipulation and denial is not the route Grant takes. He has chosen to embrace the reality of his position and do the very best he can with it. If others chose to learn from his journey, he is more than willing to share and, for that, SugarBytes is extremely grateful.

Grant prepared for my interview with him; upon arrival he gave me 3 pages of typed notes covering everything he felt would contribute to the article. I felt underprepared by comparison but it clearly outlined what kind of a man I was dealing with; what I was about to learn on Lomati was not ‘shooting from the hip’, it was well thought out and researched. Seeing intelligence, perspective and preparation join forces, I scrambled in a feeble attempt to keep up.

Let’s start at the beginning: Grant’s roots … he grew up in Swaziland, on a sugar and cattle farm. This farm was sold whilst Grant was still a child – a devastating moment for this ‘born’ farmer. He spent many years finding a way back into farming. This included qualifying as a construction plant mechanic and studying agriculture abroad, at The Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester; incidentally, the same college Jan Lourens studied at, and both insist it was the best possible education they could have had … now if only the Rand weren’t so weak against that Pound …

Anyway, after studying, Grant worked for a lawyer in the area who handled farm sales. He was a speculator who bought, developed and sold properties. Brett Hullett approached Grant as an investor with regards to a cane farm that interested him but was in huge trouble. Grant did the due diligence but the banks were reluctant to finance the deal. Ultimately one brave, insightful institution agreed to be the financier provided Grant agreed to be the farmer. Grant was cautious; the yields were too low and the soils too poor. Grant even has a SASRI report that states that the farm is unsuitable for irrigation and cropping. This was his ticket back into farming but it certainly wasn’t a business class seat. Grant took it anyway. The early years weren’t even economy class; he had his share of pap-dinners navigating the tough times but, 20 years later, he’s a partner in a bond-free, highly successful, operation that turns over R20 million annually. No regrets!!

SugarBytes celebrates! We have a farmer who has beaten circumstances, soils and odds. Time to learn how …

After chatting to Grant all morning I think his success is attributable to three key characteristics:

- He has the rare ability to clear the clutter from a scenario, to see it without the ‘noise’ most of us struggle to shut out. He is not a follower. He is a unique individual who has the courage and foresight to go where others are scared/nervous/intimidated/fearful to tread. He is an independent thinker, completely devoid of herd-mentality. You’re either born that way, or you’re not – most farmers are, and Grant definitely was. This characteristic facilitates independent clarity through which he can assess and navigate situations.

- He acknowledges that he is but only a single wheel in the machine required to power the farm. He knows he could never do it alone and so he selects and educates all the other ‘wheels’ in his machine carefully and equips them adequately to work towards the common goals.

- He has walked the best path to this point, picking up technical (mechanic qualification), financial (time with the prospecting lawyer) and farming knowledge (childhood on a farm & RAC education) that have combined to give him both the strategic insight and the practical ability to become the success he is.

Although we can certainly learn from these three factors, here is some more detailed information on a more practical level:

STAFF

Lomati has a permanent staff compliment of 60, inc security. During summer, when mangoes and litchis are harvested, this will go up to around 250 people.

Education: Solomon is Grant’s right hand man. He was on the farm when Grant moved in. Initially, the relationship was rocky, in fact it was so bad that Grant thought there might be bloodshed. It didn’t help that Grant demoted him almost immediately. Although Solomon earned the same wage, Grant put him back to the lowest rank of each department, mentoring him through a learnership in which he not only DID every menial task on the farm but UNDERSTOOD the value and purpose behind that task. He didn’t move on until he’d mastered it. It took about three years but today, Grant says that Solly runs one of the tightest ships in the SA cane industry and is a firm friend. I witnessed the mutual respect and loyalty between these two passionate farmers and it was a blessing available to others who are willing to risk temporary popularity and peace for the bigger reward of a sustainable partnership.

Today, with Grant’s support, Solly puts all employees through the same learnership programme he grew from. Tractor drivers start with the basics in mechanics and also learn to weld. The programme for all employees includes detail on fertiliser and herbicide applications, coefficient of uniformity in the context of irrigation, herbicides and fertilisers. They study the various types of irrigation; quantity and sizes of nozzles, arrangement of sprinklers, working pressure and the speed and direction of the wind. Pest and disease scouting, weeding standards, man-day analyses and tasking are some of the other areas covered.

There are no irrigation, fertiliser or herbicide specialists, neither is anyone limited to mangoes, bananas or sugarcane. Everyone is fully capable and equipped to work wherever they’re needed. In the mornings, after roll-call, Solly gives each labourer a ticket and they stand one side. Each Induna is allocated a task with a set number of man-days in which to achieve it. He then selects his labourers and heads off to get the job done. Solly has a “bank account” that starts the year with a balance of 19500 man-days in it. If he overspends, he finds himself applying for overdraft facilities with a man not prone to granting that easily. But if he comes in below budget, he is handsomely rewarded.

Selection: Grant and Solly only hire people who are passionate about farming. Employing people who have this simple aspiration has made all the difference in maintaining a happy, committed and invested workforce. Grant also pays above minimum wage which goes a long way to attracting ‘above minimum’ applicants.

Measurement: A pillar of Grant’s success lies in his administration skills, which I have detailed further on. Measuring man-days is a key part of this department and is facilitated with the ticket and task system explained above. Grant is happy to report that he has managed to improve the 55 man-day per hectare cost of running this farm, in the beginning, down to 38 currently.

SOIL MANAGEMENT

Poor soils was top of the list of reasons why this farm wouldn’t succeed, according to most. But, by ‘thinking outside of the box’ Grant has managed to beat the odds. His strategy has been two-pronged:

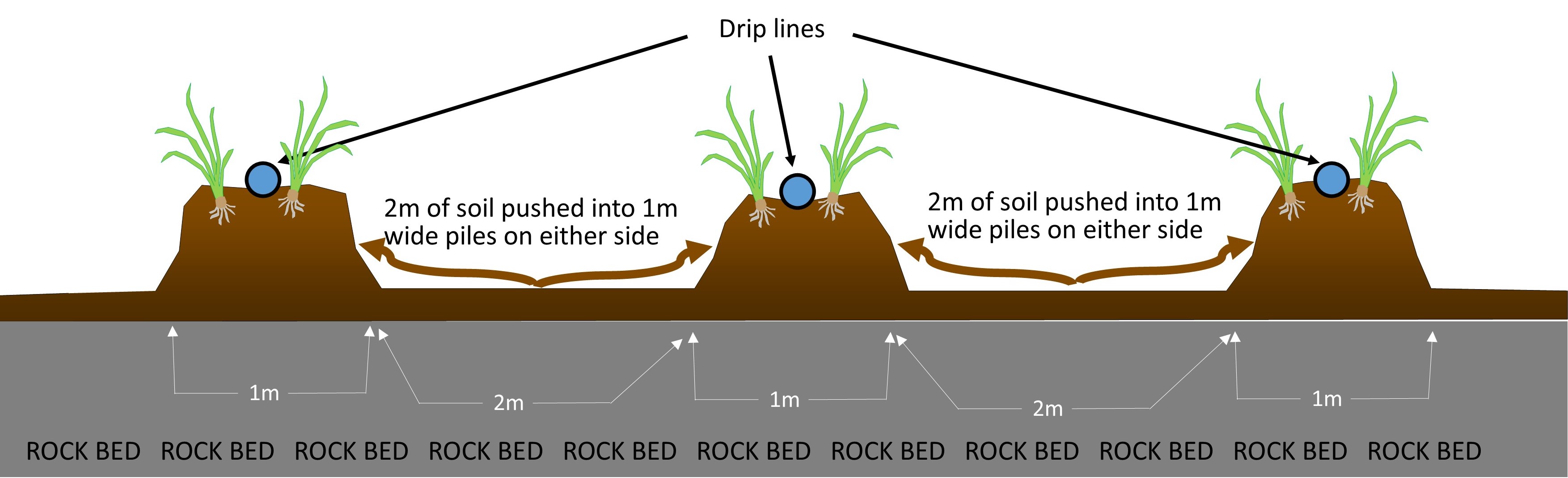

- Use what you have and work hard to improve it. Grant has a thin layer of marginal, clay-free soil atop a rock shelf. That’s why it was deemed unsuitable by the scientists. Because of the lack of clay content, the water runs straight through it and off along the rock below. To deal with this, he builds up a pile of sand to farm in and supplements it with kraal manure (increasing organic and microbial content) and gypsum (correcting the acidity). For those of you like me, who need pictures, here is a graphic:

10 tonnes of kraal manure and 10 tonnes of gysum are added to every hectare during replanting. Grant emphasises that it is important for him to work these supplements into the soil so that they benefit from drip irrigation – the water breathes life into the organisms and microbes in the manure, without which it would be sterile and useless. Grant regards his soils as his bank and this input, as investment. “Shaping it up into piles so that I have enough for the drip irrigation and plant is just logic,” explains Grant. Leaving a 2m gap between each row seems like a lot but it was what was necessary to gather enough soil to farm in. Despite only farming 1 in every 3 metres, Grant averages 125 tonnes per hectare! A farmer worth listening to? I think so …

Kraal manure

- Arable rotation. These poor soils benefit from Grants core philosophy of arable rotation. It is more than diversification and it is more than break cropping, it is what happens when you realise the value for the soil of growing different things. We know the adverse effects of mono-cropping and do break crops fully address those? We know the financial benefits of diversification but do we apply employ it to beef up the bank balance or the soil (which Grant refers to as his bank)? Besides sugarcane, Grant grows litchis, mangoes, citrus, bananas, papinos and veggies. Not all of those are in the ground right now and he is doing trials with macs and, soon, avos. The rotation is continuous and serves to fortify the soils which, in turn, fortify his returns. Grant believes that sugarcane farmers, particularly those in KZN, could benefit from the practice of arable rotation as some of those soils have been supporting cane for over 90 years.

As an aside, for anyone with a finger in the mac pie, look at how Grant is pulling the mac branches open to allow more sunlight into the developing trees …

A spin off benefit Grant insists is related to the arable rotation is the lack of pests or diseases. When I asked how he handles sugarcane monsters like Eldana, he explains that only once has he ever had any pest or disease on the farm and that was one patch of smut in a field of N32 which he simply ploughed out.

Yet another positive spin-off of this regular replanting is that Grant is constantly ahead with the latest varieties. This not only positions him well to be a seedcane supplier but also makes sure that he is growing the most current varieties and benefitting from their scientific modifications.

FERTILISERS AND HERBICIDES

Interestingly, Grant combines these two facets of farming. We’ve heard it before – farmers saying that the presence of certain plants (weeds) indicate a lack of a certain element in the soil so, instead of spraying herbicides, Grant will often supplement with whatever he understands the soil is asking for. Eg: Watergrass indicates a drainage problem, cynodon usually grows where there are heavy, clay soils and pH is too low – the soil requires gypsum. Clovers indicate a lack of calcium. When I asked about lime, Grant shakes his head and explains that that is a “Natal thing”, gypsum is the mineral of choice to correct pH in the north.

Infield water distribution, proper drainage and off-flow management, are all important parts of irrigation design.

Infield water distribution, proper drainage and off-flow management, are all important parts of irrigation design.

Another thing he warns about is using harsh fertilisers continuously, which he says sterilises the soil. He advises that harsh, salt-based fertilisers are alternated with softer, sulphate-based fertilisers for better long-term outcomes. Again, the theme of rotation and adaption comes up and seems to be a common thread throughout this farm: a few years ago, in the severe drought, Grant needed to do something about a few fields that were really struggling. He decided to try a foliar feed and, on the 27th Dec, he ordered liquid urea, made a suitable mix, and fed nitrogen to the cane via their leaves. It proved to be what it needed, justifying his quick and alternate decision. This intuition for what the plant requires in the soil is also guided by soil samples he does with the mango crop. Generally, he uses a 150:30:150-200 fertiliser on the cane, applied in three parts; the first is within two weeks of planting or harvesting. The second is in Winter and the final application comes in Spring. Grant adds that you need to make sure your calcium : magnesium ratios are always correct (5:1). Another element to be monitored carefully is nitrogen, especially approaching harvest; RV (and BRICS in his other crops) is increased when the soils get rid of excess nitrogen. A lower nitrogen level at harvest = higher sugars. You need to monitor your nitrogen uptake curve to time this right.

By changing the spectrum of weeds, the herbicide bill is now down 30% from when he started on the farm, a factor he also attributes to his low tolerance for weeds. “One year’s seed = ten years’ weeds”.

Fertigation underway …

Fertigation underway …

ADMINISTRATION

Grant is a man of numbers. I believe it is a big part of how he manages to exclude ‘noise’ in his business strategizing. Numbers are apolitical, clear and facilitate the conclusion of sound business decisions. The collection of these numbers is daunting for right-brainers like myself but Grant showed me that it needn’t be. I was flabbergasted when he took me through his simple, yet detailed, excel spreadsheets (the actual ones) wherein every single cost on the farm is allocated to a cost centre and every cost centre to a crop, resulting in clear profit /loss totals. The transparency of this man is refreshing and easily derailed me from what he was trying to communicate: you have to apply a value or number to every activity, process or tool so that it can be measured. You use these measurements to assess your situation (are you making money, are you spending too much money – how, where and why) and make decisions for the future (eg: farming crop ‘x’ is not profitable). See – clear and uncluttered! (And there I was, still trying to process the fact that Grant was showing me not only his bottom line, but every line! )

COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

Getting involved is not a guarantee of security or even harmony, but it is one of the ways that we can fulfil a mandate to improve the lives of those around us and try to leave the world a better place. Grant still spends over R500 000 annually on 12 full time guards and a complement of night-time watchmen. His investment in the community around him comes from a personal belief that, as a successful farmer, he can help and therefore, he does. He did this by creating a company, Zelpy1174, that incorporated 19 small scale growers. He guided them to farm along his principles and, because their soils are so much better than his, their results actually surpassed his own. The company still exists, is debt-free and is still doing well. All that was done independently of any industry or government support, justifying Grant’s argument, expounded later on, that there is no need for expensive support structures in the sugar industry.

The surrounding community is obviously Grant’s source of labour and he invests therein by making sure that everyone who works for him has a solid house structure, fully owned by themselves, on their land. He gives them sand from the river and together with cement that they purchase, they make bricks at Lomati with which to build these homes.

The brick plant …

EQUIPMENT

Being a skilled mechanic makes it easier to operate older equipment but Grant insists that you needn’t own equipment at all (as demonstrated by Zelpy’s farming model) and that brand new, expensive tractors every couple of years are nothing more than self-indulgent luxuries.

His equipment operates in a very abrasive, rocky environment, maximising machine wear. It is what it is and he chooses to rather focus on areas he can control. Road maintenance and improved field layouts have reduced operating costs like fuel and repairs.

Grant did buy one small tractor this year but the majority of his machinery is old, yet fully functional.

Grant did buy one small tractor this year but the majority of his machinery is old, yet fully functional.

IRRIGATION

“Of less importance is what type of irrigation system you choose”, says Grant, “more important is that you minimise energy costs and maximise efficiencies of whatever you decide to use.” This can be done by engaging with a good irrigation engineer. Grant explains how Herman Bosua from Bosua and Associates in Barberton has helped him reduce energy consumption and increase irrigation efficiencies: this has been done by reducing friction (larger pipes allow freer flow with less friction) and maximising infield distribution. eg: Grant has a 75kW pump in the river to pump up to his dam. It had about a 6m suction head and he was getting about 320m3/hour. To improve this, he put a submersible in the water to reduce the head and he now gets about 420m3/hour. The next step will be to upgrade the main line, increasing the capacity to 520m3/hour.

Grant explains how the new submersible has helped efficiencies.

Grant explains how the new submersible has helped efficiencies.

Grant works on delivering 10 000 – 15 000 m3 of water onto each hectare every year, on top of the rainfall. He does this by delivering 6mm daily, through drip irrigation, knowing that there will be days when evaporation goes up to 9mm. Grant has chosen drip irrigation because of the water saving (overhead sprinklers would cost him another 1mm every day because of the evaporation associated with this method) but says that there isn’t a bad irrigation system, “You just need to manage what you have well. I ensure my drip system is both effective and cost efficient, for my farm, by placing a drip-line every 3m, with 2 litre emitters, every 600mm. In the Zelpy operation we managed to draw out higher yields with 40% less water, because their soils are far better. The point is that you need to tailor what you have to suit what you farm.”

Irrigation is a 24 hour operation, Christmas Day included. In 20 years, he has never left the farm during this festive season. Being mango and litchi harvest, it’s the busiest time of the year.

The water management plan includes collecting the run-off and reusing it

The water management plan includes collecting the run-off and reusing it

FORESIGHT

Grant is not modest about the prosperity of his enterprise and insists that lucrative opportunities are abundant, even during the drought; when this last drought was intensifying he advised others to invest in seedcane plots because of the demand that would materialise when the drought broke. Following his own advice, he turned those drought years into above average profits when he used 30% of his cane land for N57 seed beds which he sold at a R400/tonne premium.

This foresight extends beyond the farm and includes not only crop diversification but income stream diversification: Grant owns a grocery store and a property portfolio.

HARVESTING

Grant works on a 12,5 month cutting cycle. Not all fields are cut every year and he has a replant of 15-20% annually. All these practices have been developed to get the best out of the resources on this particular farm, with special consideration for the poor soils. The point here is wise management rather than following exactly what Grant does. He would not be doing the same things on a farm that did not have the same resources.

Cutting, loading and hauling are all contracted in. Grant doesn’t feel his cane crop is big enough to warrant the specialist staff or equipment required to harvest and haul the sugar. His preference is for a stable workforce of permanent employees. The week I was on the farm saw 3000 tonnes harvested and hauled to the mill in 4 days. The irrigation pipes were reinstalled 24 hours after the haulage was complete. The efficiencies of hiring harvest specialists appeals to Grant.

A drawback of contractors harvesting is that there is less regard for compaction and there is mechanical damage to the beds. Grant is tolerant to a point, saying that some costs are unavoidable and just need to be factored in. He repairs the fields after the harvesters have moved out.

PLANTING

Very simply, a ridge is pulled through the mound described above. 14 man days per hectare is allocated to cut and plant the seedcane which is then covered with a tractor implement. No fungicides, fertilisers or supplements are planted with the cane. Currently, Grant has a preference for N57 but only plants it in the spring; “It doesn’t do well if planted early in the season,” he explains. Because he is marching his fields out on a 12,5 month cutting cycle, getting this specific timing right is not always possible but he does try to manage the planting with cognisance to the most suitable timing.

GRANT’S VIEWS ON THE FUTURE OF SUGAR

With Grant’s clear ability to rustle up opportunities in any sector, I wondered why he tolerated the sugar industry challenges and continued to farm the crop. He insists that sugar cane has a place in his arable rotation policy and always will. Although he is despondent with the current industry structure, he is hopeful that it will reform.

Grant advocates deregulation of the sugar industry and sees this as a solution to many of the challenges faced now. Currently all farmers pay a levy to SASA (one mandatory levy, going into one pot) and in return for that they get a price for their cane (everyone gets the same price) and SASRI support (extension officer, varieties). Grant’s view is that both parts of this arrangement can be improved through deregulation; the price farmers get for their cane could be higher if it wasn’t pulled down by the sales to the industrial markets (these are at lower prices). Instead the mills could develop and market their own strong, independent brands more aggressively and realise better prices. Grant feels that the SA Canegrowers support currently on offer is over-priced. To illustrate his point he explains that Komati farmers paid R10,4 million in levies for the past season. That is R4 per tonne. The area SACG team (comprising 4 people) carries a cost of R1 per tonne. “What happens to the other R3 per tonne?” is Grant’s big question. I verified that there is indeed an extension officer covering the region but Grant says it’s a recent appointment and one that was vacant for 19 years. He draws my attention to the fact that Komati is the most productive sugar growing region and says “We’ve managed pretty well without it.”

Grant does acknowledge that support structures do hold value in terms of research and product marketing, what he’s questioning is the price the sugar industry is currently paying for the services they receive. Deregulation would not eliminate support but it would serve to slough off a lot of the industry fat and streamline the sector into a more economically viable situation.

Other industries he’s seen deregulate and prosper are banana, mango and citrus. In this scenario, you chose whom to sell your harvest to and still get many of the same support services in terms of research and crop support – I saw this in action when I was researching the article on diversification into macadamias. In a regulated environment, some players are protected at the expense of others and this brings another point to Grant’s argument – he feels that the sugar industry is currently oversubscribed, exacerbated by the fact that sugar is an easy crop to farm. When deregulated, there would be casualties but that would be healthy fat-shedding – in Grant’s opinion this would be about 30% of the industry. When looking at it from his perspective, it’s difficult to disagree.

“At the end of the day all I am promoting are proper business strategies over pure politics on the agricultural side of the industry. Thankfully, to this point, the millers have had the insight required to keep the industry alive,” explains Grant.

CONSULTANCY

Grant is one of the most open, honest men I have met. He floored me with his candour and transparency. Added to that is his genuine interest in everyone’s success so, while his manner may be abrasive and controversial, from his perspective, what he’s saying is sound. If you’d like to engage with him further, he has a consultancy business and was happy for me to disclose his contact details: Grant Taylor, Cell: 083 441 1671, Email: grant@taylor.co.za

Thank you, Grant, for sharing your practices, knowledge, advice and views. It’s now up to us to take that and see how it can be applied to our own enterprises.