Our last article focused on Water Management and explained that, as the mac trees in our orchards are only about 2 generations down from their wild grandparents, we are best advised to work WITH them. By looking closely at the trees, we will learn what it is they need to produce a good crop. I am sure that this concept is not isolated to water management, so let’s get into “Canopy Management” and see what we find there.

When it comes to pruning, there’s a name that has come up a few times – Alwyn du Preez. I am sure most of you know (of) him. He has established himself as a valuable, broadly-qualified consultant whose pruning advice is particularly sought after. I was honoured to meet with him on my country trip and much of this story is built on the knowledge he imparted. Another name I have encountered, in an extremely positive light, is Sarah-Jane Stewart. She is a technical advisor with Mayo Macs who has had first-hand experience in her own orchards. I tracked her down during our lock-down (virtually, not physically) and she sent me two very helpful publications that they produce – one on training young orchards and one on pruning older orchards. (Thankfully) the experts all agree on most things and I have interwoven the wisdom from both to create this broad article. Sarah-Jane did have some foundational input that would be helpful from the start: “Macadamias respond so well to pruning yet it’s a vastly neglected task. More so when the harvest finishes late and the next seasons flowers are pushing through, we are so nervous to cut away potential crop. Focus on the bigger picture and know you have to break eggs in order to make omelettes. If trees are too tall, reduce their height; if canopy is to dense open up a window; if branches are too low, skirt them. There really are just a few simple practices to pruning.

Take the time to prune a few trees along with the people doing the job. You will soon get the idea of the best tools needed, how many trees to prune per task and which of your staff have an eye for pruning, as it is an art that not all people can master. Most importantly, be realistic to your farm setup, don’t worry about what the neighbour is doing on his farm as it is different to yours, each farm is unique. If your trees are grossly overgrown it may take you 3 seasons to bring them back to size without dropping production too much.

However, like most things in life, if you train a tree correctly from a young age it will be easier to manage as an adult. My advice is start young, develop the framework and complexity of the tree and pruning later becomes the simple removal of limbs.”

Alwyn did emphasise that each mac orchard is unique – The farmers that manage them are individuals, with their own set of characteristics, some orchards have been pruned harshly, some haven’t seen the shears for way too many years, some are planted densely and some have runways. And then there are all the different cultivars and their unique growth habits. All these differences almost make a generalised guide impossible, but we have ‘impossible’ for breakfast … so here goes …

Back to our wild macadamia tree. It’s a big beast. A mac tree can extend its radius by an average of 30-40cm per year. Left unpruned it will grow wildly. It will continue getting bigger and bigger for many decades. It will bear predominantly on mature wood that is not too thick. We have a large factory with a large production. The problems only start when we take this big beast and put it in a confined space, like an orchard, right next to an equally big beast who also needs sunlight to run its factory. Add a pest problem and a productivity goal and you are going to need to get involved. If your trees have gotten so big that they no longer get enough sunlight and you cannot get a tractor in there to spray, you start going out of business. So, pruning is an essential activity in managing a mac orchard towards optimal productivity.

REASONS FOR PRUNING:

- Equipment access (for spraying, maintaining, fertilising etc)

- Productivity – the tree needs fresh bearing wood inside the shaded canopy

- Sunlight access

- Wind survival (in young trees)

- Airflow (to minimise fungal risk)

- Maximise spray efficacy for pest and disease control

When it comes to equipment accessibility, you need to plan from the very beginning; when planting. Orchard spacing has been through a broad range of options and seems to be settling on 8m x 4m as an industry standard. This is variable when it comes to specific farmer preferences and cultivar growth habits. Small trees, like A16s could be planted more densely but some of the old Hawaiian cultivars like 344, 816 and 741 tend to grow quite vegetatively when pruned and need a bit more space. Left to grow naturally, the average mac tree will grow upward, with more than one main stem, and form an oval shape.

PRUNING FOR TRACTOR ACCESS:

If rows are planted 8m apart and a tractor needs a minimum of 2m, you are left with 3m of ‘factory’ on either side of a tree trunk.

PRUNING FOR SUNLIGHT MAXIMISATION AND SPRAY EFFICACY

Oval trees inhibit both sunlight penetration and spray efficacy. A cone-shaped tree is going to maximise the amount of sunlight because it reduces the shade thrown both on its own lower branches and on neighbouring trees.

In order to protect bees and other beneficial insects, we should spray pesticides at night. (Alwyn prefers not to spray at all during flower-time and if it is absolutely essential, then only to use a low-residual spray, at night).

During the night, pests tend to retreat to protected inner branches, higher up in the tree canopy. A cone-shaped tree does not restrict pesticide penetration like an oval one would.

So, getting the trees into a conical shape should be fairly simple with an angled hedger (all-cut pruner), right? Right. But, oh so wrong, says Alwyn. And he backs this up with a few points:

- Hedgers make many small cuts, all on the outside. Every cut stimulates vegetative growth. Many cuts = extensive vegetative growth. If the tree is putting energy into excessive vegetative growth, it won’t have enough for the reproductive growth a commercial farmer needs.

- The extensive vegetative growth also creates a ‘green curtain’ that will shield the inside of the tree from life-giving sunlight and thereby creates a great big unproductive vacuum in the centre of the tree.

- Hedgers continuously “shave off” the new growth. As discussed, macadamias bear on mature wood but not thick structural wood. If you continue hedging, you will, overtime, end up with very little productive wood.

- Hedgers that cut at an angle of 45° angle cut into numerous branches (thick mature wood) at the top of the tree and create a lot of regrowth in that area which will need to be controlled later, BY HAND – this is very labour intensive.

for general pruning. It can be used to open up the rows at a straight horizontal angle if the grower use it alternatively on cultivars like Beaumont, but that is it.

So, for general pruning, hedgers do not get the expert’s approval. (Alwyn does mention that there are select circumstances where this equipment may help e.g.: occasional opening of the rows or in alternate maintenance of Beaumonts).

Now what? Humbly, Alwyn admits that we are all still learning but, based on what he knows about mac trees now, he prefers to make FEWER BUT BIGGER CUTS each year. If you cut too much in one season you will send the tree into a vegetative state and it won’t produce a nut the following season. Sarah-Jane contributed her personal experience in this regard: “100% agreed, I have used this all-cut machine in an orchard to supposedly save time and get the tree into conical shape. Fortunately, we only used it on the left side of each line and not both sides as the results were no flowers at all on the hedged side, the following spring, only a mass of vegetative regrowth ☹”

So Alwyn carefully plans ONE major cut per season, per tree, rather than leaving it a few seasons and then doing a major prune that involves many major cuts. He starts by attending to one ‘shoulder’ per year with the goal of creating a cone-shaped tree in about 3 years.

If trees have been allowed to grow too tall then the third year can be used to top the central leader. By then there would be some new productive branches in the gaps you created in previous years, lower down, that will compensate for the cut in production on top.

How tall is too tall? Generally, 6m is manageable for spraying equipment. But Alwyn would be happy with 7m to 8m IF the top branches are sparse and the sprayers can reach there. But, if you have a dense tree canopy in that top 2m (i.e.: from 6m to 8m) which is not easily accessible to the sprayers, then it would be best to remove it. Generally, the rule of proportion to follow is that your tree height is 80% of your row spacing. So, if you have planted at 8m apart then 8m x 80% = 6,4m, rounded down to 6m.

Do not make table top cuts. Alwyn strongly advises against cutting off all the branches, exceeding your desired height, in one year, even if your height is a problem. That would be called table topping and creates more challenges down the line as all the energy going up that “mainline” will manifest in vegetative growth.

Instead, you should leave a dominant leader that would suppress the competitive growth.

The Mayo Macs manual adds that you should make sure that these cuts are ‘flush’ cuts (right up against the trunk) – that will minimize regrowth and therefore reduce removal at a later stage.

What if there are more than 3 branches exceeding the ideal height? Regardless of how many there are, the programme should still be planned over 3 years. In the illustration above, we have assumed that there are 3 branches and that we will address one of those per year. If you have 4, 5 or 6 then you still address this over 3 years i.e.: in year 1, take out one third of the wood – if there are 6 branches, then that is 2. If there are 4 then still try to apportion it into 3 e.g.: take out a thicker one and the thinnest one in year 1. Always be careful not to cut too much because a macadamia is wired to respond to cuts with vegetative vigour, which will reduce the productive investment in nuts made by the tree.

Another key point to remember is that a mac tree generates a lot of energy that it has to spend. Normally, that energy creates nuts BUT, if nuts cannot be produced (e.g.: a flower disease or over-pruning of bearing wood) then it will spend that energy vegetatively. We are in the business of nuts so we need to always remember to direct the tree’s energy into this resource. The more nuts you can set on a tree, the less it will grow (and the less pruning will be required). Alwyn always has to be careful that he does not send his farmers’ trees into vegetative mode therefore the pruning must be subtle and carefully thought out. To be safe, Alwyn tries to limit his cutting to 25% of the tree in one go.

He explains that, before cutting, you need to know what the purpose of that cut is. Consider what a branch is? Is it bearing wood or is it an essential part of the tree’s structure i.e.: all branches are passage ways (pipes) for water and nutrition, like an irrigation system. When you take one ‘lateral’ or ‘mainline’ out, think carefully about what that does for your overall system.

- Is the branch a mainline, although not bearing, it is supplying laterals that are bearing.

- Is it bearing wood –consider the loss in production before cutting.

- Gradual shaping is best because it allows you to monitor how the tree is responding to the cuts. Corrective action or a deviation from the original plan is always possible.

- Cuts stimulate vegetative growth so fewer cuts = less vegetative growth.

- Vegetative growth steals from reproductive growth (nuts) AND

- It prevents sunlight getting ‘inside’ the tree, creating dead space.

Deciding which wood to remove: Alwyn suggests removing competing central leaders first.

- This will help create the cone-shape.

- When a branch gets too thick, it stops bearing (may be one or two flowers but essentially, the show is over) so these big branches would be the ones to take out, UNLESS it is the main line for your tree structure or taking nutrition to other branches that you want to keep.

NB: All pruning takes out some bearing wood in the short term (following season) but generates bearing wood in the long term (2 years) where we want it. It is important to manage harvest expectations accordingly.

Second phase of pruning: when removing a branch, consider carefully WHERE you cut it off as managing the regrowth is the second part of your pruning process. If you cut it off flush with the trunk, there will be minimal regrowth as there is minimal sunlight. “Water shoots” from the lower branches will quickly fill this space with unproductive wood. NB: Vertical branches are not good bearing wood; only horizontal ones bear heavily. If you leave a short stump on the pruned branch, one that extends into some sunlight, it will produce multiple new branches and you can then select a few (3, maybe 4) horizontal ones to groom into new bearing wood. You make this selection when the new shoots are pencil thickness. When making the selection, keep in mind that, in a few years’ time, these branches will be as thick as your arm.

Neglecting to come back and manage the pruning process into phase 2 could make an excellent first cut useless or even harmful. If you only go back two years later, you may find a hell of a mess. Controlling that regrowth timeously is of utmost importance. Selecting the right regrowth to keep is also important. From the ‘bush’ of shoots, select two or three horizontal laterals. If you pruned in winter, and go back the following summer and instead of breaking them off (cutting) and inviting more regrowth, you can break them OUT, by hand with just a pair of gloves, and they won’t regrow. Coming in too soon can also be harmful though – as all the shoots are very soft and delicate. Labourers may unintentionally damage valuable laterals and you are left with a bare stump again. Timing is key in pruning.

What about skirting?

Alwyn usually recommends a skirt that is knee-height but that is dependent on what the farmer is comfortable with. He will supply the labourer with a stick that is the correct height and he takes a pair of lobbing secateurs and cuts off the portion of the branch that hangs below the height of the stick. When addressing this lower part of the tree, it is important that the branches are NOT cut off at the trunk or even on a stump, like was recommended for the higher branches. There will be minimal regrowth from a skirt branch because of the minimal sunlight at this point. The point on the branch that intersects with the height of the stick is where it should be cut.

Cultivar specific advice:

Beaumont is apparently a nice one to manage as it tends to produce lateral branches naturally, when young. 816 likes to make multiple central leaders and grow very upright and I can tell that Alwyn has struggled with this one quite a bit – he calls it a “deurmekaar” tree and explains that it struggles to make horizontal side branches; it just wants to grow up with multiple leaders. It takes effort, from a young age, to train it to make horizontal laterals lower down. Sarah-Jane adds; “816 and 344 make very narrow crotch angles. If these are not manipulated early, it also leads to branches snapping in the wind later.”

Mechanical manipulation (bending): Alwyn is not a fan of this strategy as he feels he can train a tree with secateurs far easier than with ropes and ties etc. He says that wind puts these manipulated trees at risk of breaking/splitting. He suggests that you rather remove the competing leaders so that the tree cannot be torn apart by the high winds. Making these major cuts when it is a young tree is so much easier than letting it get out of shape and having to do it to an older, bearing tree. I was also interested to learn that, as soon as a branch is bent below the horizontal, it produces water-shoots.

From young: Undeniably, pruning is most important when a tree is young. Alwyn discourages staking in the Lowveld. Sarah-Jane explained that it is often necessary in the coastal region where winds can be excessive. Alwyn prefers to cut a sapling down to about 50cm to 70cm, depending on:

- how many leaves are below that cut – there should be at least 3 leaf whorls below a cut on a young tree

- what cultivar it is – A4s, in particular, split easily in high winds

- how windy the orchard is.

(NB: Other consultants prefer not to cut lower than 60 to 80cm; the exact height is a matter of personal preference)

These early cuts should not be made in winter, when the tree has little chance of a flush. Usually, six weeks after cutting, the tree will pop with new buds, unless it is winter. Similarly, it shouldn’t be too hot otherwise any new growth will burn. Alwyn restricts young tree trimming to the start of the rainy season (end October, early November), when it isn’t too hot, and regrowth is certainly possible.

After this first cut, the tree will generate its leaders and you will need to select a central leader by cutting out the competitors. Doing this will result in a young tree better able to withstand strong winds and reduce the need to shape in years to come. I wondered why we bother cutting the single stem right in the beginning, if we, once again want a single stem later on … Alwyn explains that the stem needs to be thickened up in the beginning and the only way to do that is to crop it back initially. Ratio of canopy to stem thickness tells you whether it is going to withstand wind. If your ratios are off, you should prune before the windy season starts.

Sarah-Jane brings some valuable KZN-specific input at this point: “On the KZN coast, farmers still use stakes as we have consistent winds, unlike Mpumalanga (Alwyn’s turf) who has a lot less wind. Regrowth, in these high-wind belts, is not as vigorous because the wind burns off new growth, therefore farmers prune less in the first year to compensate for wind damage to juvenile growth.”

PRUNING IN THE EARLY YEARS SAVES YOU PRUNING LATER ON

Alwyn explains that he would come back to a young tree about 4 times (over four years) and then, when it comes into bearing, it will seldom require upkeep. Sarah-Jane concurs: ”It is vital that new growers bear this in mind. When the trees are young and not producing the workload is less than bearing trees, so spend the time, while you have it, getting the shape and framework correct. On dryland orchards one can reduce the pruning to 2-3 times, as growth is slower.”

| Year One | · Top the tree |

| Year Two | · Manage regrowth

· Select central leader |

| Year Three | · Manage regrowth

· Shape (conical) · Ensure that the ratio of stem to canopy size is correct (not too heavy) |

| Year Four | · Thin out the canopy and make sure there is enough sunlight penetration. |

Alwyn does appreciate that there are many tasks that compete for a farmer’s attention though. Pruning of small trees often gets left behind in favour of things like weed and pest management, production and harvesting which all seem much more important at the time.

Timing the prune:

Don’t prune too early (Feb, March, April) as this will stimulate growth before winter. By cutting a little closer to winter (May) you will divert the energy into nut production rather than vegetative production. The timing of vegetative flushing is important because immature leafy flushes, during late autumn and early winter, inhibit raceme production. The tree has finite energy reserves and it has to decide what it must invest in, in the next season – buds, branches, flowers … timing your cuts correctly gives the tree guidance on where the energy should go. Cutting it back too early induces a decision to invest in regrowth (leaves). Alwyn only starts pruning in May, no matter when the harvest ends. He suggests his farmers go fishing if they really cannot think of anything else to do besides pruning early. This got us into the whole discussion on withholding food and water from a mac tree with the aim of stressing it into producing more flowers. Alwyn explains that these trees are evergreen, meaning that they photosynthesise all year. If you withdraw investments in that tree, you reduce the energy it has to perform all the functions it would normally. It has to start making choices. Withholding nutrition may well result in a heavy flowering but then the tree has less energy to set and develop nuts. He advises against withholding anything. Rather give the tree what it needs, when it needs, and minimise your interference. Always stay cognisant of when it is making investments in which activities and guide it towards nut set and development, for obvious reasons.

Don’t prune too late: Pruning into flower time is only a problem in that the falling branches can damage flowers. Alwyn said that most farmers do not like to see how many flowers they cut off and then tend to cut less. Trees in full flower also give the impression that the canopy is denser – this can be deceiving and lead to poor pruning decisions.

As far as withholding nutrition, Alwyn doesn’t advise it – he notes that the orchard will require less food and water in winter as photosynthesis is lower but that is not withholding – that is catering for the reduced needs of the plants.

As always, the conversation meandered and touched on few other interesting points. Although not completely relevant to an article on pruning, I couldn’t resist sharing the information.

Harvest: Alwyn also advises to harvest as soon as the nuts are ready so that you remove the energy-sapping nuts off the tree and allow it to recover and have resources for the next season. Alwyn explains how some avo farmers are leaving their fruit on their trees to get the benefit of the higher late-season prices – this has resulted in poor crops the following season. From this example, it becomes clear how alternate bearing could be attributed more to carbohydrate management practices rather than cultivar characteristics. In some cases, harvesting early also has the benefit of inducing earlier flowering which is great in order to avoid the hot, dry, stressful periods.

The Future: As we know, macs are still essentially ‘wild’ – they have large, superior, highly efficient root systems. Essentially, they are V8 engines wired to produce a large tree. More vegetation = fewer nuts (proportionately). In more ‘domesticated’ crops, humans have managed to redivert that power, from stimulating a tree vegetatively to stimulating its fruit production. They have done this by developing a dwarf root stock. These are available for most other fruit crops – citrus, plums, apples etc. When you graft onto this smaller root stock, the result is a smaller tree that is still very productive. The tree focuses on reproducing (fruit) rather than growing vegetatively.

At the moment, there is no macadamia dwarf root stock, so we have to manage the output of these V8 engines in an orchard environment. We need to do this as cleverly as possible. Taming the wild beast is not going to be simple and careful consideration should be given to every strategy. By pruning we are just doing the best we can until a dwarf root stock is developed that will make our attempts at manipulation a little more meaningful.

Thank you, Alwyn, for your time, wisdom and generosity in sharing.

Here are a few additional titbits I have been saving for this pruning article:

Real examples: Pruning was pivotal for one farmer in particular who was recording increasing unsound kernel to the point where he was losing unacceptably (R2,7 million in a season). He identified a few contributing factors but top of this list (also the cheapest & easiest to remedy) was overgrown orchards. I am told that his trees were excessively tall. In 2018 he embarked on a strategy to address his unacceptable losses:

- Prune trees to 6 m height

- Investment in two more sprayers to get around the orchards more quickly

- Spraying at night. Because of night spraying, he added trackers onto his tractors which improved management of this activity

- Installed a weather station (to know when not to spray).

Here is a graphic representation of the impact these changes had:

(White River Study supplied by Green Farms Nut Company)

GFNC kindly supplied this information to support the industry in finding solutions to unsound kernel rates; effective pruning is probably the main solution to this challenge.

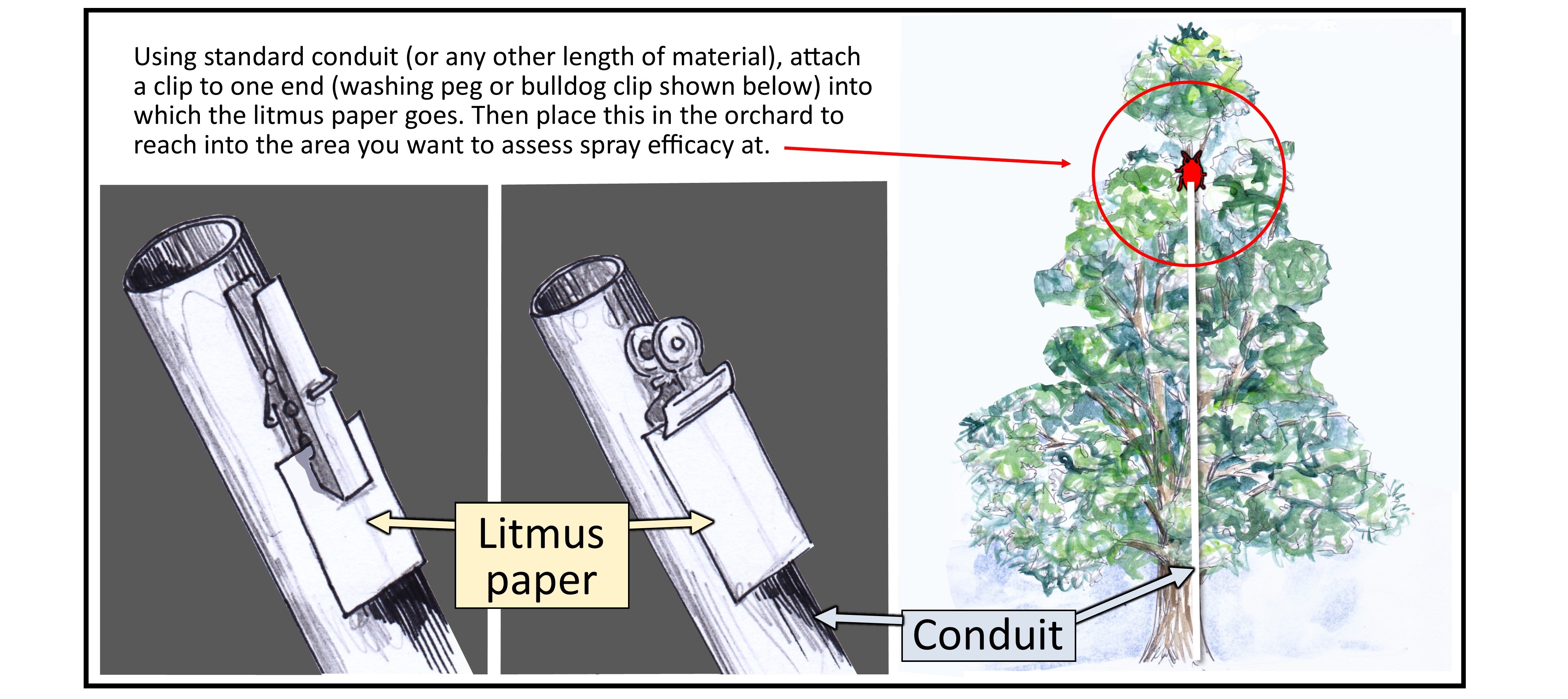

Another super-simple but amazingly effective tip I picked up whilst on Maluma, Elsie & Stoffel Joubert’s farm in Limpopo, was on how to evaluate whether your spray is reaching the stink bug hangouts in the higher, sheltered areas of the trees … they use a piece of piping, cut to the height they want to test at. To the one end they attach a clip, and clip a piece of litmus paper in that. They then put these ‘poles’ randomly, in the orchard (you can just lean them against a tree trunk and secure with a string or wire), before the sprayers go out. After the spray they take them down and evaluate whether the spray reached the litmus paper (and therefore the section of the tree that was worrying them). When feedback is given to the staff who are responsible for this activity, having the results (proof) helps land the lesson.

The reason you use litmus paper is because it will change colour, if it gets wet, and hold the colour change when it dries so you can come back a few hours later and still get results as to whether the spray reached the part of the tree you wanted it to.

To wrap up this story, I’d like to bring you counsel from many of the top farmers in Limpopo. As the industry there is our country’s most mature, they have walked a journey that the majority of us haven’t. A failure to prune properly will create environments for pests to shelter and, before you know it, they will be out of control, consuming your nuts, your energy, your money and your sanity. They implore mac farmers to not repeat the mistakes they made: PRUNE PROPERLY.

Sincere thanks to Alwyn du Preez from Macadamia Technical Consulting, Sarah-Jane Stewart from Mayo Macs, Barry Christie from GFNC and Elsje Joubert from Maluma Boerdery.

The next article (publishing mid-June) will cover “the beginning …” bringing you insights into everything important before you even plant your mac trees. Nurseries, land prep etc.